A nomalies of the aortic arch represent a group of lesions that may occur in isolation or in conjunction with other cardiac defects. In this chapter, aortic arch anomalies will be described as they occur in isolation. Important associations with other cardiac defects will be acknowledged. Aortic arch anomalies to be discussed in this chapter include (a) brachiocephalic branching and vascular rings (including pulmonary artery sling), (b) coarctation of the aorta, and (c) interrupted aortic arch (IAA).

ABNORMALITIES OF BRACHIOCEPHALIC BRANCHING

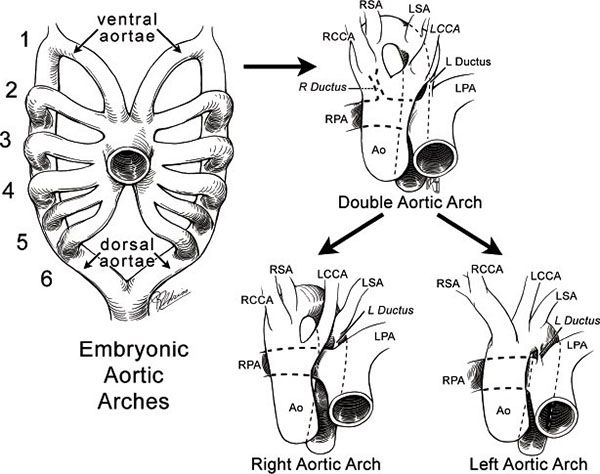

During normal development, six pairs of arches form the primitive dorsal and ventral aortae (Fig. 20.1). Most portions of the first, second, and fifth arches regress. The carotid arteries are formed by the third arches. The ventral portion of the sixth arch contributes to formation of the pulmonary artery. The right dorsal sixth arch disappears, while the left dorsal portion of the sixth arch becomes the ductus arteriosus. The subclavian arteries are formed by the seven dorsal intersegmental arteries. Involution of the right fourth arch typically results in the usual left aortic arch arrangement. A right aortic arch forms when there is involution of the left fourth arch.

Echocardiographic Assessment of the Aortic Arch

Echocardiographic imaging of the aortic arch is best achieved from the suprasternal notch views. In patients with a left aortic arch, the ascending, transverse, and descending portions of the arch, including the origins of the three arch vessels, can be imaged from the suprasternal long-axis view with the sector plane extending anteriorly from the right nipple to the left scapula posteriorly (Fig. 20.2). If the descending portion of the aorta is not visible, clockwise rotation with minimal angulation of the transducer to the right may identify the presence of a right aortic arch.

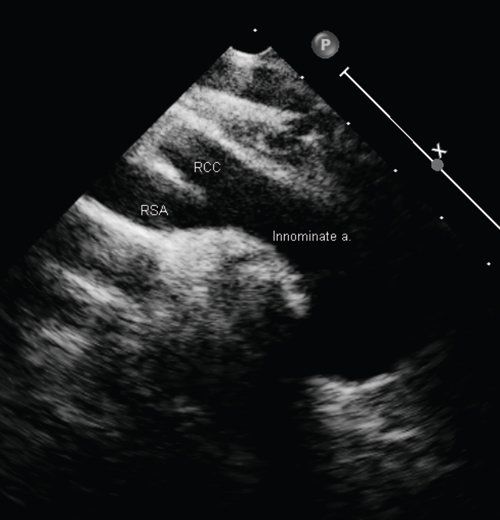

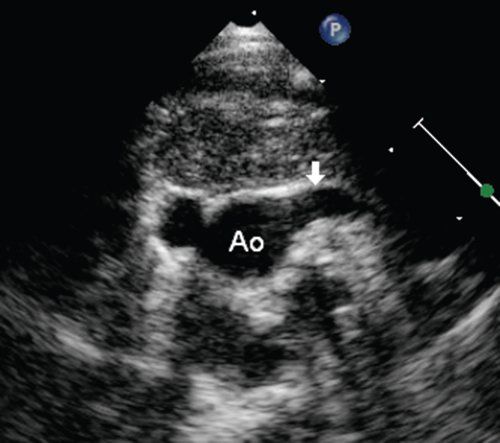

Cross-sectional imaging of the transverse aorta is obtained from the suprasternal short-axis view. Anterior angulation of the transducer allows visualization of the first brachiocephalic vessel originating from the arch, which is the innominate artery. The direction in which this vessel courses cephalad is important for determining arch sidedness. The presence of a left aortic arch is confirmed when the innominate artery courses rightward (Fig. 20.3) and the aorta descends leftward (Video 20.1). If the vessel courses leftward (Fig. 20.4) and the aorta descends rightward, a right aortic arch is present (Video 20.2). The innominate artery should be followed distally to its bifurcation into the carotid and subclavian arteries. Echocardiographic demonstration of the bifurcation of the first brachiocephalic vessel in either a left or right aortic arch confirms the absence of a vascular ring. Absence of this bifurcation in a left aortic arch suggests the presence of an aberrant right subclavian artery. A common vascular anomaly, an aberrant right subclavian artery, occurs in 0.5% of humans and carries little, if any, clinical significance (Fig. 20.5). On the other hand, absence of bifurcation of the innominate artery with a right aortic arch suggests the presence of an aberrant left subclavian artery, which has a retroesophageal course and may form a vascular ring in the presence of a left-sided ligamentum arteriosum or ductus arteriosus. Addition of color Doppler is helpful for confirming the bifurcation of the first brachiocephalic vessel.

Figure 20.1. Embryology of the aortic arches. LPA, left pulmonary artery; RPA, right pulmonary artery; RCCA, right common carotid artery; LCCA, left common carotid artery; RSA, right subclavian artery; LSA, left subclavian artery; Ao, aorta. (From Mavroudis and Backer. Pediatric Cardiac Surgery, 3rd ed. New York: Mosby; 2003.)

Figure 20.2. Suprasternal long-axis view of normal brachiocephalic branching in a left aortic arch. Asc Ao, ascending aorta; Des Ao, descending aorta; Inn, innominate artery; LCC, left common carotid artery; LSA, left subclavian artery.

Posterior tilting of the imaging plane in the suprasternal short-axis view allows determination of whether the aorta remains on the same side of the spine as it descends within the thorax. The subcostal short-axis view is also helpful for determining which side of the spine the arch is on as it crosses below the diaphragm.

Figure 20.3. Left aortic arch. Bifurcation of the innominate artery into the right common carotid artery (RCC) and right subclavian artery (RSA). The left arch is confirmed when the innominate artery courses rightward.

Another arch variant that deserves mentioning is the cervical aortic arch. Typically presenting as a pulsatile neck mass, the cervical arch extends farther into the neck than a normal arch and is best identified in the suprasternal long-axis view by moving the transducer out of the suprasternal notch and onto the neck.

Figure 20.4. Right aortic arch. The first brachiocephalic branch off the aortic arch courses leftward (arrow).

Figure 20.5. Left aortic arch with aberrant right subclavian artery (RSA) from the descending aorta. LCCA, left common carotid artery; RCCA, right common carotid artery; LSA, left subclavian artery. (From Mavroudis and Backer. Pediatric Cardiac Surgery, 3rd ed. New York: Mosby, 2003.)

VASCULAR RINGS

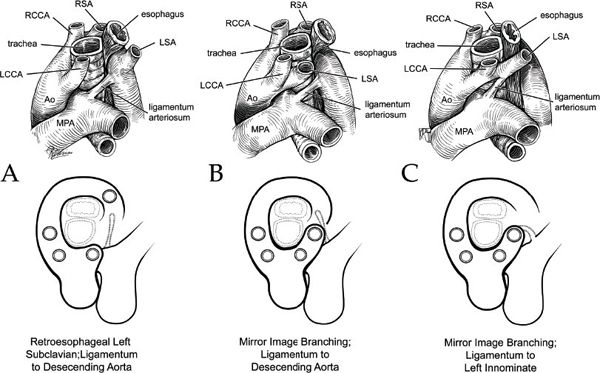

Vascular rings represent a group of vascular anomalies that cause compression of the trachea, esophagus, or both. Development of a vascular ring depends on the preservation or deletion of specific portions of the rudimentary embryonic aortic arch and may in part be formed by a patent ductus arteriosus or ligamentum arteriosum (Fig. 20.6).

Most children with vascular rings develop symptoms early, usually within the first several weeks to months of life. Symptoms may include breathing difficulty, wheezing, stridor, cough, recurrent respiratory infections, and/or dysphagia. The severity of the clinical presentation depends primarily on the degree of compression by the abnormal vessel on the trachea, bronchus, or esophagus. Respiratory symptoms are often mild and may not be apparent during the newborn period. An infant may gain appropriate weight initially because they often tolerate liquid formula without difficulty. However, once they advance to solid food, their symptoms become more evident and may include apnea or cyanosis. Patients with a double aortic arch tend to present at an earlier age than those with other types of vascular rings. Symptoms are often aggravated by crying, physical exertion, or the presence of a respiratory infection.

Figure 20.6. Right aortic arches. A: Right arch with aberrant left subclavian artery (LSA) from descending aorta. B: Right arch with left ligamentum to descending aorta. C: Right arch with left ligamentum to left subclavian artery (LSA). (From Mavroudis and Backer. Pediatric Cardiac Surgery, 3rd ed. New York: Mosby, 2003.)

Left Aortic Arch with Aberrant Right Subclavian Artery

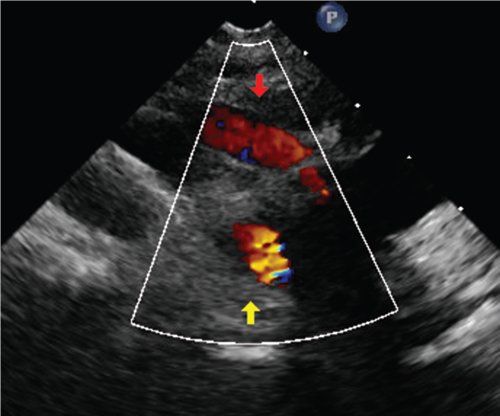

A left aortic arch with aberrant right subclavian artery is formed when there is regression of the right fourth arch, which lies between the subclavian and carotid arteries. In most cases, a left aortic arch with an aberrant right subclavian artery is not considered a clinically significant finding. However, when a right-sided ductus arteriosus or ligamentum arteriosus is present, a complete vascular ring can be formed. Inability to visualize the bifurcation of the right innominate artery originating from a left aortic arch suggests the presence of a left arch with aberrant right subclavian artery (Fig 20.7). Complete sweeps of the aortic arch from the suprasternal long- and short-axis views demonstrate the origin of the aberrant right subclavian artery from the upper descending thoracic aorta (Video 20.3). Additional imaging should focus on determining whether a right-sided ductus arteriosus is present.

Right Aortic Arch with Aberrant Left Subclavian Artery

Involution of the embryonic left fourth arch results in formation of a right aortic arch. Mirror-image branching is present in 35% of patients with a right aortic arch and occurs when there is persistence of the right fourth arch and disappearance of the left arch between the left subclavian artery and the dorsal descending aorta. A vascular ring is formed when the ligamentum arteriosum originates from the descending aorta.

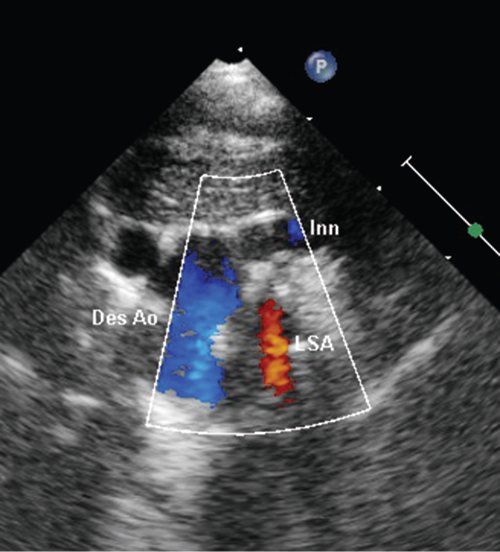

Echocardiographic identification of the first brachiocephalic vessel coursing leftward and superiorly in the suprasternal short-axis view, confirms the presence of a right aortic arch. Absence of the bifurcation of the left innominate artery with a right aortic arch suggests the presence of an aberrant left subclavian artery (Fig 20.8, Video 20.4). Additional imaging modalities may be needed to confirm the presence of a left ligamentum arteriosum.

Figure 20.7. Left aortic arch with aberrant left subclavian artery. Suprasternal notch imaging showing innominate artery coursing rightward confirming left aortic arch; but it is not bifurcating (red arrow) which suggests an aberrant right subclavian artery (yellow arrow).

Figure 20.8. Right aortic arch with aberrant right subclavian artery. Suprasternal notch imaging showing innominate artery coursing leftward (Inn) confirming right aortic arch; but it is not bifurcating which suggests an aberrant left subclavian artery (LSA). The aorta descends rightward (Des Ao).

Right Aortic Arch with Retroesophageal Segment and Left Descending Aorta

Persistence of the embryonic right fourth arch with deletion of the left arch between the left carotid and left subclavian arteries results in a right aortic arch with a retroesophageal course of the left subclavian artery (Fig. 20.6). In 65% of patients with a right aortic arch, the left subclavian artery arises from the descending aorta and courses to the left behind the esophagus. In this case, a vascular ring may be formed when there is a ligamentum arteriosum extending from the descending aorta to the left pulmonary artery.

In the suprasternal long-axis view, echocardiographic identification of this arch anomaly may be difficult because the descending aorta descends to the left despite the arch being rightward. Often associated with a cervical arch, the arch can have a hairpin appearance. The transducer may need to be moved onto the neck to accurately demonstrate branching. The diagnosis of a right aortic arch is confirmed when the first brachiocephalic vessel courses leftward and superiorly.

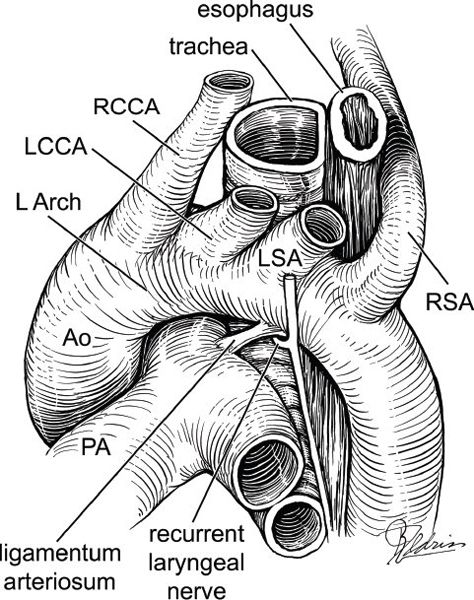

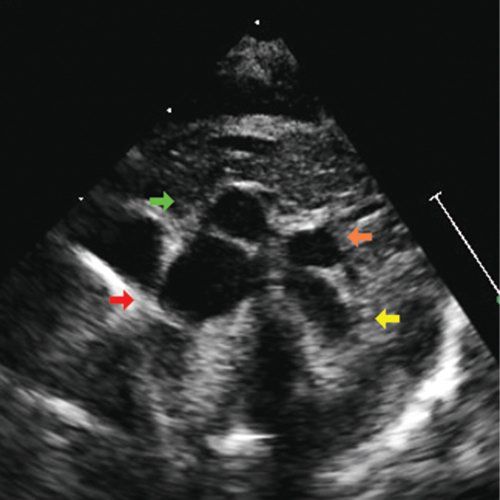

Double Aortic Arch

A double aortic arch occurs when there is persistence of both the right and left aortic arches. A ring is formed around the trachea and esophagus by the two arches, as they arise from the ascending aorta. The posterior arch is rightward and typically the dominant arch in 75% of cases, giving rise to the right carotid and subclavian arteries. The anterior, leftward arch is usually smaller and gives rise to the left carotid and subclavian arteries. In 20% of cases, the left arch may be the dominant arch, while in 5% of cases the arches may be equal in size. Approximately 20% of patients with double aortic arch have associated congenital heart disease, including tetralogy of Fallot, ventricular septal defect, coarctation, patent ductus arteriosus, transposition of the great arteries, and truncus arteriosus.

Subcostal imaging of left ventricular outflow may show bifurcation into two separate arches and is often the first clue that a double aortic arch is present. From the suprasternal long-axis view, counterclockwise rotation of the transducer will bring both arches into view (Fig. 20.9, Video 20.5). Color Doppler is helpful in confirming these findings and in identifying the origins of the arch vessels.

Pulmonary Artery Sling

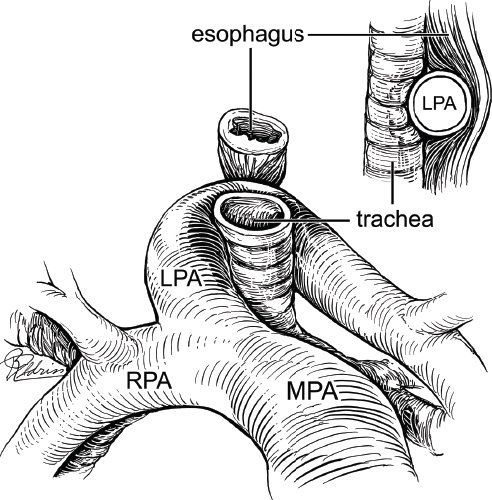

In this rare vascular malformation, the left pulmonary artery originates from the right pulmonary artery and passes between the esophagus and trachea as it courses toward the left hilum (Fig. 20.10). Symptoms are typically related to tracheal compression and include respiratory distress, stridor, cyanosis, wheezing, and retractions. Additional cardiac defects are often present and can include patent ductus arteriosus, atrial septal defect, ventricular septal defect, pulmonary atresia, left superior vena cava, and single ventricle. Tracheal stenosis, complete tracheal rings, and tracheoesophageal fistula are also common extracardiac associations.

Figure 20.9. Double aortic arch. Suprasternal notch imaging showing right aortic arch descending rightward (red arrow), smaller left aortic arch descending leftward (yellow arrow), and respective right (green arrow) and left (orange arrow) innominate arteries which will branch into common carotid and subclavian arteries.

Figure 20.10. Diagram demonstrating a pulmonary artery sling. The left pulmonary artery (LPA) originates from the right pulmonary artery (RPA) rather than the normal bifurcation from the main pulmonary artery (MPA). (From Mavroudis and Backer. Pediatric Cardiac Surgery, 3rd ed. New York: Mosby, 2003.)

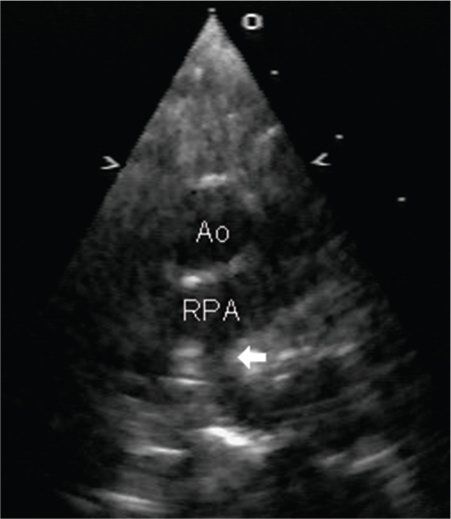

Although there may be a suggestion of an abnormal origin of the left pulmonary artery in the subcostal and parasternal short-axis views, the suprasternal long-axis view provides the best acoustic window for imaging of a pulmonary artery sling. In this view, the left pulmonary artery is seen arising from the right pulmonary artery and coursing leftward, behind the trachea to the left lung (Fig. 20.11). Color and spectral Doppler are helpful for differentiating the left pulmonary artery from other structures that may be mistaken for the left pulmonary artery, such as a patent ductus arteriosus or left atrial appendage.

Additional Imaging Modalities

The diagnosis of aortic arch anomalies such as vascular rings can often be made echocardiographically. However, because of limited acoustic windows, it may not be the dominant imaging modality used. Initial evaluation of a patient with suspected vascular ring typically includes a chest radiograph for determination of arch sidedness and its relation to the trachea. When arch sidedness is not clearly evident, the presence of a double aortic arch should be suspected. Narrowing of the trachea in the lateral images may be seen with a right aortic arch or double aortic arch (Fig. 20.12). Unilateral hyperinflation of the right lung suggests the presence of a pulmonary artery sling.

Figure 20.11. Pulmonary artery sling. Parasternal image demonstrating origin of the left pulmonary artery (arrow) from the right pulmonary artery. Ao, aorta.

The barium esophagogram has traditionally been used for the diagnosis of vascular rings. Indentation of the barium-filled esophagus by the anomalous arch vessel produces characteristic patterns for each specific lesion. For example, a right aortic arch with left ligamentum or double aortic arch produces an indentation of the posterior aspect of the esophagus (Fig. 20.13A). A double aortic arch results in bilateral compression of the esophagus in the anteroposterior view (Fig. 20.13B). A right aortic arch with a retroesophageal left subclavian artery creates an oblique indentation in the esophagus angled toward the left shoulder, whereas an aberrant right subclavian artery generates a high posterior oblique indentation of the esophagus directed from left to right. An anterior esophageal indentation is seen with pulmonary artery sling (Fig. 20.14).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree