4

CHAPTER

![]()

Airspace-Predominant Diseases

This chapter includes diseases in which the predominant histologic changes occur within airspaces, including bronchiolar lumens, alveolar duct lumens, and alveolar spaces, rather than in the interstitium. It should be remembered that pure airspace disease without any interstitial abnormality, just like pure interstitial disease without airspace changes, is rare, and judging which site of involvement is predominant is an important first step in pathologists’ evaluation. Categorization of diseases in this manner, however, is provided simply to facilitate diagnosis for the pathologist, and should not be considered a replacement for other currently accepted classification schemes.

In contrast to many interstitial diseases that affect both lungs diffusely, many airspace-predominant diseases manifest localized infiltrates. For purposes of this discussion, the radiographically localized and the radiographically diffuse airspace diseases are reviewed separately.

TOPICS

I. Usually Localized or Patchy Radiographically:

Organizing Pneumonia (OP)

Organizing Pneumonia (OP)

Eosinophilic Pneumonia

Eosinophilic Pneumonia

Aspiration Pneumonia

Aspiration Pneumonia

Exogenous Lipoid Pneumonia

Exogenous Lipoid Pneumonia

II. Usually Diffuse Radiographically:

Respiratory Bronchiolitis Interstitial Lung Disease/Desquamative Interstitial Pneumonia (RBILD/DIP)

Respiratory Bronchiolitis Interstitial Lung Disease/Desquamative Interstitial Pneumonia (RBILD/DIP)

Alveolar Hemorrhage Syndromes

Alveolar Hemorrhage Syndromes

Pulmonary Alveolar Proteinosis (PAP)

Pulmonary Alveolar Proteinosis (PAP)

Pulmonary Alveolar Microlithiasis (PAM)

Pulmonary Alveolar Microlithiasis (PAM)

ORGANIZING PNEUMONIA (OP)

Formerly termed bronchiolitis obliterans–organizing pneumonia (BOOP), organizing pneumonia (OP) is commonly encountered on lung biopsies.

Histologic Features

Airspace filling by fibroblast plugs containing variable numbers of chronic inflammatory cells within myxoid stroma

Airspace filling by fibroblast plugs containing variable numbers of chronic inflammatory cells within myxoid stroma

Peribronchiolar distribution with variable involvement of small bronchioles, alveolar ducts, and peribronchiolar alveolar spaces

Peribronchiolar distribution with variable involvement of small bronchioles, alveolar ducts, and peribronchiolar alveolar spaces

Intact alveolar septa with mild interstitial inflammation

Intact alveolar septa with mild interstitial inflammation

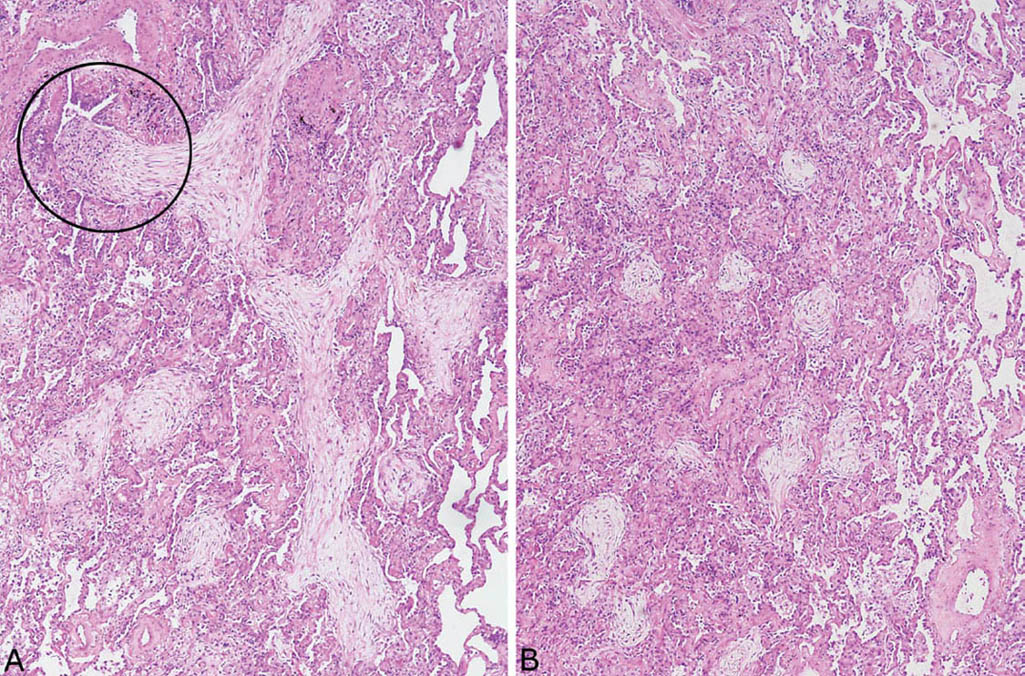

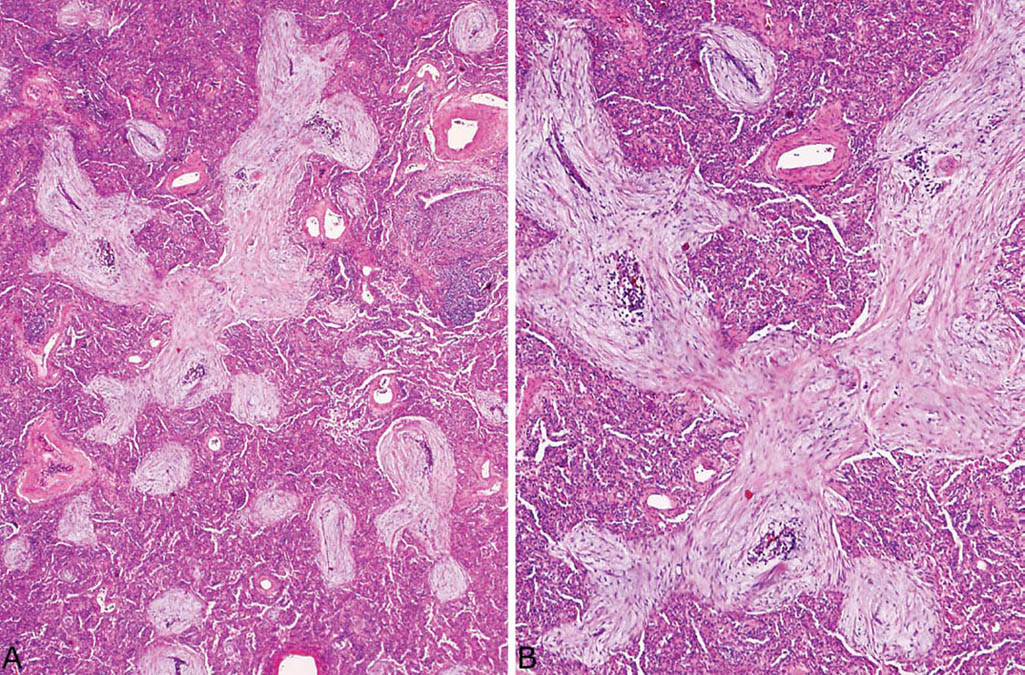

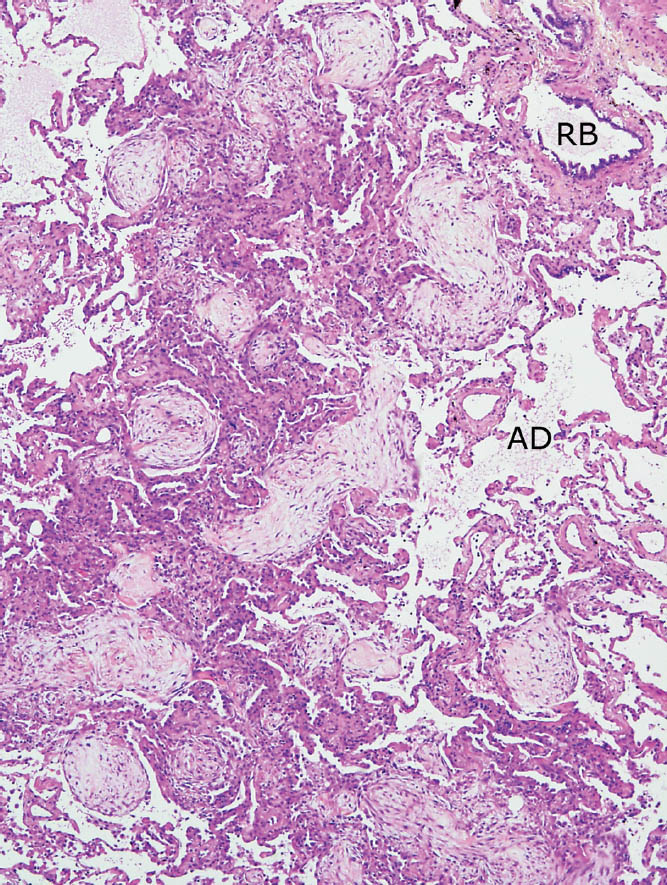

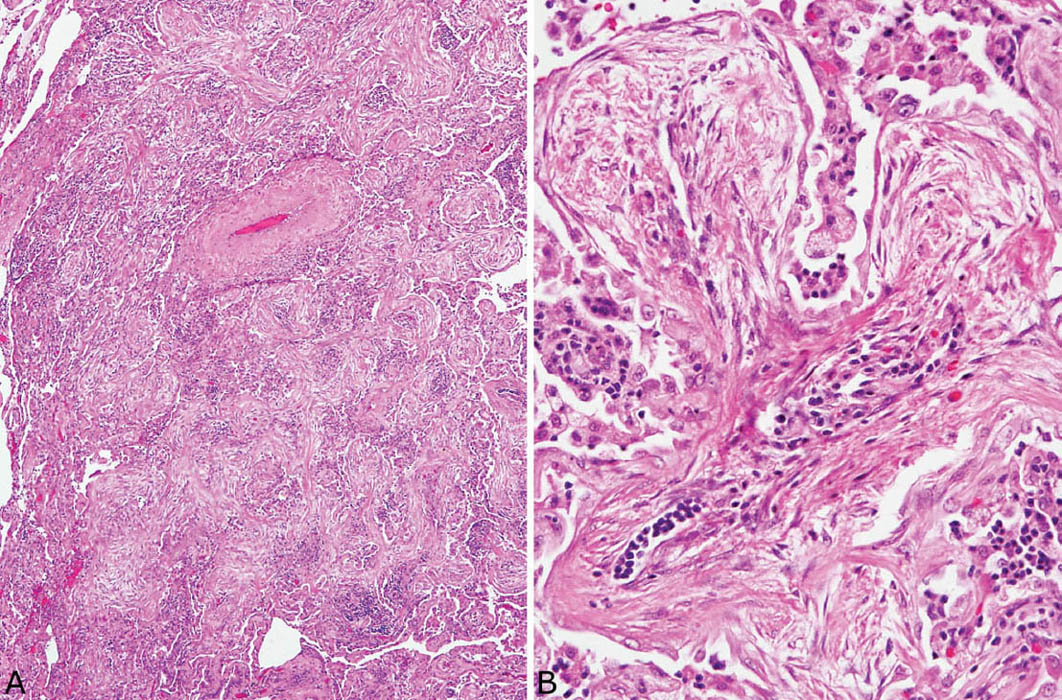

The histologic hallmark of OP is the filling of airspaces by plugs composed of fibroblasts and myofibroblasts combined with variable numbers of admixed chronic inflammatory cells (Figures 4.1 and 4.2). The process is easy to recognize at low magnification because the involved parenchyma appears consolidated with loss of normal airspaces, although the alveolar architecture remains intact, and the fibroblast plugs have a lightly staining myxoid stroma that stands out against the darker staining lung. The changes may be patchy and well demarcated from adjacent parenchyma (Figures 4.1 and 4.3) or, less often, they involve the lung diffusely. A peribronchiolar distribution is characteristic and easily recognizable when residual bronchioles are identified within the process. The bronchioles may contain fibroblast plugs (hence the term bronchiolitis obliterans–organizing pneumonia in older literature), but frequently normal or mildly inflamed bronchioles are present within the areas of OP (Figures 4.2A, 4.3, and, 4.4). Sometimes, bronchioles are not visible, and the peribronchiolar distribution can be appreciated only by location of the changes around a pulmonary artery where a bronchiole normally would be found (Figure 4.5). The fibroblast plugs vary in shape because they conform to the shape of the underlying airspace, including round to elongated when present in bronchioles, serpiginous and branching when in alveolar ducts, and small and round when in alveolar spaces.

FIGURE 4.1 Organizing pneumonia. (A) Filling of airspaces by lightly staining fibroblast plugs with minimal associated inflammation. One elongated, branching fibroblast plug is arising in a respiratory bronchiole (circle, top left) and filling the adjacent alveolar duct. Some adjacent fibroblast plugs appear rounded due to involvement of alveolar spaces. (B) In this field from the same case, alveolar spaces are filled by rounded fibroblast plugs. The process is sharply demarcated from uninvolved airspaces (right).

FIGURE 4.2 Organizing pneumonia. (A) An alveolar duct (top center) is filled by an elongated, branching fibroblast plug, while smaller rounded plugs are present within nearby alveoli. An inflamed bronchiole is present at the upper right. (B) Higher magnification of a fibroblast plug in (A) showing the characteristic spindle-shaped fibroblasts and myofibroblasts within lightly staining stroma. Foci of chronic inflammation are admixed with the spindled cells in places.

FIGURE 4.3 Organizing pneumonia. Patchy, bronchiolocentric distribution is noted in this example with areas of alveolar filling by fibroblast plugs present in parenchyma surrounding a respiratory bronchiole (RB) and adjacent alveolar duct (AD). The process is sharply demarcated from surrounding normal parenchyma.

At higher magnification, the fibroblast plugs are composed of elongated, spindle-shaped cells within lightly staining stroma, and there are variable numbers of admixed chronic inflammatory cells, including lymphocytes, plasma cells, and macrophages (Figures 4.2B and 4.5). Scattered eosinophils are occasionally present, but, if numerous, the possibility of organizing eosinophilic pneumonia (see subsequent section, “Eosinophilic Pneumonia”) should be considered. Neither giant cells nor granulomas are features of ordinary organizing pneumonia, and, if present, should suggest another process, especially aspiration pneumonia (see subsequent section, “Aspiration Pneumonia”). The “BOOP-like” variant of granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Wegener granulomatosis) might also enter the differential diagnosis if vasculitis is present (see Chapter 6, Figure 6.13).

Foamy macrophages are often prominent in adjacent alveolar spaces, and there may be admixed chronic inflammatory cells (Figures 4.5B and 4.6). Sometimes a fibrinous exudate, containing scattered fibroblasts and chronic inflammatory cells, is present within airspaces in addition to the typical fibroblast plugs (Figure 4.7). This finding likely represents an early stage of organization. Rarely, it is the only finding, and although we consider such cases to be a variant of OP, some have termed the lesion acute fibrinous and organizing pneumonia (AFOP, Figure 4.8).

The alveolar septa within the areas of OP usually show nonspecific thickening with a mild chronic inflammatory cell infiltrate and variable alveolar pneumocyte hyperplasia (Figures 4.6 and 4.7). This mild interstitial pneumonia is usually confined to the OP areas or immediately adjacent parenchyma and generally does not extend into more distal alveolar septa.

Differential Diagnosis

The diagnosis of OP is usually straightforward, but in the uncommon instance when the changes are extensive and involve both lungs diffusely, organizing diffuse alveolar damage (DAD) enters the differential diagnosis (see Chapter 5, Table 5.1). Both the peribronchiolar distribution and the predominantly airspace involvement characteristic of OP may be obscured in such cases. The presence of other features of acute lung injury (hyaline membranes, small thrombi, squamous metaplasia) as well as a history of mechanical ventilation would support DAD over OP.

It is important to remember that OP can be a prominent finding in other unrelated conditions, and, therefore, whenever unusual features are present (vasculitis, giant cells, eosinophils, acute inflammation, necrosis, for example), careful search should be undertaken for an underlying primary lesion.

Occasionally the fibroblast plugs of OP may be difficult to distinguish from fibroblast foci of usual interstitial pneumonia. Their contrasting features are summarized in Chapter 3, Table 3.1.

Terminology (OP Versus BOOP Versus COP)

OP is a purely descriptive, generic term for pathologic changes that may cause clinically evident disease, including conditions with known etiology as well as idiopathic disease. It also may occur as a minor component of another disease or as an incidental reactive change on the edge of an unrelated process. OP largely replaces the older term “bronchiolitis obliterans-organizing pneumonia (BOOP),” which refers to the same pathologic entity but often was misinterpreted by clinicians as representing an idiopathic disease. To avoid this confusion, the term “cryptogenic organizing pneumonia (COP)” is generally used for the idiopathic disease, although “idiopathic BOOP” is also acceptable and may be more familiar to clinicians. For the pathology report, however, it is best to diagnose “OP” rather than trying to pigeonhole the case into a clinical syndrome.

FIGURE 4.4 Organizing pneumonia. (A) The lumen of a small bronchiole is filled by a fibroblast plug in this example as are the lumens of nearby alveolar ducts and spaces, hence the older term, bronchiolitis obliterans–organizing pneumonia (BOOP). (B) Fibroblast plugs involving bronchioles are not always found, as illustrated in this example, in which a normal bronchiole (upper right) is present adjacent to the organizing pneumonia. The elongated shape of the nearby fibroblast plug indicates alveolar duct involvement.

FIGURE 4.5 Organizing pneumonia. (A) In this example, air spaces around a small artery (upper center) are uniformly obliterated and the bronchiolocentric localization is inferred by the presence of the changes adjacent to an artery where a bronchiole normally resides. (B) At higher magnification a branching fibroblast plug within an alveolar duct shows mild chronic inflammation admixed with the typical fibroblasts. Foamy macrophages along with scattered chronic inflammatory cells are present in adjacent airspaces.

FIGURE 4.6 Organizing pneumonia. (A) Foamy macrophages fill airspaces adjacent to a fibroblast plug (top left). Note also the accompanying mild chronic interstitial pneumonia that thickens adjacent alveolar septa. (B) Higher magnification showing the foamy macrophages within airspaces and thickened adjacent alveolar septa.

FIGURE 4.7 Organizing pneumonia. (A) In this example, a fibrinous exudate and chronic inflammatory cells are admixed with the fibroblast plugs within airspaces. (B) Higher magnification showing the mixture of chronic inflammatory cells and fibroblasts within the fibrinous exudate. Note also the accompanying chronic interstitial pneumonia. Although the interstitial changes are prominent in this case, obliteration of airspaces is the predominant finding.

FIGURE 4.8 Acute fibrinous and organizing pneumonia (AFOP). (A) At low magnification, the airspaces are filled by a predominantly fibrinous exudate within peribronchiolar airspaces. (B) Higher magnification better details the fibrinous exudate containing a few intermingled fibroblasts.

Etiology and Pathogenesis

OP represents a reaction to acute lung injury that affects small bronchioles and peribronchiolar parenchyma. The process is analogous to DAD (see Chapter 5), except that DAD involves distal alveoli preferentially rather than peribronchiolar parenchyma. The most common potential causes of OP are listed in Table 4.1, and these should be excluded clinically before the idiopathic disease, COP, is considered.

Clinical Features of COP

The onset of COP is usually subacute, occurring over weeks to months. Patients commonly complain of fever, cough, and dyspnea, and there may be a history of an antecedent upper respiratory infection or pneumonia. Patchy ground glass opacities or areas of consolidation that may be multiple and bilateral are common chest CT findings. Most patients respond favorably to corticosteroid therapy, and the prognosis is good with recovery in about 85%.

TABLE 4.1 Common Causes of OP

|

|

|

|

|

BOOP, bronchiolitis obliterans–organizing pneumonia; COP, cryptogenic organizing pneumonia; OP, organizing pneumonia.

Helpful Tips—OP

The diagnosis of COP can only be made clinically after all potential causes of OP have been excluded.

The diagnosis of COP can only be made clinically after all potential causes of OP have been excluded.

In difficult cases, the presence of hyaline membranes, small arterial thrombi, areas of squamous metaplasia, or a history of ventilator therapy indicate organizing DAD rather than OP (see Chapter 5, Table 5.1).

In difficult cases, the presence of hyaline membranes, small arterial thrombi, areas of squamous metaplasia, or a history of ventilator therapy indicate organizing DAD rather than OP (see Chapter 5, Table 5.1).

The significance of OP in transbronchial biopsy specimens should be interpreted with caution, because OP may occur as a nonspecific reactive change around other lesions, and it is difficult to know whether the biopsy has adequately sampled the lesion in question or only its periphery.

The significance of OP in transbronchial biopsy specimens should be interpreted with caution, because OP may occur as a nonspecific reactive change around other lesions, and it is difficult to know whether the biopsy has adequately sampled the lesion in question or only its periphery.

EOSINOPHILIC PNEUMONIA

Histologic Features

Airspace filling by eosinophils admixed with variable numbers of macrophages

Airspace filling by eosinophils admixed with variable numbers of macrophages

Variable accompanying interstitial inflammation

Variable accompanying interstitial inflammation

Absent parenchymal necrosis or significant fibrosis

Absent parenchymal necrosis or significant fibrosis

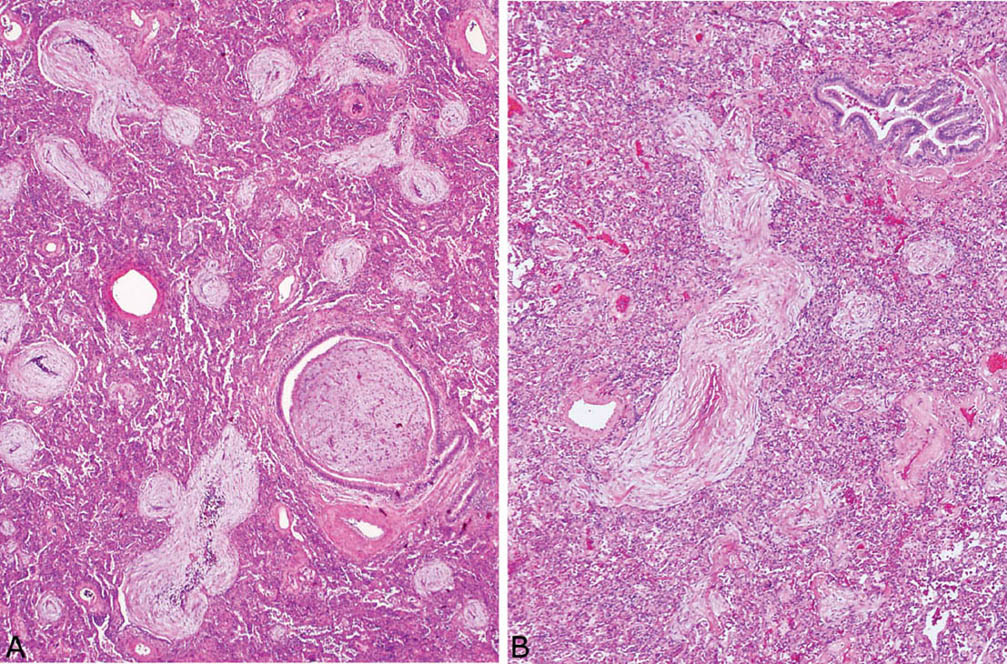

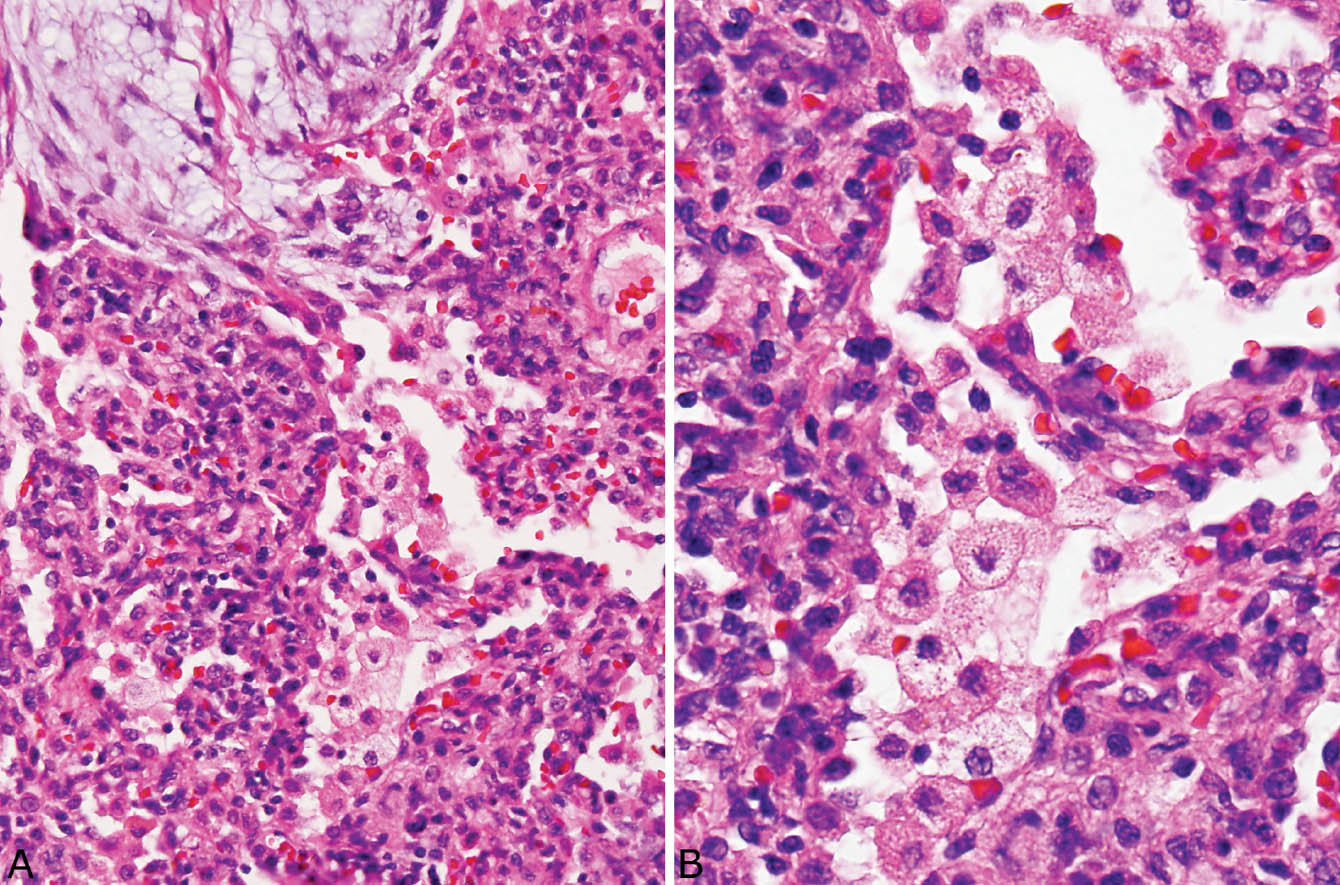

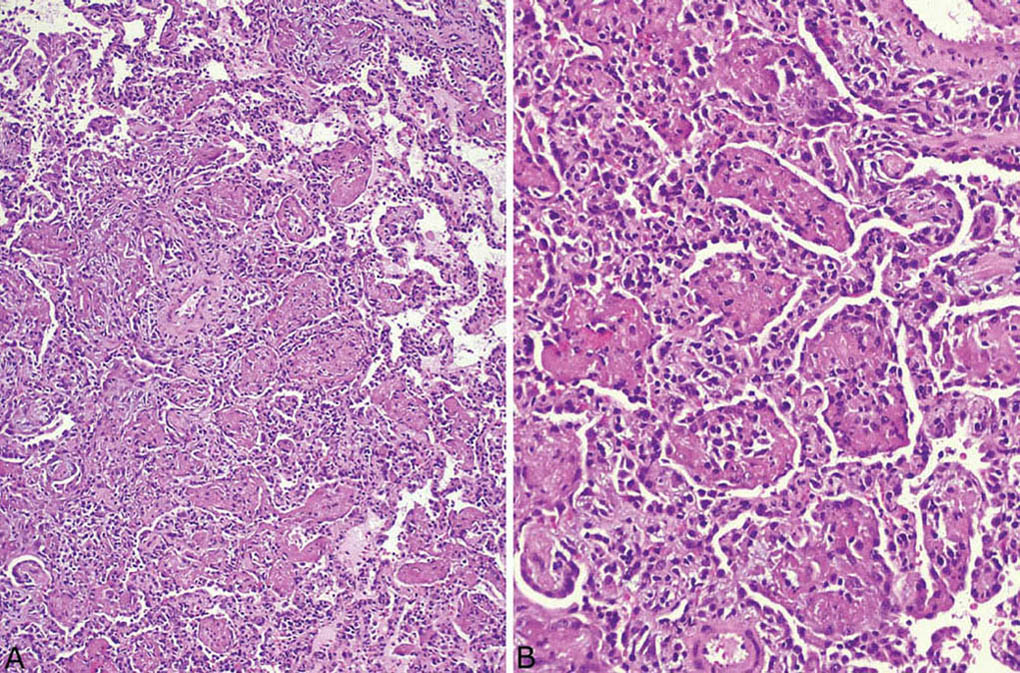

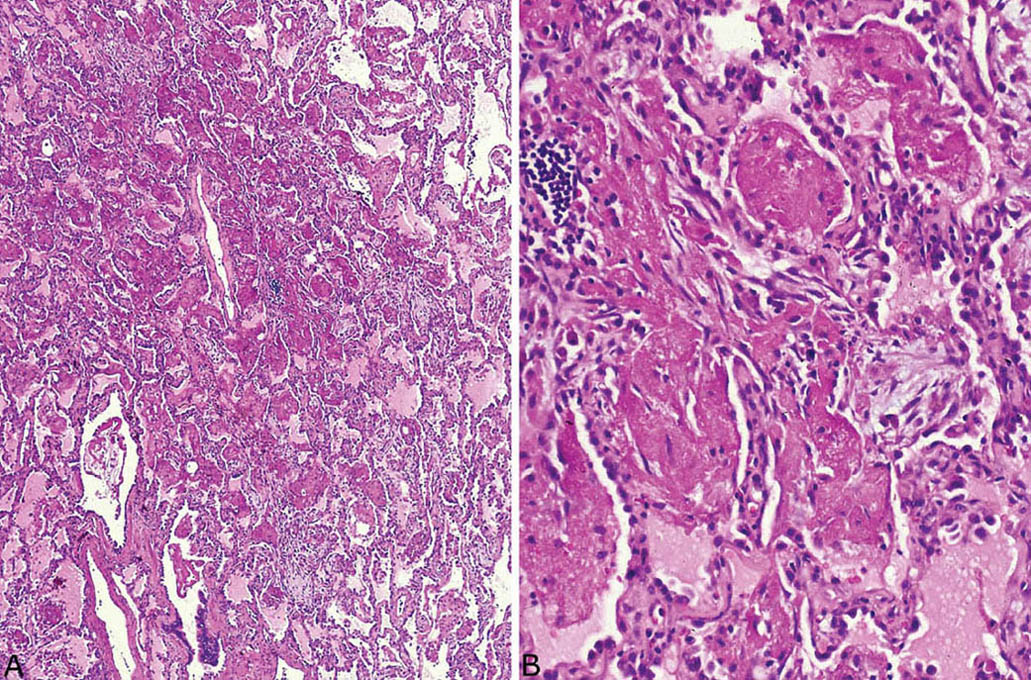

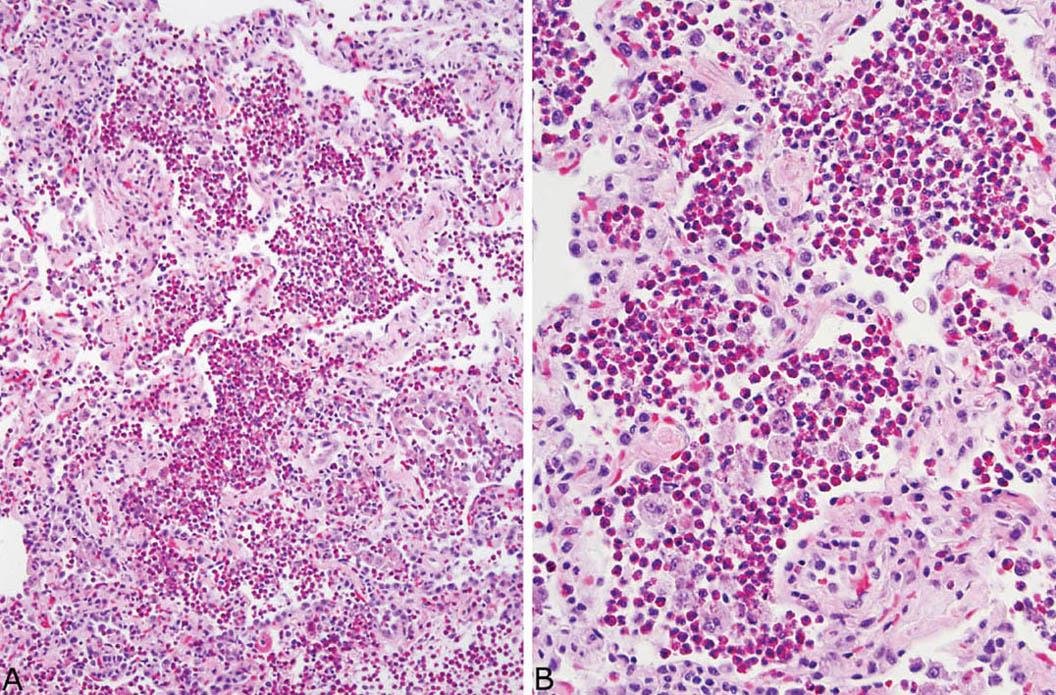

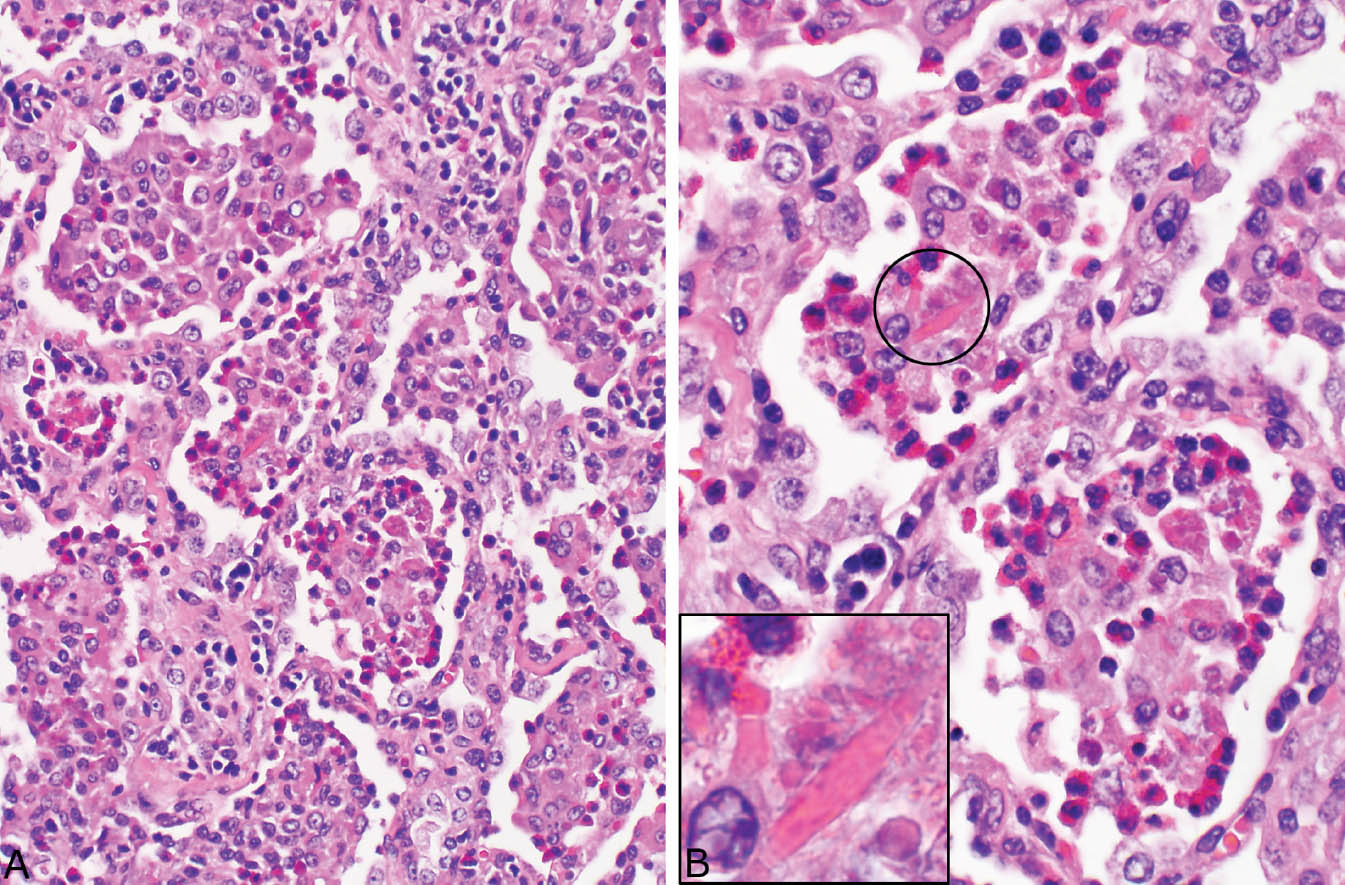

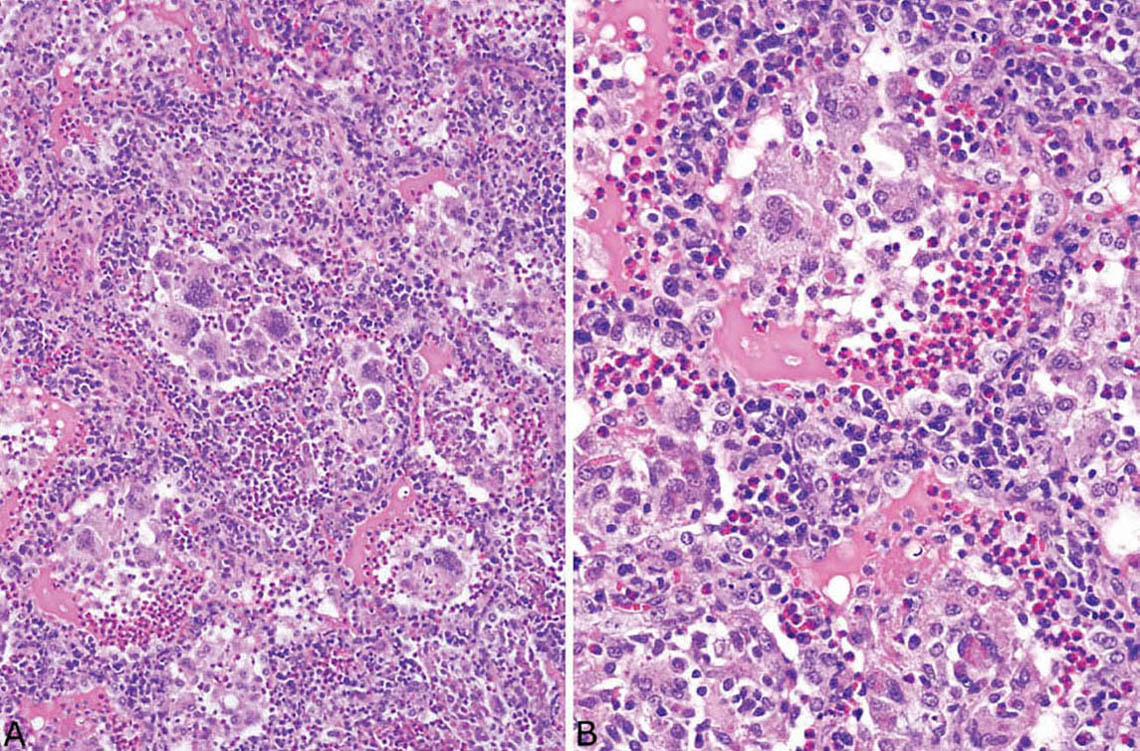

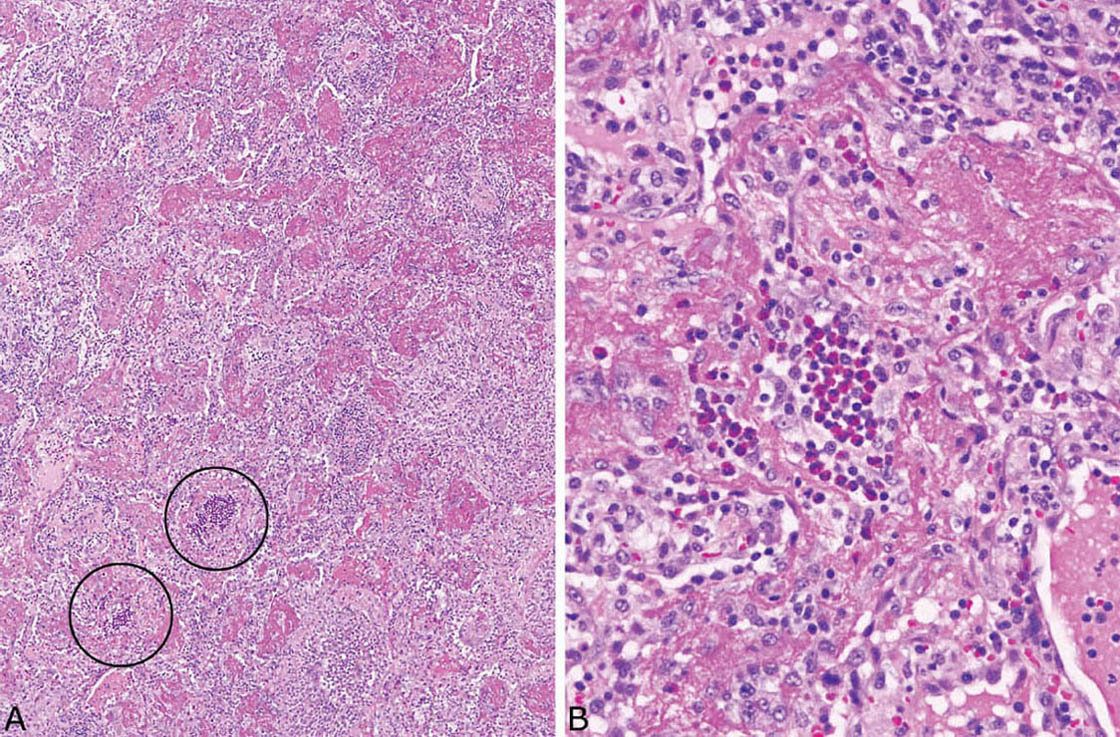

Large numbers of eosinophils within intact airspaces comprise the main finding in eosinophilic pneumonia (Figure 4.9). Variable numbers of macrophages are admixed with the eosinophils and their relative proportions vary from case to case and from area to area (Figure 4.10). The macrophage cytoplasm occasionally contains remnants of eosinophil granules and rarely Charcot–Leyden crystals, which are related to eosinophil breakdown products (Figure 4.10B). In some cases multinucleated giant cells are numerous within the airspace exudate (Figure 4.11). A fibrinous intra-alveolar exudate suggestive of acute fibrinous and organizing pneumonia (AFOP, see earlier section, “Organizing Pneumonia” and “Histologic Features”) may be seen within airspaces in some cases, but the presence of numerous eosinophils, at least focally, is diagnostic (Figure 4.12). Clusters of necrotic eosinophils, sometimes surrounded by histiocytes (eosinophil abscesses), are occasionally observed within airspaces (Figure 4.13). Importantly, eosinophil abscesses occur only within the airspaces and are not associated with parenchymal necrosis. The airspace exudate may undergo organization in places with replacement by fibroblast plugs resembling ordinary organizing pneumonia except for the presence of numerous admixed eosinophils.

A mild cellular interstitial pneumonia usually accompanies the airspace exudate, and is characterized by a mixture of lymphocytes, plasma cells, and variable numbers of eosinophils within alveolar septa accompanied by alveolar pneumocyte hyperplasia (Figures 4.10 and 4.11B). Interstitial fibrosis, however, is not a feature. The interstitial inflammatory infiltrate commonly extends into the walls of nearby blood vessels (Figure 4.14), but a destructive, necrotizing vasculitis is not seen. The presence of vascular inflammation in otherwise typical eosinophilic pneumonia should not be interpreted as indicative of Churg–Strauss syndrome (eosinophilic polyangiitis with granulomatosis, see subsequent section, “Differential Diagnosis,” and Chapter 6).

FIGURE 4.9 Eosinophilic pneumonia. (A) Low magnification showing filling of airspaces by large numbers of eosinophils. The alveolar septa are mildly thickened. (B) Higher magnification showing numerous eosinophils and scattered macrophages within airspaces.

FIGURE 4.10 Eosinophilic pneumonia. (A) In this example, macrophages predominate in some airspaces and eosinophils in others. There is also an accompanying mild interstitial pneumonia. (B) Higher magnification of (A) shows the mixture of eosinophils and macrophages. Occasionally, Charcot–Leyden crystals (circle and inset) are present within the intra-alveolar exudate.

FIGURE 4.11 Eosinophilic pneumonia. (A) In this example, multinucleated giant cells are prominent within the intra-alveolar exudate. (B) Higher magnification shows the multinucleated giant cells and macrophages admixed with numerous eosinophils. There is also a prominent chronic interstitial pneumonia with a mixture of lymphocytes, plasma cells, and eosinophils thickening alveolar septa.

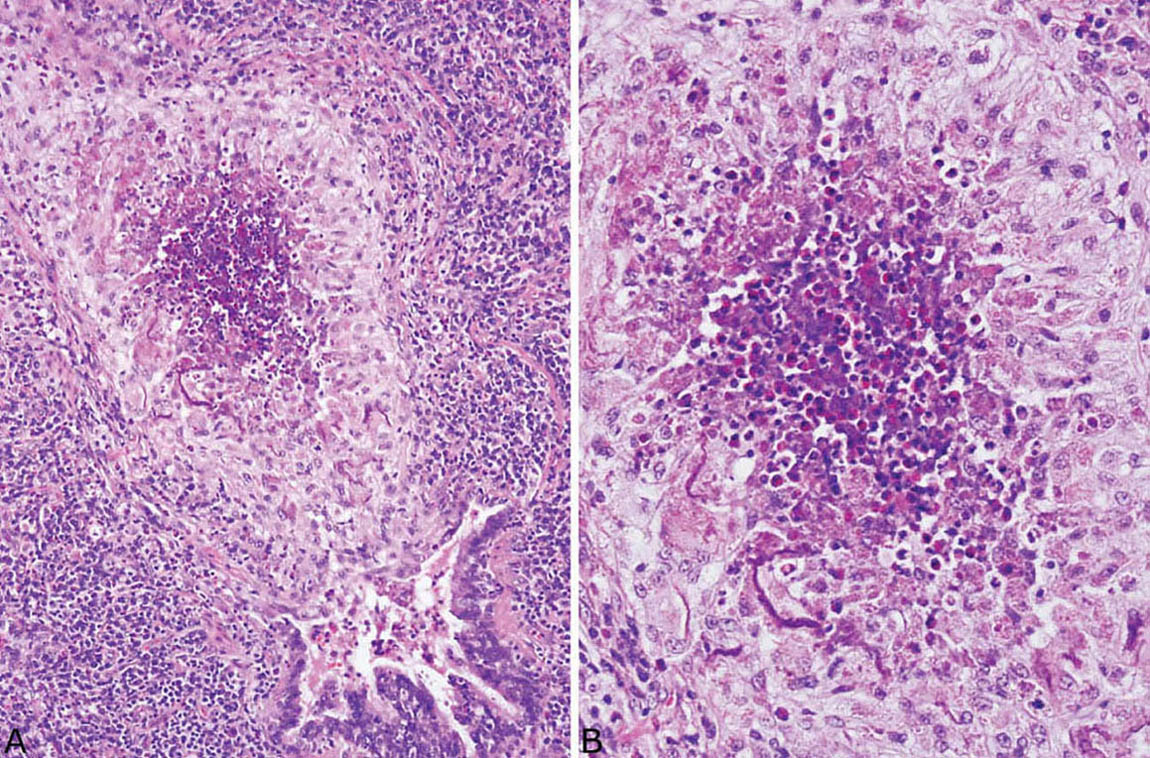

FIGURE 4.12 Eosinophilic pneumonia. (A) In this case, a fibrinous exudate that superficially resembles acute fibrinous and organizing pneumonia (AFOP) is prominent within airspaces, and the diagnostic eosinophil clusters are present only focally (circles). (B) Higher magnification shows a diagnostic eosinophil cluster within surrounding fibrinous exudate.

FIGURE 4.13 Eosinophilic pneumonia. (A) An eosinophil abscess is present within the lumen of a respiratory bronchiole. Note that the surrounding bronchiole wall is intact, although inflamed, and parenchymal necrosis is absent. (B) Higher magnification shows necrotic eosinophils in the center surrounded by epithelioid histiocytes, many of which have ingested eosinophil granules.

Differential Diagnosis

Relatively few lung diseases contain prominent eosinophil infiltrates. Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH, formerly eosinophilic granuloma; see Chapter 2) enters the differential diagnosis when eosinophils are prominent. That lesion is patchy with peribronchiolar distribution and the eosinophils are mainly interstitial, not intra-alveolar. Additionally, diagnostic clusters of Langerhans cells that mark with CD1a and S-100 immunostains are present in the interstitium. Although macrophages characteristic of respiratory bronchiolitis (Chapter 11) may be numerous within adjacent airspaces, they have yellow-brown pigmented cytoplasm and are not admixed with eosinophils.

Eosinophils may be prominent in certain infections, especially coccidioidomycosis and parasitic infestations (see Chapter 8), and occasionally in granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Wegener granulomatosis; see Chapter 6). The presence of parenchymal necrosis and granulomatous inflammation in such cases militates against eosinophilic pneumonia.

Eosinophilic pneumonia is one manifestation of Churg–Strauss syndrome (eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis, Chapter 6), and it may be the only finding in some cases, but in the absence of an accompanying necrotizing vasculitis and granulomatous inflammation that diagnosis cannot be made from the pathologic findings. In most cases, Churg–Strauss syndrome is diagnosed based on clinical findings including asthma, blood eosinophilia, pulmonary infiltrates, and extrapulmonary vasculitis often with positive antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA) serology.

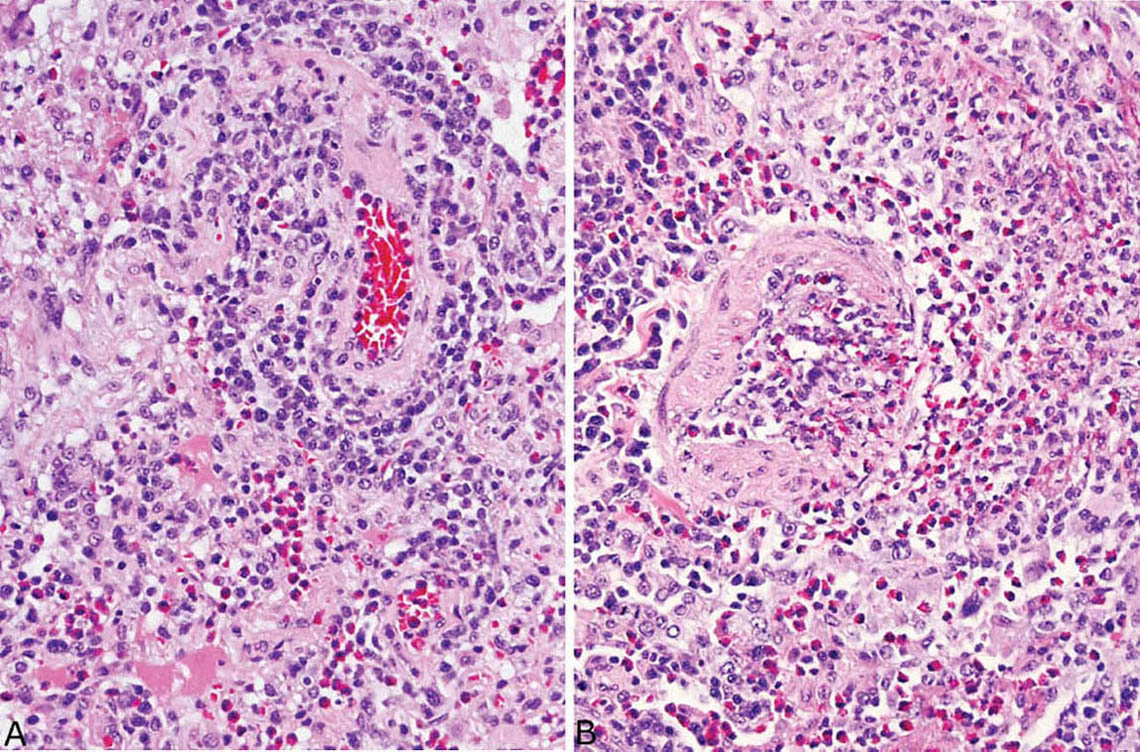

FIGURE 4.14 Vasculitis in eosinophilic pneumonia. (A) A perivascular chronic inflammatory cell infiltrate containing varying numbers of eosinophils and chronic inflammatory cells is common, as in the artery at upper right. (B) A transmural infiltrate may be present in some blood vessels as seen focally in this artery, but a true necrotizing vasculitis is not seen. By itself, such vascular inflammation should not be interpreted as indicating Churg–Strauss syndrome (eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis; see Chapter 6).

Clinical Features

Most cases of eosinophilic pneumonia that come to biopsy fall into the category of chronic eosinophilic pneumonia. The onset is usually subacute with fever, dyspnea, and malaise occurring over several weeks. Women are affected more often than men, and a history of asthma is common. Blood eosinophilia may or may not be present. Radiographically, patchy, often peripheral infiltrates are common, and they may be transient, regressing, and recurring over time. Most patients respond favorably to corticosteroid therapy, although recurrences are common. Although most cases are idiopathic, a number of potential etiologies should be excluded, especially drug toxicity, fungal hypersensitivity (allergic bronchopulmonary fungal disease, see Chapter 11), parasitic infestations, and inhalants such as crack cocaine.

Rare cases present acutely with a febrile illness associated with bilateral lung infiltrates and respiratory failure occurring over about 1 week. This condition known as acute eosinophilic pneumonia most often is diagnosed clinically with bronchoalveolar lavage, and usually does not require biopsy for diagnosis. The histologic features are similar to ordinary eosinophilic pneumonia, except that hyaline membranes may also be present.

Helpful Tips—Eosinophilic Pneumonia

Vascular inflammation is common in uncomplicated eosinophilic pneumonia, and should not be interpreted as indicating an underlying systemic vasculitis such as Churg–Strauss syndrome.

Vascular inflammation is common in uncomplicated eosinophilic pneumonia, and should not be interpreted as indicating an underlying systemic vasculitis such as Churg–Strauss syndrome.

The presence of significant fibrosis, parenchymal destruction, or necrosis should indicate a diagnosis other than eosinophilic pneumonia.

The presence of significant fibrosis, parenchymal destruction, or necrosis should indicate a diagnosis other than eosinophilic pneumonia.

ASPIRATION PNEUMONIA

Aspiration pneumonia most often is encountered clinically as an acute necrotizing bacterial bronchopneumonia related to aspiration of mouth organisms usually following loss of consciousness. Such cases are diagnosed on clinical grounds without biopsy. Other cases may be due to food or other particulate matter aspiration and are most often observed at autopsy as terminal events in debilitated patients. Less commonly, aspiration of particulate matter occurs in previously healthy persons and may be unsuspected clinically. Diagnosis in those cases is usually made by lung biopsy. Exogenous lipoid pneumonia is another variant of aspiration pneumonia that may require biopsy and is described in the next section, “Exogenous Lipoid Pneumonia.”

Histologic Features

Peribronchiolar foreign material, usually vegetable particles or fillers from oral medications with variable inflammatory reaction

Peribronchiolar foreign material, usually vegetable particles or fillers from oral medications with variable inflammatory reaction

Frequent organizing pneumonia and multinucleated giant cells

Frequent organizing pneumonia and multinucleated giant cells

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree