63 Volume and Outcome

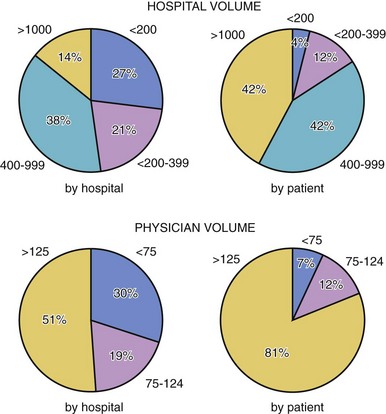

A series of studies over 30 years have repeatedly identified a relationship between increased procedural volume and lower mortality, particularly for higher-risk procedures or patients.1–11 The finding of better outcomes with increased experience seems rather obvious and, in isolation, should not engender much controversy. When the volume–outcome relationship is applied to health policy in a manner that suggests that patients should avoid low-volume hospitals or physicians, passionate debate ensues. Fueled by intense policy interests, papers that support or refute volume standards continue to be published in the medical and health services research literature. This chapter will examine the volume–outcome relationship for PCIs in depth according to the strength of the evidence and the underlying reasons why study conclusions may vary despite the consistency of the relationship. On the basis of this review, a practical framework for public policy will be proposed. To provide some perspective on the issue, one must first understand that the proposed volume thresholds represent very low numbers and impact relatively few patients. The relationship between worse outcome and low volume is most apparent among the very-low-volume operators. In the case of interventional cardiologist volume, an overall PCI volume of 75 cases per year requires performance of fewer than two procedures per week, and a primary PCI volume of 12 involves treatment of one ST elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) per month. A hospital must perform 4 cases per week to reach a threshold of 200 elective PCI cases, and 3 cases per month to reach a primary PCI threshold of 36 cases. With such low thresholds, low-volume providers treat relatively few patients. A reasonable gauge of the relative proportion of patients treated in low-volume institutions can be obtained from the National Inpatient Sample (NIS), a nationally representative cohort of patients of all ages treated at 20% of the U.S. hospitals.1 Data from the NIS indicate that only 4% of patients undergoing PCI are treated in hospitals with volumes below 200 cases per year, yet the low-volume institutions treating these relatively few patients represent 27% of hospitals (Fig. 63-1). Similarly, extrapolating physician volumes from the New York State Coronary Angioplasty Reporting System, 7% of patients are treated by physicians who perform fewer than 75 cases per year, and these operators represent 30% of all physicians performing PCI.

Figure 63-1 Distribution of percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) volume by hospitals, physicians, and patients.

Evidence for a Volume–Outcome Relationship

Evidence for a Volume–Outcome Relationship

The origins of the volume–outcome relationship date back to 1979 when Luft, Bunker, and Enthoven of Stanford University identified higher mortality at lower-volume hospitals for a number of surgical procedures, including open heart and vascular surgeries.2 Of 12 surgeries, the relationship was most evident among the higher-risk procedures, and their initial data identified a threshold of approximately 200 surgical procedures above which procedural mortality decreased by 25% to 41%. In their initial work, the authors suggested that the observed relationships supported the regionalization of higher-risk procedures. Since the initial work, the volume–outcome relationship has repeatedly been demonstrated for a number of procedures and conditions, most recently by Ross et al.12 Examining over three million Medicare patients hospitalized at 4679 hospitals between 2004 and 2006 for acute myocardial infarction (AMI), congestive heart failure (CHF), or pneumonia, those treated at lower-volume hospitals had significantly higher 30-day mortality rates. For AMI, the upper volume threshold was 610 cases, beyond which significant differences in mortality were no longer observed.

Volume standards for PCI were first introduced in the 1988 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) guidelines.13 Lacking empirical evidence for coronary angioplasty volume, the task force selected the threshold volume of 50 cases based on the rationale that one must golf about once per week to remain proficient and that such an experiential relationship likely extended to PCIs. The publication of this standard unleashed a flood of concerns from approximately half the cardiologists performing angioplasty at the time who did not meet the one-case-per-week standard. Providers opposed to volume standards were concerned about restrictions to practice in the absence of empirical evidence of a volume–outcome relationship for PCI. They were also concerned that such standards may impede high-quality but low-volume physicians and that annual volume standards did not take into account aggregate experience over a number of years.

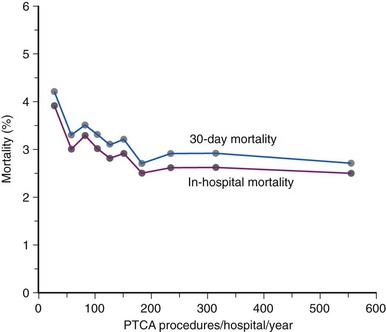

Empirical evidence supporting a volume–outcome relationship for PCI began to emerge in the 1990’s. In a study of Medicare procedures, Jollis et al found in-hospital mortality increasing from 2.5% for high-volume hospitals to 3.9% for those treated at low-volume hospitals.3 Among the 217,836 patients studied, the relationship between volume and outcome appeared “J” shaped, with the highest mortality for hospital volumes at below 100 Medicare procedures per year (Fig. 63-2). As Medicare primarily involves patients over age 65 years, a Medicare case volume of 100 represents an overall hospital volume of roughly 200 cases per year. For 19,594 patients undergoing elective PCI in 48 hospitals in the Society for Cardiac Angiography and Interventions registry, Kimmel found significantly higher mortality, emergency bypass, and major complications for patients treated at hospitals with volumes below 400 cases per year.4 In the New York State Coronary Angioplasty Reporting System, Hannan et al identified significantly higher risk-adjusted mortality for patients treated at hospitals with annual volumes below 600.5 Following the widespread adoption of coronary stents, repeat analyses of Medicare data by McGrath et al continued to identify higher mortality for low-volume hospitals.

Figure 63-2 Mortality for Medicare beneficiaries according to hospital volume.

(Data from Jollis JG, Peterson ED, DeLong ER, et al: The relation between the volume of coronary angioplasty procedures at hospitals treating Medicare beneficiaries and short-term mortality, N Engl J Med 331:1625–1629, 1994.)

Evidence for a relationship between physician volume and outcome also emerged in related analyses, with both Jollis and Hannan identifying higher in-hospital mortality for physician volumes below 75 cases per year.5,6 Thus, with substantial compelling evidence, the PCI guidelines revised the minimum volume standards upward to 75 cases per year for physicians and 200 cases per year for hospitals.14

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree