Venous Disease

The spectrum of venous disorders ranges from unsightly (spider veins) to uncomfortable (varicose veins) to disabling (chronic venous insufficiency). Although many venous problems are chronic, thromboembolic events are acute and life-threatening. A solid understanding of the basic principles of venous disease can help the clinician effectively diagnose and treat these challenging patients.

I. Magnitude of the problem.

The magnitude of venous disease is widespread, with at least 15% of the U.S. population affected by simple varicose veins, and an even greater prevalence among women and the elderly. Another 5-10% are afflicted by chronic venous insufficiency, defined by skin changes in the leg related to prolonged venous hypertension in the deep and/or superficial venous system. Acute deep venous thrombosis (DVT) affects several hundred thousand people annually. A spectrum of postphlebitic syndrome, defined by symptoms of leg pain, edema, and/or ulceration, exists in all patients to some extent in the years following DVT. Pulmonary thromboembolism is a potential life-threatening consequence of untreated DVT, and is the most common preventable cause of death in hospitalized patients.

Chronic venous disease is classified by the CEAP grading system (Table 2.1), a standardized reporting method used worldwide. Four key features of venous disease are included: clinical signs, etiology (congenital, primary, or secondary), anatomic location (superficial, deep, or perforator), and pathophysiology (reflux, obstruction, or both). This system was established in 1995 by an international Ad Hoc Committee of the American Venous Forum to encourage uniform reporting of venous disease and promote clinical study including natural history and treatment strategies.

Table 2.1. Basic CEAP classification of chronic venous disease | ||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

II. Anatomy.

Descriptions of venous anatomy have been historically limited by a lack of standardized nomenclature. The current consensus nomenclature should be utilized uniformly.

A.

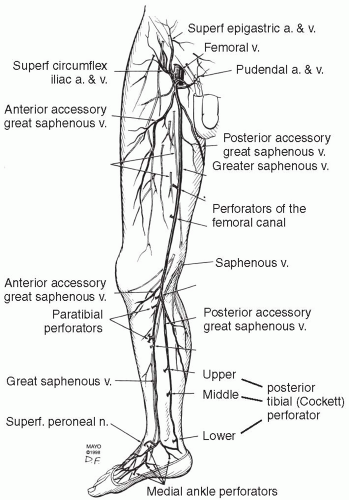

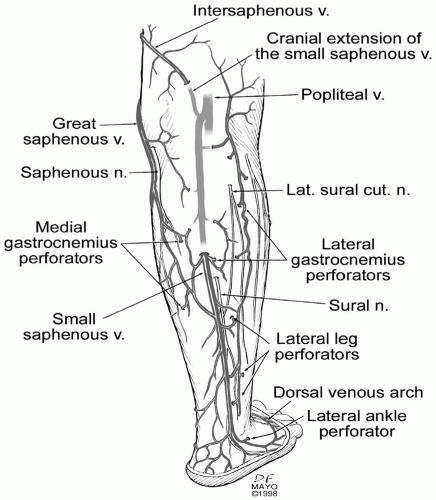

The superficial venous system (Fig. 2.1) of the lower extremity includes the great saphenous vein (GSV), small saphenous vein, and their tributaries. The GSV is occasionally duplicated in the thigh or calf. In the thigh, an anterior accessory GSV is the most constant branch. At the knee, the saphenous nerve becomes superficial and joins the great saphenous vein as it courses down the leg, an anatomic proximity that is relevant in instances where intervention on the great saphenous vein is considered. Below the knee, the posterior accessory saphenous vein drains into the great saphenous vein. Numerous medial perforating veins connect the deep calf veins with the great saphenous system and are called perforating veins. The small saphenous vein (formerly the lesser saphenous vein) ascends along a posterior course in the calf to join the popliteal vein in the popliteal fossa in the majority of limbs (Fig 2.2). As a normal variant, the small saphenous vein may continue cephalad to join the great saphenous or femoral vein.

B.

The deep veins of the lower extremity are the paired posterior tibial, peroneal, and anterior tibial veins in the calf, which ascend with their correspondingly named arteries. The popliteal vein becomes the femoral vein in the adductor canal. The profunda femoris vein drains the lateral thigh muscles, joining with the femoral vein to become the common femoral vein in the groin. The external iliac vein begins above the inguinal ligament, before its confluence with the internal iliac vein at the sacroiliac joint which then becomes the common iliac vein.

C.

Perforating veins connect the superficial with either the deep veins (direct perforators) or with venous sinuses in the calf (indirect perforators). Abundant perforating veins normally direct flow from the superficial toward the deep network via a system of venous valves. The more anatomically constant direct perforators are located in four general locations: medial calf (paratibial and posterior tibial perforators), lateral calf, thigh, and foot. Perforators have often been assigned eponyms, but in modern nomenclature are described according to their anatomic location.

D.

Venous sinuses comprise a thin-walled, valveless, large capacitance system located in the calf musculature. When the calf muscles contract, pressures in excess of 200 mm Hg are created, propelling venous blood toward the heart. A normally functioning calf-muscle pump displaces >60% of venous blood within that leg into the popliteal vein with a single contraction.