Wet Gangrene

SALVATORE DOCIMO Jr and ANIL HINGORANI

Presentation

A 68-year-old female presents with a chief complaint of pain located within the right foot. The pain is accompanied by a dark discoloration of toes two, three, and four, with an area of erythema that is migrating proximally. The first and fifth toes were amputated previously. The pain is constant, and the dark discoloration has worsened over the last 2 weeks. Her comorbidities include type II diabetes mellitus for 18 years, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and a right femoropopliteal bypass with polytetrafluoroethylene graft 7 years ago. Her medications include hydrochlorothiazide, simvastatin, aspirin, and metformin. She uses alcohol socially and smokes half a pack of cigarettes daily for 25 years.

She is afebrile with vital signs within normal limits. Examination of the lower extremities demonstrates a left and right femoral pulse at 2+. No posterior tibial or dorsalis pedis pulses were palpable in either foot. No ulcerations of the left foot were noted.

Examination of the right lower leg reveals a lack of hair and rubor to the foot. A strong, foul odor emanating from her right lower extremity was noted. The first toe amputation site was noted to be dark and ischemic. The second and fourth toes were also noted to be dark and ischemic. The third and fourth toes were found to be swollen, cool, and cyanotic and noted to have capillary refill of 4 seconds. Figures 1 to 3 demonstrate the findings found on examination. The foot was found to be cool and erythematous, with blistering of the skin. Purulent material was expressed from the underside of the toes upon palpation.

Laboratory testing demonstrated a white blood cell (WBC) count of 8.0 K/UL, a normal hemoglobin and hematocrit, and a normal chemistry panel.

FIGURE 1 Wet gangrene of the right lower extremity. Medial view. Note the edematous and erythematous tissue proximal to the necrotic tissue.

FIGURE 2 Dorsal view of a right lower extremity with wet gangrene. Note the previous amputation of the hallux. Aspects of wet gangrene, such as edema, erythema, and necrotic tissue are present.

FIGURE 3 Wet gangrene of the right lower extremity. Note the previous amputation of the hallux.

Differential Diagnosis

Dry Gangrene

Gangrene can be classified as dry or wet. Dry gangrene is often seen in patients with diabetes and atherosclerotic disease due to their diminished arterial flow. The decreased arterial flow creates ischemic, nonviable tissue, which becomes dry and at times dark. There is a lack of putrefaction. Another rare cause of dry gangrene is venous in origin. Venous gangrene occurs through the final phases of phlegmasia alba dolens and phlegmasia cerulea dolens.

Wet Gangrene

Wet gangrene involves putrefaction of tissue. Wet gangrene can progress from dry gangrene as the necrotic tissue becomes infected. Wet gangrene is accompanied by edematous, erythematous tissue surrounding the necrotic area. Infection itself can also directly lead to wet gangrene without the presence of prior ischemia. Mild erythema surrounding an area of dry gangrene does not constitute wet gangrene.

Necrotizing Fasciitis

Necrotizing fasciitis involves a rapidly spreading infection involving the subcutaneous tissue and deep fascia, which tends to spare the overlying skin initially. Edema and severe pain are often noted as the infection progresses and undermines the skin. Fluid-filled vesicles may appear, which is often followed by a brown to bluish skin discoloration and eventually gangrene. Numbness sets in due to destruction of the cutaneous nerves. The pathogens responsible include anaerobic organisms (Bacteroides, Peptostreptococcus), facultative organisms (streptococci, E. coli, Klebsiella, or Streptococcus aureus), or a single organism such as S. pyogenes.

Gas Gangrene

Gas gangrene is a form of wet gangrene most commonly caused by the exotoxin-producing Clostridium perfringens. Also known as “myonecrosis,” the bacteria proliferate in the necrotic tissue and release exotoxin, known as alpha toxin, which further damages surrounding tissue, providing further nutrients for the anaerobic bacteria. The diagnosis is based upon the physical findings of infection with air in the soft tissues or crepitus. It is not based upon the finding of air on radiologic studies alone as this may not be associated with infection of the soft tissues. Treatment is urgent source control with surgical debridement and broad-spectrum antibiotic coverage.

Diagnosis

Overall, the diagnosis of wet gangrene is clinical and based upon the physical examination. Wet gangrenous tissue will have a combination of characteristics that include edema, erythema, pungent smell, blisters, purulent discharge, and necrotic tissue. These findings are pathognomonic and confirmative for diagnosing wet gangrene. Prompt surgical and medical intervention should not be delayed in order to obtain radiographic studies.

In the setting of wet gangrene, analysis of the arterial system is not indicated prior to source control. Noninvasive analysis, such as duplex scanning and the calculations of the ankle-brachial index (ABI) and toe-brachial index (TBI) are indicators of limb perfusion but do not play a vital role in the initial management of wet gangrene. More invasive studies, such as angiograms, can be also utilized to evaluate the arterial supply but only following source control.

Imaging, such as x-rays, may demonstrate changes associated with osteomyelitis such as soft tissue swelling, subperiosteal elevation, and sequestra or pieces of dead bone created during the process of necrosis leading to osteomyelitis. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is the gold standard used to differentiate necrotizing soft tissue infections from nonnecrotizing cellulitis, with a sensitivity of nearly 100%. However, in the setting of wet gangrene, these studies are rarely indicated.

Approach to Management

Surgical Management

In the setting of wet gangrene, the only treatment option is source control with debridement and possible amputation. The timing of intervention will depend on the degree of pain, systemic toxicity, the presence of myoglobinuria, and extent of renal injury. Determination of amputation level is primarily based upon physical examination and also intraoperative findings. Intraoperatively, tissue will be removed until viable tissue is appreciated. Clinical judgment alone results in adequate healing of the stump in 80% of below-knee amputations and 90% of above-knee amputations. Repeated exams of the wound are necessary as repeat debridements may be needed.

In the setting of wet gangrene, broad-spectrum perioperative antibiotics should be administered. Anaerobic coverage in diabetic patients is recommended. A two-stage amputation involving a guillotine amputation followed by a definitive closure at a later stage may be an option.

Medical Management

Medical management often focuses on the prevention of ischemia leading to gangrene. Once gangrene has occurred, treatments often include pain relief, local ulcer care and pressure relief, treatment of infection, and modification of atherosclerotic risk factors, and also revascularization. Patients with peripheral artery disease should be receiving aspirin, beta-blockers, and statins—all shown to lower cardiovascular morbidity and mortality. Tight control of glucose levels to avoid hyperglycemia will also reduce the incidence of wet gangrene.

Wound care is based upon the tenets of adequate perfusion to the ischemic limb, adequate nutrition, and controlling infection. Surgical debridement of infected wounds or necrotic tissue is often required before healing can proceed. Hydrotherapy, vacuum-assisted closure, hyperbaric oxygen therapy, and wound dressing changes can also assist in wound healing after source control.

Discussion

Understanding the various types of gangrene and how to diagnose each are of vital importance.

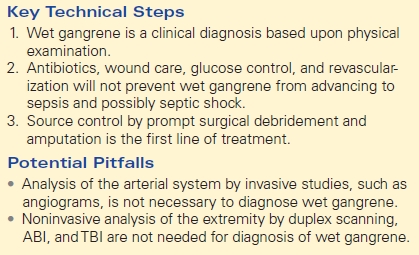

Wet gangrene, a pathology requiring clinical diagnosis, is an ominous sign for amputation. Source control by way of debridement, with or without amputation, can prevent proximal progression and negate the risk of septic shock. Any other means of treatment, such as antibiotics, wound care, strict glucose control, or revascularization alone, will not prevent wet gangrene from advancing to sepsis and eventually septic shock (Table 1).

TABLE 1. Key Technical Steps and Potential Pitfalls