Intra-operative views of a left pleural cavity: the phrenic pedicle passes from the pericardium’s left side to the left hemidiaphragm’s upper part. In case of sudden deceleration, a rupture may occur at the neuromuscular junction.

Clinical presentation

A UDP may be unnoticed in 50% of patients with moderate to low activity and revealed on chest X-ray. Postural or effort dyspnoea is the most commonly observed symptom. Antepnoea, also called the ‘shoelace sign’, almost formally proves the diaphragmatic damage. In a lying position during sleep, the elevation of the hemidiaphragm is increased, giving hypoventilation and hypoxemia. A ventilatory support using non-invasive ventilation may be proposed to improve the apnoeic syndrome. Recurrent bronchopulmonary infections or cardiac dysrhythmias may occur, being directly linked to the local compression and mediastinal shift. The stomach horizontalization leads to digestive disorders including epigastric pain, strong and painful eructations and gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Co-morbidity factors such as obesity, cardiomyopathy or pre-existing underlying bronchopulmonary disease potentiate the functional consequences of eventration[3].

Morphological and functional assessments

Chest radiography (profile and front) associated with dynamic X-ray (inspiration and expiration) views are enough to diagnose the eventration and to appreciate its severity. The mediastinal shift shows a major amyotrophied form which is always very symptomatic. In major forms, a paradoxical cranial movement of the distended hemidiaphragm is observed during inspiration due to an increase of abdominal pressure.

Diaphragm ultrasonography is a simple test which allows analysis of diaphragm mobility, but its results may depend on the operator, decreasing its relevance for surgeons.

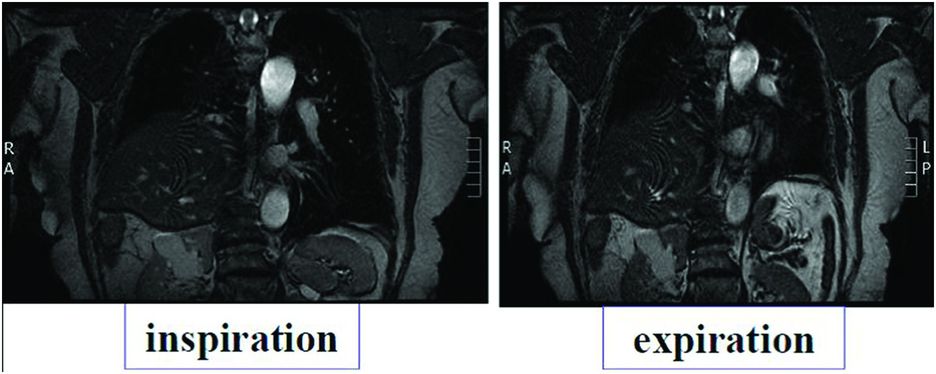

Cervicothoracic CT scan and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are useful and unavoidable tools in the diagnosis of aetiology and for evaluation of local consequences (Figure 22.2). Performed in the supine position, they increase the elevation of the hemidiaphragm and show what happens during sleep. They allow the detection of a tumour that can be located on the course of the phrenic nerve somewhere between its root and its end. Local compressions may also be evaluated.

Pulmonary function tests usually show a restrictive syndrome of which severity depends on the importance of the elevation and co-morbidity criteria. The vital capacity reduction, which often exceeds 50%, is further aggravated during transition from a sitting to a supine position. The effect is more evident in right-sided DP.

Full-night polysomnography is interesting to detect a possible sleep apnoea syndrome.

Electrophysiological study is essential to evaluate the conduction of the nerve and to measure the capacity of the muscle to get an efficient contraction[7,8]. It includes surface electromyography (EMG) of costal diaphragm, needle EMG of the diaphragm (usually contraindicated in chronic obstructive lung disease and ventilated patients because of the risk of pneumothorax), gastric and oesophageal catheters (to measure transdiaphragmatic pressure, commonly considered to be proportional to the force generated by the diaphragm) and cervical stimulation tests (magnetic and electric to measure the conduction time of each nerve). The tests can be repeated to follow the evolution over time and detect possible recovery.

Indication for surgery: When an eventration is diagnosed, it is important to avoid unnecessary surgery and to evaluate precisely its reversibility, which can occur months to years later[9]. This reversibility is evaluated according to a set of arguments, including

○ The initial mechanism of the trauma: a phrenic nerve section is obviously definitive but a cervical trauma may recover,

○ The time since the onset of the paralysis,

○ The importance of the hemidiaphragm distension, and

○ The results of the stimulation tests. One should keep in mind that a significant distension of the hemidiaphragm with a thinning of the muscular part is usually the sign of an irreversible amyotrophy even if the nervous conduction has already recovered.

Surgery can be proposed in case of a significant elevation of the hemidiaphragm (more than two or three intercostal spaces on chest X-ray) if the tests show a major dysfunction of the diaphragm, with important functional consequences for the patient and no hope of spontaneous recovery. Before surgery, co-morbidity factors must be controlled – tobacco weaning, active bronchial physiotherapy, weight reduction and sleep apnoeic syndrome.

Asymptomatic or minimally symptomatic eventrations do not require any prophylactic surgical treatment, even in complete hemidiaphragm paralysis confirmed by stimulation tests. A simple follow-up must be proposed to these patients.

Formal contraindications

Morbid obesity is a contraindication because of the high risk of post-operative morbidity and mortality, technical challenge and poor functional results. For these patients, a strict slimming diet is the first measure to propose, sometimes associated with non-invasive ventilation and/or even bariatric surgery. Diffuse neuromuscular disorders (i.e. amyotrophic lateral sclerosis) and pleural tumour represent a contraindication because of short-term pejorative vital prognosis and poor functional benefits. General co-morbidity factors (cardiac or renal failure) must also contraindicate this surgery, temporarily or definitively.

Objective and principles of the surgical treatment of unilateral eventration

Tightening the distended hemidiaphragm using plication[3,10] is the only accepted surgical treatment for a symptomatic eventration. Suggested by Wood in 1916, this technique was used successfully for the first time by Morrison in 1923[11]. Since then, hemidiaphragm plication has only been infrequently performed and reported in the medical literature[10,12–18]. The objective of this treatment is to improve symptoms by pulling down the hemidiaphragm and restoring its anatomical position. This procedure does not restore the active contraction of the muscle; however, it restores the position of both abdominal and thoracic organs, decreases compression and stops the paradoxical movements of the diaphragm, improving the function of the healthy contralateral hemidiaphragm.

When should plication be used?

There is no consensus regarding the time between diagnosis and plication. To plan surgery, the key elements are a good understanding of the mechanism of the lesion and the importance of symptoms. Surgery should be proposed without delay in case of irreversible respiratory decompensation requiring assisted ventilation.

Three different approaches have been described to perform plication. To date, the reference technique is a plication of the hemidiaphragm performed via a limited lateral thoracotomy approach[10,13,16–18]. More recently, plication via video-assisted thoracoscopic approach (VATS) has been proposed by Mouroux and colleagues[15] and later done by other expert centres[14]. In 2004, Huttl[19] first described the laparoscopic approach, and other rare successful cases were reported[20].

Open thoracic approach associated with thoracoscopy

Technical aspects

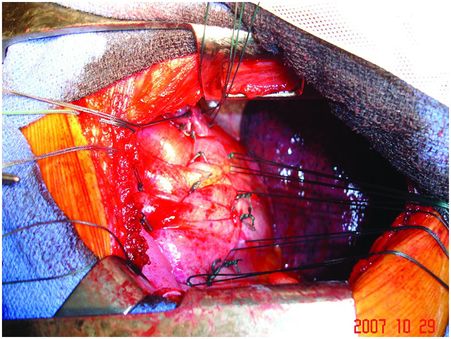

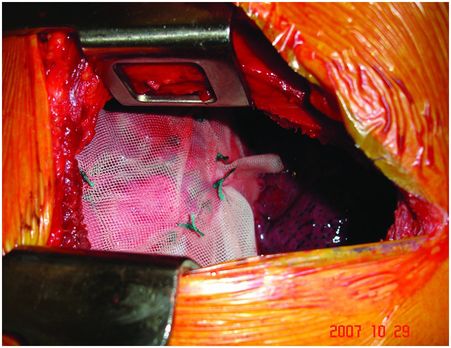

Under general anaesthesia with double-lumen intubation, the patient is placed in a lateral position. A nasogastric tube is positioned to completely empty the stomach. The thoracoscope is inserted to determine the exact level of thoracotomy. A small lateral thoracotomy is performed (usually through the seventh or eighth intercostal space), and a rib retractor is positioned. After removal of the pleural symphysis, if necessary, a complete local exploration is done. It concerns the thickness of the peripheral muscle, the general aspect of the hemidiaphragm and the whole phrenic nerve all along its course from the apex to its end on the muscle. The hemidiaphragm is then manually tensioned and folded to determine the exact level of the plication plane. This suture area must be chosen on the peripheral muscular parts, thus preserving the phrenic nerve and its branches. It is most often a transverse fold, lined up from the pericardial region (in front of or behind the phrenic pedicle) to the lateral chest wall. We suggest to perform a short opening of the central tendon in order to control the position of the abdominal organs and thus to avoid injuring them when passing the suture through (Figure 22.3). The re-tensioning of the hemidiaphragm allows one to determine the exact position of the U stitches placed on both sides of the fold. The eventrated diaphragm is grasped with Babcock clamps, and the excess portion is sutured at the base with non-absorbable mattress sutures (with or without pledgets). These stitches are not tied but put on hold on a clamp. Then, when all stitches are positioned, they are tied up while checking the quality of the whole re-tensioning and shape of the hemidiaphragm. If necessary, some stitches may be added to avoid any organ strangulation inside the suture. The opening performed inside the central tendon at the beginning of the procedure is then closed by a non-absorbable continuous suture (Mersuture; Johnson & Johnson, New Brunswick, NJ) with threads. The fold is then sutured laterally to reinforce the first plication (Figure 22.4). In case of major amyotrophia, we systematically reinforce the diaphragm using a prosthetic mesh in non-absorbable mattress, using additional stiches positioned on the peripheral muscle at the beginning of the surgical procedure (Figure 22.5). To reinforce the plication, several rows of double-armed non-absorbable sutures parallel to the sagittal plane may be used without any opening of the central tendon.

The short opening of the central tendon allows control of the position of the abdominal organs, avoiding injury, when passing the sutures.

The prosthetic mesh in non-absorbable mattress is sutured laterally to reinforce the muscular plication.

Results

Observational retrospective studies and few studies of unpaired control cases[12,13] have been reported. Respiratory functional improvement is almost always observed earlier and sustained in the long term[10,12–14,16,17]. The subjective benefit is measured using different criteria according to the series. It may be a simple questioning, a measure of dyspnoea score using an analog scale or a more complex scale such as the Medical Research Council (MRC) dyspnoea score. The objective results are measured on post-operative flow and volume improvements. The mean improvements of the vital capacity (VC) and the forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) are in the range of 10 to 20%[13,16,17,21], also assessed in the supine position[21]. In Versteegh’s series, all the patients could sleep again in the supine position, and non-invasive ventilation was stopped in the three patients who had it before operation[21]. This benefit persists on long-term follow-up despite a downward trend, as reported in Higgs’s series, where 15 of the 19 operated patients had a mean follow-up of 10 years[16]. The blood exchanges also improve, with a significant arterial pressure in oxygen ranging from 7 to 13 mmHg[10,17]. The advantages of thoracotomy are to allow an excellent approach of the whole diaphragm and to apply re-tensioning of the hemidiaphragm with maximal security for all intra-peritoneal organs.

Thoracoscopic plication

History

The first successful VATS approach to treat diaphragm eventration in adults was described in 1996 by Mouroux and colleagues[22]. Then it was developed in paediatry, even in newborns, to avoid the constant disadvantages of thoracotomy. In adults, few centres performed the diaphragm plication using this approach[14,15].

Technical aspects

Under general anaesthesia with double-lumen intubation, a nasogastric tube is inserted to completely empty the stomach. The patient is positioned in the full lateral position. Two 5-mm ports are inserted in the fifth intercostal space on the posterior axillary line (for 5-mm 30-degree angled scope) and on the mammary line (for the grasper), respectively. A short thoracotomy 5-cm working incision is performed in the nineth intercostal space on the posterior axillary line. No rib retraction is generally required, and conventional surgical instruments are introduced through the thoracotomy. An endoscopic clamp introduced through the anterior port is used to grasp and invaginate the apex of the eventration downward into the abdomen. A transverse fold is thus created from the periphery to the cardiophrenic angle behind the phrenic nerve. This fold is first closed using a non-absorbable running suture beginning at the periphery of the diaphragm. The first row is superficial to avoid injury to the abdominal organs. Once at the cardiophrenic angle, the suture is drawn tight, while the clamp used to push the diaphragm downward is removed. A row of return stitches is created along the same axis, and the suture is tied with the free end of the first knot. During the placement of these return stitches, the assistant keeps the suture material taut using forceps introduced through the posterior port. The tension applied in this manner facilitates grasping of the edges of the fold to be sutured. This first back-and-forth series of running suture allows maintenance of the excess of diaphragm within the abdomen, and care is taken to avoid applying tension to this first series of suture. A second back-and-forth series of running suture is carried out similarly, thus burying the first series of suture lines: stitches are inserted through a more peripheral portion of the diaphragm to obtain the desired tension of the hemidiaphragm. Chest drainage is achieved using a single chest tube introduced through the anterior port.

Results

Significant improvements in the functional status were reported in short series[14,15]. At 6-month follow-up in the VATS group, mean forced VC, FEV1, functional residual capacity (FRC) and total lung capacity (TLC) improved by 17, 21, 20 and 16%, respectively (p < 0.005). Mean MRC dyspnoea scores also improved significantly in the operated cohort (p < 0.001). In the short Kim’s series including four patients treated by exclusive tidal volume (VT) plication (without minithoracotomy), no eventration recurrence was observed at 6-month follow-up[23]. However, at 12-month follow-up, a slight elevation of the hemidiaphragm was observed in one patient, but no new surgical procedure was necessary. A validation of these results obtained by minimally invasive technique is needed based on larger prospective studies. Such studies are probably difficult to conduct because of scarcity of the disease and the lack of thoracic surgeons experienced in this disease.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree