Ventricular Arrhythmias

Prabhat Kumar

Jagmeet Singh

Ventricular arrhythmias (VAs) are often encountered in intensive care settings. Patients presenting to the emergency room with VAs are often admitted to the cardiac care unit (CCU) for observation and evaluation. It is important to make a quick diagnosis of this arrhythmia and provide a prompt therapy to improve survival in this patient group. If not treated on time, VA may leads to deterioration of clinical status or a fatal outcome, depending on the hemodynamic compromise produced by the arrhythmia. Prevention, prompt detection, and early treatment of VA are important factors in favorable CCU survival.

CLASSIFICATION OF VENTRICULAR ARRHYTHMIA

The spectrum of VAs ranges from isolated ventricular premature complexes to ventricular tachycardia (VT) and ventricular fibrillation.1 All these types may be a cause for concern or have clinical effects in a given clinical context.

Premature ventricular complexes (PVCs) are isolated complexes originating in the ventricle dissociated from the atrial activity. As the QRS complexes are of ventricular origin, ventricular depolarization does not occur through the His-Purkinje system leading to wide QRS complexes, with notable exceptions of origin in proximal His-Purkinje system. There may be a fusion of these complexes with conducted beat from the atrium.

Couplets and nonsustained VT may be more important as these may suggest higher chances of occurrence of sustained VT and/or ventricular fibrillation.

Frequent PVCs and frequent nonsustained VT may lead to clinical deterioration in the presence of compromised left ventricular function or ongoing ischemia.

Accelerated idioventricular rhythm (AIVR) is a specific kind of automatic slow ventricular rhythm at a rate of 60 to 100 beats per minute (bpm). This is incited by factors such as ischemia, cardiomyopathy, and some drugs.

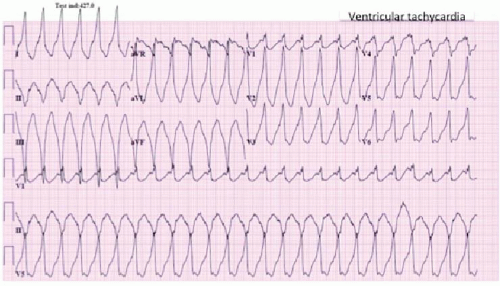

VT is defined as three or more consecutive beats of ventricular origin at a rate >100 bpm (Figure 17.1).

VT is called sustained VT if it continues for at least 30 seconds or causes hemodynamic compromise requiring termination within 30 seconds.

VT lasting for <30 seconds and not causing hemodynamic compromise is classified as nonsustained VT (NSVT).

VT is categorized as monomorphic if all the ventricular complexes are similar.

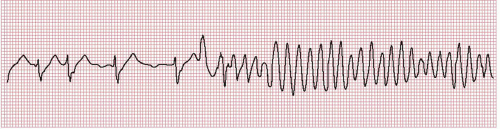

Polymorphic VT has changing QRS morphology, as opposed to monomorphic VT with constant QRS morphology. Torsades de pointes is a type of polymorphic VT with QRS complexes of changing amplitude that appear to twist around the isoelectric line (Figure 17.2).

Bidirectional VT is a specific type of VT seen in certain conditions (e.g., digoxin toxicity) and has alternating QRS axis in the consecutive beats.

Figure 17.2. Rhythm strip recorded at the onset of torsades de pointes. Note the pause-dependent initiation of tachycardia and prolonged QT interval in the preceding beats.

Ventricular fibrillation is a ventricular rhythm with ill-formed irregular ventricular complexes owing to chaotic electrical activity of ventricles at a high rate (>300 per minute).

ETIOLOGY

VENTRICULAR TACHYCARDIA/FIBRILLATION

VT/fibrillation has multiple etiologies. They can be classified into three sections:

Structural heart disease: Patients with structural heart disease are at a risk of developing VAs. These can be broadly grouped as below:

Ischemic heart disease: VA can be seen in patients with acute as well as chronic ischemic heart disease. Acute coronary syndrome with ongoing myocardial ischemia and acute myocardial infarction predispose the patients to VAs including PVCs, NSVT, and more malignant VT and ventricular fibrillation. Patients with chronic coronary artery disease (CAD) and with a history of myocardial infarction leading to myocardial scar are predisposed to scar-related VT, which is usually monomorphic. PVC and other forms of VA associated with acute ischemia are likely to be polymorphic.

Nonischemic cardiomyopathy: Various forms of nonischemic cardiomyopathy have the propensity to develop VAs. These include idiopathic dilated, hypertrophic, and arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy (ARVC).

Infiltrative cardiac diseases and myocarditis: Cardiac involvement with sarcoidosis is another cause of VA encountered in clinical practice. Various forms of myocarditis also have the potential of causing VAs, which at times may be clinically unstable.

Ventricular arrhythmias without structural heart disease: Many of these arrhythmias are considered to be owing to some defect in the handling of ions responsible for various phases of depolarization and repolarization of cardiac myocytes and conducting tissue of the heart. The exact molecular basis is not clear in some of these, which are categorized as idiopathic. Specific conditions in this group are as below:

Figure 17.3. A 12-lead ECG of a patient with Brugada syndrome. Note the characteristic ST elevation in the right precordial leads.

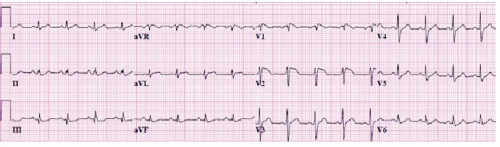

Brugada syndrome: This is a distinct syndrome seen frequently in south-east Asians, characterized by idiopathic ventricular fibrillation with presence of right bundle branch block (RBBB) pattern with ST-segment elevation in right precordial leads on baseline ECG (Figure 17.3).2 Mutation in the Na+-channel gene has been seen in many of the families with Brugada syndrome.3,4

Catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia: This is a rare form of inherited polymorphic VT caused by a mutation in the genes encoding ryanodine receptor and calsequestrin involved in handling calcium ion in the cells.5,6

Long QT syndromes: These are a group of inherited syndromes caused by mutation in ion channels regulating the repolarization of myocytes, which lead to prolongation of the QT interval. These cause a specific form of VT, torsades de pointes, with characteristic ECG pattern (Figure 17.2).7,8 The acquired form of long QT syndrome is caused by certain drugs (Table 17.1).

Idiopathic ventricular tachycardias: These are focal monomorphic VTs originating in the outflow tracts or left ventricular septum. These can be subcategorized into outflow tract tachycardia (RV outflow tract being a commoner site of origin than LV outflow tract), fascicular (originating in the left ventricular side of the interventricular septum), and rare RV inflow tachycardia.9 These probably have multiple mechanisms including reentry (fascicular VT) and triggered activity (outflow tract tachycardias and fascicular VT).9

Reversible noncardiac etiologies: VAs can be caused by certain factors leading to abnormal excitability of the myocardium.

Electrolyte abnormalities such as hypokalemia and hypomagnesemia can precipitate VAs.

TABLE 17.1 QT-Interval Prolonging Drugs Causing Torsades de Pointes

CARDIOVASCULAR

NEUROPSYCHIATRIC

Antiarrhythmic

Antipsychotics

Amiodarone

Chlorpromazine

Sotalol

Haloperidol

Ibutilide

Mesoridazine

Dofetilide

Pimozide

Procainamide

Thioridazine

Quinidine

Opiates

Disopyramide

Levomethadyl

Anti-anginal

Methadone

Bepridil

ANTIMICROBIAL

GASTRO-INTESTINAL

Antibiotics

Cisapridea

Macrolides

Domperidoneb

Clarithromycin

Droperidol

Erythromycin

ANTIHISTAMINES

Fluoroquinolones

Astemizolec

Sparfloxacin

Terfenadinec

Antiprotozoal

OTHERS

Pentamidine

Arsenic trioxide (anticancer)

Chloroquine

Probucolc

Halofantrine

a Restricted availability;

b Not available in the United States;

c No longer available in the United States. Source: http://www.QTdrugs. org; look at the website for complete list of drugs with possible and conditional risk of torsades de pointes.

Intracardiac leads may occasionally cause irritation of the myocardium initiating VAs.

Physiological stress in general can lead to a hyperadrenergic state predisposing to VAs. This may be a causative factor in patients admitted to the intensive care unit. Hypoxia, hypotension, and other physiological stress factors may be causative.

Drugs: Other causes of VT are pro-arrhythmic medications. A high degree of suspicion should be exercised for this etiology in evaluating a patient’s having VT, especially in patients admitted in the hospital on multiple medications. Certain drug interactions causing elevation of the serum level of pro-arrhythmic drugs should be kept in mind in these situations. Electrolyte abnormality can augment the pro-arrhythmic potential of a drug, for example, hypokalemia in patients on digoxin increases its arrhythmogenic potential.

These reversible factors can lead to VAs on its own, but they are even more likely to cause these arrhythmias in the presence of cardiac substrate abnormalities such as cardiomyopathy and ischemic heart disease. As can be seen, some of these have correctable factors and should be an important focus of management in these patients.

PREMATURE VENTRICULAR COMPLEXES AND NONSUSTAINED VT

Premature ventricular complexes and nonsustained VT also have similar etiologies as VT and ventricular fibrillation (VF). However, a large fraction of normal people can also have isolated infrequent PVCs, which have no significance in the absence of structural heart disease, if monomorphic.10,11 Polymorphic PVCs suggest multifocal origin and may suggest myocardial ischemia and need more urgent attention.12 The prognostic implication of NSVTs is dictated by the underlying myocardial substrate.11,13

ACCELERATED IDIOVENTRICULAR RHYTHM

As mentioned earlier, AIVR is seen in the setting of ischemic heart disease, cardiomyopathy, and drugs. In the setting of an acute coronary event, its occurrence has frequently been correlated with myocardial reperfusion, and this is considered to be a reperfusion arrhythmia.14

MANIFESTATIONS

PVCs may cause palpitations or a feeling of skipped beat in some patients, and it may remain asymptomatic in many. Hemodynamic deterioration may occur with PVCs if they are frequent. Frequent PVCs may lead to worsening of heart failure or worsening of myocardial ischemia and should be considered as a cause of worsening of heart failure or ischemia.

AIVR is usually a benign arrhythmia. However, in patients with compromised LV function, loss of LV synchrony may lead to hemodynamic deterioration leading to hypotension or heart failure. Patients with similar sinus rate may have rhythm switching between AIVR and sinus rhythm and may perceive the change in rhythm as palpitation.

NSVT such as PVCs have minimal symptoms of palpitations. However frequent NSVT such as frequent PVCs may exacerbate heart failure or myocardial ischemia.

VT may cause palpitations alone if hemodynamically stable. However, quite often VT is hemodynamically unstable and may cause heart failure, worsening of myocardial ischemia, syncope, or sudden cardiac death. Unstable VT if untreated usually degenerates into ventricular fibrillation.

Ventricular fibrillation always leads to cardiovascular collapse and loss of consciousness and unless promptly treated, leads to death.

DIAGNOSIS

Premature ventricular complex classically manifests a beat with QRS complex >120 milliseconds in duration, with a fully compensatory pause and absence of preceding P wave.

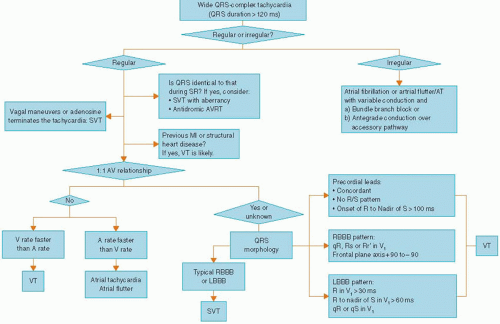

VT frequently manifests as wide complex tachycardia (QRS duration >120 milliseconds) on surface ECG. However, differentiation of such a wide QRS complex tachycardia from an SVT with aberrant intraventricular conduction is of paramount importance.

Various surface ECG criteria have been used to differentiate VT from SVT in the setting of wide complex tachycardia.

ECG CRITERIA FOR DIFFERENTIATION OF VT FROM SVT

Many EKG criteria had been developed for differentiation of VT from SVT.15

Fusion and capture beats and AV dissociation: These provide the strongest electrocardiographic evidence for differentiating VT from SVT with aberrant conduction. However in their absence, other clues from the ECG may be required to help with this differentiation.

Specific QRS contours can also be helpful in diagnosing VT:

Left-axis deviation.

QRS duration exceeding 140 milliseconds, with a QRS of normal duration during sinus rhythm.

In precordial leads with an RS pattern, the interval of the onset of R wave to the nadir of S wave exceeding 100 milliseconds suggests VT as the diagnosis.

Features supporting VT with an RBBB QRS morphology (predominantly positive QRS complex in V1):

A QRS duration of >140 milliseconds

The QRS complex is monophasic or biphasic in V1 with an initial deflection different from that of the sinus rhythm

The amplitude of the first r wave in V1exceeds r’ and

An rS or a QS pattern in V6.

Features supporting VT with a left bundle branch block (LBBB) type QRS morphology (predominantly negative QRS complex in V1):

A QRS duration of >160 milliseconds

The axis can be rightward, with negative deflections deeper in V1 than in V6

A broad prolonged (> 40 milliseconds) R wave can be noted in V1 and

A qR or QS pattern in V6.

A QRS complex that is similar in V1 through V6, either all negative or all positive, favors a ventricular origin. However, this is not very specific as an upright QRS complex in V1 through V6 can also occur from conduction over a left-sided accessory pathway.

In the presence of a preexisting bundle branch block, a wide QRS tachycardia with a contour different from the contour during sinus rhythm is most likely a VT.

Features supporting supraventricular arrhythmia with aberrancy:

Onset of the tachycardia with a premature P wave

A very short RP interval (100 milliseconds)

A QRS configuration similar to recorded supraventricular rhythm at a similar heart rate

P wave and QRS rate and rhythm suggest that ventricular activation is associated with atrial activation (e.g., an AV Wenckebach block) and

Slowing or termination of the tachycardia by vagal maneuvers. Exceptions include the outflow tract VT and the fascicular VT.

Specific QRS contours supporting the diagnosis of SVT with aberrancy are a triphasic pattern in V1, an initial vector of the abnormal complex similar to that of the normally conducted beats.

A wide QRS complex that terminates a short cycle length following a long cycle (long-short cycle sequence) may support SVT.

Atrial fibrillation with conduction over an accessory pathway should be suspected with grossly irregular, wide QRS tachycardia with ventricular rates >200 beats per minute.

Several algorithms for distinguishing VT from SVT with aberrancy have been suggested based on the ECG features mentioned above. One such algorithm is shown in Figure 17.4. All the above features have some exceptions, especially in patients who have preexisting conduction disturbances or preexcitation syndrome. Sound clinical judgment should always help in the decision based on ECGs in arriving at a diagnosis.

EVALUATION OF ETIOLOGY

REVERSIBLE FACTORS

Assessment should include serum electrolyte levels (particularly serum K+ and serum Mg2+ levels).

Presence of ongoing myocardial ischemia should be kept as a possibility.

Pro-arrhythmic drugs are important in the causation of PVCs in such a setting. Drugs that prolong the QT interval should be carefully screened. QT interval should be measured on the ECG routinely.

Any factor that may be instrumental in autonomic stimulation such as hypoxia, heart failure, surgical stress, and anesthesia, should be considered the potential cause.

EVALUATION OF ARRHYTHMOGENIC SUBSTRATE

Baseline 12-lead surface ECG can give clues to etiology of VAs. Conditions such as long QT syndrome (QTc >0.46 millisecond in male and >0.47 in female) and Brugada syndrome (Figure 17.3) may have characteristic baseline ECG pattern.

Because cardiomyopathies form almost 90% of all patients with VAs with sudden cardiac arrest, echocardiography is of great help in evaluating the substrate of these arrhythmias.16

Because a significant fraction (up to 50% in various series) of VAs is caused by CAD, stress evaluation is an important part of diagnostic workup. Stress test may involve stress ECG or stress imaging (echocardiography or SPECT). Stress test is also helpful in evaluating catecholaminergic polymorphic VT, with characteristic onset of VA with exercise.16

Cardiac MRI is of diagnostic value in evaluating ARVC besides delineating myocardial scars and evaluation of myocardial ischemia.16

Procainamide challenge is helpful in the diagnosis of Brugada syndrome.17

TREATMENT

The treatment plan of VAs can be divided into two parts, (1) acute treatment for ongoing arrhythmia and (2) chronic therapy for prevention of recurrence of arrhythmia and sudden cardiac death.

ACUTE THERAPY

Premature ventricular complexes and nonsustained ventricular tachycardia.

Any potential reversible factor should be corrected, for example, correction of electrolyte abnormality, withdrawal of causative drugs, treatment of myocardial ischemia with revascularization and repositioning of pacing leads.

Treating the basic condition, for example, correction of hypoxia and treatment of heart failure may control PVCs resulting from autonomic stimulation during various physiological stresses.

β-Blockers may be used to suppress frequent PVCs or episodes or NSVT causing exacerbation of heart failure or myocardial ischemia.18 Other antiarrhythmic drugs should be used with caution owing to their pro-arrhythmic potential and lack of effect on mortality and actually increased mortality in some situations.16

Accelerated idioventricular rhythm.

This rhythm is usually benign and need not be treated unless it leads to hemodynamic compromise.

If need for treatment arises, it can be done by increasing the sinus rate by administering atropine or isoproterenol or by atrial pacing.

VENTRICULAR TACHYCARDIA

Treatment of VT depends on whether the tachycardia is associated with hemodynamic compromise or not. If there is associated hypotension, heart failure, angina, or cerebral hypoperfusion synchronized DC, cardioversion should be done emergently. In the absence of decompensation, pharmacotherapy can be attempted.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree