Above-Knee Amputation—No Profunda Inflow

Presentation

A 59-year-old male with a history of type II diabetes, hypertension, and a 40 pack-year smoking history presents with 2 months of increasing left forefoot pain and numbness. On further questioning, he provides a history of previous left external iliac and superficial femoral artery (SFA) stent placement, performed 10 years ago for symptoms of lifestyle-limiting claudication. Four years ago, he had return of his claudication, and workup revealed both stents to be occluded. Following a failed attempt at medical management, he underwent a right common femoral to left profunda femoral bypass using prosthetic graft. On examination today, his left foot demonstrates dependent rubor with no ulcerations. Pulse exam reveals a 3+ (out of 4) right femoral pulse and no left femoral, popliteal, or pedal pulses.

Differential Diagnosis

In a patient with a previous history of multilevel peripheral arterial occlusive disease, multiple previous interventions, and new onset of foot pain, critical limb ischemia should be entertained as the primary diagnosis. The presence of dependent rubor and an absent femoral pulse in the affected limb further supports this diagnosis. Alternate etiologies such as lumbar radiculopathy or diabetic neuropathy should be considered if the subsequent workup fails to support arterial occlusive disease as the underlying pathology.

The presence of a right femoral pulse and lack of left femoral pulse suggest thrombosis of the femorofemoral bypass graft as the initiating event for the left foot rest pain. Compromised right iliac inflow and left profunda femoral outflow are the most likely reasons for failure of the graft, but the normal right femoral pulse suggests a primary outflow problem. In this scenario, compromised outflow can result from intimal hyperplasia at the distal anastomosis or progressive atherosclerosis of the distal profunda branches, which in combination leads to reduced flow rates and graft thrombosis. Diabetes is frequently associated with diffuse, multifocal occlusive disease in the profunda femoral artery, and this may have contributed to the early graft failure observed in this patient.

Case Continued

Ankle-brachial indices (ABIs) were performed and show mild right and severe left leg ischemia, with an ABI of 0.78 on the right and 0.12 on the left. Segmental pressures demonstrate a greater than 25 mm Hg pressure drop in both the aortoiliac and femoropopliteal segments in the left leg, confirming multilevel occlusive disease.

Workup

Both conventional two-dimensional angiography and cross-sectional imaging (i.e., computed tomography [CT] or magnetic resonance [MR] angiography) are viable options as the next step in the evaluation. However, with the patient’s severe occlusive disease, contrast delivery via an indwelling arterial catheter may be problematic, and cross-sectional imaging offers the best option for surveying the patient’s complex anatomy following multiple failed revascularization attempts. While CT angiography (CTA) generally offers more consistent, less operator-dependent imaging and MRA offers the potential to avoid nephrotoxic agents, both studies provide similar information. Most commonly, local expertise has identified CT or MR imaging as the primary modality of choice, and this knowledge should be leveraged in these selections.

Return to Scenario

The current patient has normal renal function, and a CT angiogram is performed (Fig. 1). Notable findings include (1) a patent right and occluded left common and external iliac arteries; (2) occlusion of the femorofemoral bypass graft; (3) occlusion of the SFA in the midthigh, at the site of previous stent placement; (4) profunda femoral artery occlusion; (5) patent left popliteal artery; and (6) poor contrast delivery to the left tibial arteries that preclude accurate interpretation.

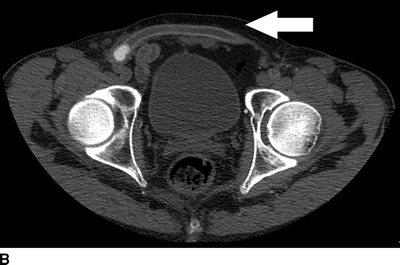

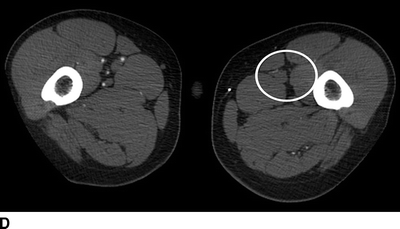

FIGURE 1 CT angiogram performed upon initial presentation. A: Occlusion of a previously stented left common femoral artery (arrow). B: Occlusion of a femoral to femoral artery bypass graft (arrow). C: Occlusion of the left profunda femoral artery at the level of the femoral bifurcation. D: Occlusion of the left profunda femoral artery in the midthigh.

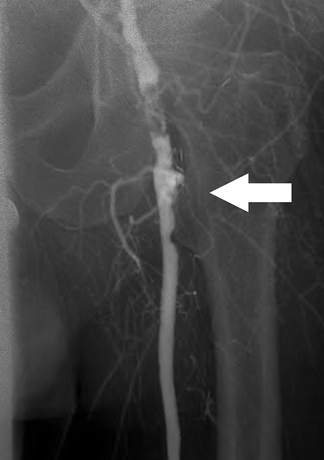

To further define the left profunda and tibial anatomy, the patient undergoes a digital subtraction arteriogram of the left leg, via a retrograde right femoral approach (Fig. 2). Contrast is injected at multiple locations along the thoracic and abdominal aorta to maximum opacification. Consistent with the CT scan, the left profunda femoral artery is occluded to the midthigh, where the primary profunda branch is noted to be diminutive. The popliteal artery is patent, but all three tibial arteries occlude in the midcalf, with no evidence of pedal artery reconstitution.

FIGURE 2 Angiogram demonstrates occlusion of the proximal profunda femoral artery (arrow).

Diagnosis and Treatment

The patient presents with acute or chronic left leg ischemia, resulting from thrombosis of the femorofemoral bypass graft. The severity of his ischemia is accentuated by occlusion of his profunda femoral artery and the corresponding loss of important collateral pathways between the common femoral and popliteal arteries. The patient’s symptoms are almost exclusively unilateral, as failed endovascular and surgical revascularization procedures have significantly accelerated the natural history of occlusive disease. This coupled with severe tibial artery atherosclerosis, which is common to many diabetic patients, has resulted in a pattern of multilevel occlusive disease that presents multiple challenges for successful revascularization.

Surgical Approach

The primary goal for successful limb salvage in this patient is restoration of inflow into the left leg. With a long-segment SFA occlusion, the profunda femoral artery needs to serve as the primary outflow target. Both the CT scan and angiogram demonstrate left profunda occlusion, although the etiology remains unclear. The pathology underlying this occlusion is the most important determinant of successful revascularization and dictates the potential for limb salvage. Intimal hyperplasia at the distal anastomosis of the femorofemoral graft and a corresponding low flow–induced thrombosis of the distal profunda would offer the best chance of success. Advanced atherosclerosis or chronic occlusive thromboemboli along the length of the profunda would significantly restrict the therapeutic options and portend a poor prognosis.

Given the extensive iliac and femoral occlusive disease, establishing inflow into the profunda is best accomplished via open surgical revascularization. An aortoprofunda bypass would offer the best durability, at the expense of increased perioperative risk. An extra-anatomic bypass, via revision of the femorofemoral bypass or a de novo left axilloprofunda bypass, would incur less perioperative risk with the trade-off of reduced long-term patency. Prosthetic grafts are traditionally the conduit of choice for inflow procedures, but large-diameter, autogenous conduit (such as femoropopliteal vein) may offer improved patency under extreme low-flow conditions. Placement of a sequential bypass from the profunda to a popliteal or tibial target may also be considered to improve outflow from a diseased or small caliber profunda.

Although a variety of surgical interventions could be reasonably defended, the patient’s relatively young chronologic age and history of multiple revascularization failures would support the procedure that offers the best long-term durability. With left iliac occlusion, left SFA occlusion, and severe left profunda femoral disease, an aorto–left profunda bypass using contralateral femoral vein would be the most reasonable solution. Critical to this plan, however, is identification of a suitable profunda femoral target. Surgical exploration will be required to determine if a profunda thrombectomy can be performed to restore continuity with the rich collateral network that bridges the femoral and popliteal vasculature. Unfortunately, extensive atherosclerosis or chronic occlusion of the mid to distal profunda is highly probable and would essentially eliminate all reasonable options for revascularization. A preoperative discussion with the patient should be undertaken to inform him of this potential outcome.

With the success of the operation intimately connected to the status of the profunda, exploration of this artery should be the initial order of business. A longitudinal incision is made in the midportion of the thigh, along the lateral border of the sartorius muscle. The sartorius muscle is retracted medially, and a plane is developed between the adductor longus (medial) and vastus intermedius (lateral) muscles. The SFA is readily visible, and dissection is continued within the intramuscular plane until the profunda femoral artery and vein are identified. Palpation of the artery reveals a firm, diffusely calcified structure with no discernable pulse or Doppler signal. A longitudinal arteriotomy is performed, and subacute thrombus, consistent with the patient’s 2-week history of rest pain, is encountered. A no. 3 embolectomy catheter is advanced proximally, but meets firm resistance at 10 cm. Withdrawal of the catheter produces thrombus but no back bleeding. Multiple attempts at proximal thrombectomy are performed with continued inability to pass the catheter beyond this occlusion. The catheter is then advanced into the distal profunda and meets firm resistance after a short distance. The arteriotomy is extended distally, and a fibrotic intraluminal cord is identified at the site of distal occlusion. Further extension of the arteriotomy fails to reveal a patent lumen. With an inability to identify a suitable distal target, the revascularization procedure is aborted. Postoperatively, the patient is informed of the operative findings and decides to delay major leg amputation at this time.

Case Continued

Over the next 3 months, the patient develops gangrene of the left first and second toes and presents for a semielective major leg amputation. Due to the relative ischemia of his calf musculature, the patient reluctantly agrees to a left above amputation. Although it is recognized that the arterial perfusion in his distal thigh is reduced, the overlying skin is warm, and the surgical team decides to proceed with an amputation at this level. At time of operation, the anterior and posterior thigh muscles are noted to be slightly pale, but viable. Although initial healing of the amputation site appears promising, the patient presents four weeks following the procedure with eschar along the incision. Continued observation over the next two weeks demonstrates progressive gangrene of the anterior flap (Fig. 3A).

FIGURE 3 A: Gangrene of an above-knee amputation stump secondary to local ischemia. B: Healing of the amputation stump following revascularization via an aorta to internal iliac artery bypass.