Chapter 65 Venous Disease

Anatomy

To determine whether pathophysiology is present, precise knowledge of venous anatomy is essential. After the location and type of venous incompetence have been determined, a therapeutic plan can be constructed. Venous drainage of the legs is the function of two parallel and connected systems, the deep and superficial systems. The nomenclature of the venous system of the lower limb was revised in 2002 and the most relevant changes are addressed here.1 The revised nomenclature is delineated in Tables 65-1 and 65-2.

| ANATOMIC TERMINOLOGY | PROPOSED TERMINOLOGY |

|---|---|

| Greater or long saphenous vein | Great saphenous vein Superficial inguinal veins |

| External pudendal vein | External pudendal vein |

| Superficial circumflex vein | Superficial circumflex iliac vein |

| Superficial epigastric vein | Superficial epigastric vein |

| Superficial dorsal vein of clitoris or penis | Superficial dorsal vein of clitoris or penis |

| Anterior labial veins | Anterior labial veins |

| Anterior scrotal veins | Anterior scrotal veins |

| Accessory saphenous vein | Anterior accessory great saphenous vein |

| Posterior accessory great saphenous vein | |

| Superficial accessory great saphenous vein | |

| Smaller or short saphenous vein | Small saphenous veinCranial extension of small saphenous vein |

| Superficial accessory small saphenous vein | |

| Anterior thigh circumflex vein | |

| Posterior thigh circumflex vein | |

| Intersaphenous veins | |

| Lateral venous system | |

| Dorsal venous network of the foot | Dorsal venous network of the foot |

| Dorsal venous arch of the foot | Dorsal venous arch of the foot |

| Dorsal metatarsal veins | Superficial metatarsal veins (dorsal and plantar) |

| Plantar venous network | Plantar venous subcutaneous network |

| Plantar venous arch | |

| Plantar metatarsal veins | Superficial digital veins (dorsal and plantar) |

| Lateral marginal vein | Lateral marginal vein |

| Medial marginal vein | Medial marginal vein |

| ANATOMIC TERMINOLOGY | PROPOSED TERMINOLOGY |

|---|---|

| Femoral vein | Common femoral vein |

| Femoral vein | |

| Profunda femoris vein or deep vein of thigh | Profunda femoris vein or deep femoral vein |

| Medial circumflex femoral vein | Medial circumflex femoral vein |

| Lateral circumflex femoral vein | Lateral circumflex femoral vein |

| Perforating veins | Deep femoral communicating veins (accompanying veins of perforating arteries) |

| Sciatic vein | |

| Popliteal vein | Popliteal vein |

| Sural veins | |

| Soleal veins | |

| Gastrocnemius veins | |

| Medial gastrocnemius veins | |

| Lateral gastrocnemius veins | |

| Intergemellar vein | |

| Genicular veins | Genicular venous plexus |

| Anterior tibial veins | Anterior tibial veins |

| Posterior tibial veins | Posterior tibial veins |

| Fibular or peroneal veins | Fibular or peroneal veins |

| Medial plantar veins | |

| Lateral plantar veins | |

| Deep plantar venous arch | |

| Deep metatarsal veins (plantar and dorsal) | |

| Deep digital veins (plantar and dorsal) | |

| Pedal vein |

Superficial Venous System

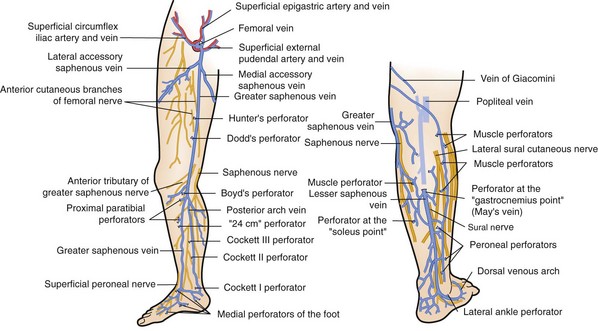

The superficial veins of the lower extremity form a network that connects the superficial dorsal veins of the foot and deep plantar veins. The dorsal venous arch, into which empty the dorsal metatarsal veins, is continuous with the great saphenous vein medially and the small saphenous vein laterally (Fig. 65-1).

The great saphenous vein, in close proximity to the saphenous nerve, ascends anterior to the medial malleolus, crosses and then medial to the knee (Fig. 65-2). It ascends in the superficial compartment and empties into the common femoral vein after entering the fossa ovalis. Before its entry into the common femoral vein, it receives medial and lateral accessory saphenous veins, as well as small tributaries from the inguinal region, pudendal region, and anterior abdominal wall. The posterior arch vein drains the area around the medial malleolus and, as it ascends up the posterior medial aspect of the calf, it receives medial perforating veins, termed Cockett’s perforators, before joining the great saphenous vein at or below the knee.

Perforating Venous System

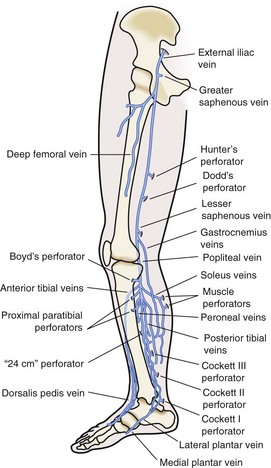

Perforating veins connect the superficial venous system to the deep venous system by penetrating the fascial layers of the lower extremity. These perforators run in a perpendicular fashion to the axial veins previously described. Although the total number of perforator veins is variable, up to 100 have been documented. The perforators enter at various points in the leg—the foot, medial and lateral calf, and mid and distal thigh (Fig. 65-3) Some have been named Cockett’s perforators, which connect the posterior arch and posterior tibial veins, Boyd’s perforators, which connect the great saphenous and gastrocnemius veins, and Hunterian and Dodd’s perforators, which connect the great saphenous and superficial femoral veins. The perforator veins have an important function. Their valve system aids in preventing reflux from the deep to the superficial system, particularly during periods of standing and ambulation.

Venous Insufficiency

Primary Venous Insufficiency

Pathology

Mechanical Abnormalities

Anatomic differences in the location of the superficial veins of the lower extremities may contribute to the pathogenesis. Primary venous insufficiency may involve both the axial veins (great and small saphenouss), either, or neither. Perforating veins may be the sole source of venous pathophysiology, perhaps because the great saphenous vein is supported by a well-developed medial fibromuscular layer and fibrous connective tissue that bind it to the deep fascia. In contrast, tributaries to the small saphenous vein are less supported in the subcutaneous fat and are superficial to the membranous layer of superficial fascia (Fig. 65-4). These tributaries also contain less muscle mass in their walls. Thus, these veins, and not the main trunk, may become selectively varicose.

Cellular Abnormalities

Changes also occur at the cellular level. Angioscopic observation demonstrates monocytic and macrophage infiltration in those vein valves affected by venous insufficiency. In regions of chronic advanced venous insufficiency, such as advanced lipodermatosclerosis, capillary proliferation is seen and extensive capillary permeability occurs as a result of the widening of interendothelial cell pores. Transcapillary leakage of osmotically active particles occurs, mainly of fibrinogen. In chronic venous insufficiency (CVI), venous fibrinolytic capacity is diminished and the extravascular fibrin remains to prevent the normal exchange of oxygen and nutrients in the surrounding cells.2 However, little proof exists for an actual abnormality in the delivery of oxygen to the tissues.

Molecular Abnormalities

On a molecular level, several abnormalities have been identified in extremities that manifest venous hypertension. Fundamental defects in the strength and characteristics of the venous wall have been identified. Varicose veins demonstrate decreased amounts of elastin and collagen, suggesting a contributing role toward venous pathophysiology.3

Risk Factors

Risk factors for the development of varicose veins include advancing age, female gender, heredity, and history of trauma to the extremity. Venous function is undoubtedly influenced by hormonal changes. In particular, progesterone liberated by the corpus luteum stabilizes the uterus by causing the relaxation of smooth muscle fibers.2 This directly influences venous function. The result is passive venous dilation, which in many cases causes valvular dysfunction. Although progesterone is implicated in the first appearance of varicosities in pregnancy, estrogen also has profound effects. It produces the relaxation of smooth muscle and a softening of collagen fibers. Furthermore, the estrogen-to-progesterone ratio influences venous distensibility. This ratio may explain the predominance of venous insufficiency symptoms on the first day of a menstrual period, when a profound shift occurs from the progesterone phase of the menstrual cycle to the estrogen phase. Although heredity is widely acknowledged as a risk factor for varicose vein development, the precise genetic mechanism has yet to be elucidated.

Physical Examination

The venous examination includes assessment of the patient in the standing and supine positions. Standing increases venous hypertension and dilates veins, thereby facilitating examination. Patients with superficial axial incompetence commonly exhibit palpable great saphenous veins (Fig. 65-5). Palpable cords may be present. Visual inspection is critical. Signs of advanced venous insufficiency include hyperpigmentation in the gaiter distribution, secondary to hemosiderin deposition, and lipodermatosclerosis. Lipodermatosclerosis develops over time, due to prolonged ambulatory venous hypertension and chronic inflammation. Physical examination findings that reflect lipodermatosclerosis are: brawny edema of the distal calf, “champagne bottle leg,” fibrotic, hypertrophic skin, and hyperpigmentation. Advanced lipodermatosclerosis may involve fibrosis of the Achilles tendon, impairing motor function of the extremity. Atrophie blanche is an area of pale hue, visualized around the medial malleolus; it is commonly mistaken for a healed ulcer because of its lighter pigmentation (Fig. 65-6). Corona phlebectica is a term used to describe an accumulation of tiny telangiectasias or venous flare, usually located at the medial malleolus.

Diagnostic Evaluation of Venous Dysfunction

Another instrument reintroduced to assess physiologic function of the muscle pump and venous valves is air displacement plethysmography.4 Its use was discontinued after the 1960s because of its cumbersome nature. Computer technology has now allowed its reintroduction, as championed by Christopoulos and colleagues.5 It consists of an air chamber that surrounds the leg from knee to ankle. During calibration, leg veins are emptied by leg elevation and the patient is then asked to stand so that leg venous volume can be quantitated and the time for filling recorded. The filling rate is then expressed in milliliters per second, thus giving readings similar to those obtained with the mercury strain gauge technique.

Duplex technology more precisely defines which veins are refluxing by imaging the superficial and deep veins. The duplex examination is commonly done with the patient supine, but this yields an erroneous evaluation of reflux. In the supine position, even when no flow is present, the valves remain open. Valve closure requires a reversal of flow with a pressure gradient that is higher proximally than distally. Thus, the duplex examination needs to be done with the patient standing or in the markedly trunk-elevated position.6,7

Imaging is obtained with a 7.5- or 10-MHz probe; the pulsed Doppler consists of a 3.0-MHz probe. The patient stands, with the probe placed longitudinally on the groin. After imaging, sample volumes can be obtained from the femoral and saphenous veins. This flow can be observed during quiet respiration or distal augmentation. Sudden release of augmentation allows the assessment of valvular competence. The small saphenous vein and popliteal veins are similarly examined. Reflux times of 3 seconds or longer is considered significant. Perforator veins can be visualized well with the duplex examination. Demonstration of duplex images of to and fro flow, with the presence of dilated segments, constitutes findings compatible with a refluxing perforator. Additionally, Doppler studies can provide the clinician with information about the deep system. Widespread use of duplex scanning has allowed a comparison of findings between standard clinical examinations and duplex Doppler studies.8

Classification Systems

In 1994, the American Venous Forum devised the CEAP classification system, which is a scoring system that stratifies venous disease based on clinical presentation, etiology, anatomy, and pathophysiology (Table 65-3). It is useful in helping the physician assess a limb afflicted with venous insufficiency and then arrive at an appropriate treatment plan. A revised CEAP was introduced that included a venous disability score (VDS) to document a patient’s ability to perform activities of daily living.9 Although the CEAP classification is a valuable tool to grade venous disease, assessment of outcomes following intervention cannot be realized. As a result, two additional scoring systems, the venous clinical severity scoring system (VCSS) and venous segmental disease score (VSDS), enhance the CEAP score with the increased ability to plot outcome. These three classification modalities now provide clinical researchers with invaluable tools to study treatment outcomes.10

Table 65-3 Classification of Chronic Lower Extremity Venous Disease

| C | Clinical signs (grade0-6), supplemented by “A” for asymptomatic and “S” for symptomatic presentation |

| E | Classification by cause (etiology)—congenital, primary, secondary |

| A | Anatomic distribution—superficial, deep, or perforator, alone or in combination |

| P | Pathophysiologic dysfunction—reflux or obstruction, alone or in combination |

| Clinical Classification (C0-6) | |

| Any limb with possible chronic venous disease is first placed into one of seven clinical classes (C0-6), according to the objective signs of disease. | |

| Clinical Classification of Chronic Lower Extremity Venous Disease* | |

| CLASS | FEATURES |

| 0 | No visible or palpable signs of venous disease |

| 1 | Telangiectasia, reticular veins, malleolar flare |

| 2 | Varicose veins |

| 3 | Edema without skin changes |

| 4 | Skin changes ascribed to venous disease (e.g., pigmentation, venous eczema, lipodermatosclerosis) |

| 5 | Skin changes as defined above with healed ulceration |

| 6 | Skin changes as defined above with active ulceration |

| *Limbs in higher categories have more severe signs of chronic venous disease and may have some or all of the findings defining a less severe clinical category. Each limb is further characterized as asymptomatic (A)—for example, C0-6,A—or symptomatic (S)—for example, C0-6,S. Symptoms that may be associated with telangiectatic, reticular, or varicose veins include lower extremity aching, pain, and skin irritation. Therapy may alter the clinical category of chronic venous disease. Limbs should therefore be reclassified after any form of medical or surgical treatment. | |

| Classification by Cause (EC, EP, or ES) | |

| Venous dysfunction may be congenital, primary, or secondary. These categories are mutually exclusive. Congenital venous disorders are present at birth but may not be recognized until later. The method of diagnosis of congenital abnormalities must be described. Primary venous dysfunction is defined as venous dysfunction of unknown cause but not of congenital origin. Secondary venous dysfunction denotes an acquired condition resulting in chronic venous disease—for example, deep venous thrombosis. | |

| Classification by Cause of Chronic Lower Extremity Venous Disease | |

| Congenital (EC) | Cause of the chronic venous disease present since birth |

| Primary (EP) | Chronic venous disease of undetermined cause |

| Secondary (ES) | Chronic venous disease with an associated known cause (e.g., post-thrombotic, post-traumatic, other) |

| Anatomic Classification (AS, AD, or AP) | |

| The anatomic site(s) of the venous disease should be described as superficial (AS), deep (AD), or perforating (AP) vein(s). One, two, or three systems may be involved in any combination. For reports requiring greater detail, the involvement of the superficial, deep, and perforating veins may be localized by use of the anatomic segments. | |

| Segmental Localization of Chronic Lower Extremity Venous Disease | |

| SEGMENT NO. | VEIN(s) |

| Superficial Veins (AS1-5) | |

| 1 | Telangiectasia/reticular veins |

| Greater (long) saphenous vein | |

| 2 | Above knee |

| 3 | Below knee |

| 4 | Lesser (short) saphenous vein |

| 5 | Nonsaphenous |

| Deep Veins (AD6-16) | |

| 6 | Inferior vena cava |

| ILIAC | |

| 7 | Common |

| 8 | Internal |

| 9 | External |

| 10 | Pelvic: gonadal, broad ligament |

| FEMORAL | |

| 11 | Common |

| 12 | Deep |

| 13 | Superficial |

| 14 | Popliteal |

| 15 | Tibial (anterior, posterior, or peroneal) |

| 16 | Muscular (gastrointestinal, soleal, other) |

| 17 | Thigh |

| 18 | Calf |

| Pathophysiologic Classification (PR,O) | |

| Clinical signs or symptoms of chronic venous disease result from reflux (PR), obstruction (PO), or both (PR,O). | |

| Pathophysiologic Classification of Chronic Lower Extremity Venous Disease | |

| Reflux (PR) | |

| Obstruction (PO) | |

| Reflux and obstruction (PR,O) | |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree