15

Wegener’s Granulomatosis

Wegener’s granulomatosis (WG) is a multisystem disorder with aseptic necrotizing granulomatous inflammation associated with vasculitis that primarily affects the upper and lower respiratory tract and kidney. WG is a rare disease affecting 0.3 person/1 million in the United States and 8.5/1 million in the United Kingdom.1–5 There is a slight male predilection for the disease, with a mean age of ~50 years, but a wide range extending from the pediatric population to the elderly. Symptoms of WG are protean and therefore there is often significant time lost in obtaining the diagnosis in this condition. The disease most commonly affects the head and neck region, with nearly 75% of patients showing some manifestation at the time of presentation, usually rhinorrhea, earache, sinus pain, pseudotumor of the orbit with proptosis of the eye, and, in a minority of cases, nasoseptal collapse with saddle nose deformity.3 Pulmonary diseases are noted in ~45% of patients at the time of presentation, although over 75% of patients show evidence of pulmonary symptoms at some time during their clinical course.3,5 Pulmonary disease is often accompanied by systemic symptoms of fever, malaise, fatigue, and arthralgias, whereas specific pleuropulmonary manifestations include cough, hemoptysis, chest pain, and pleuritis. In the pediatric population, tracheal stenosis and stridor are common presenting findings. Kidney disease is noted at the time of presentation in ~20% of cases, and manifests as hematuria with red cell casts and renal failure.3,4

In patients with pulmonary disease, radiographs demonstrate multifocal pulmonary opacities, which evolve over time into nodules 0.5 to 10 cm in diameter, with a lower lobe predilection.6,7 Cavitation is noted in 25 to 50% of patients with the cavities displaying thick walls with irregular margins.3,6 Some nodules are wedge shaped like pulmonary infarcts and are suspected to be a consequence of vasculitic involvement of large muscular pulmonary arteries. Other nodules have a ground-glass opacity surrounding the nodule (halo sign), reflecting alveolar hemorrhage around the inflammatory nodules.6 Along with this finding are “stellate” arteries, which are said to be a manifestation of vasocentric inflammatory injury.6,7

Pulmonary function studies are not terribly helpful in this condition in that they show both restrictive and obstructive patterns. It is essential with the physiologic studies, however, to make sure that the obstruction is not a result of laryngotracheal stenosis.

There are several special manifestations of this protean disease, which are worthwhile highlighting. First, WG can affect the pediatric population, and in one study children comprised 15% of the WG study group.3 Second, although radiographs typically demonstrate multiple nodules in the lungs, there are reports of WG presenting as a solitary nodule.8 Third, Carrington and Liebow9 popularized the concept of “limited” forms of WG. It is clear that only a minority of patients with WG present with the classic triad with involvement of the upper and lower airways and kidneys.10 In fact, it is much more common for either one or two sites to be involved. Consequently, the concept of limited WG has been translated by some to refer to WG in which involvement is localized to a single organ system, usually lung. More recently limited WG has been defined as a condition that satisfies the diagnostic criteria as outlined by the American College of Rheumatology in the absence of any features posing immediate threats to either a critical individual organ or to the patient’s life (e.g., acute renal failure or severe hypoxemia).11 Using this definition, patients with limited disease tend to be younger, are more likely to be women, and have a higher prevalence of destructive upper respiratory tract disease at presentation. Fourth, the initial descriptions of Wegener’s indicated a median survival of 5 months, with death of nearly all patients within 2 years.12 Although the perception that such a fulminant course is common in WG, Fienberg13 has long emphasized the “protracted superficial phenomenon” of WG. Specifically, this concept indicates that WG can fester at a single site of involvement for many years, up to 18 years in some cases without progression to other organ systems. Such chronic disease may remain the characteristic pattern in an individual, but evolution to a more rapid clinical course must be monitored.

The clinical workup of a WG usually reveals anemia in up to 50% of patients.1–4 This is often accompanied by a leukocytosis, thrombocytosis, and an elevated sedimentation rate. Rheumatoid factor is present in ~50% of patients, and 25% of patients show evidence of circulating immune complexes.1–4

Antineutrophil Cytoplasmic Antibodies (ANCAs)

Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies ANCAs are autoantibodies directed against the cytoplasmic constituents of neutrophils and monocytes, particularly the azurophilic granules of neutrophils.13–24 Indirect immunofluorescence was first used to detect serum ANCA, and based on the microscopic examination of a variety of fluorescent patterns, two distinct forms of ANCA are identified: cytoplasmic-staining antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (c-ANCA) and perinuclear- staining antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (p-ANCA). c-ANCA reflects the presence of antibodies to proteinase 3, a 29 kilodalton serine proteinase found in the lysosomes and plasma membranes of neutrophils and monocytes. With indirect immunofluorescence, this form of ANCA assumed a coarse granular pattern with central interlobular accentuation within neutrophils when the patient’s serum was applied to normal neutrophils fixed on a glass slide. p-ANCA is a reflection of an artifact of ethanol fixation of substrate neutrophils, which results in fragmentation of the positively charged proteins of the neutrophil granules, which then migrate to the negatively charged nuclear chromatin. p-ANCA is most often directed at myeloperoxidase, although the p-ANCA pattern may also be seen with autoantibodies directed at elastase, cathepsin B, lactoferrin, and lysozyme.25 On immunofluorescence, the pattern of staining reveals accentuation of the lobular configuration of the neutrophil nucleus. Atypical forms of ANCA positivity have also been observed.25 However, their endogenic specificities are poorly defined.

c-ANCA usually signifies the presence of autoantibodies directed against proteinase 3, and anti–proteinase 3 autoantibodies are in turn strongly associated with WG. In patients with systemic WG, c-ANCA has been reported in 85 to 95% of cases; in localized WG between 50 and 70%, and when in remission between 30 and 40%.26,27 Approximately 10 to 20% of cases of WG lack the presence of c-ANCA.28 Although c-ANCA is highly sensitive and specific for WG, it should not be used as the sole criteria for making this diagnosis. In part, this is because c-ANCAs have also been reported in patients with connective tissue disorders, especially rheumatoid arthritis, and inflammatory bowel disease, particularly ulcerative colitis, infection, malignancy, and thromboembolism.22,29 It should also be noted that there is no distinct morphologic differences in cases of WG that have c-ANCA or p-ANCA, the latter occurring in 5 to 20% of WG cases.30–32 c-ANCA, however, is worthwhile utilizing in monitoring the patient’s disease in that relapses often are preceded by an increase in ANCA levels.3,24 This has led to debate as to whether patients with rising ANCA levels with a known diagnosis of WG should be treated. Most investigators today believe that only 50% of patients with rising ANCA titers actually undergo relapse; therefore, treatment based solely on titer alterations is not recommended. p-ANCAs are autoantibodies that have associations with microscopic polyangiitis, Churg-Strauss syndrome, polyarteritis nodosa, and rapidly progressive pauci-immune glomerulonephritis.

Recent studies have shown that ANCAs can be isolated from bronchoalveolar lavage fluid, suggesting that the bronchial-associated lymphoid tissue may be one source of their production.33–35

The direct immunofluorescence for the assessment of ANCAs has also been altered more recently by solid-phase assays such as enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), focused specifically on the proteinase 3 and myeloperoxidase antigens. The morphologic patterns of pulmonary inflammation associated with these autoantibodies has also been studied, and although WG is the dominant pattern, other patterns of pulmonary inflammation, such as cryptogenic organizing pneumonia, diffuse alveolar damage, and nonspecific interstitial pneumonia, have been well described.31

Despite the nonspecific nature of c-ANCA, particularly with regard to false-positive tests, c-ANCA is tremendously helpful in the clinical setting of suspected WG. It provides confirmatory evidence of morphologic observations. A negative C-ANCA test should be a cause for reassessment of biopsy findings, although it should not sway one from a diagnosis of WG. Repeat testing also may reveal positive studies at a different point in the patient’s clinical course.

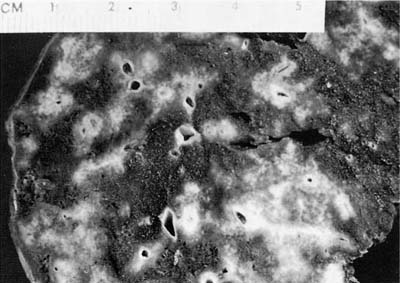

FIGURE 15–1 Granulomatous necrosis in pulmonary Wegener’s granulomatosis (WG) is seen as punctuate gray foci around vessels and airways and scattered through the parenchyma. Such small foci of necrosis represent early necrotic granulomas, which coalesce to form the large geographic zones. (Courtesy of Dr. Andrew Churg, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada.)

Gross Appearance

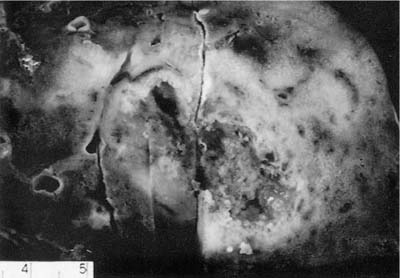

The nodules of WG range in size from 0.3 to 12 cm with an average size of 2.4 cm (Fig. 15–1).6,7,35 As noted previously, between 25 and 50% of nodules undergo cavitation. The central cavity is often hemorrhagic and necrotic whereas the margins of the cavity are irregular and shaggy (Fig. 15–2). The borders are frequently yellow, reflecting the presence of an inflammatory cell infiltrate and prominent lipid-laden macrophages.

Histopathology

As described, WG is a clinicopathologic entity with a wide spectrum of clinical and radiographic features. This heterogeneity is also reflected in the histopathologic manifestations of this disease. Pathologic criteria for diagnosing WG in biopsies from the lung and head and neck emphasize a variety of different features, each of which could represent the dominant pattern in the biopsy specimen.36–38 From a general perspective, there are three morphologic components of the lesions of WG:

FIGURE 15–2 Pulmonary WG showing a cavitated mass. The center of the cavity is irregular and necrotic and surrounded by a thick, consolidated rim of lung tissue.

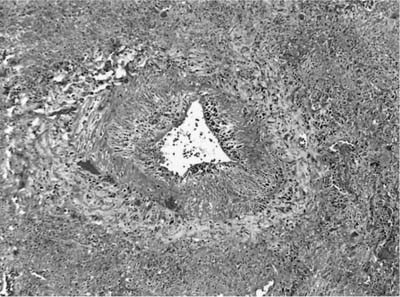

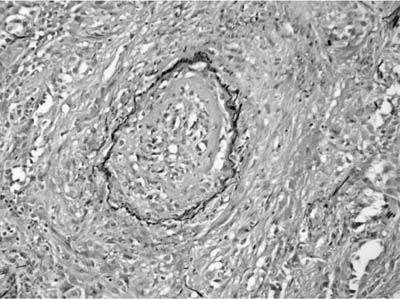

FIGURE 15–3 Vasculitis in WG affects arteries and veins. In this instance, a large vein shows marked mural necrosis by a palisaded granulomatous reaction with destruction of the muscular wall.

1. Vasculitis

2. Parenchymal necrosis with granulomatous inflammation

3. Inflammatory background with or without a granulomatous component

The presence of vascular injury in the form of vasculitis is an essential component of WG, although its presence is not required to make this diagnosis. The vasculitis affects arteries, arterioles, veins and venules, and capillaries. In the larger vessels, the earliest lesion is a subendothelial infiltrate of neutrophils, eosinophils, lymphocytes, and monocytes that migrate into the vessel wall and are associated with mural necrosis (Figs. 15–3, 15–4, and 15–5). The injury to the vessels is segmental and focal and is associated with destruction of the vascular elastica (Fig. 15–6). Although fibrinoid necrosis of vessels is reported, its presence in Wegener’s disease is infrequent. With time, the inflammatory infiltrate assumes a more granulomatous component with fragments of elastic tissue engulfed by inflammatory cells, especially histiocytes and giant cells. The vasculitis is often noted within the dominant inflammatory nodule. Vasculitis outside of this nodule is infrequent and is not required to make the diagnosis; in fact, waiting to find this feature may delay diagnosis and risk patient morbidity and mortality.

FIGURE 15–4 Muscular arteries in WG are initially affected by a subendothelial chronic inflammatory cell infiltrate, which may be circumferential or segmental and is associated with damage to the muscular wall of the arteries. This inflammatory infiltrate may be lymphocytic, leukocytoclastic, granulomatous, or mixed.

FIGURE 15–5 Small vessel disease in WG is difficult to identify. This arterial has a subendothelial neutrophilic infiltrate with vessel injury associated with adventitial monocytic cells and rare giant cells, reflecting the evolution of a granulomatous vasculitis.

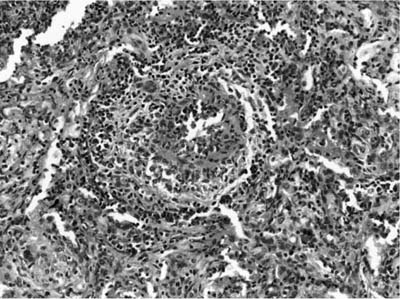

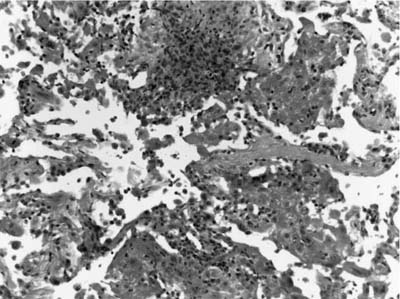

Pulmonary capillaritis is a common finding in WG both within the inflammatory nodule and at its periphery. It consists of a region of alveolar septal necrosis induced by an infiltrate of neutrophils within the alveolar septum (Figs. 15–7 and 15–8). This infiltrate is accompanied by fibrin thrombi within alveolar septal capillaries and necrosis of the alveolar septum, with fragments of neutrophils, hemorrhage, and fibrin exploding from the septum in a radial fashion. A unique finding in Wegener’s disease is the evolution of a granulomatous reaction around this necrotic alveolar septum with the influx of monocytes and T cells, which arrange themselves in a peripheral fashion around the destroyed capillary (Figs. 15–9, 15–10, and 15–11). Conversion of this infiltrate to epithelioid histiocytes and giant cells is noted as a small microabscess/necrotic focus evolves and enlarges to form a zone of necrosis and cavitation (Fig. 15–12).

FIGURE 15–6 Elastic tissue stains can highlight the vessel injury in WG by identifying the circumferential elastica of veins and arteries.

FIGURE 15–7 Pulmonary capillaritis is often seen in the setting of alveolar hemorrhage. Within the hemorrhage, small punctate areas of neutrophilic aggregation are a clue to the presence of capillaritis.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree