Cause

Laryngomalacia

Vocal cord paralysis

Congenital or acquired congenital stenosis

Laryngeal cleft

Laryngeal membrane

Subglottic hemangioma

Laryngeal papillomatosis

Cysts and laryngoceles

Laryngeal condylomatosis

Proximal tracheomalacia

Foreign body

Applied Physiopathology

Stridor is related to the anatomy of the central airway and airflow dynamics. There is a natural anatomical division of the airway at the level of the glottis or vocal cords. However, from the physiological point of view, the central airway is composed of an extrathoracic part (the nose, nasopharynx, larynx, and upper part of the trachea) and an intrathoracic part (the rest of the trachea and the bronchi). The thorax meets the neck at the level of the first dorsal vertebra, the first ribs, and the sternal manubrium.

The upper airway in children, and especially in infants, is funnel shaped and has a smaller diameter than that in adults; the tongue is proportionally larger, the location of the larynx is closer to the brain and to the anterior section, the tissues are more lax, and there is greater cartilaginous flexibility of the support structures. The cricoid cartilage is the narrowest airway segment in infants and preschool children, while the narrowest segment in newborns is the nose. In schoolchildren, the narrowest airway segment is the vocal cords.

According to this formula, a 50% decrease in the radius increases airflow resistance by 16 times and consequently produces a notable decrease in airflow. When the lumen of the airway is reduced, the velocity of the flow increases and induces the Bernoulli effect, which establishes that when the air velocity increases, the pressure exerted by the airflow in the lumen decreases and, in this case, facilitates the collapse of the airway. Finally, stridor is produced by distortions of the laminar flow and turbulence, with a vibratory effect on the adjacent tissue.

The diaphragm descends during inspiration; the ribs ascend and are in a horizontal position, generating negative pressure within the chest cavity and the airway. The structures that surround the extrathoracic airway are at atmospheric pressure, and so a pressure gradient is created that compresses this segment of the airway during inspiration. Stridor is produced when the airway is collapsible or is partially obstructed (for example, in patients with laryngomalacia or laryngitis, respectively).

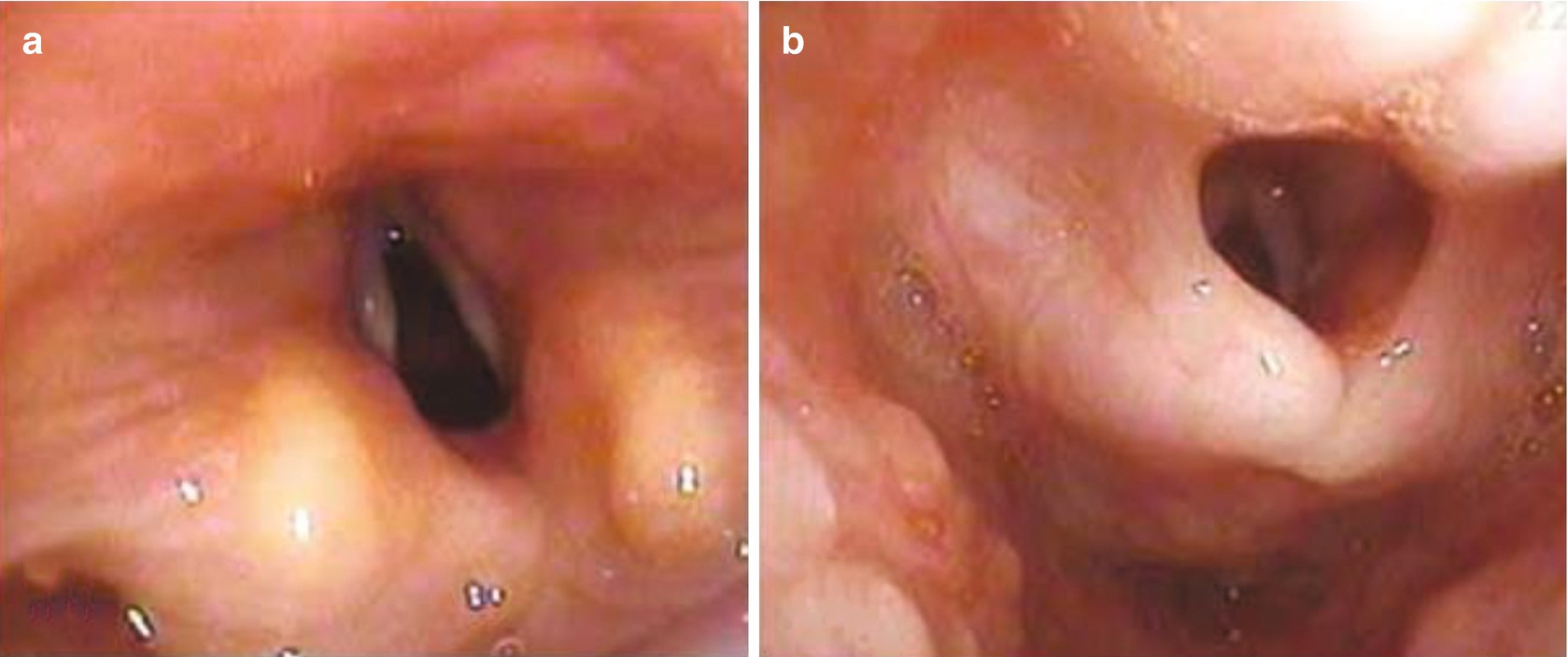

Laryngomalacia. On expiration (a), redundant mucosa is visible. On inspiration (b), the arytenoids partially obstruct the lumen and the epiglottis collapses in a cross direction

Viral laryngotracheobronchitis. The larynx shows erythema and edema in the entire glottis, including the cord and arytenoids

Clinical History

The clinical history is very helpful for diagnosing stridor, assessing its severity, and deciding on the therapeutic approach, including referral to a specialist.

Age at initiation: Congenital causes are most common in newborns, and the most common of these is laryngomalacia. The most common cause among preschool children is LTB, although the possibility of foreign body aspiration should always be considered. Croup usually presents in patients between 6 months and 6 years of age. An infant under 6 months of age with repeated LTB could have a subglottic anatomical anomaly.

Form of initiation: If stridor is acute and is associated with a fever, the etiology probably involves viral or bacterial infection. Abrupt initiation with respiratory difficulty or asphyxia suggests aspiration of a foreign body or an inflammatory cause (an allergic reaction).

Evolution timeline: A patient with stridor for more than a week after viral laryngitis could be suffering a complication such as bacterial tracheitis.

Chronology : Stridor caused by laryngomalacia becomes notable at 1–2 weeks after birth and can increase until 3 months of age, after which it decreases progressively, generally disappearing by 1 year of age. A subglottic hemangioma often appears at 2 months of age and is progressive, following the same course as hemangiomas of the skin.

Conditions that modify stridor: In children with laryngomalacia, stridor increases when they eat, cry, or lie on their back; it decreases when they lie face down or are asleep.

History of cervical or thoracic trauma or surgery: Lesions of the vagus nerve or its upper laryngeal or recurrent laryngeal branches can decrease the mobility of the vocal cords, including paralysis.

Association with apnea and cyanosis : This can occur in cases of laryngomalacia, but it can also appear in the presence of vascular rings and external causes not related to the airway.

History of intubation: This indicates the presence of acquired subglottic stenosis.

Association with feeding difficulty: This can indicate the presence of acid reflux or an anatomical anomaly, such as a laryngeal cleft or a tracheoesophageal fistula. It also constitutes a symptom of the seriousness of the airway obstruction.

Physical growth: Alterations can be due to greater respiratory work that indicates the seriousness of the obstruction.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree