A CASE OF ARRHYTHMOGENIC RIGHT VENTRICULAR DYSPLASIA

Case presented by:

Patient J.D. is a 34-year-old man who presented with syncope. His ECG in the emergency department (ED) is shown in Figure 46.1. He reports that he had just finished running 5 miles and was in his cool-down phase when he abruptly lost consciousness. He scraped his knee and hit his head when he fell. He reports about 2 seconds of lightheadedness before passing out. When he awoke, he felt well other than his head and his knee. His physical examination in the ED was normal. He was not orthostatic. Rare premature ventricular contractions (PVCs) were observed on the monitor, which demonstrated a left bundle branch block (LBBB) superior axis. The patient takes no medications. His past medical history is unremarkable. He has always been an avid runner and was a 3-season varsity athlete in high school. He also ran in college on a track scholarship. Since college, he has run 5 marathons. There is no family history of cardiac disease or sudden cardiac death (SCD). An echocardiogram obtained in the ED revealed a dilated right ventricle with reduced function, and normal left ventricular (LV) size and function.

Questions

1.Would you admit the patient or discharge him to home?

2.What is the most likely diagnosis?

3.What further testing would you advise?

4.Assuming your suspected diagnosis is confirmed, what treatment would you advise?

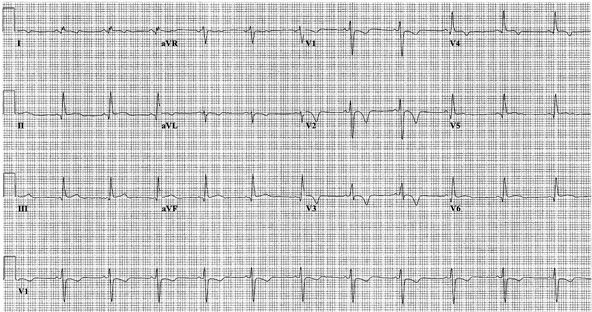

Figure 46.1 Patient’s ECG at presentation.

Discussion

Arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia (ARVD) is an inherited cardiomyopathy characterized by ventricular arrhythmias and structural abnormalities of the right ventricle. ARVD results from progressive replacement of right ventricular (RV) myocardium with fatty and fibrous tissue. The precise prevalence of ARVD in the United States has been estimated to be 1 in 5000 of the general population. Patients with ARVD typically present because of ventricular arrhythmias, syncope, or sudden death.

ARVD typically presents in young adults about 30 years of age. Diagnosis of ARVD prior to puberty is exceedingly uncommon. It is also uncommon for ARVD to initially present after the age of 50.

Diagnosis of ARVD

The diagnosis of ARVD is established based on the criteria developed by an expert writing group led by Dr. Frank Marcus. Specific cardiac tests that are recommended in all patients suspected of having ARVD include an ECG; a signal-averaged ECG (SAECG), a Holter monitor and an echocardiogram. Analysis of RV size and function can also be obtained by cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) and/or computed tomography (CT). If the results of the noninvasive tests point toward a diagnosis of ARVD, invasive testing including RV angiography, endomyocardial biopsy, and electrophysiology testing are recommended to establish the diagnosis and help provide further information to guide treatment recommendations.

Electrocardiographic Evaluation

ECG abnormalities are detected in more than 90% of ARVD patients. However, it is important to be aware that ARVD rarely can present in a patient with a totally normal ECG. The typical ECG features of ARVD are demonstrated by the ECG obtained from our patient. A diagnosing physician can appreciate the T-wave inversion (TWI) in the right precordial leads from V1 to V4. An epsilon wave is not present. This is not surprising as epsilon waves are observed in less than 5% of patients and usually in patients with advanced disease. TWI in leads V1 to V3 is the most consistent ECG finding seen in ARVD patients. The juvenile pattern of TWI in leads V1 to V3 or beyond is a normal variant in children less than 12 years of age and present in 1% to 3% of the healthy population 19 to 45 years of age, but it is present in 87% of patients with ARVD. TWI beyond V1 in a patient in the above age group who has no apparent heart disease but does have ventricular arrhythmias of LBBB morphology should raise the suspicion of ARVD. Late potentials on SAECG recordings are the counterpart of the epsilon waves and are considered a minor criterion for the diagnosis of ARVD.

Imaging of the Right Ventricle

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree