, Farouc A. Jaffer2, Marc S. Sabatine3 and Marc S. Sabatine4

(1)

Harvard Medical School Cardiology Division, Department of Medicine, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA, USA

(2)

Harvard Medical School Interventional Cardiology, Cardiology Division, Department of Medicine, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA, USA

(3)

Harvard Medical School, Boston, USA

(4)

TIMI Study Group, Cardiology Division, Departments of Medicine, Massachusetts General Hospital and Brigham & Women’s Hospital, Boston, MA, USA

Abstract

Coronary artery disease is a major cause of mortality and morbidity in the United States and worldwide. In 2010, the American Heart Association reported that 17.6 million individuals in the United States had coronary artery disease and 8.5 million had a myocardial infarction.

Abbreviations

ACC

American College of Cardiology

ACE

Angiotensin-converting enzyme

ACS

Acute coronary syndrome

ADP

Adenosine diphosphate

AHA

American Heart Association

AKI

Acute kidney injury

aPTT

Activated partial thromboplastin time

ARB

Angiotensin receptor blocker

AS

Aortic stenosis

ASA

Aspirin

AV

Atrioventricular

BMS

Bare metal stent

CABG

Coronary artery bypass graft

CAD

Coronary artery disease

CCS

Canadian Cardiovascular Society

CHF

Congestive heart failure

CP

Chest pain

CPR

Cardiopulmonary resuscitation

CVA

Cerebrovascular accident

DAPT

Dual antiplatelet therapy

DES

Drug-eluting stent

DM

Diabetes mellitus

ECG

Electrocardiogram

GIB

Gastrointestinal bleeding

GP IIb/IIIa

Glycoprotein IIb/IIIa

HR

Heart rate

HTN

Hypertension

ICH

Intracranial hemorrhage

IV

Intravenous

LBBB

Left bundle branch block

LDL-C

Low density lipoprotein cholesterol

LMWH

Low molecular weight heparin

LV

Left ventricle

LVEF

Left ventricular ejection fraction

MACE

Major adverse cardiovascular events

MI

Myocardial infarction

MR

Mitral regurgitation

NSTEMI

Non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction

NTG

Nitroglycerin

OR

Odds ratio

PAD

Peripheral arterial disease

PCI

Percutaneous coronary intervention

PMN

Polymorphonuclear neutrophil

PO

Per os

PTCA

Percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty

RV

Right ventricle

SBP

Systolic blood pressure

SC

Subcutaneous

STEMI

ST-elevation myocardial infarction

TIA

Transient ischemic attack

Tn

Troponin

UA

Unstable angina

UFH

Unfraction heparin

VSR

Ventricular septal rupture

VT

Ventricular tachycardia

Introduction

Coronary artery disease is a major cause of mortality and morbidity in the United States and worldwide. In 2010, the American Heart Association reported that 17.6 million individuals in the United States had coronary artery disease and 8.5 million had a myocardial infarction.

Diagnosis (See Table 3-1)

Table 3-1

Likelihood that signs and symptoms represent an ACS secondary to CAD

Feature | High likelihood | Intermediate likelihood | Low likelihood |

|---|---|---|---|

Any of the following: | Absence of high-likelihood features and presence of any of the following: | Absence of high- or intermediate-likelihood features but may have: | |

History | Chest or left arm pain, pressure, or tightness as chief symptom reproducing prior documented angina | Chest or left arm pain, pressure, or tightness as chief symptom | Possible ischemic symptoms in absence of any of the intermediate likelihood characteristics |

Age >70 years | |||

Known history of CAD, including MI | Male sex | Recent cocaine use | |

DM | |||

Exam | Transient MR murmur, hypotension, diaphoresis, pulmonary edema, or rales | Extracardiac vascular disease | Chest discomfort reproduced by palpation |

ECG | New, or presumably new, transient ST-segment deviation (1 mm or greater) or T-wave inversion in multiple precordial leads | Fixed Q waves | T-wave flattening or inversion <1 mm in leads with dominant R waves |

ST depression 0.5 to 1 mm or T-wave inversions >1 mm | Normal ECG | ||

Cardiac markers | Elevated cardiac TnI, TnT, or CK-MB | Normal | Normal |

History and Physical Examination (See Chap. 1)

There is often a broad range in the type of presenting pain and associated symptoms, particularly in women, older patients, young patients, diabetics, and those with renal insufficiency.

Substernal chest pain, pressure, or tightness typically occurs at rest or with increasing frequency for >20 min with often some relief to nitroglycerin. It may radiate to the neck, arms, shoulder, and/or jaws. Ischemic chest discomfort is often associated with dyspnea, diaphoresis, nausea, and/or vomiting [1–7].

Physical exam features that suggest a high likelihood of acute coronary syndrome (ACS) include diaphoresis, hypotension, transient mitral regurgitation (MR), and pulmonary edema.

Differential diagnosis of chest pain [1].

Acute coronary syndrome

Non-atherosclerotic coronary causes: dissection, spasm, embolism.

Other cardiovascular: aortic dissection, pericarditis, myocarditis, stress-mediated cardiomyopathy, pulmonary embolism, pulmonary hypertension

Gastrointestinal: esophageal (gastroesophageal reflux, esophageal spasm, esophagitis), gastric (gastritis, peptic ulcer disease), biliary (cholecystitis, cholelithiasis), pancreatitis

Musculoskeletal: trauma, costochondritis, Tietze syndrome (inflammation of costal cartilages), fibromyalgia

Pulmonary: pneumonia, malignancy, pneumothorax, pleuritis, pleural effusion

Neuropathic: herpes zoster, postherpetic neurolagia, radiation, radiculopathy

Psychiatric: panic disorder, hypochondriasis, malingering

Electrocardiogram

Normal ECG (electrocardiogram) carries a favorable prognosis but does not rule out ACS. Nearly 50 % of patients presenting with UA (unstable angina)/NSTEMI (non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction) have a normal or unchanged ECG [2].

UA/NSTEMI: new T wave inversions >0.2 mV and ≥0.05 mV ST depressions are suggestive [2].

STEMI (ST-elevation myocardial infarction): New ST elevations in ≥2 contiguous leads ≥0.2 mV in men or ≥0.15 mV in women in leads V2–V3 and/or ≥0.1 mV in other leads; new LBBB (left bundle branch block) is suggestive [6].

Posterior MI (myocardial infarction): ST depression V1 and V2 (particularly if horizontal ST depression with upright T wave and tall R wave) and/or ST elevation V7–V9 (sensitivity 57 %, specificity 98 %) [8].

Approximately 4 % of acute MI patients have isolated posterior ST elevations; detecting the presence is important since it qualifies for acute reperfusion therapy.

RV (right ventricular) MI: ST elevation ≥1 mm in V1 (sensitivity 28 %, specificity 92 %), and/or V4R (sensitivity 93 %, specificity 95 %) [9].

Cardiac Biomarkers

Cardiac troponins are the preferred biomarker in an acute ACS [1, 10].

A negative test early after symptom onset does not exclude an MI.

A negative test by 6 h after symptom onset is often sufficient to exclude an MI but if the clinical suspicion is high, the test should be repeated at 8–12 h after symptom onset [11].

High-sensitivity troponin assays: Improve early diagnosis and sensitivity particularly over the first 3 h at the potential expense of specificity (i.e. elevations due to non-ACS causes of myocyte injury) [12].

CK-MB (creatine kinase-MB) mass to CK (creatine kinase) activity ratio ≥2.5 indicates a myocardial source of CK-MB [10].

Risk Stratification

Estimating Risk

Early risk stratification, particularly in UA/NSTEMI, ensures prompt appropriate therapy. (see Table 3-2)

Table 3-2

Short-term risk of death or nonfatal MI in patients with UA/NSTEMI (ACC/AHA 2007)

Feature

High risk

Intermediate risk

Low risk

At least 1 of the following features must be present:

No high-risk features but must have 1 of the following:

No high- or intermediate-risk feature but may have any of the following features:

History

Accelerating tempo of ischemic symptoms in preceding 48 h

Prior MI, PAD, CVA, or CABG

Prior ASA use

Character of pain

Prolonged ongoing (>20 min) rest pain

Prolonged (>20 min) rest angina, now resolved, with moderate or high likelihood of CAD

Increased angina frequency, severity, or duration

Rest angina (>20 min) or relieved with rest or sublingual NTG

Angina provoked at a lower threshold

Nocturnal angina

New onset angina with onset 2 weeks to 2 months prior to presentation

New-onset or progressive CCS class III or IV angina in the past 2 weeks without prolonged (>20 min) rest pain but with intermediate or high likelihood of CAD

Clinical findings

Pulmonary edema, most likely due to ischemia

Age >70 years

New or worsening MR murmur

S3 or new/worsening rales

Hypotension, bradycardia, tachycardia

Age >75 years

ECG

Angina at rest with transient ST-segment changes >0.5 mm

T wave changes

Normal or unchanged ECG

Bundle-branch block, new or presumed new

Pathological Q waves or resting ST-depression <1 mm in multiple lead groups

Sustained VT

Cardiac markers

Elevated cardiac TnT, TnI, or CK-MB

Slightly elevated cardiac TnT, TnI, or CK-MB

Normal

Risk-stratification models such as TIMI (see Table 3-3), GRACE, or PURSUIT models may be helpful in assisting with management strategies [13].

Table 3-3

TIMI risk score (UA/NSTEMI)

Risk factor (each worth 1 point)

Age ≥65 years

≥3 CAD risk factors

Known CAD (stenosis ≥50 %)

ASA use in past 7 days

≥2 anginal episodes within past 24 h

ST segment deviation ≥0.5 mm

Elevated cardiac biomarkers

UA/NSTEMI acute coronary syndromes with increased risk (ie TIMI risk score ≥3), particularly those with ST depressions and/or elevated cardiac biomarkers, should be managed with an initial invasive approach (See section “Initial Conservative vs Invasive Strategy”) [2, 3, 7].

General Anti-ischemic Therapies

Nitrates

These agents can treat initial or recurrent angina, improve symptoms of pulmonary congestion, and decrease blood pressure in hypertensive patients.

Caution in RV MI, severe AS (aortic stenosis), hypovolemia; contraindicated if concomitant phosphodiesterase inhibitor use [1].

Beta Blockers

There is limited data for use in UA/NSTEMI but there is clear benefit in STEMI, recent MI, non-decompensated CHF (congestive heart failure), and stable angina so oral beta-blockers are recommended for all ACS unless there are clear contraindications (e.g. bradycardia, marked first or second degree AV block, active wheezing, signs of congestive heart failure or low-output state, or increased risk for cardiogenic shock (including SBP [systolic blood pressure] <100 mmHg, HR [heart rate] <60 bpm or >110 bpm, age >70years, or delayed presentation) [2–6, 14].

Intravenous beta blockers may be used in hypertensive patients without contraindications.

Caution in the setting of cocaine toxicity.

Calcium Channel Blockers

Unstable Angina/NSTEMI (See Fig. 3-1)

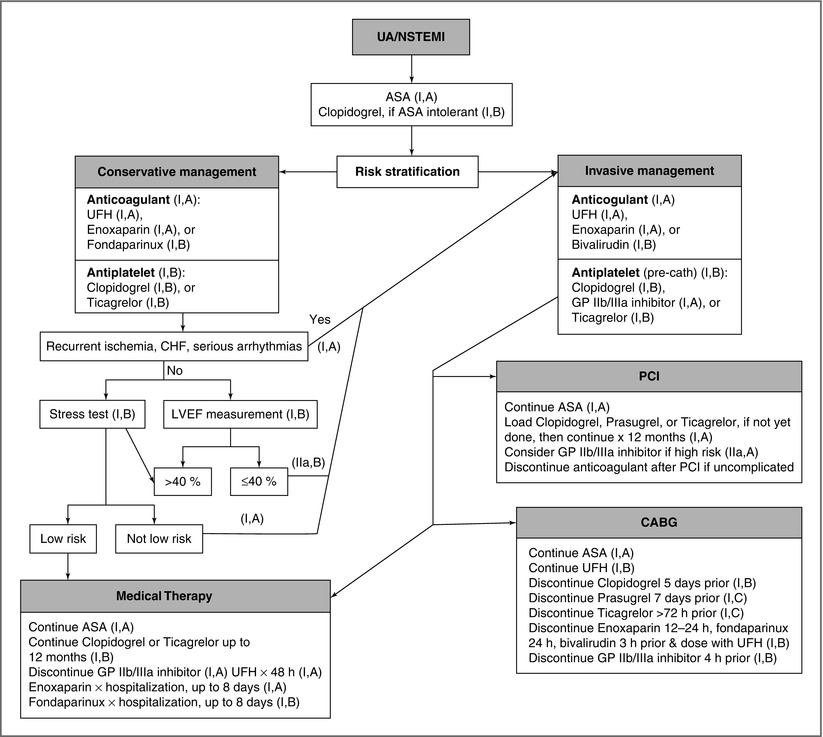

Figure 3-1

Algorithm for UA/NSTEMI management. Risk stratification assists in determining the major branchpoint is management strategy. Regardless of strategy, dual antiplatelet therapy in addition to an anticoagulant is recommended. Patients who are initially managed conservatively should undergo further non-invasive testing for additional risk stratification then referred for angiography if indicated and appropriate

Initial Conservative vs Invasive Strategy

An initial conservative strategy involves maximizing medical therapy with anticoagulation, antiplatelets, beta-blockers, and nitrates and, if patients remain symptom-free, exercise testing is performed. Coronary angiography is limited to patients with persistence of symptoms, symptom recurrence, high risk stress test features, or systolic dysfunction [2, 3, 7].

An initial invasive strategy involves the same initial maximal medical therapy with prompt catheterization once the patient has stabilized, with revascularization as appropriate [2, 3, 7, 18].

An initial invasive is recommended in patients with intermediate to high risk of recurrent events (i.e. those with recurrent angina/ischemia, elevated cardiac biomarkers, new ST segment depression, CHF or new/worsening MR [mitral regurgitation], hemodynamic instability, sustained VT [ventricular tachycardia], LVEF [left ventricular ejection fraction] < 0.40, PCI [percutaneous coronary intervention] within 6 months, or high risk score) barring contraindications.

For patients at high risk for clinical events, angiography within 24 h appears to be acceptable and others may go in 2–3 days unless there is a clinical change [18–20].

Antiplatelet Drugs

Aspirin

ADP (Adenosine Diphosphate) Receptor Blockers

An agent in this class should be given in addition to ASA regardless of whether the patient is medically managed or undergoes PCI. Given the risk of CABG (coronary artery bypass graft surgery)-related and non-CABG-related bleeding, the decision for ADP receptor blocker administration prior to coronary angiography must be weighed by the likelihood of emergency CABG and risk of bleeding [1, 3, 6, 7].

Clopidogrel

Loading with 300 mg then administering 75 mg daily along with ASA results in a 20 % reduction in MACE by 9 months, with effects as early as 24 h [24, 25].

Compared to a 300 mg loading dose, a 600 mg loading dose achieves the greatest antiplatelet activity within 2-3 h and is recommended if angiography and revascularization is planned that day [7].

In CURRENT-OASIS 7, double-dose clopidogrel (600 mg load, 150 mg daily × 7 days, then 75 mg daily) compared to standard dosing in those undergoing PCI resulted in a decrease in MI and stent thrombosis but an increase in bleeding [22].

In medically treated patients, clopidogrel should be administered for at least 1 month, and ideally 12 months.

In PCI patients, clopidogrel should be administered for at least 12 months; 1 month is mandatory for BMS (bare metal stent) but 12 months is still preferred in the setting of the recent ACS.

In patients undergoing CABG, clopidogrel should be held for at least 5 days prior to surgery.

Although 20–25 % of patients are resistant to standard clopidogrel doses, optimal clopidogrel dosing based on individual genotyping and platelet reactivity testing has not yet been established, although studies show poorer outcomes in those with clopidogrel-resistance.

Prasugrel

This agent has a more rapid onset of action with higher levels of platelet inhibition and more reliable inhibition compared to clopidogrel [1].< div class='tao-gold-member'>Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree