CXR of a patient 2 weeks after pneumonectomy ventilated via a tracheostomy.

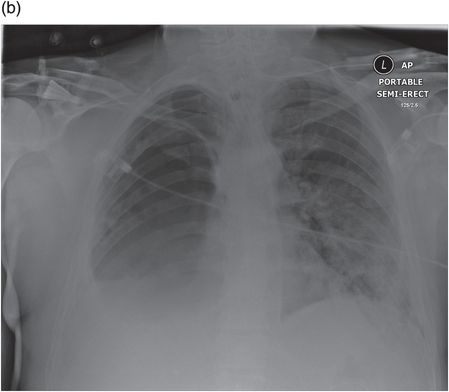

The same patient 12 hours later after developing a BPF; the fluid level in the pneumonectomy space has dropped dramatically.

Surgical techniques to avoid BPF

As mentioned earlier, risk factors for BPF include leaving a long bronchial stump and devascularization of the bronchial stump by excessive diathermy or skeletonization. These factors are avoided relatively easily. When comparing handsewn or stapled bronchial stumps, there is no clear advantage to either technique with experienced operators[6]. Though, as a stapled technique is very reproducible and simple to teach, it is now the most commonly used method in UK centres. Further measures to avoid fistula formation include covering the bronchial stump at the time of resection. Most authors agree that a vascularized tissue should be used to promote early healing of the bronchial stump, and a wide variety of tissues have been used for this purpose, including pleura, intercostal muscle, diaphragm, pericardium, azygous vein and omentum[5,10,11]. Asamura and Naruke as well as Klepetko have all suggested that a pedicled pericardial flap covering the bronchial stump is a good method to decrease incidence of BPF in their reported series[3,14]. There is reasonable agreement that following a right pneumonectomy the bronchial stump should be covered due to the increased risk of BPF on this side. With a left pneumonectomy, however, some surgeons do not routinely cover the stump as the stump tends to retract behind the aorta and is surrounded by well-vascularized mediastinal tissues which can be closed over the stump.

Treatment strategies for BPF

As mentioned earlier, in early BPFs, aspiration of pleural fluid into the contralateral lung is a common problem which leads to a high mortality rate. This means that in such patients thorough early drainage of the pleural space on the side of the BPF must be achieved to avoid contamination of the contralateral lung. Drainage is commonly closed via intercostal drains. Antibiotics to treat any pleural space infection are also normally given as the pleural space associated with a BPF must be presumed to be infected unless proven otherwise. Bronchoscopy is performed both to attempt to identify the fistula and to clear any secretions or suction-contaminated pleural fluid from the contralateral lung and airways. In patients requiring ventilation, this may be necessary via a double-lumen tube or a long ET tube selectively intubating the contralateral bronchus to protect the unaffected side from aspiration of pleural fluid. The immediate management of an early BPF can be summarized as protection of the airway (by drainage, clearance of fluid secretions and possible selective ventilation) and treatment of infection by appropriate antibiotic cover.

Large fistulae that present early after lung resection are often best managed by exploration and operative repair as long as the patient is stable enough to tolerate the procedure and there is not heavy contamination of the pleural cavity[12,13]. When repaired early like this, techniques such as stump resection or revision can be used, and in the case of post-lobectomy BPF, completion pneumonectomy may be an option. Khan et al. suggested that direct closure is possible in around 80% of patients, and it is suggested that the stump be covered in a vascularized pedicle flap, as mentioned earlier[16]. Thorough washout of the space together with antibiotics delivered by continous irrigation and systemically have rarely prevented the development of post-pneumonectomy empyema.

Where there is an established empyema associated with a bronchopleural fistula, this is more difficult to treat, and treatment has two main goals: to close the fistula and to sterilize or obliterate the pleural space. It is commonly suggested that definitive surgical repair is not carried out until the pleural space infection is cleared and the patient is in the best possible condition for surgery[15]. Various methods have been used to attempt to clear infection from the pleural space, including irrigation with saline, dilute iodine solution or antibiotic installations along with continued administration of IV antibiotics[15,16]. Even with these strategies, it is often not possible to clear the pleural space infection with closed drainage, and open thoracostomy drainage can be necessary. A commonly used technique to deal with BPFs associated with empyema is the Clagett procedure; this is a two-stage procedure consisting of open pleural drainage, closure of the BPF, removal of the necrotic tissue and then secondary closure or obliteration of the pleural cavity with antibiotic solution[14,15]. This procedure was developed at the Mayo Clinic and modified there by Pairolero et al. to include intrathoracic muscle flap transposition to reinforce the closed BPF[16]. With this technique, they reported 84% of patients in whom the procedure was completed having a healed chest wall with no evidence of recurrent infection and the BPF remaining closed in 86%[19]. Though these techniques report good outcomes, they can involve multiple surgical procedures, prolonged hospital stays and extended periods of open chest drainage and packing[17]. Gharagozloo et al. have suggested that pleural space irrigation can speed up this process; however, they also suggest that this is only appropriate for early-stage BPFs, not those with established indurated pleural tissue[18].

Where there is still a large pleural space present, other techniques can be used to obliterate this space. Historically, thoracoplasty was commonly used for this purpose, but increasingly now, the space is filled with muscle flaps or omentum. Muscles flaps which can be used to fill the pleural space include latissimus dorsi, pectoralis major, serratus anterior, pectoralis minor, rectus abdominis and intercostal muscle[19–21]. Omentum is especially good for filling irregularly shaped cavities and is normally very vascular promoting rapid healing[15]. In malnourished patients, however, it can have little bulk and become less useful. Sometimes for very large spaces a combination of limited thoracoplasty and muscle transposition may be useful.

There have also been a variety of bronchoscopic techniques which have been employed to attempt to deal with BPFs. These have generally been carried out in patients either deemed to unwell to undergo surgical correction under general anaesthetic or in patients with small BPFs who are quite well and wish to avoid invasive surgery. Many materials and devices have been used to try to close fistulae including ethanol silver nitrate, cyanoacrylate compounds, coils, lead plugs, balloons, fibrin or tissue glue, antibiotics, gel foam, spigots, autologous blood patches and more recently Amplatzer-type devices[22–24]. All of these techniques have had variable success rates and in general seem to work best on smaller and more peripheral fistula. It has been suggested they work best with fistulae around 1 mm and have no real use in fistulae above 8 mm[25]. As mentioned earlier, they are often used in patients where major surgery is not an option. In summary, the principles of treatment of a BPF are protection of the airway and treatment of infection initially, then closure of the fistula and management of the pleural space. Though endobronchial techniques have been used successfully, the most commonly employed methods of treatment with the highest success rates all involve major surgical intervention.

More recently, treatment strategies using some of the elements described earlier plus negative pressure wound therapy have been reported. Schneiter et al. have reported an accelerated treatment for post pneumonectomy empyema comprising multiple debridements and packing the chest with iodine soaked swabs with negative-pressure therapy and antibiotics[25]. In this report, they describe successfully treating 97% of 75 patients with a post-pneumonectomy BPF. Similar treatment has also been described by Perentes et al. with repeated intrathoracic VAC dressings until granulation tissue covered the entire chest cavity[26]. The current evidence regarding negative-therapy dressing for treatment of post–lung resection BPF and empyema was reviewed by Haghshenasskashani et al.[27]. The conclusions of this review were that negative-pressure therapies can potentially alleviate the morbidity and decrease hospital stay in patients with empyema after lung resection. As evidence grows regarding their use, they may play an important role in the treatment of BPF.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree