Anatomy of the Pleura

Thomas W. Shields

Embryology

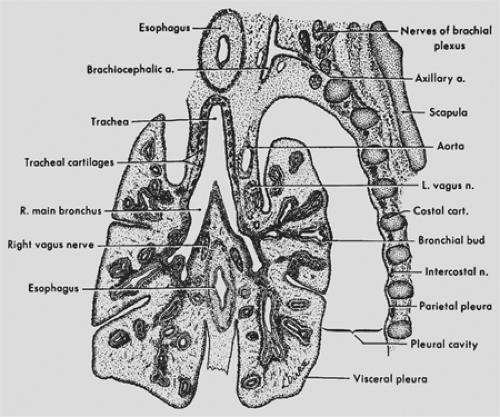

The paired pleural cavities are derivatives of the intraembryonic portion of the primitive coelom. The primitive coelom arises by splitting of the lateral mesoderm on either side of the embryo into splanchnic and somatic layers. These paired cavities are later separated by three partitions into three subdivisions: the pericardial cavity, the pleural cavities, and the peritoneal cavity. The partitions are the unpaired septum transversum, the paired pleuropericardial folds, and the paired pleuroperitoneal folds. The right and left coelomic chambers dorsal to the septum transversum remain relatively unexpanded for a period as the so-called pleural canals; these lie on either side of the mediastinal region. The development of the pleuroperitoneal folds completes the separation of the pleural canals from the other two body cavities: the pericardial cavity and the peritoneal cavity. At the fourth week of development, the laryngotracheal outgrowth from the floor of the pharynx is noted, and in the fifth week, the two lung buds begin to enlarge into the respective pleural canals. According to Patten,13 the pleural spaces open up in advance of lung growth and the lungs move (bulge) into the space prepared to receive them. With growth, the lungs and the pleuropericardial membranes come to lie on either side of the heart, and the pleuroperitoneal folds become part of the diaphragm. In this process of expansion of the lungs into the pleural canals, the splanchnic mesoderm is pushed out as a covering over the mesenchyma-packed bronchial trees (Fig. 56-1). The splanchnic mesoderm becomes thinned to form the mesothelial layer of the pleura, and the mesenchymal tissue immediately beneath this layer becomes the connective tissue of the pleura. The splanchnic mesoderm is thus the origin of the visceral pleura, and the somatic mesoderm is the origin of most of the parietal pleura.

Histology

The two pleural layers have similar histologic features with the exception of the presence of stomata in the parietal pleura that are absent in the visceral pleura. According to Antony and colleagues,2 each layer consists of (a) an innermost mesothelial cell layer, (b) a submesothelial interstitial connective tissue layer (macula cribriformis), (c) an inner thin elastic fiber layer, (d) an outer interstitial connective tissue layer, and (e) a thick elastic fiber layer. In addition, according to Hammer,9 a fatty layer separates the parietal pleura and the muscles of the chest wall. The mesothelial cells in both visceral or parietal pleura, according to Wang,20,21 vary in thickness from <1 to >4 μm and from 16.4 ± 6.8 to 41.9 ± 9.5 μm in diameter. Their shape may vary according to their location in the pleural membrane.

Ultrastructurally, the mesothelial cells demonstrate microvilli. Tight apical junctions are present, but gap junctions, desmosomes, or half desmosomes occur infrequently on the basal part of the cell membrane.

Immunohistochemically, the mesothelial cells, as reported by Dervan5 and Bolen3 and their associates, express both low- and high-molecular-weight cytokeratin. The normal mesothelial cells are negative for reaction to vimentin, epithelial membrane antigen, carcinoembryonic antigen, and factor VIII–related antigen.

Beneath the basal membrane of the mesothelial layer is a collection of loose connective tissue (macula cribriformis). This submesothelial layer contains collagen tissue, elastic fibers, small blood vessels, lymphatic networks, and nerve fibers. The mesenchymal cells in this layer—according to Keating,10 Said,16 and England6 and their coworkers—have the characteristics of fibroblasts. The cells are negative for cytokeratin, carcinoembryonic antigen, and factor VIII–related antigen.

The visceral and parietal pleural layers are approximately the same thickness, averaging 30 to 40 μm.17 Large dehiscences, or stomata, have been documented in the parietal pleura. These stomata, ranging from 2 to >6 μm in diameter, connect the pleural cavity with the subpleural lymphatic network and permit egress of material into the lymphatics from the pleural space.4 Wang20 has described focal accumulations of macrophages along with pluripotential mesenchymal, lymphoid, and plasma cells (called Kampmeier’s foci) in the caudal portions of the mediastinal pleura that may be functionally related to the stomata.

Gross Anatomic Features

The visceral pleura is closely applied to the lung surfaces from the hila outward. It lines the major and minor fissures to the extent that each is developed; the minor fissure on the right may be incomplete to absent in 50% of humans. It may also delineate the various accessory fissures (see Chapter 5) when present. The pulmonary ligament, which extends caudad from each hilus to near the diaphragm, consists of two apposed layers of visceral (splanchnic) pleura and becomes continuous with the parietal pleura.

The visceral pleura adheres to the lung parenchyma. A naturally occurring cleavage plane is absent. When the visceral pleura is stripped from the lung parenchyma, a raw surface with innumerable air leaks and at times small bleeding vessels is left behind.

The parietal pleura lines the chest wall (the costal pleura), the mediastinum, and the diaphragm and forms the cupula or pleural dome at the thoracic inlet bilaterally. The mediastinal pleura extends from the sternum ventrally to the thoracic spine dorsally and covers the mediastinal structures and the pericardium. The diaphragmatic pleura adheres tightly to the diaphragmatic tissues; a cleavage plane between the two is basically nonexistent. Similarly, the mediastinal pleura is densely adherent to the pericardium. In contrast, the remainder of the mediastinal pleura, the pleura of the cupula, and the costal pleura can be readily dissected from the underlying tissues. The plane of cleavage from the chest wall is between the loose connective and fatty tissue layer and the endothoracic fascia attached to the underlying osseous, muscular, and vascular structures of the chest wall.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree