Chapter 44 Aneurysms of the Peripheral Arteries

Nonmycotic Peripheral Aneurysms

Incidence and Cause

Overall, the most common cause of nonmycotic peripheral aneurysms is atherosclerosis; however, depending on location, this is not true for all peripheral aneurysms. In general, all peripheral aneurysms can be considered rare. In descending order, the relative frequency of these aneurysms is popliteal, femoral, subclavian or axillary, and carotid. Reports on distal aneurysms involving the brachial, radial, ulnar, deep femoral, and tibial or peroneal arteries are limited to small series or case reports. Although true aneurysms have been reported in these areas,1,2 for the most part, forearm, hand, tibial, and peroneal aneurysms are secondary to trauma or are mycotic in origin.3

Extracranial Carotid Artery Aneurysms

The rarity of extracranial carotid aneurysms is demonstrated by numerous reports of institutional experience with aneurysm patients. Of 2300 aneurysms reported from Baylor University, only 7 were extracranial carotid aneurysms.4 In 30 years at Johns Hopkins, only 12 such aneurysms were seen.5 Only 8 carotid aneurysms were noted by Houser and Baker after obtaining 5000 cerebral arteriograms.6 The largest single series of patients with true extracranial carotid aneurysms was reported by McCollum and coworkers,7 who saw 37 such aneurysms over a 21-year period. Zhang and associates8 reported 66 extracranial carotid aneurysms, 28 of which were true, nonmycotic aneurysms.

Currently, the common carotid artery is affected most often, followed closely by the internal carotid artery. The external carotid artery is rarely involved.9

The most common cause of extracranial carotid aneurysms is atherosclerosis. These aneurysms tend to be fusiform and are almost always associated with arterial hypertension. Most of the patients also have evidence of generalized atherosclerosis.9 Another cause of carotid aneurysm is trauma, both blunt and penetrating.10 False aneurysms of the carotid artery have occurred after carotid endarterectomy and carotid artery dissections.11 Rarer causes include cystic medial necrosis, Marfan syndrome, fibromuscular dysplasia, medial arteriopathy, granulomatous disease, radiation, and congenital defects.10 El-Sabrout reviewed the literature from 1950 through 1995 and found that of 392 carotid aneurysms, reported etiology was as follows: 40% atherosclerotic, 21% pseudoaneurysm, 14% trauma, 12% dissection, 8% fibromuscular disease, 2% infection, and 3% other.12

Subclavian and Axillary Artery Aneurysms

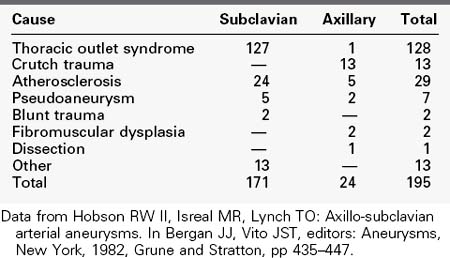

Aneurysms of the subclavian and axillary arteries are also rare. In 1982, Hobson and colleagues reviewed the literature on the subject and found only 195 aneurysms in these locations13; these account for only 1% of all peripheral aneurysms. Of the 195 cases, 88% involved the subclavian artery. Subclavian and axillary aneurysms are rarely due to atherosclerosis, with this cause accounting for only 15% of the aneurysms. Thoracic outlet syndrome is responsible for the majority of subclavian artery aneurysms (74%), whereas crutch trauma accounts for most axillary artery aneurysms (54%). Other more rare causes have also been reported (Table 44-1).

Forearm and Hand Aneurysms

True aneurysms in the forearm and hand are extremely rare. During a 10-year period, only 10 such patients were treated at the University of Chicago.2 Half of the true aneurysms in these areas are associated with occupational or recreational trauma. Most forearm and hand aneurysms are false aneurysms secondary to penetrating trauma3; most true aneurysms in these locations are secondary to blunt trauma.14

Femoral and Popliteal Artery Aneurysms

Aside from trauma and rare degenerative and congenital disorders, femoral and popliteal aneurysms are almost exclusively atherosclerotic in origin.15,16 Together, these two types of aneurysms account for more than 90% of peripheral aneurysms.17 Femoral aneurysms may involve the common femoral artery in the groin, but occasionally these aneurysms are limited to the superficial femoral artery. These latter lesions are often seen in patients with arteriomegaly or aneurysmosis.

Dent and colleagues showed an association between popliteal and femoral aneurysms and other aneurysms of atherosclerotic origin.18 Most commonly, these associated aneurysms are located in the aortoiliac vessels, but more rarely they involve the renal, splanchnic, and brachiocephalic vessels. Among patients with at least one peripheral aneurysm, 83% had multiple aneurysms. Among patients with a common femoral aneurysm, 95% had a second aneurysm, 92% had an aortoiliac aneurysm, and 59% had bilateral femoral aneurysms. Among patients with a popliteal aneurysm, 78% had a second aneurysm, 64% had an aortoiliac aneurysm, and 47% had bilateral popliteal artery aneurysms. Conversely, in a more recent study, the Michigan group has also shown that the incidence of femoral and popliteal aneurysms in men with abdominal aortic aneurysms is 14% (0% in women).19 Of further importance is that most of the femoral and popliteal artery aneurysms in their series were undetectable by physical examination, therefore underlining the need for ultrasound screening for femoral and popliteal aneurysms in men with abdominal aortic aneurysms. Profunda femoris aneurysms have a 75% incidence of synchronous aneurysms.1 Patients with peripheral aneurysms are at high risk for the development of future peripheral aneurysms. Dawson showed that in patients with a popliteal artery aneurysm, new peripheral aneurysms were found in 32% of these patients after 5 years and in 49% of these patients after 10 years.20

Natural History

Extracranial Carotid Artery Aneurysms

Central neurologic events are common in these patients. Rhodes and coauthors reported that 13 of the 19 patients with carotid aneurysms reported in the University of Michigan series had amaurosis fugax, transient ischemic attacks, stroke, or vague neurologic symptoms such as dizziness.9 Most of these symptoms are thought to be secondary to embolization. Cranial nerve compression leads to local neurologic dysfunction and can include facial pain (cranial nerve V), oculomotor palsies (cranial nerve VI), auricular pain (cranial nerve IX), and hoarseness (cranial nerve X). Horner syndrome can also occur from compression of the sympathetic chain. As cervical carotid aneurysms enlarge, they can cause dysphagia, cranial nerve compression, and pain. Hemorrhage has also been seen as a complication of these aneurysms; however, rupture is uncommon.

Subclavian and Axillary Artery Aneurysms

Only 10% of patients with known subclavian or axillary aneurysms are asymptomatic.13 Good natural history studies are not available, probably because of the small number of patients with this problem. Because 90% of patients are symptomatic at the time of presentation, the likelihood of complications eventually occurring in asymptomatic aneurysms appears to be great. The primary complication seen with subclavian and axillary aneurysms is embolization (68%).13 Thrombosis and rupture are rare but have been reported.13,21

Forearm and Hand Aneurysms

The most common presenting signs and symptoms of aneurysms in the forearm and hand are mass and pain. Distal embolization occurs in approximately one third of these patients.2

Femoral and Popliteal Artery Aneurysms

The natural history of unoperated femoral and popliteal aneurysms shows a high incidence of thromboembolic events. Tolstedt and associates reported a 43% rate of thrombosis in conservatively managed femoral aneurysms,22 and in Cutler and Darling’s series,23 47% exhibited major complications. In a study of popliteal aneurysms by Szilagyi and colleagues,15 only 32% of those managed conservatively remained without complications at 5 years. Vermilion and colleagues16 studied 26 popliteal aneurysms for an average of 3 years and demonstrated that 31% of patients suffered limb-threatening complications, with 2 patients requiring major amputation and 2 patients left with rest pain.16 Rupture of femoral or popliteal aneurysms has been reported rarely. Deep femoral aneurysms are particularly prone to rupture, with rates of 13% to 45% being reported.1 Popliteal aneurysms rupture, on occasion, into the popliteal vein.24 Less catastrophic complications include pain secondary to tibial nerve compression and popliteal vein thrombosis secondary to popliteal vein compression.

Diagnosis

Subclavian and Axillary Artery Aneurysms

The most common presenting signs and symptoms of subclavian and axillary aneurysms are secondary to distal embolization (68%; Table 44-2). Other signs and symptoms include tissue loss, claudication, pain, and evidence of brachial plexus compression. When the aneurysm is secondary to thoracic outlet syndrome, it often cannot be palpated. Aneurysms secondary to atherosclerosis tend to be larger and are palpable in two thirds of patients at the time of presentation.21 A bruit may be present in the subclavian fossa or in the axilla. Small, punctate, cyanotic lesions affecting the fingers and palm that are painful and occur suddenly are often present as a result of distal embolization. Rarely, embolization causes large axial artery occlusion. This event usually requires immediate embolectomy, but can lead to claudication if the initial ischemia does not precipitate the need for immediate medical attention. With chronic small embolization, the distal radial and ulnar pulses might not be palpable owing to buildup of embolic material. Repeated embolization may be associated with distal digital ulceration or tissue loss and severe pain. Many patients show vague shoulder pain on presentation. Rupture produces severe shoulder pain radiating into the upper arm and lower neck.

TABLE 44-2 Clinical Findings in Subclavian and Axillary Artery Aneurysms

| Finding | Number | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| Asymptomatic | 20 | 10 |

| Claudication | 9 | 5 |

| Pain | 36 | 18 |

| Brachial plexus palsy | 24 | 12 |

| Tissue loss | 20 | 10 |

| Embolization | 136 | 68 |

When all types of subclavian and axillary aneurysms are considered, only 16% can be palpated.13 Duplex ultrasound is useful to diagnose subclavian and axillary artery aneurysms, but the bony cage of the thoracic outlet may preclude adequate insonation of proximal subclavian artery aneurysms. CT scanning can also demonstrate subclavian and axillary aneurysms. However, because in most cases the diagnosis should be suggested on the basis of history and physical examination, arteriography is the most useful test because it is also needed for proper planning of the operative procedure.

Femoral and Popliteal Artery Aneurysms

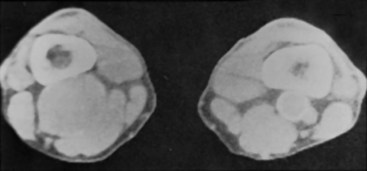

The diagnosis of femoral and popliteal aneurysms is often made by palpation because of their superficial nature. Popliteal aneurysms are suspected in any patient in whom the popliteal pulse is widened and easily felt. Diwan and associates,19 however, found that most femoral and popliteal aneurysms were not detected by physical examination and suggested the routine use of ultrasonography to look for femoral and popliteal aneurysms in men with aortic aneurysms. Femoral and popliteal aneurysms should be considered in any patient with an acute arterial occlusion in the leg or with embolic disease affecting the foot and lower leg. Many popliteal aneurysms are calcified and can be detected by plain radiographs of the popliteal fossa. Both femoral and popliteal aneurysms are easily diagnosed by ultrasonography. CT scanning is particularly accurate in making the diagnosis and is helpful in planning endovascular repair (Figure 44-1). Despite the presence of mural thrombus, arteriography usually confirms the diagnosis and may be necessary for proper operative planning. The status of the runoff vessels visualized arteriographically is particularly important for patients with popliteal aneurysms, because there is a direct correlation to early and late graft patency after repair.25

Indications for Aneurysm Repair

Extracranial Carotid Artery Aneurysms

The indication for operation in a patient with a cervical carotid artery aneurysm is usually the presence of the aneurysm. Because patients with this condition are rarely seen when asymptomatic, most patients are treated for symptomatic relief or for prevention of recurrent symptoms. The high incidence of cranial nerve compression and central nervous system events in untreated patients (68%)9 justifies treatment for asymptomatic carotid aneurysms as well. This finding is common in nearly all reported studies, and the point is not a controversial one.26–28

Subclavian and Axillary Artery Aneurysms

Generally, the presence of a subclavian or axillary aneurysm is an indication for repair. The natural history suggests that these lesions are both life threatening and limb threatening.21 As is the case with carotid aneurysms, most patients are symptomatic at the time of presentation and have clear indications for intervention. Some controversy exists regarding the small, fusiform, post-stenotic subclavian dilatation often seen with thoracic outlet compression of the subclavian artery. The natural history of this lesion, if not resected at the time of thoracic outlet decompression, is not well established. In the four patients with subclavian artery aneurysms who had only thoracic outlet decompression, no subsequent thromboembolic events occurred during follow-up.21

Femoral and Popliteal Artery Aneurysms

Dawson and colleagues20 compared operative and nonoperative approaches to 71 popliteal artery aneurysms. Thromboembolic complications developed in 57% of unoperated asymptomatic popliteal aneurysms over a mean follow-up period of 5 years. In aneurysms studied for a full 5 years, the complication rate was 74%. In comparison, operated patients had graft patency and limb salvage rates of 64% and 95%, respectively, at 10-year follow-up. As noted previously, these authors also found a high risk of subsequent aneurysm development in these patients. At 5-year follow-up, 32% of patients had developed additional aneurysms; at 10 years, 49% had new aneurysms.

The report by Dawson and colleagues20 and those referenced previously in the natural history section strongly support the early surgical treatment of asymptomatic femoral and popliteal aneurysms and underscore the need for careful follow-up of these patients for the development of new aneurysms.

Current recommendations for the treatment of femoral and popliteal aneurysms include aneurysms between 1.5 and 2.0 cm with thrombus and for all aneurysms of 2 cm or greater. This recommendation is based on the high incidence of thromboembolic complications associated with these lesions, as detailed earlier, and the low morbidity and mortality associated with repair.29

Treatment

Extracranial Carotid Artery Aneurysms

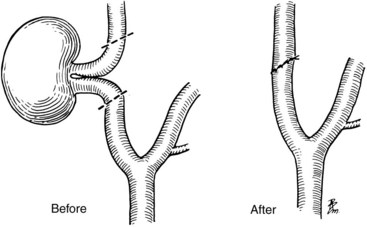

The preferred treatment is resection with primary anastomosis or graft replacement. Redundancy of the carotid artery is not uncommon when aneurysm is present. In such cases, resection of the aneurysm with mobilization of the carotid artery and primary anastomosis is sometimes easily accomplished (Figure 44-2). This technique is most applicable to internal carotid artery aneurysms. An alternative technique for flow restoration after resection of an internal carotid artery aneurysm is to divide the distal external carotid artery and perform an end-to-end anastomosis between the proximal external carotid and the distal internal carotid arteries. Aneurysms of the external carotid artery are rare and can be resected without the need to restore arterial continuity. Aneurysms of the carotid bifurcation usually require resection with graft replacement between the common and internal carotid arteries. When the internal carotid is redundant, it can be mobilized and anastomosed end to end to the common carotid artery. In both these latter cases, the external carotid is usually ligated. Aneurysms involving the common carotid artery can usually be treated by resection and primary anastomosis or graft replacement. All these procedures can be performed through a standard neck incision such as that used for carotid endarterectomy.

FIGURE 44-2 Method of end-to-end repair of a redundant internal carotid artery after aneurysm resection.

(From Trippel OH, et al: Extracranial carotid aneurysms. In Bergen JJ, Yao JST, editors: Aneurysms, New York, 1982, Grune and Stratton, pp 493–503.)

Aneurysms that involve the distal cervical internal carotid artery are often inaccessible using standard techniques. In some patients, mandibular subluxation or transection allows for the application of the previously mentioned methods of repair.30 Alternative approaches are often required for high internal carotid lesions, however. In some patients, high-fusiform aneurysms can be treated with aneurysmorrhaphy using an indwelling shunt for flow continuity and as a method of distal arterial control. In some cases, distal lesions must be treated by ligation. Unfortunately, acute occlusion of the internal carotid artery in these patients is associated with high neurologic morbidity. Stroke rates from 30% to 60% have been reported after this procedure, with half of those patients dying as a result of the stroke.10 This degree of morbidity and mortality clearly approaches that associated with the natural history of the disease.

One way to select patients who may safely undergo carotid ligation is to measure intraoperative carotid stump pressure. The carotid stump pressure can also be measured by temporary balloon occlusion at the time of arteriography using an end-hole balloon catheter.31 Stump pressures greater than 70 mm Hg appear to be safe for patients undergoing carotid ligation. Because many strokes that occur after carotid ligation manifest hours to days after the procedure, these patients should be maintained on heparin anticoagulation for 7 to 10 days postoperatively.

When stump pressure measurements indicate that carotid ligation is not safe, the performance of an extracranial-to-intracranial bypass using ipsilateral superficial temporal artery has been suggested.30 Because this procedure is generally necessary only for high internal carotid lesions, the ipsilateral external carotid artery is usually preserved, thus allowing for adequate inflow into the superficial temporal artery.

More recently, endovascular treatment modalities have become commonplace in some centers.32–34 Zhou looked at the Baylor experience from 1985 to 1994 and compared it to their experience from 1995 to 2004. All procedures were surgical during the early period, whereas during the later period 70% of procedures were endovascular, consisting of stent-grafts, stents combined with coil embolization, and endovascular occlusion.34 In some cases, coil embolization of the external carotid artery may be necessary to allow coverage of the entire aneurysm and to prevent endoleak.35 Endovascular interventions reduce the risk of cranial nerve injury, can be done without general anesthesia, are useful for distal lesions where surgical exposure is difficult, are associated with shorter hospital stays, and have lower morbidity and mortality rates.34

Subclavian and Axillary Artery Aneurysms

The surgical approach to subclavian and axillary aneurysms depends on the cause, size, and location of the aneurysm and the status of the distal circulation. Except in cases of small, asymptomatic subclavian artery aneurysms secondary to thoracic outlet (for which thoracic outlet decompression alone may be adequate), the aneurysm should be excluded and arterial continuity should be restored if possible. Proximal and distal ligation of these aneurysms has been reported. Although tissue loss does not usually occur after this procedure, claudication is not uncommon.21

When a symptomatic or large asymptomatic subclavian aneurysm is present as a result of thoracic outlet syndrome, repair of the aneurysm should be accompanied by thoracic outlet decompression. Although this combined technique has been reported through an axillary approach, the supraclavicular approach is generally preferred; this allows for safe control of the artery, although the thoracic outlet decompression is more involved. Hobson and colleagues13 recommended performing the aneurysm repair through the supraclavicular approach combined with a transaxillary approach to the first rib.

More recently, stent-grafting has been applied to carefully selected patients with subclavian aneurysms, but long-term results are not yet known.36–38 Stent-grafting of the subclavian artery can avoid major surgical procedures. Stent-grafts have been used in the treatment of true and false subclavian artery aneurysms and traumatic subclavian arteriovenous fistulae. Limitations of stent-grafting include short fixation zones and the risk of covering important vessel origins such as the right carotid, the vertebral artery, and the internal mammary artery. Concern has also been raised regarding stent compression in the area of the thoracic outlet.36–38

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree