Despite significant advances in its treatment, acute myocardial infarction (AMI) remains an important cause of heart failure (HF). Contemporary data remain lacking, however, describing long-term trends in incidence rates, demographic and clinical profiles, and outcomes of patients who develop HF as a complication of AMI. Our study sample consisted of 11,061 residents of the Worcester (Massachusetts) metropolitan area hospitalized with AMI at all greater Worcester hospitals in 15 annual study periods from 1975 to 2005. Overall, 32.4% of patients (n = 3,582) with AMI developed new-onset HF during their acute hospitalization. Patients who developed HF were generally older, more likely to have pre-existing cardiovascular disease, and were less likely to receive cardiac medications or undergo revascularization procedures during their hospitalization than patients who did not develop HF (p <0.001). Incidence rates of HF remained relatively stable from 1975 to 1991 at 26% but decreased thereafter. Decreases were also noted in hospital and 30-day death rates in patients with acute HF (p <0.001). However, patients who developed new-onset HF remained at significantly higher risk for dying during their hospitalization (21.6%) than patients who did not develop this complication (8.3%, p <0.001). Our large community-based study of patients hospitalized with AMI demonstrates that incidence rates of and mortality attributable to HF have decreased over the previous 3 decades. In conclusion, HF remains a common and frequently fatal complication of AMI to which increased surveillance and treatment efforts should be directed.

In this investigation, we provide a 30-year (1975 to 2005) perspective into changing trends in the incidence rates of heart failure (HF), hospital treatment practices, and short-term death rates associated with HF complicating acute myocardial infarction (AMI).

Methods

The Worcester (Massachusetts) Heart Attack Study is a population-based investigation examining long-term trends in the incidence and death rates of greater Worcester (2000 census 478,000) residents hospitalized with AMI at all metropolitan Worcester medical centers. Methods used in this study have been previously described. Patients with possible AMI were identified through review of computerized hospital databases for patients with discharge diagnoses consistent with possible AMI or coronary heart disease-related rubrics. Trained study physicians and nurses individually reviewed medical records of all geographically eligible patients in a standardized manner. Diagnosis of AMI was confirmed according to pre-established criteria and patients were included in the study if they met ≥2 of 3 predefined criteria. Autopsy-proved cases of AMI were included in the sample, irrespective of other criteria. Patients with perioperative or trauma-related AMI were not included.

Our study population consisted of 11,061 patients without a history of HF who developed a validated AMI at all hospitals in the Worcester metropolitan area during the 15 study years of 1975 (n = 680), 1978 (n = 722), 1981 (n = 830), 1984 (n = 609), 1986 (n = 642), 1988 (n = 589), 1990 (n = 641), 1991 (n = 702), 1993 (n = 772), 1995 (n = 786), 1997 (n = 849), 1999 (n = 766), 2001 (n = 947), 2003 (n = 874), and 2005 (n = 652).

Study physicians and nurses abstracted clinical and demographic data from medical records of patients with confirmed AMI. Abstracted data included patient’s age, gender, race, medical history, AMI order (initial vs previous), type of AMI (Q wave vs non-Q wave), physiologic factors (e.g., blood pressure), laboratory measurements (e.g., serum total cholesterol, glucose), length of hospital stay, presenting symptoms, and discharge status. Use of cardiac medications, thrombolysis, cardiac catheterization, intra-aortic balloon counterpulsation, percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), and coronary artery bypass surgery and development of important clinical complications were determined by trained reviewers using pre-established criteria. Patients with a medical history of HF were excluded. New-onset HF was considered present if a patient was described in his/her medical record as having clinical or radiographic evidence of pulmonary edema or bilateral basilar rales with an S 3 gallop on admission or at any time during his/her hospitalization. Survival status after hospital discharge was determined through review of hospital medical records and search of death certificates and Social Security files for residents of the Worcester metropolitan area. Follow-up after discharge was obtained for >99% of discharged patients.

Differences in demographic and clinical characteristics as well as in the receipt of various treatment practices among AMI patients who did and did not develop new onset HF were examined using chi-square-tests for discrete variables and Student’s t-test for continuous variables. Similar methods were used to compare differences between those with HF who survived, compared with those who did not survive, to hospital discharge. Short-term prognosis was examined in each study year and overall by calculating in-hospital and 30-day case fatality rates (CFRs) separately for patients who did and those who did not develop HF.

Multivariate logistic regression modeling was used to evaluate the influence of potential confounding and/or mediating factors on the odds of developing HF. We examined the relation of incident HF to the following factors: age, gender, AMI type, AMI order, body mass index, history of stroke, hypertension, diabetes, and angina, hospital development of complete heart block, atrial fibrillation, stroke, and cardiogenic shock, and hospital survival status. Although body mass index and estimated glomerular filtration (eGFR) rates differed among our respective comparison groups, these variables were not included in our multivariable adjusted models because information about these factors was missing in a large percentage of hospitalized patients. Multivariable logistic regression analyses were also used to assess overall effect of HF on in-hospital and 30-day mortalities and control for similar potentially confounding prognostic factors.

Changes over time in incidence rates of HF complicating AMI and in-hospital and 30-day post-admission CFRs were examined using Mantel-Haenszel chi-square test for trends. Logistic regression models controlling for previously described covariates were used to examine differences in incidence rates of HF and short-term CFRs in those with HF during the 30-year period under study.

Results

In total 11,061 greater Worcester residents without previously diagnosed HF were hospitalized with confirmed AMI from 1975 to 2005. The sample was elderly and predominantly Caucasian, with a high prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors ( Table 1 ). Thirty-two percent of patients (n = 3,582) developed a first episode of HF during their hospitalization for AMI.

| Characteristic | Total Sample | Patients Hospitalized in 2001, 2003, and 2005 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HF Present (n = 3,582) | HF Absent (n = 7,479) | p Value | HF Present (n = 702) | HF Absent (n = 1,770) | p Value | |

| Age (years), mean ± SD | 71.7 ± 12.4 | 64.9 ± 14.0 | <0.001 | 75.5 ± 12.1 | 66.9 ± 14.5 | <0.001 |

| Age (years) | ||||||

| <55 | 9.6% | 23.4% | — | 6.6% | 23.0% | — |

| 55–64 | 17.0% | 24.1% | — | 12.5% | 20.8% | — |

| 65–74 | 28.3% | 25.6% | — | 22.1% | 21.5% | — |

| 75–84 | 30.7% | 19.5% | — | 34.1% | 23.0% | — |

| ≥85 | 14.5% | 7.5% | <0.001 | 24.8% | 11.7% | <0.001 |

| Men | 54.4% | 65.1% | <0.001 | 47.9% | 62.4% | <0.001 |

| Race | ||||||

| White | 96.7% | 94.6% | <0.001 | 91.3% | 90.5% | 0.53 |

| Other | 3.4% | 5.4% | <0.001 | 8.7% | 9.5% | 0.46 |

| Body mass index (kg/m 2 ) | ||||||

| <25 | 37.6% | 33.1% | — | 34.1% | 30.7% | — |

| 25–29.9 | 35.5% | 38.6% | — | 35.3% | 39.3% | — |

| ≥30 | 27.1% | 28.3% | 0.002 | 30.5% | 30.0% | 0.46 |

| Pre-existing conditions | ||||||

| Angina pectoris | 25.1% | 21.2% | <0.001 | 17.7% | 17.8% | NS |

| Diabetes mellitus | 30.3% | 21.4% | <0.001 | 35.9% | 25.2% | <0.001 |

| Hypertension | 59.3% | 52.7% | <0.001 | 74.5% | 66.2% | <0.001 |

| Stroke | 11.9% | 6.3% | <0.001 | 14.7% | 7.9% | <0.001 |

| Acute presenting symptoms | ||||||

| Chest pain ⁎ | 64.9% | 81.3% | <0.001 | 64.0% | 81.8% | <0.001 |

| Diaphoresis ⁎ | 35.5% | 42.9% | <0.001 | 32.1% | 42.1% | <0.001 |

| Dyspnea ⁎ | 67.9% | 47.9% | <0.001 | 68.0% | 51.0% | <0.001 |

| Acute myocardial infarction type | ||||||

| Initial | 65.8% | 74.4% | <0.001 | 67.7% | 74.5% | <0.001 |

| Q wave | 48.7% | 43.9% | <0.001 | 24.2% | 24.0% | <0.001 |

| Clinical complications | ||||||

| Third-degree heart block | 6.1% | 3.3% | <0.001 | 2.8% | 2.6% | 0.78 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 24.8% | 10.9% | <0.001 | 29.3% | 15.6% | <0.001 |

| Cardiogenic shock | 12.5% | 3.3% | <0.001 | 12.5% | 2.0% | <0.001 |

| Stroke † | 1.3% | 1.1% | 0.32 | 2.3% | 1.7% | 0.38 |

| Physiological findings at time of hospital admission, mean ± SD | ||||||

| Systolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 142.9 ± 35.2 | 143.4 ± 32.6 | 0.66 | 142.0 ± 35.9 | 143.0 ± 33.0 | 0.48 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 77.5 ± 21.9 | 79.6 ± 19.7 | 0.005 | 75.9 ± 21.7 | 79.0 ± 19.9 | <0.001 |

| Heart rate (beats/min) † | 91.3 ± 25.7 | 81.5 ± 21.8 | <0.001 | 92.8 ± 26.1 | 82.9 ± 21.7 | <0.001 |

| Laboratory findings at time of hospital admission (mg/dl), mean ± SD | ||||||

| Serum glucose § | 201.0 ± 124.8 | 168.8 ± 133.6 | <0.001 | 199.6 ± 137.8 | 168.2 ± 161.5 | <0.001 |

| Estimated glomerular filtration rate findings (%) § | 56.1 ± 23.3 | 69.0 ± 26.3 | <0.001 | 53.3 ± 22.0 | 67.0 ± 25.6 | <0.001 |

| Serum cholesterol | 209.0 ± 61.7 | 210.1 ± 56.0 | 0.050 | 176.7 ± 60.2 | 181.5 ± 49.3 | 0.12 |

| Serum hemoglobin | 13.3 ± 4.2 | 14.0 ± 3.3 | <0.001 | 13.2 ± 5.5 | 14.0 ± 4.2 | <0.001 |

† 1986 to 2005 only, ‡ 1991 to 2005 only; and

Patients who developed new-onset HF were on average older, more frequently women, and were more likely to have previous MI, diabetes, angina, hypertension, and stroke than patients who did not develop this complication ( Table 1 ). Patients with HF complicating AMI were also more likely to have developed atrial fibrillation, complete heart block, and cardiogenic shock during their hospitalization. Patients with HF had lower diastolic blood pressure, lower total serum cholesterol levels, lower hemoglobin levels, and a lower eGFR rate, but higher heart rates and blood glucose levels on hospital admission than patients who did not develop HF. In contrast to patients admitted during earlier study years, patients with HF admitted in 2001, 2003, and 2005 did not differ from those who did not develop HF with respect to history of angina, total serum cholesterol levels, body mass index, or likelihood of developing complete heart block during their index hospitalization.

Patients who developed new-onset HF were less likely to be treated with aspirin, β blockers, thrombolytics, and lipid-lowering agents during their hospitalization for AMI than patients who did not develop HF (p <0.001 for all comparisons; Table 2 ). Compared to those who did not develop HF, patients with HF complicating AMI were more likely to be prescribed calcium channel blockers and an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor or angiotensin receptor blocker during their hospitalization (p <0.001 for the 2 comparisons). Patients with incident HF were less likely to have undergone cardiac catheterization or PCI but were more likely to have undergone placement of an intra-aortic balloon pump (p <0.001).

| Total Sample | Patients Hospitalized in 2001, 2003, and 2005 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HF Present | HF Absent | p Value | HF Present | HF Absent | p Value | |

| (n = 3,582) | (n = 7,479) | (n = 702) | (n = 1,770) | |||

| Medications | ||||||

| Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor or angiotensin receptor blocker | 56.2% | 38.2% | <0.001 | 68.4% | 62.6% | 0.007 |

| Aspirin | 58.8% | 68.3% | <0.001 | 92.0% | 93.3% | 0.24 |

| β Blockers | 53.2% | 69.2% | <0.001 | 88.3% | 92.0% | 0.004 |

| Calcium channel blockers † | 39.3% | 34.9% | <0.001 | 27.8% | 21.3% | <0.001 |

| Lipid-lowering agents ‡ | 24.1% | 33.3% | <0.001 | 65.4% | 71.9% | 0.002 |

| Thrombolytics ‡ | 16.2% | 20.6% | <0.001 | 5.4% | 7.3% | 0.097 |

| Procedures | ||||||

| Cardiac catheterization | 27.7% | 37.2% | <0.001 | 53.1% | 69.4% | <0.001 |

| Coronary artery bypass graft surgery ⁎ | 4.2% | 4.5% | 0.58 | 7.0% | 7.3% | 0.79 |

| Percutaneous coronary intervention ‡ | 16.3% | 24.9% | <0.001 | 33.3% | 50.7% | <0.001 |

| Intra-aortic balloon counterpulsation | 6.8% | 2.9% | <0.001 | 12.8% | 4.4% | <0.001 |

Irrespective of HF status, patients hospitalized with AMI during the 3 most recent study years were more likely to have received effective cardiac medications and were more likely to have undergone cardiac catheterization, PCI, and intra-aortic balloon placement than patients hospitalized with AMI during early study years ( Table 2 ). Prescribing of thrombolytic medications decreased during recent years in the 2 study groups. Differences in the use of various treatment practices between patients who did and did not develop HF during recent study years were similar to those observed over the 30-year study period, with the exception of aspirin prescription, which did not differ between our 2 primary comparison groups during the most recent study years.

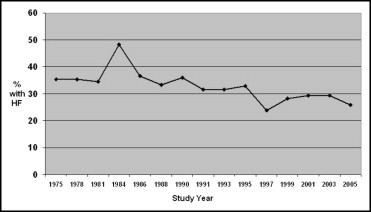

Incidence rates of HF complicating AMI decreased significantly over the 30-year study period (p <0.01). From 1975 to 1990, the proportion of patients who developed HF remained relatively stable at approximately 35% ( Figure 1 , Table 3 ). Beginning in 1991, incidence rates of acute HF began to decrease, reaching lows of 23.8% in 1997 and 25.8% in 2005. Compared to patients hospitalized in 1975, patients admitted from 1991 to 2005 had a lower unadjusted odds of developing HF ( Table 3 ). Results were qualitatively similar for models adjusting for important demographic and clinical factors ( Table 3 ).

| Study Year | Patients | Developing HF | Age- and Gender-Adjusted Odds of Developing HF | Multivariable Adjusted Odds of Developing HF ⁎ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1975 | 680 | 35.4% | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| 1978 | 722 | 35.3% | 0.95 (0.76–1.20) | 0.91 (0.72–1.15) |

| 1981 | 830 | 34.5% | 0.84 (0.68–1.05) | 0.83 (0.66–1.04) |

| 1984 | 609 | 48.3% | 1.66 (1.31–2.09) | 1.59 (1.25–2.03) |

| 1986 | 642 | 36.5% | 0.92 (0.73–1.16) | 0.89 (0.70–1.13) |

| 1988 | 589 | 33.3% | 0.77 (0.61–0.99) | 0.73 (0.57–0.94) |

| 1990 | 641 | 36.0% | 0.85 (0.67–1.07) | 0.85 (0.67–1.08) |

| 1991 | 702 | 31.6% | 0.71 (0.56–0.89) | 0.69 (0.54–0.88) |

| 1993 | 772 | 31.6% | 0.69 (0.55–0.87) | 0.68 (0.54–0.86) |

| 1995 | 786 | 32.9% | 0.74 (0.59–0.93) | 0.73 (0.58–0.92) |

| 1997 | 849 | 23.8% | 0.44 (0.35–0.56) | 0.44 (0.35–0.56) |

| 1999 | 766 | 28.2% | 0.57 (0.46–0.72) | 0.57 (0.45–0.73) |

| 2001 | 947 | 29.3% | 0.56 (0.45–0.69) | 0.55 (0.44–0.70) |

| 2003 | 874 | 29.4% | 0.57 (0.46–0.71) | 0.57 (0.45–0.72) |

| 2005 | 652 | 25.8% | 0.47 (0.37–0.60) | 0.46 (0.35–0.60) |

⁎ Adjusted for patient’s age, gender, and history of angina, hypertension, diabetes, or stroke, acute myocardial infarction order, acute myocardial infarction type, and development of complete heart block, atrial fibrillation, and cardiogenic shock during hospitalization.

Because decreasing rates of new-onset HF complicating AMI were noted contemporaneously with changes in the proportion of patients developing a Q wave or an initial AMI over time, and because these factors are known to relate to extent of myocardial injury, we examined changes over the period under study in incidence rates of HF separately for patients with Q-wave versus non–Q-wave AMI and for patients with an initial versus previous AMI. Results of these analyses revealed similar trends to those noted in the overall study sample. For example, from 1975 to 1990, the proportion of patients with a Q-wave MI who developed HF was 38.1% compared to 35.1% in patients with a non–Q-wave AMI. Beginning in 1991, incidence rates of HF decreased in the 2 groups reaching rates of 27.9% and 25.2%, respectively, in 2005.

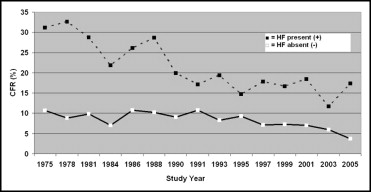

Overall, 21.6% of patients with AMI who developed HF died during their acute hospitalization compared to 8.3% of those who did not develop this complication (p <0.001). In multivariate models adjusting for previously described demographic, medical history, and clinical factors known to be associated with increased mortality from AMI ( Figure 2 ), development of HF was associated with a two-fold higher odds (odds ratio 1.99, 95% confidence interval 1.73 to 2.28) of dying during hospitalization for AMI. Results remained similar and statistically significant in multivariable adjusted analyses restricted to patients hospitalized at all metropolitan Worcester medical centers during our 3 most recent study years (odds ratio 1.84, 95% confidence interval 1.32 to 2.56).

Hospital CFRs in patients with HF decreased over the 30-year study period ( Figure 2 , Table 4 ). After controlling for previously described demographic and clinical factors ( Table 2 ), adjusted odds of dying in patients with HF decreased for each study year (with the exception of 1978) compared to 1975 ( Table 4 ). Similar to decreasing hospital CFRs, the proportion of patients with HF who died within 30 days of hospitalization decreased significantly over time, from 29.1% in 1975 to 16.0% in 2003 (p <0.001).

| Study Year | Patients | Hospital CFRs | Age- and Gender-Adjusted Odds of Dying | Multivariable Adjusted Odds of Dying ⁎ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1975 | 241 | 31.1% | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| 1978 | 255 | 32.6% | 1.01 (0.69–1.49) | 0.89 (0.58–1.36) |

| 1981 | 286 | 28.7% | 0.78 (0.53–1.14) | 0.70 (0.46–1.06) |

| 1984 | 294 | 21.8% | 0.58 (0.39–0.86) | 0.54 (0.35–0.83) |

| 1986 | 234 | 26.1% | 0.66 (0.44–0.99) | 0.59 (0.37–0.93) |

| 1988 | 196 | 28.6% | 0.74 (0.49–1.13) | 0.65 (0.41–1.05) |

| 1990 | 231 | 19.9% | 0.45 (0.29–0.69) | 0.46 (0.29–0.74) |

| 1991 | 222 | 17.1% | 0.39 (0.25–0.61) | 0.38 (0.23–0.62) |

| 1993 | 244 | 19.3% | 0.43 (0.28–0.66) | 0.37 (0.23–0.60) |

| 1995 | 259 | 14.7% | 0.31 (0.20–0.48) | 0.26 (0.16–0.42) |

| 1997 | 202 | 17.8% | 0.38 (0.24–0.60) | 0.32 (0.19–0.53) |

| 1999 | 216 | 16.7% | 0.34 (0.21–0.53) | 0.36 (0.22–0.60) |

| 2001 | 277 | 18.4% | 0.37 (0.24–0.56) | 0.35 (0.22–0.56) |

| 2003 | 257 | 11.7% | 0.20 (0.13–0.33) | 0.23 (0.13–0.38) |

| 2005 | 168 | 17.3% | 0.31 (0.19–0.51) | 0.28 (0.16–0.49) |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree