Anatomy of cough

Etiology

- 1.

The causes of chronic cough in children and adults are different, and within pediatrics they can differ among infants, preschool children, and schoolchildren and adolescents.

- 2.

The etiological spectrum can include one or more coexisting causes.

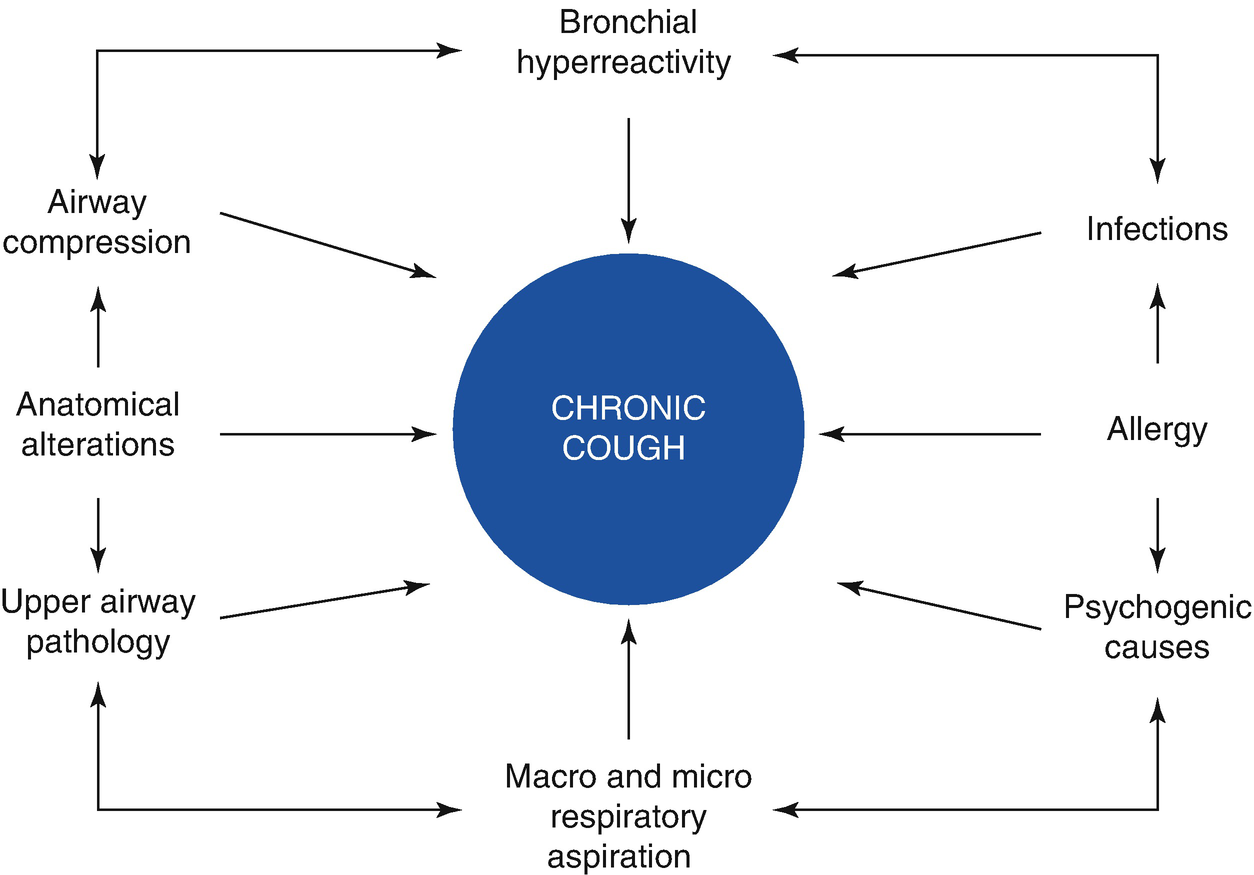

Interaction of etiological factors in chronic cough

The cause of cough can vary according to age. In infants, cough in early life suggests the presence of congenital anomalies such as a tracheoesophageal fistula, vascular ring, innominate artery, neuromuscular disorders, or other abnormalities or malformations of the airways. Viral infections such as Chlamydia, Bordetella pertussis, mycobacteria (tuberculosis), and others should not be ignored, nor should the possibility of gastroesophageal reflux (GER), cough-equivalent asthma, or cystic fibrosis.

In preschool children, upper airway cough syndrome (UACS) —including rhinosinusitis, adenoiditis, infection, and inflammation of Waldeyer’s lymphatic ring—and the effects of cigarette smoke (passive smoking) are added to the aforementioned range of causes. This is one of the periods of life when the possibility of asthma (cough-variant asthma) is particularly important. Cough caused by inhalation of a foreign body is typically paroxysmal but can be delayed and become chronic. Prolonged bacterial bronchitis , described above, is characterized by chronic productive cough caused by Moraxella catarrhalis, Haemophilus influenzae, or Streptococcus pneumoniae. It produces intense neutrophilic inflammation in the airways and characteristically resolves within 2 weeks of administration of amoxicillin and clavulanic acid or clarithromycin acid.

Causes of chronic cough by age

Infant | Preschool | School and adolescence |

|---|---|---|

Congenital anomalies Tracheoesophageal fistula Vascular ring Airway malformation Neuromuscular disorders Infections Viral Bacterial Tuberculosis Chlamydia Asthma Gastroesophageal reflux Cystic fibrosis | Infections Bacterial Viral Mycoplasma Tuberculosis Rhinosinusitis Asthma Gastroesophageal reflux Foreign body Irritative Passive smoking Cystic fibrosis Bronchiectasis | Asthma Rhinosinusitis Psychogenic Gastroesophageal reflux Infections Tuberculosis Mycoplasma Bronchiectasis Irritative Environmental pollution Smoking |

Diagnosis

- 1.

The clinical history (interview and physical examination) is the fundamental diagnostic pillar.

- 2.

Confirmation of a cause does not necessarily mean that it is responsible for the cough.

- 3.

The sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, and negative predictive value of the different diagnostic methods should be adequately considered.

- 4.

A diagnostic test is accurate only if the cough is resolved with the specific therapy for that diagnosis.

- 5.

Complementary studies should always be supported by the clinical history.

Symptoms and signs associated with specific causes of chronic cough in childhood

Symptom/sign | Possible etiology |

|---|---|

Pulmonary auscultatory findings | Asthma, bronchitis, foreign body, aspiration, congenital anomalies, cystic fibrosis |

Heart murmur | Heart disease |

Chest pain | Asthma, pleurisy |

Thoracic deformity | Severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease |

Productive cough | Chronic bronchitis, suppurative lung disease, cystic fibrosis |

Nail clubbing | Suppurative lung disease, cystic fibrosis |

Dyspnea on exertion/at rest | Airway or lung parenchymal disease, heart disease |

Growth retardation | Severe lung or heart disease, cystic fibrosis |

Deglutition disorders | Gastroesophageal reflux, primary aspiration |

Immunodeficiency | Suppurative lung disease, atypical infections |

Recurrent pneumonia | Immunodeficiency, congenital anomalies of the lung, tracheoesophageal fistula |

Fever | Tuberculosis, suppurative lung disease, bacterial bronchitis, other infections |

Hemoptysis | Suppurative lung disease, vascular anomalies, bronchitis |

In particular, consideration should be given to infants’ neonatal and feeding history, any habits relating to putting foreign objects in the mouth, and the personal and family background in relation to allergies. The pediatrician should review the history of vaccinations, irritants, and allergies at home and the prescribed medications: the dosages, durations of treatment, adherence, and responses to medication. The use of angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors should be investigated.

Asthma-associated cough is typically nocturnal and exacerbated by cold air, irritants, allergens, and exercise. Cough can be the only manifestation for a long period and can delay a definitive diagnosis. Knowledge of the personal and family history of atopy can be orienting.

A chronic cough associated with purulent expectoration indicates bronchiectasis, suppurative pulmonary, or cystic fibrosis. An association with chronic diarrhea, slow growth, nasal polyposis, and/or nail clubbing provides strong evidence of cystic fibrosis.

Postnasal discharge in children often indicates nasal obstruction and mucopurulent rhinorrhea. Persistent headaches and eventually facial pain and pain around the eyes are symptoms suggestive of sinusitis, while a history of recurrent febrile syndrome, with general malaise and generally productive cough, indicates the need to inquire about contacts and raises suspicion of tuberculosis.

Cough can be linked in aspiration syndromes to regurgitation and choking, and can be exacerbated during or after eating. Occasionally, wheezing and basal crackling can be heard. Finally, psychogenic cough is unproductive, relaxes while the subject is sleeping, and does not improve with antitussive drugs. It is usually diagnosed by a process of elimination.

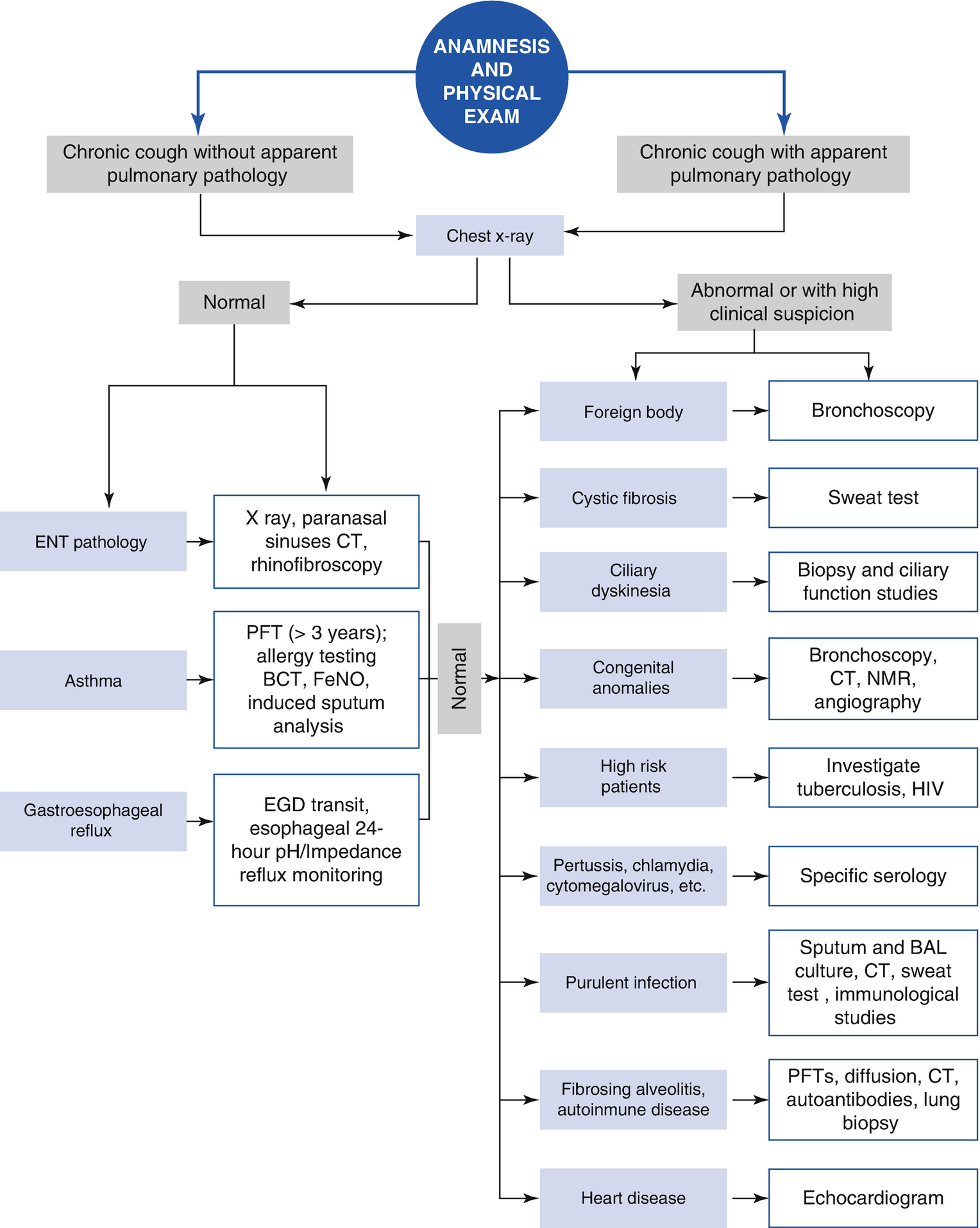

The pediatrician should carefully consider complementary studies, which will depend on the initial clinical assessment. A chest x-ray is the first indicated study and should be done in almost all cases. It can confirm the existence of an organic pulmonary cause of cough, and it is the guide for an algorithm of subsequent complementary studies. If the chest x-ray is abnormal—for example, if it shows the presence of localized shadows or diffuse infiltrates—more complex imaging techniques, cultures, sputum cytology, and/or diagnostic bronchoscopy should be employed.

In children under 3 years of age, spirometry can contribute to detection of reversible bronchial obstruction, which is compatible with a diagnosis of asthma. If the results are normal, with a strong suspicion of asthma, a bronchial provocation test with either exercise or methacholine, and an airway inflammation study measuring exhaled nitric oxide or induced sputum, are indicated if they are available. The sensitivity and specificity of the method that is employed should be considered in order to optimize the diagnostic utility.

X-rays of the paranasal sinuses offer low diagnostic specificity, but it improves significantly when combined with clinical findings for etiological determination of cough syndromes associated with upper airway pathologies (UACS). Computerized tomography is not generally recommended to assess sinusitis, although it can provide more diagnostic precision.

Rhinopharyngeal assessment can contribute to detection of organic pathologies of the upper airway and provide indirect signs of a laryngopharyngeal reflux that is responsible for cough. An esophagogastroduodenal transit study allows us to study GER, foreign bodies in the esophagus, tracheoesophageal fistulas, and exogenous compressions of the esophagus. GER and/or laryngopharyngeal reflux should be suspected in all cases of cough with an undetermined cause. In this respect, 24-hour esophageal pH monitoring may be useful, although a normal study does not rule out nonacid reflux as a cause of associated cough, which can be detected by impedance measurement.

Allergological assessment (skin tests for immediate detection of allergens, immunoglobulin dosages, etc.) should be reserved for specialist use for proper interpretation.

A study of tuberculin sensitivity is absolutely necessary if epidemiological evidence of tubercular contacts is found, including the entire family if necessary.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree