20 Acute Pulmonary Embolism Acute pulmonary embolism is a typical complication of the hospitalized and bedridden patient. The underlying cause is almost always a deep vein thrombosis of the lower extremity and less frequently of the upper extremity. The acute obstruction of the pulmonary arterial vasculature by the embolus and the release of bronchoconstricting mediators result in an increase of the pulmonary vascular resistance and in an acute pressure overload of the right ventricle. Consequences are A large pulmonary embolus (or emboli) that causes sudden obstruction of more than two-thirds of the pulmonary vasculature results in acute right ventricular failure and frequently death. Pulmonary infarctions are exceptionally rare due to the additional blood supply via the bronchial arteries. Early, useful noninvasive diagnostic tools include clinical signs and symptoms, ECG, chest radiography, laboratory values (including blood gases and D-dimers), and echocardiography, which may demonstrate signs of right ventricular strain and can provide systolic pulmonary artery pressure. Depending upon early test results, additional tests such as spiral CT/angio CT of the pulmonary arteries and venous studies such as compression and duplex ultrasound can be employed. In stable, chronic patients and ambiguous findings a perfusion–ventilation scan can be performed. In addition, MR angiography can directly demonstrate a thrombus. The primary significance of the nuclear scan lies in its ability to rule out the diagnosis when the findings are unremarkable. In emergencies, the nuclear scan plays a subordinate role. Conventional pulmonary angiography is performed only in specific situations. The decision to use direct pulmonary angiography usually depends on the patient’s clinical status. Pulmonary angiography is indicated in the following cases: Thus, there is no indication for pulmonary angiography in patients with already confirmed pulmonary embolism and hemodynamic stability. Hemodynamic function depends on the extent of the vascular obstruction. With an obstruction of ≤ 30 % of the pulmonary vasculature, the mean pulmonary artery pressure and the right atrial pressure can still be normal. If > 50 % of the pulmonary vasculature is obstructed, cardiac output decreases and thus also systemic arterial pressure. Systolic right ventricular pressure is equal to the systolic PA pressure, and the right ventricular enddiastolic pressure is also increased as a sign of acute right ventricular failure. A classification of the severity of an acute pulmonary embolism according to hemodynamic and clinical criteria is shown in Table 20.1. Direct signs of an acute pulmonary embolus (Fig. 20.2) are

Basics

Basics

The most important primary risk factors include protein C and S deficiency, antithrombin III, factor V Leiden mutation (APC resistance), anticardiolipin antibodies, and hyperhomocysteinemia.

The most important primary risk factors include protein C and S deficiency, antithrombin III, factor V Leiden mutation (APC resistance), anticardiolipin antibodies, and hyperhomocysteinemia.

The most important secondary risk factors include trauma, surgery, age, stroke, immobilization, and malignant diseases.

The most important secondary risk factors include trauma, surgery, age, stroke, immobilization, and malignant diseases.

Dilatation of the right ventricle with global hypokinesia

Dilatation of the right ventricle with global hypokinesia

Increase of right ventricular end-diastolic pressure

Increase of right ventricular end-diastolic pressure

Increase of mean right atrial pressure

Increase of mean right atrial pressure

Decrease of right ventricular cardiac output with decrease of left ventricular preload and reduction of systemic arterial pressure with tachycardia

Decrease of right ventricular cardiac output with decrease of left ventricular preload and reduction of systemic arterial pressure with tachycardia

Indication

Indication

When a pulmonary embolism is suspected and the patient’s clinical status requires the immediate confirmation of the diagnosis

When a pulmonary embolism is suspected and the patient’s clinical status requires the immediate confirmation of the diagnosis

When a catheter intervention is planned with the angiography

When a catheter intervention is planned with the angiography

When the diagnosis cannot be confirmed or excluded by noninvasive diagnostic tests

When the diagnosis cannot be confirmed or excluded by noninvasive diagnostic tests

Procedure

Procedure

Prior to puncture, perform compression/duplex ultrasound of the femoral vein, common iliac vein and inferior vena cava, to exclude thrombi in these regions

Prior to puncture, perform compression/duplex ultrasound of the femoral vein, common iliac vein and inferior vena cava, to exclude thrombi in these regions

Venous puncture and introduction of a 6F to 7F sheath in the femoral vein (alternatively, the median cubital vein can be used for access)

Venous puncture and introduction of a 6F to 7F sheath in the femoral vein (alternatively, the median cubital vein can be used for access)

Advancement of a balloon angiography or pigtail catheter into the pulmonary trunk

Advancement of a balloon angiography or pigtail catheter into the pulmonary trunk

Prior to contrast medium injection, measurement of the pulmonary artery and right ventricular pressure

Prior to contrast medium injection, measurement of the pulmonary artery and right ventricular pressure

Site of injection: pulmonary trunk. If this position cannot be reached or if for other reasons (suspected thrombi in the trunk) catheter manipulation in the pulmonary artery system should be avoided, the contrast medium can be injected either into the right ventricle or into the right atrium.

Site of injection: pulmonary trunk. If this position cannot be reached or if for other reasons (suspected thrombi in the trunk) catheter manipulation in the pulmonary artery system should be avoided, the contrast medium can be injected either into the right ventricle or into the right atrium.

To avoid too much of an acute volume load, with a systolic pulmonary artery pressure of > 60 mm Hg or with already manifest right ventricular failure, it is recommended to perform pulmonary angiography for both sides separately with injection of 15 to 20 mL contrast medium each with a flow rate of 10 mL/s.

To avoid too much of an acute volume load, with a systolic pulmonary artery pressure of > 60 mm Hg or with already manifest right ventricular failure, it is recommended to perform pulmonary angiography for both sides separately with injection of 15 to 20 mL contrast medium each with a flow rate of 10 mL/s.

Findings on Cardiac Catheterization

Findings on Cardiac Catheterization

Hemodynamics

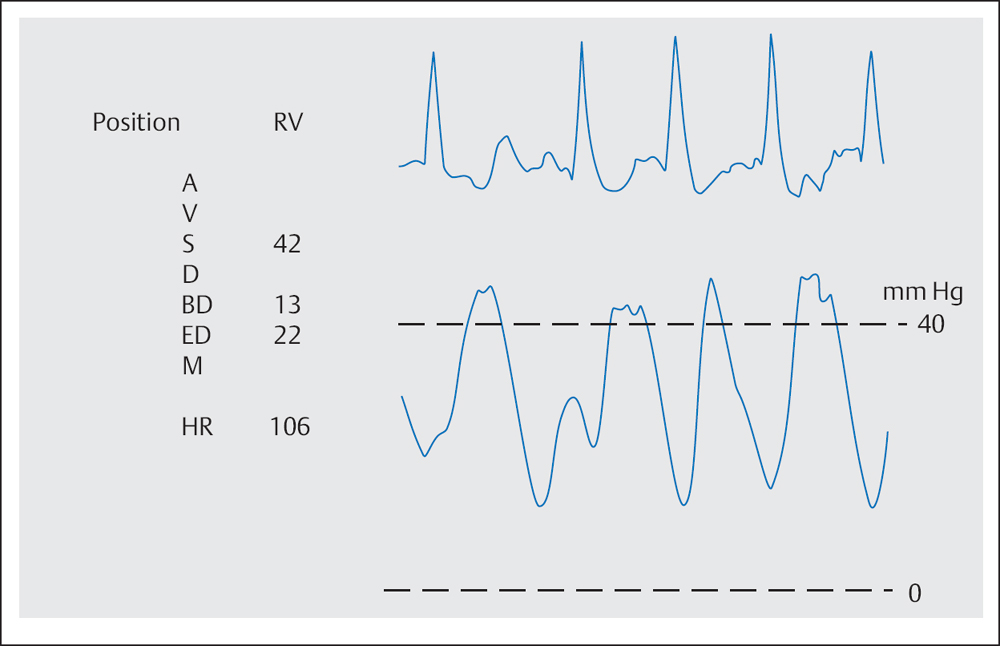

Despite having a large pulmonary embolus, the systolic PA and RV pressure may be only mildly to moderately increased in the setting of early right ventricular failure (Fig. 20.1).

Despite having a large pulmonary embolus, the systolic PA and RV pressure may be only mildly to moderately increased in the setting of early right ventricular failure (Fig. 20.1).

Pulmonary Angiography

Pulmonary Angiography

Sharply delimited complete vessel cutoffs

Sharply delimited complete vessel cutoffs

Incomplete vessel cutoff with intraluminal thrombus

Incomplete vessel cutoff with intraluminal thrombus

Retrograde contrast medium flow

Retrograde contrast medium flow

Thoracic Key

Fastest Thoracic Insight Engine