Type

Cause

Respiratory drive

Pharmacological

Drug overdose, anesthesia

Congenital

Central hypoventilation syndrome

Acquired

Cerebrovascular accident

Neuromuscular

Cervical spinal cord injury

Trauma

Chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy

Guillain–Barré syndrome

Anterior horn disease

Poliomyelitis

Phrenic nerve injury

Trauma, cardiac surgery

Muscles of respiration

Pharmacological

Neuromuscular blocks

Congenital

Hypophosphatemia

Acquired

Kyphoscoliosis, trauma

Rib cage

Decreased mobility

Alt. Pleura

Extrapulmonary restriction

Pneumothorax, pleural effusion

Airway

Upper airway obstruction

Epiglottitis, foreign body

Lower airway obstruction

Asthma

Increase in dead space

Increased ventilation/perfusion ratio

Emphysema

Decreased ventilation/perfusion ratio

Acute respiratory distress syndrome

General pulmonary hypoperfusion

Hypovolemia, cardiogenic shock

Localized hypoperfusion

Thromboembolism

Physiopathology

There are five physiopathological mechanisms that can alter the homeostasis of gases and lead to respiratory insufficiency: (1) an alteration in the alveolar ventilation and pulmonary perfusion ratio (V/Q ratio); (2) a shunt (short circuit); (3) hypoventilation; (4) an alteration in the diffusion of gases in the alveolocapillary membrane; and (5) a decrease in the concentration of inhaled oxygen. The three most important are the V/Q ratio, hypoventilation, and a shunt, with a decrease in inhaled O2 being considered a minor clinical implication of acute respiratory insufficiency.

Ventilation/Perfusion Alterations

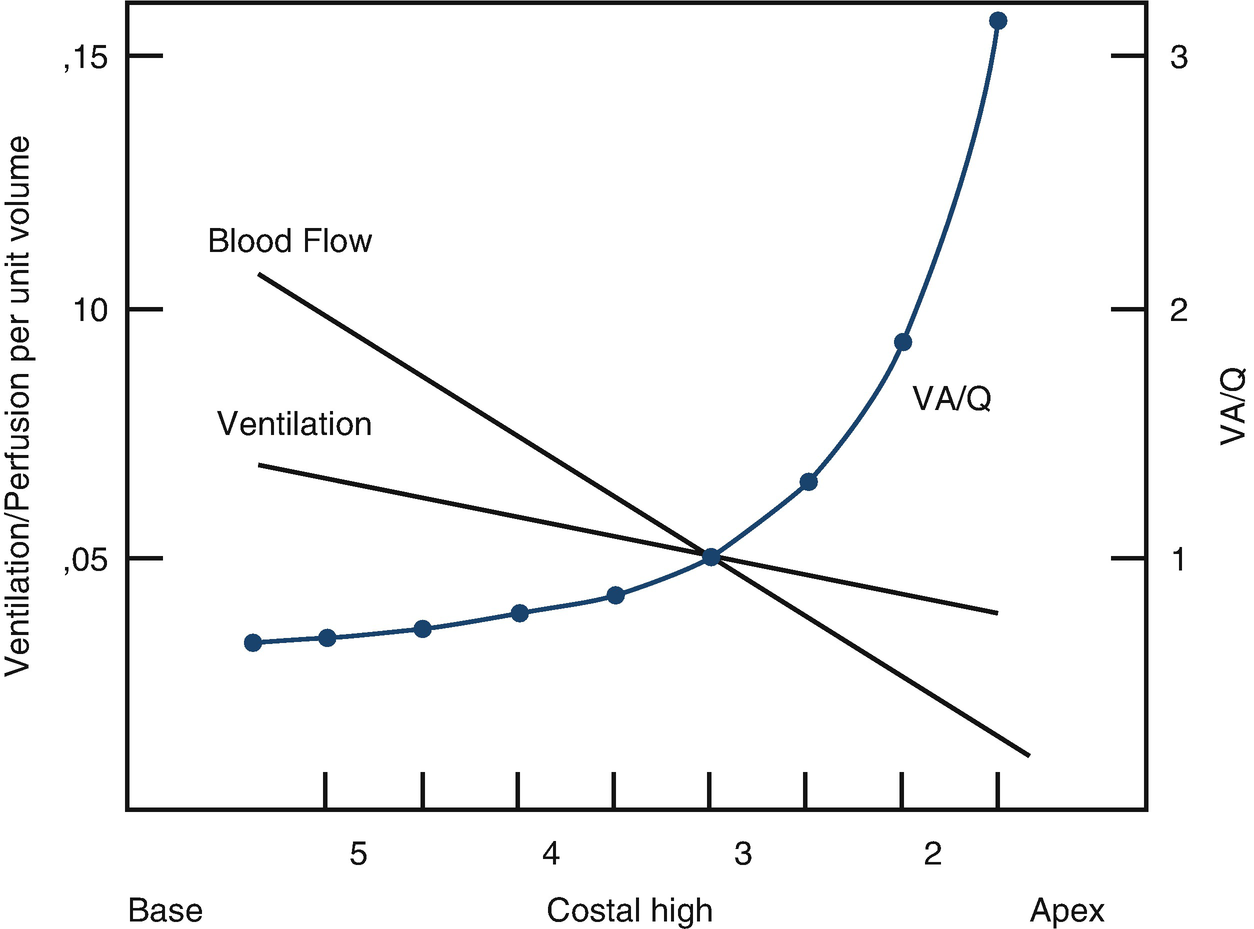

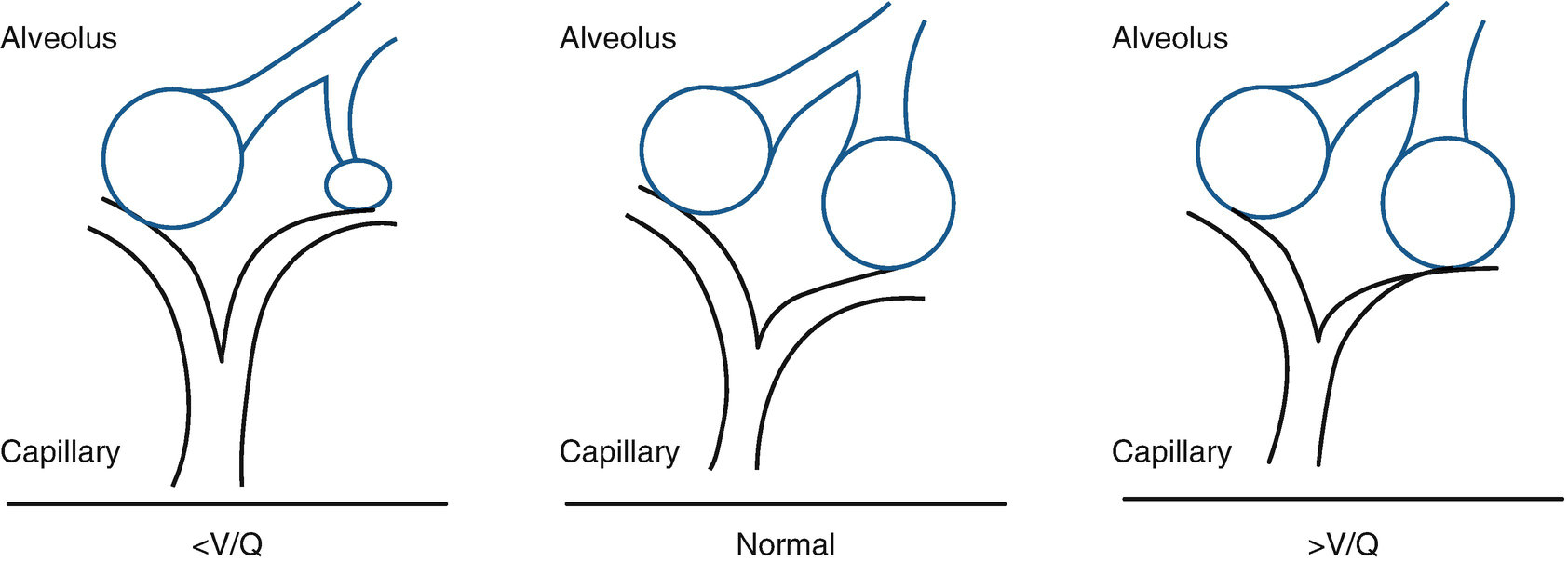

Ventilation distribution, blood flow, and ventilation/perfusion (V/Q) ratio

Ventilation/perfusion alteration

In a person who is breathing spontaneously, there are compensatory mechanisms to correct hypoxia and/or hypercarbia. In the context of hypoxemia, pulmonary vascular vasoconstriction consists of the alveolar units with better V/Q ratios an excluding those that are poorly ventilated, while the increase in VA as a response to hypoxia prevents an increase in PcO2, including lowering it to below normal levels.

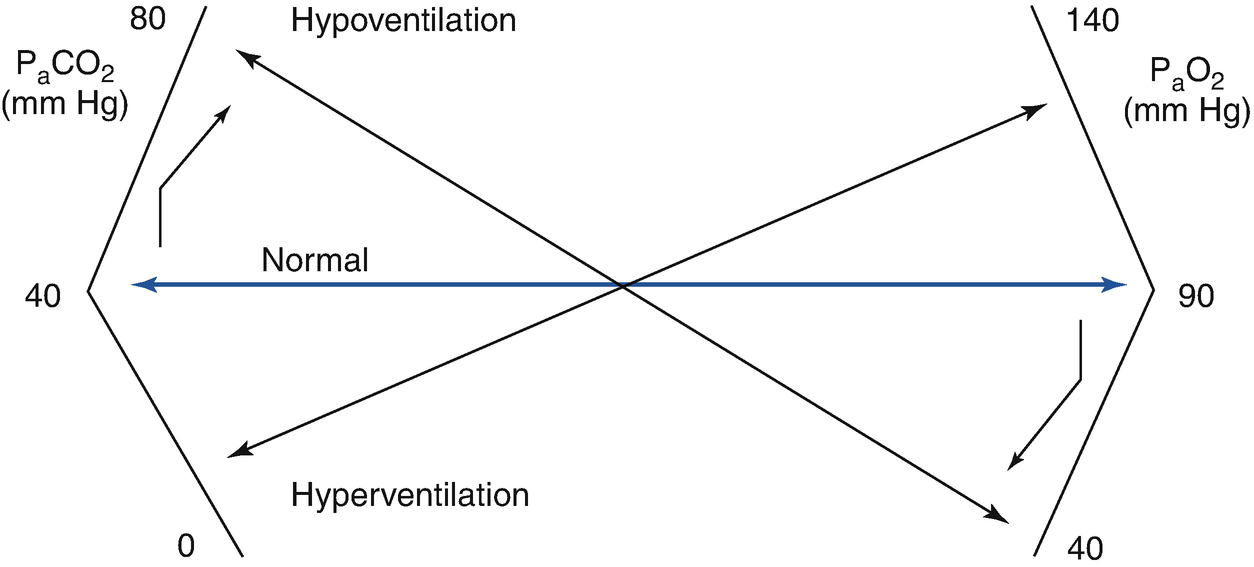

Hypoventilation

PaO2 is determined by the balance between oxygen provided by VA (which provides oxygen from inhaled air) and the extraction of oxygen by capillary blood. Consequently, when VA decreases significantly, PaO2 decreases and PcO2 increases, which are the fundamental characteristics of hypoventilation.

PcO2 is determined by VA and the production of CO2 (VCO2), multiplied by the K constant, as is seen in the formula PaCO2 = (VCO2/VA) × K, from which it can be deduced that increased CO2 production or a decrease in VA increases PaCO2. As the compensatory renal response to hypercarbia is slow (bicarbonate retention), there is an acute fall in arterial pH.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree