Chapter 1 Venous Anatomy

Historical Background

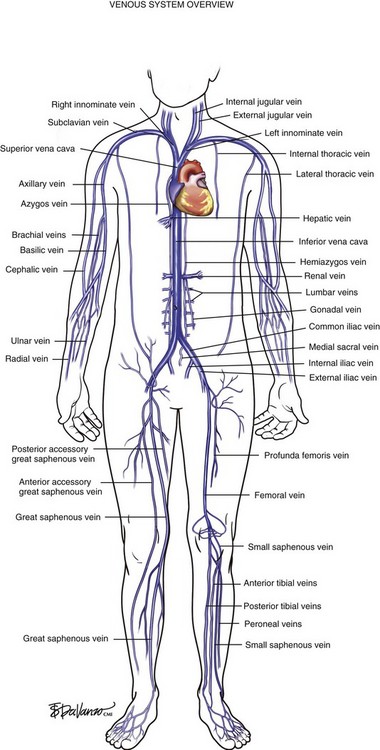

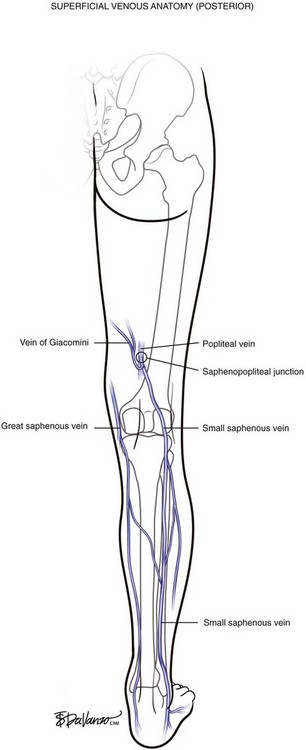

The venous system originates at the capillary level and progressively increases in size as the conduits move proximally toward the heart. The venules are the smallest structures, and the vena cava is the largest. It is critical that all endovascular venous surgeons understand the anatomic relationships between the thoracic, abdominal, and extremity venous systems; especially from the anatomic standpoint (Fig. 1-1). Veins of the lower extremities are the most germane to this book and are divided into three systems: deep, superficial, and perforating. Lower extremity veins are located in two compartments: deep and superficial. The deep compartment is bounded by the muscular fascia. The superficial compartment is bounded below by the muscular fascia and above by the dermis. The term perforating veins is reserved for veins that perforate the muscular fascia and connect superficial veins with deep veins. The term communicating veins is used to describe veins that connect with other veins of the same compartment.

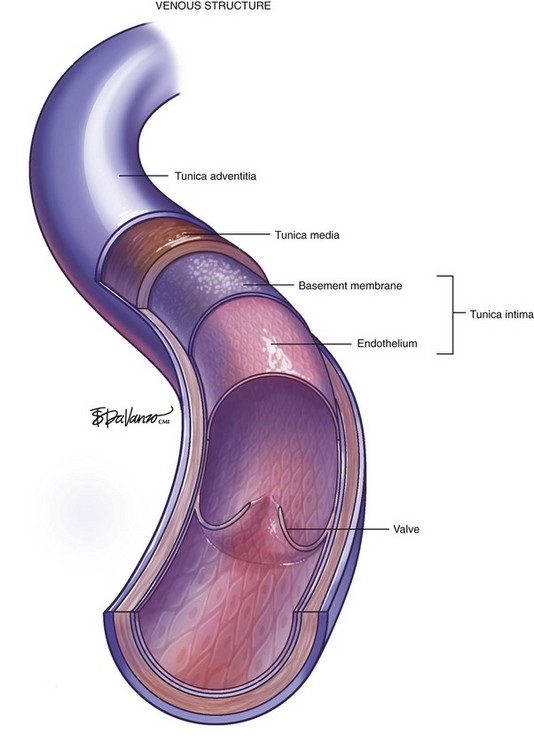

The vein wall is composed of three layers: intima, media, and adventitia. Notably, the muscular tunica media is much thinner than on the pressurized arterial side of the circulation. Venous valves are an extension of the intimal layer, have a bicuspid structure, and support unidirectional flow (Fig. 1-2).

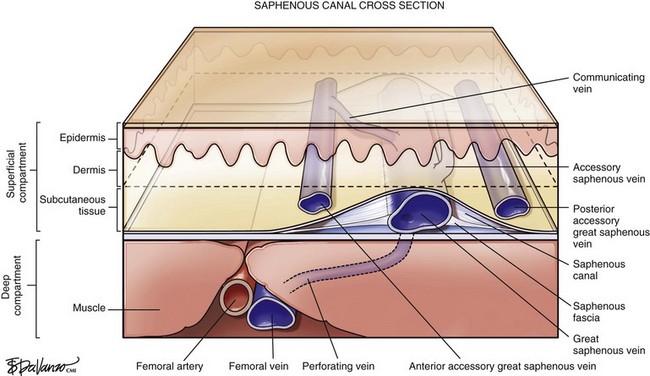

Surgeons interested in performing thermal or chemical ablation therapy of the great saphenous vein (GSV) and its related structures must have a good understanding of the saphenous canal. The importance of the saphenous canal in relation to B-mode ultrasound anatomy is discussed in more detail in Chapter 2. A cross section of the saphenous canal (Fig. 1-3) depicts many of the critical relationships referable to GSV treatment—the most important is how it courses atop the muscular fascia in a quasi-envelope called the saphenous fascia. The saphenous fascia is the portion of the membranous layer of the subcutaneous tissue that overlies the saphenous veins. Veins coursing parallel to the saphenous canal are termed accessory veins, whereas those coursing oblique to the canal are referred to as circumflex veins. Compressible structures superficial to the muscular fascia are potential targets for treatment; however, treating those structures deep to the muscular fascia may lead to a disastrous outcome. Noncompressible structures generally represent major arteries. Perforating veins must pierce the muscular fascia as they drain blood from the superficial to deep systems.

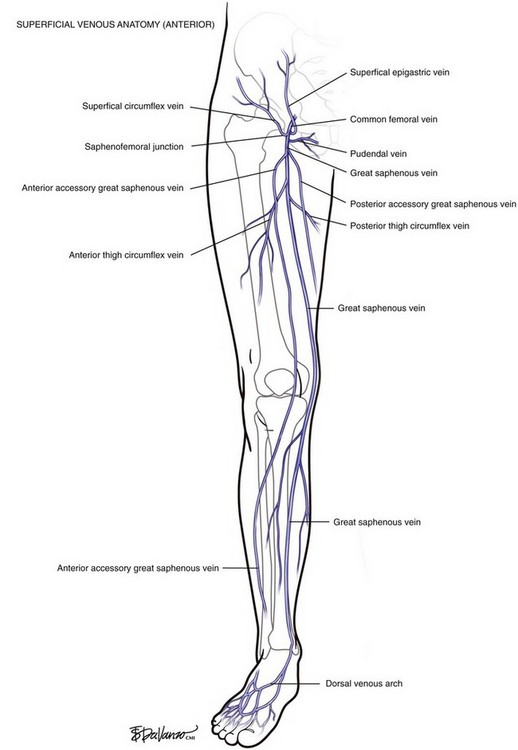

As diagnostic and therapeutic options for venous disorders expanded, the nomenclature proposed in 2002 by the International Interdisciplinary Committee1 required revision. The nomenclature was extended and further refined,2 taking into account recent improvements in ultrasound and clinical surgical anatomy. The term great saphenous vein should be used instead of terms such as long saphenous vein, greater saphenous vein, or internal saphenous vein. The LSV abbreviation, used to describe both the long saphenous vein and lesser saphenous vein, was clearly problematic. For this reason these terms have been eliminated. Similarly, the term small saphenous vein, abbreviated as SSV, should be used instead of the terms short, external, or lesser saphenous vein.

The GSV originates at the medial foot and receives deep pedal tributaries as it courses to the medial malleolus. From the medial ankle, the GSV ascends anteromedially within the calf and continues a medial course to the knee and into the thigh. The termination point of the GSV into the common femoral vein is a confluence called the saphenofemoral junction (SFJ) (Fig. 1-4).

In variant drainage, a standard SPJ may or may not be present. The SSV is truly duplicated in 4% of cases; most often this is segmental and primarily involves the midportion of the vein (Fig. 1-5).

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree