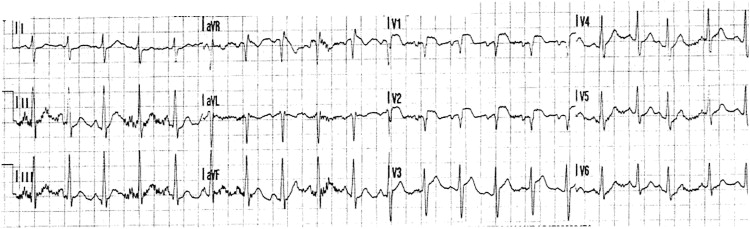

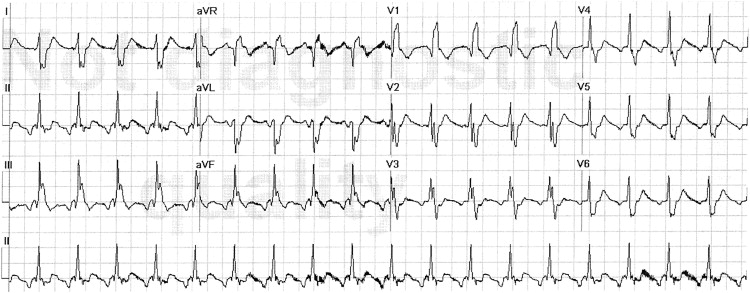

A 61-year-old man with no significant medical history suddenly developed dyspnea at rest, quickly followed by collapse. Emergency medical services found the patient in severe respiratory distress (first electrocardiogram [ECG]), and soon after, he became pulseless despite preserved sinus rhythm on the monitor, that is, pulseless electrical activity (PEA). Cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR), including intravenous epinephrine, reestablished a pulse ( Figure 1 ). A second ECG was recorded on his arrival to the emergency department. The patient had multiple subsequent episodes of PEA, with return of his pulse soon after CPR each time. He had marked jugular venous distension ( Figure 2 ).

The first ECG shows sinus tachycardia, 126 beats/min, and right-axis deviation of the QRS. ST-segment elevation, seen in leads V 1 –V 3 and aVR, is particularly prominent in leads V 1 –V 2 (3 mm), with Q waves in those 2 leads. The differential diagnosis includes both anterior wall myocardial infarction and isolated right ventricular injury from acute pulmonary emboli (PE). The latter diagnosis is suggested by right-axis deviation, ST elevation in aVR, and the ST-segment elevation being more prominent in lead V 1 than in lead V 3 , the opposite of what is characteristically seen in anterior myocardial infarction.

The second ECG shows atrial flutter with a rate of 236 flutter waves per minute, 2:1 atrioventricular conduction, complete right bundle branch block (RBBB), and right-axis deviation. The anterior ST-segment elevation and the lead V 2 Q wave have resolved. Acute RBBB is commonly seen with occlusion of the left anterior descending coronary artery proximal to the first major septal perforating branch, in which case, ST-segment elevation coincides temporally with RBBB. The lack of ST-segment elevation concurrent with the RBBB and the rapid regression of the Q wave and the ST-segment abnormality are more suggestive of PE than of myocardial infarction.

In an emergent setting, the bedside performance of transthoracic echocardiography is simple, quick, and often allows an indirect diagnosis of massive PE while ruling out other causes of PEA, such as tamponade or massive myocardial infarction. In this patient, multiple echocardiographic views showed that the left ventricle was hypercontractile, whereas the right ventricle was essentially akinetic. After 100 mg of alteplase was administered intravenously over 45 minutes as treatment for massive PE, while the circulation was maintained on a high-dose infusion of epinephrine, the patient’s systemic arterial pressure stabilized. There were no further episodes of PEA, and epinephrine was weaned off within 15 minutes of the end of the alteplase infusion. RBBB resolved. Lower extremity venous ultrasound confirmed the presence of proximal deep vein thrombosis.

The patient had already sustained multiple end-organ injuries, most notably hypoxic brain injury, and despite hemodynamic stabilization, he did not recover neurologically. Care was withdrawn 48 hours later. An autopsy was performed and confirmed the presence of bilateral pulmonary emboli with right ventricular dilatation.

Disclosures

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

See page 1473 for disclosure information.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree