SLOW–FAST ATRIOVENTRICULAR NODAL REENTRANT TACHYCARDIA

Case presented by:

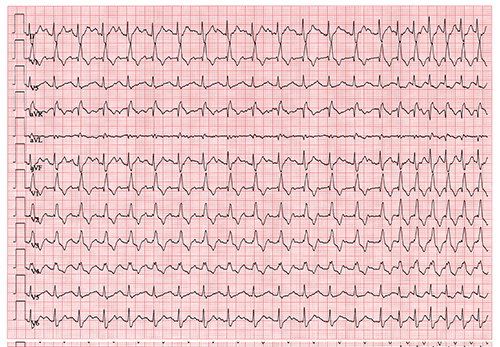

A 55-year-old man with a history of recurrent palpitation and documented tachycardia underwent an exercise stress test. His clinical tachycardia was spontaneously induced during exercise (see ECG in Figure 7.1).

Figure 7.1. Continuous 12-lead electrocardiographic recording during exercise stress test.

Question No. 1: The ECG findings most likely support which of the following tachycardias:

A.Antidromic atrioventricular (AV) reentry tachycardia.

B.Sinus tachycardia.

C.Atrioventricular nodal reentrant tachycardia (AVNRT).

D.Typical atrial flutter.ventricular tachycardia (VT).

The test was stopped, but the tachycardia continued at rest. The patient became lightheaded. Blood pressure was recorded as 95/65 mmHg.

Question No. 2. What is the best management of this recurrent tachycardia?

A.Hydrate and reassure the patient. No further treatment needed.

B.Start intravenous (IV) lidocaine and call for urgent coronary intervention.

C.Start IV diltiazem, warfarin, and plan for electrophysiology (EP) study.

D.Perform carotid sinus massage or start IV adenosine. Recommend EP study and ablation.

E.Urgent direct current cardioversion.

The tachycardia terminated with carotid sinus message. During EP study, slow–fast AVNRT was inducible with right ventricular (RV) pacing alone and not with atrial pacing.

Question No. 3. These EP study results can be explained by which of the following?

A.Antegradely, the fast-pathway effective refractory period (ERP) is longer than slow-pathway ERP.

B.Retrogradely, the fast-pathway ERP is longer than the slow-pathway ERP.

C.Antegradely, the slow-pathway ERP is longer than the fast-pathway ERP.

D.Retrogradely, the slow-pathway ERP is longer than the fast-pathway ERP.

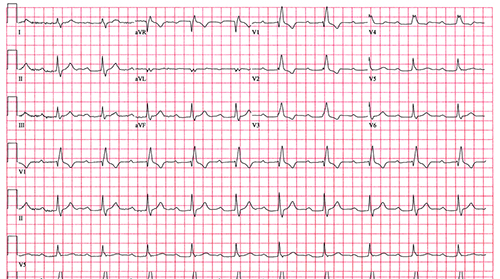

The patient’s ECG at rest is shown in Figure 7.2.

Figure 7.2. The ECG of the same patient at rest.

Question No. 4: Based on Figure 7.2 and previous ECG findings, what is the best interventional approach?

A.Pacemaker insertion with beta-blocker therapy.

B.Careful slow-pathway ablation.

C.Ablation of the fast pathway.

D.AV nodal ablation with pacemaker insertion.

Discussion

Slow–fast AVNRT, also known as typical or common AVNRT, is one of the most frequent regular narrow-complex tachycardias in normal heart. It affects patients of different ages and tends to be more frequent in women. The clinical presentation in patients with normal heart usually includes palpitations, weakness, and dizziness.

Electrocardiogram

The ECG of typical AVNRT shows long-PR, narrow-complex regular tachycardia. Since the activation of both the ventricles and the atria occur simultaneously starting from the AV junction area, it is typically difficult to discern the P waves since they are obscured by the QRS complexes. The P waves can occur at the end of the QRS also and present as a terminal delay. To better observe the P waves at the end of QRS, it is helpful to carefully compare side by side the QRS complex in lead V1 during tachycardia and sinus rhythm.

Anatomy, Physiology, and Intracardiac Electrophysiologic Studies

The anatomy of the AV node has been a subject of great debate in the EP arena and multiple models have been described. It is thought that the AV node has extensions into the atria with different conduction velocities. Typically, the slow-conducting pathway extends from the compact node in posterior direction toward the coronary sinus (CS) ostium. The fast pathway of the AV node takes a more anterior course before it connects to the compact node.

The physiology of AVNRT obeys the same electrophysiologic principles of reentry. An input into the AV node (typically premature compared to the previous inputs) blocks in the fast pathway and conducts down the slow pathway relatively slowly. Since the impulse reaches the distal end of the fast pathway as it connects to the compact node, it travels retrogradely in the fast pathway, causing a retrograde atrial activation before it turns around and reenters the slow pathway antegradely; the tachycardia is then initiated.

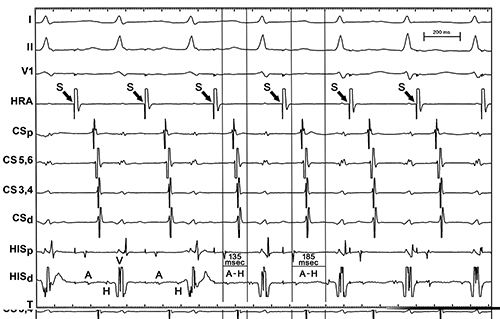

To allow the initiation of this reentry with a premature atrial complex (PAC), the antegrade ERP of the fast pathway should be higher than the ERP of the slow pathway. The block in the fast pathway and conduction down the slow pathway is seen and described as a “jump,” which proves the existence of at least two different pathways with different ERPs. It is also known as “dual physiology” of the AV node. By definition, “jump” is when the A2-H2 interval prolongs by at least 50 ms with a 10-ms decrease in A1-A2. The presence of dual physiology of the AV node can also be observed with the sudden prolongation of the AH interval by at least 50 ms, when the pacing cycle is decreased by 10 ms during incremental atria pacing (Figure 7.3). Retrograde conduction with RV pacing is relatively fast and present down to at least the cycle length of the tachycardia. However, the absence of this fast retrograde ventriculoatrial (VA) conduction at baseline does not necessarily exclude AVNRT. The tachycardia can also be initiated with RV pacing in some cases of fast retrograde VA conduction. This can be achieved with incremental RV pacing or, more likely, with premature RV stimulation.

Figure 7.3. Sudden increase in AH interval during incremental atrial pacing from high right atrium.

Often initiation of the tachycardia requires IV isoproterenol. Typically a small dose (1 µ/min) is sufficient. At times, the tachycardia is initiated only with stimulation during the washout period after stopping isoproterenol. The tachycardia can be initiated with incremental atrial pacing. Pacing should be stopped immediately once the tachycardia starts. If incremental pacing is continued and the change in activation sequence and cycle length signaling the beginning of the tachycardia is missed, the latter can be terminated with faster pacing and overdrive.

Introducing PACs during different pacing drives is another way AVNRT can be induced (Figure 7.4). Sometimes an S3

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree