Infancy

Early childhood

Late childhood

Gastroesophageal reflux

Post-viral airway hyper-responsiveness

Asthma

Infection

Asthma

Post-nasal drip

Congenital malformation

Passive smoking

Smoking

Congenital heart disease

Gastroesophageal reflux

Pulmonary tuberculosis

Passive smoking

Foreign body

Bronchiectasis

Environmental pollution Asthma

Bronchiectasis

Psychogenic cough

Definitions

Cough is defined as a forced expulsive maneuver against a closed glottis and is associated with a characteristic sound [1].

Acute cough is defined as a recent onset of cough lasting <3 weeks; chronic cough is one that lasts >8 weeks [1, 7].

Prolonged acute cough resolves over a 3- to 8-week period. An example is Pertussis cough, which may need an additional period of time to elapse before further investigations are performed.

Recurrent cough refers to repeated (>2/year) cough episodes not related to head colds, each lasting >7–14 days [8, 9]. It can be difficult to distinguish from persistent chronic cough. Most simple infective causes of cough resolve in 3–4 weeks. Children with chronic cough may require further investigations.

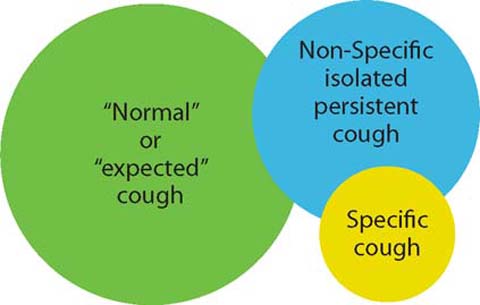

Based on the suggested etiology, cough can be categorized as “normal” or “expected” cough, specific cough, and non-specific cough (Fig. 1). “Normal” children cough 11 times a day on average, although some children experience more than 30 episodes a day, as shown in recent studies [10, 11]. Frequency and severity increase during upper respiratory tract infection, which occurs in more frequently in the pediatric age group than in adults [1, 2].

Fig 1.

Venn diagram of different types of cough

When there are symptoms and signs that point to a certain diagnosis, thus demanding further investigation, cough is defined as specific.

Acute Cough

Acute cough is most commonly caused by viral respiratory tract infections [14], which may or may not be associated with acute bronchitis. Other causes include seasonal allergic rhinitis, hay fever, an inhaled foreign body, and the first presentation of a chronic disorder.

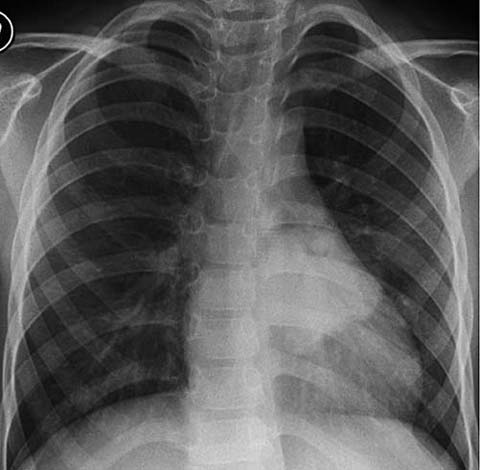

According to British Thoracic Society guidelines [1], if acute cough is due to an uncomplicated upper respiratory tract infection (absence of fever, tachypnea, and chest signs), no further investigation is needed. If an inhaled foreign body is suspected as the cause, then an urgent rigid bronchoscopy should be performed. A chest radiograph is considered when lower respiratory signs are present (Fig. 2), when there are hemoptysis, or the suggestion of a chronic respiratory disorder or when a cough is relentlessly progressive beyond 2–3 weeks.

Fig 2.

Chest X-ray showing nodular consolidation behind the heart

Chronic Cough

There may be an overlap between recurrent and chronic cough, which is why for investigation purposes these categories, along with prolonged acute cough, are not separated. Most children with chronic cough have recurrent viral bronchitis or post viral syndromes (subacute cough).

Causes of chronic cough may be classified in two groups [15]: (1) chronic isolated (no wheezing) non-specific cough in an otherwise healthy child and (2) a chronic cough in which the child has a serious underlying lung condition (Table 2).

Table 2.

Influence of pre-existing disease on the causes of cough

Chronic cough in an otherwise healthy child | Chronic cough with a significant underlying cause |

|---|---|

Recurrent viral bronchitis | Cystic fibrosis |

Post-infectious cough | Immune deficiencies |

Pertussis-like illness | Primary ciliary dyskinesia |

Cough variant asthma | Protracted bacterial bronchitis |

Allergic rhinitis, post-nasal drip and sinusitis | Recurrent pulmonary aspiration |

Psychogenic cough | Tracheoesophageal fistula, gastroesophageal reflux, hiatal hernia |

Habit (“tic” like) | Retained inhaled foreign body |

Bizarre honking cough | Tuberculosis |

Gastroesophageal reflux | Anatomical disorder (airway or lung) Interstitial lung disease |

Evaluation

Specific cough requiring further investigation is suggested by specific pointers identified in the history and clinical examination of the patient. Historical information includes time of onset, quality of cough, triggering and alleviating factors, and presence of hemoptysis (Table 3). Clinical examination pointers include digital clubbing and asymmetrical auscultatory signs.

Table 3.

Influence of the time of onset on the causes of cough

Time of onset | Neonatal, infancy and childhood |

Nature | Dry or productive |

Quality | Brassy, croupy, honking, paroxysmal, staccato |

Timing | Persistent, intermittent, nocturnal, on awaking |

Triggering factors | Cold air, exercise, feeding, seasonal, starts with a head cold |

Alleviating factors | Bronchodilators, antibiotics |

Associated symptoms | Wheezing, shortness of breath |

Two situations are commonly indicative of significant disease. The first is neonatal onset of the cough, suggesting: (a) a congenital defect leading to feeding problems and pulmonary aspiration, (b) cystic fibrosis, (c) primary ciliary dyskinesia, (d) an anatomical airways abnormality, for example a cyst compressing the airway or tracheomalacia, or (e) a chronic viral pneumonia (e.g., cytomegalovirus or Chlamydia) acquired in utero or during the perinatal period [1, 2].

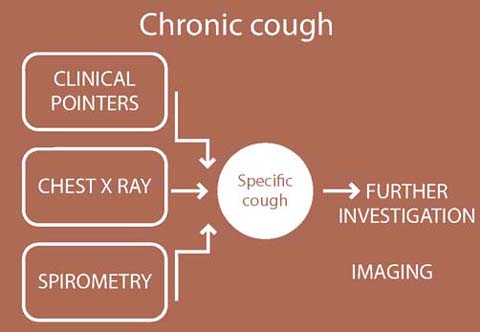

Investigation

A chest radiograph is indicated for most children with chronic cough, unless there is also a minor identified disorder, such as asthma or allergic rhinitis (Table 4). Spirometry should be always attempted in children capable of performing the maneuvers (generally those over the age of 5 years) [1, 2].

Table 4.

Imaging in a child with cough

Indication for chest X-ray | Features | Likely common diagnose |

|---|---|---|

Uncertainty about the diagnosis of pneumonia | Fever and rapid breathing Chest signs | Pneumonia |

Persisting high fever | ||

Unusual course in bronchiolitis | ||

Cough and fever persisting beyond 4–5 days | ||

Possibility of an inhaled foreign body | Choking episode may not have been witnessed Sudden onset | Inhaled foreign body X-ray may be normal |

Asymmetrical wheeze | Needs bronchoscopy | |

Hyperinflation | ||

Suggestion of a chronic respiratory disorder | Failure to thrive Finger clubbing | See Fig. 3 |

Overinflation | ||

Chest deformity | ||

Unusual clinical course | Relentlessly progressive beyond 2–3 weeks | Pneumonia |

Recurrent fever | Enlarging intrathoracic lesion | |

Tuberculosis | ||

Inhaled foreign body | ||

Lobar collapse | ||

Hemoptysis | Acute pneumonia | |

Chronic lung disorder (e.g., cystic fibrosis) | ||

Inhaled foreign body | ||

Tuberculosis | ||

Pulmonary hemosiderosis | ||

Tumor |

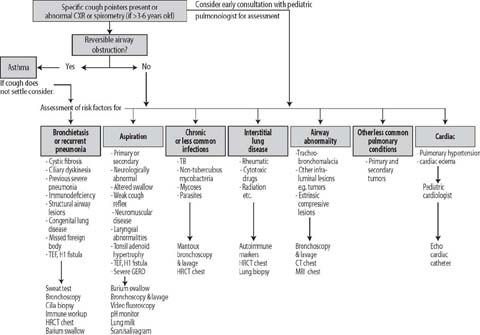

In children with a specific cough, further investigations may be warranted (Figs. 3, 4), except when asthma is the main cause [1, 2]. The next sections discuss the various etiologies of chronic cough.

Fig 3.

Flow chart illustrating the specific pathways for the investigation of children with specific cough, an abnormal chest X-ray, or abnormal spirometry. TEF, tracheoesophageal fistula; GERD, gastroesophageal reflux disease; HRCT, high-resolution computed tomography, MRI, magnetic resonance imaging

Fig 4.

Pathway for the investigation of chronic cough

Chronic Sinusitis

Sinusitis is a very common condition in children. Chronic sinusitis (lasting >3 months) involves symptoms that include nasal obstruction, nasal discharge, halitosis, and headache [16]. Although some authors report a high incidence of incidental sinus opacification in children [17], those data may be biased by different interpretations of mucosal thickening and by the true health condition of the population included in such studies [18]. Tatli et al. [18] found a 52% prevalence of moderate to severe opacification of the paranasal sinus on computed tomography (CT) in children with chronic cough, with 90% involvement of the maxillary sinuses.

Radiographs are used as a screening method for pathological conditions involving the sinuses but CT remains the imaging modality of choice for the evaluation of acute and chronic sinus inflammatory processes [19]. The association between adenoidal hypertrophy and rhinosinusitis with upper airway inflammation is increasingly recognized, with one study [20] stating that magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can document changes in adenoid size associated with the resolution of rhinosinusitis (Fig. 5). Further studies are necessary to define the role of MRI in adenoidal hypertrophy.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree