Chapter 78

Vasculitis and Other Uncommon Arteriopathies

Kenneth J. Warrington, Leslie T. Cooper Jr.,

Arterial vascular disease is usually associated with advanced age and traditional risk factors related to atherosclerosis. However, vasculitis and other uncommon, noninflammatory arteriopathies can present with both ischemic symptoms from occlusive disease and degenerative lesions such as aneurysms and require specific diagnostic evaluation and treatment. The disorders reviewed in this chapter can be distinguished from atherosclerotic disease by several clinical features, including young age at presentation and paucity of traditional risk factors. In some cases, another clue to vasculitis is a systemic constitutional syndrome of fevers, chills, night sweats, or unexplained weight loss. Evidence of a multisystem disorder on examination or laboratory testing, with elevated inflammatory biomarkers, is also suggestive. A temporal association with a new drug may suggest drug-related vasospasm or vasculitis. A positive family history is a useful clue to an inherited vasculopathy such as pseudoxanthoma elasticum or neurofibromatosis.

Vasculitis

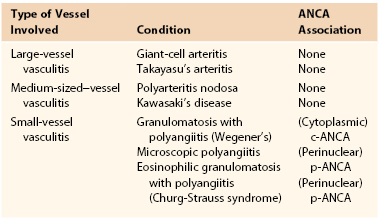

Vessels of any size or location can be affected by vasculitis. Vasculitis implies inflammation of vessel walls, resulting in vascular damage and a wide variety of clinical signs and symptoms. Vasculitis can be classified based on the predominant type of vessel involved (referred to as large-, medium-, or small-vessel vasculitis).1 The major forms of small-vessel vasculitis are associated with the presence of antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA) (Table 78-1).

Large-Vessel Vasculitis

The large-vessel vasculitides include Takayasu’s arteritis and giant-cell arteritis (GCA). Both conditions can affect the aorta and its major branches. However, GCA, also known as temporal arteritis, primarily involves the extracranial branches of the carotid artery. GCA is the most common form of systemic vasculitis in adults and usually affects older adults.2 Conversely, Takayasu’s arteritis occurs in younger individuals and has distinct clinical features. Takayasu’s arteritis is reviewed in detail in Chapter 80.

Giant Cell Arteritis

Epidemiology.

GCA occurs predominantly in individuals older than 50 years, and its incidence is highest in individuals between 70 and 80 years of age. Women are affected two to four times as often as men. The incidence of GCA varies by race and geographic location: GCA is most common among people of Northern European descent and is rare in African Americans and Asians.3–7 In Olmsted County, Minnesota, the incidence of GCA has remained stable over the last 20 years with an average annual incidence of about 19 cases per 100,000 persons aged 50 years and older.3 Similar incidence rates have been reported in Northern European populations.6 In Southern Europe, GCA is less common; the average annual incidence for the population aged 50 and older is about 7 to 10 per 100,000.8,9

Pathogenesis.

The exact cause of GCA remains unknown. The condition is probably triggered by an environmental cause in a genetically predisposed older adult. Genetic polymorphisms of the human leukocyte antigen (HLA) class II region, specifically the HLA-DRB1*04 and DRB1*01 alleles, are associated with susceptibility to GCA.10 Polymorphisms in genes encoding cytokines and other immunoregulatory proteins have also been associated with an increased risk of developing GCA.11 Circumstantial evidence suggests that GCA may be triggered by infectious agents such as Mycoplasma pneumoniae, parvovirus B19, parainfluenza virus, and Chlamydia pneumonia. However, conclusive evidence is lacking.12,13 Histopathologic examination of temporal arteries involved by GCA reveals inflammatory infiltrates composed of T cells and macrophages. Multinucleated giant cells, typically adjacent to a fragmented internal elastic lamina, are present in about 50% of cases. The inflammatory process is thought to arise in the adventitial layer of the arterial wall. Activated, mature dendritic cells attract CD4 T cells to the artery through the vasa vasorum, and upon activation, T cells undergo clonal expansion. T cells release cytokines including interferon-gamma (INF-γ), which stimulate macrophages and induce formation of multinucleated giant cells. Interleukin-17–producing T cells have also been implicated in disease pathogenesis. Macrophages amplify inflammation via secretion of cytokines and induce tissue damage by releasing matrix metalloproteinases and reactive oxygen species. In response to immunologic injury, the artery releases growth and angiogenic factors (platelet-derived growth factor and vascular endothelial growth factor), which induce proliferation of myofibroblasts, new vessel formation, and marked thickening of the arterial intima. This process of intimal expansion and hyperplasia leads to narrowing and possibly, occlusion of the vessel lumen, which results in symptoms of ischemia such as jaw claudication, visual loss or stroke.14–17

Clinical Presentation.

GCA should be suspected in individuals older than 50 years who present with new-onset headache in the presence of systemic inflammation. Headache may be accompanied by scalp tenderness and thickening or nodularity of the temporal arteries. Although present in only about a third of patients, jaw claudication is a characteristic symptom of GCA. Patients can also present with predominantly constitutional symptoms such as fatigue, weight loss, and fever. Ocular symptoms such as decreased vision, diplopia, and amaurosis fugax are common, and up to one fifth of patients develop permanent visual loss. About one third of patients with GCA experience symptoms of polymyalgia rheumatica, including pain and stiffness in the neck and proximal extremities. Neurologic manifestations are less common and may include stroke, transient ischemic attack or neuropathy. Patients with large vessel stenoses may present with claudication of the upper extremities or asymmetric blood pressures.2,18

Diagnostic Evaluation.

Physical examination of patients with possible GCA should include careful assessment of the temporal arteries for thickening, tenderness, or nodularity. A clinically abnormal temporal artery is highly predictive of positive findings on temporal artery biopsy.19 Bilateral brachial artery blood pressure measurements and a complete vascular examination including assessment of peripheral pulses and auscultation for bruits should be documented. The American College of Rheumatology’s 1990 criteria for the classification of GCA are listed in Table 78-2. For the diagnosis of GCA, at least three of the five criteria must be present. The presence of any three or more criteria yields a sensitivity of 93.5% and a specificity of 91.2% for distinguishing GCA from other forms of vasculitis.20

Table 78-2

The American College of Rheumatology 1990 Criteria for the Classification of Giant Cell Arteritis*

| Criterion | Definition |

| 1. Age at disease onset ≥50 years | Development of symptoms or findings beginning at age 50 or older |

| 2. New headache | New onset of or new type of localized pain in the head |

| 3. Temporal artery abnormality | Temporal artery tenderness to palpation or decreased pulsation, unrelated to arteriosclerosis of cervical arteries |

| 4. Elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate | Erythrocyte sedimentation rate ≥50 mm/hour by the Westergren method |

| 5. Abnormal artery biopsy | Biopsy specimen with artery showing vasculitis characterized by a predominance of mononuclear cell infiltration or granulomatous inflammation, usually with multinucleated giant cells |

* For the diagnosis of GCA, at least three of the five listed criteria must be present.

Hunder GG, et al: The American College of Rheumatology 1990 criteria for the classification of giant cell arteritis. Arthritis Rheum 33:1122-1128, 1990.

Inflammatory markers, including the erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and C-reactive protein (CRP) are often markedly elevated in GCA, although a minority of patients may have a normal ESR. Most patients have a normochromic normocytic anemia and elevated platelet count. Abnormal liver function tests, including elevation of alkaline phosphatase, are present in a subset of cases. The “gold standard” diagnostic test for GCA is histopathologic examination of a temporal artery biopsy. An adequate length of temporal artery (2 to 3 cm) should be obtained at biopsy, and bilateral biopsies are preferable (in particular, if the first side is negative). In some patients with GCA, temporal artery biopsy may be normal, particularly in the subset of patients with large artery disease.21 Large vessel involvement may be diagnosed by conventional angiography, magnetic resonance angiography, or computed tomography angiography scan. Other imaging modalities such as positron emission tomography are being evaluated as diagnostic tools for large-vessel GCA.22

Extracranial GCA.

Clinically significant stenoses of branches of the aortic arch, especially the subclavian and axillary arteries, occur in 10% to 15% of patients with GCA (Fig. 78-1).23,24 Schmidt et al screened 176 patients with GCA for subclavian involvement using ultrasound.25 The authors found changes of vasculitis with homogeneous wall swelling of the axillary, subclavian, and/or proximal brachial arteries in about 30% of patients. Most of these patients had bilateral disease. This study suggests that involvement of the upper extremity arteries may be more common than was previously recognized. GCA can involve the aorta and the incidence of aortic aneurysm after a diagnosis of GCA is about 10%.24 Indeed, patients with GCA have a 17-fold increased risk of thoracic aneurysms and a 2.4-fold increased risk of abdominal aneurysms compared with individuals of the same age and gender.26 Thoracic aortic aneurysms may result in dissection and markedly increased mortality.27 Patients with concomitant hyperlipidemia and coronary artery disease appear to be at greatest risk of aortic aneurysm and/or dissection.23 Given the increased risk of aortic aneurysmal disease in patients with GCA, long-term monitoring with periodic imaging of the aorta is advisable.24 In a subset of cases examined histologically, active giant cell aortitis was evident at the time of surgical repair or autopsy.26

Medical Treatment.

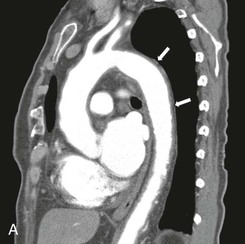

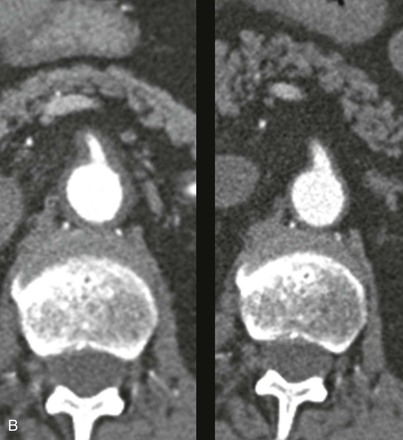

The goals of treatment are to improve patients’ symptoms and prevent sequelae from ischemic events. Treatment for possible GCA can be initiated while awaiting temporal artery biopsy because histopathologic evidence of arteritis, if present, persists for several weeks.28,29 Although it has not been evaluated in randomized controlled clinical trials, corticosteroid therapy is the standard of care for GCA. Guidelines recommend that the initial standard oral dose of prednisone should be 40 to 60 mg daily.30,31 Lower-dose prednisone is of uncertain efficacy and alternate-day corticosteroid therapy is not recommended.32 Intravenous methylprednisolone (1000 mg daily for 3 days) may be considered for patients presenting with visual loss.33 The initial prednisone dose should be maintained for 4 weeks, and it is then tapered by about 10% every 2 to 4 weeks depending on clinical evaluation and levels of inflammatory markers (Fig. 78-2A, B). Up to 50% of patients with GCA experience unpredictable disease relapses requiring increases in the steroid dose.12 If there are no contraindications to antiplatelet therapy, low-dose aspirin should be started because it may reduce the risk of ischemic events such as visual loss.30,34,35 Measures to prevent or treat steroid-related side effects are an essential aspect of managing GCA. These may include screening for and treating steroid-induced diabetes, hypertension, and osteoporosis. Prophylaxis for pneumocystis pneumonia should be considered for patients on high-dose steroids.30 Steroid-sparing immunosuppressive medications are not very effective for GCA. However, in patients with steroid-related toxicity and frequent disease relapses, the addition of methotrexate may allow reduction in the prednisone dosage.36 Inhibitors of tumor necrosis factor are generally not effective for GCA.37 An inhibitor of interleukin-6 (tocilizumab) has shown promise in early observational studies.38

Figure 78-2 CT angiogram of a patient with GCA and involvement of the aorta. A, This sagittal image demonstrates thickened arterial walls, most prominent in the great vessels, and throughout the entire descending thoracic aorta. B, Arterial wall thickening extended into the upper abdominal aorta and superior mesenteric artery (SMA), which was stenosed (left panel). Reimaging after 6 months of treatment with corticosteroids revealed marked improvement in the diffuse arterial wall thickening and SMA stenosis (right panel).

Revascularization of arteries to the extremities is rarely required in GCA because of the collateral circulation that develops in this disease. Successful balloon angioplasty of upper-extremity arteries, in combination with immunosuppressive treatment, has been reported in small case series. However, there is tendency for restenoses to develop in these patients.39 Zehr et al reported their experience with surgical treatment of ascending aortic aneurysms in patients with GCA. Among these patients, 4-year survival was 74%, and surgical results were similar to those of surgery for aneurysms caused by other etiologies.40

Idiopathic Aortitis

Idiopathic aortitis is characterized by giant cell or lymphoplasmacytic inflammation of the aorta. This condition typically affects the ascending aorta and accounts for 2% to 4% of aortic aneurysms. Although aortitis is known to occur in a variety of rheumatologic conditions, idiopathic aortitis is usually diagnosed incidentally following ascending aneurysm repair in individuals without a history of rheumatic disease.41,42 Idiopathic aortitis appears to be more common among elderly females. Miller et al recorded 45 cases of incidental aortitis in a retrospective review of 514 ascending aortic specimens (frequency of 8.8%).43 A subset of these patients may develop additional aortic aneurysms, and the role of immunosuppression in idiopathic aortitis is still unclear.

Medium-Sized–Vessel Vasculitis

Polyarteritis Nodosa

Polyarteritis nodosa (PAN) is a form of necrotizing vasculitis that predominantly involves medium-sized arteries with the vasculature of the kidneys, skin, muscles, nerves, and gastrointestinal tract being most commonly affected. PAN can be broadly divided into primary (idiopathic) and secondary (related to hepatitis B virus [HBV] infection) forms.44 The 1990 American College of Rheumatology criteria for the diagnosis of PAN are listed in Table 78-3. The presence of 3 or more of these 10 criteria distinguishes PAN from other forms of vasculitis with a sensitivity of 82.2% and specificity of 86.6%.45 Although older studies did not distinguish PAN from microscopic polyangiitis (MPA), major differences exist between the two, and these are now considered separate entities (see later under Small-Vessel Vasculitis).

Table 78-3

The American College of Rheumatology 1990 Criteria for the Classification of Polyarteritis Nodosa*

| Criterion | Definition |

| 1. Weight loss ≧4 kg | Loss of 4 kg or more of body weight since illness began, not due to dieting or other factors |

| 2. Livedo reticularis | Mottled reticular pattern over the skin of portions of the extremities or torso |

| 3. Testicular pain or tenderness | Pain or tenderness of the testicles not due to infection, trauma, or other causes |

| 4. Myalgias, weakness, or leg tenderness | Diffuse myalgias (excluding shoulder and hip girdle) or weakness of muscles or tenderness of leg muscles |

| 5. Mononeuropathy or polyneuropathy | Development of mononeuropathy, multiple mononeuropathies, or polyneuropathy |

| 6. Diastolic BP >90 mm Hg | Development of hypertension with the diastolic BP higher than 90 mm Hg |

| 7. Elevated BUN or creatinine | Elevation of BUN >40 mg/dL or creatinine >1.5 mg/dL, not due to dehydration or obstruction |

| 8. Hepatitis B virus | Presence of hepatitis B surface antigen or antibody in serum |

| 9. Arteriographic abnormality | Arteriogram showing aneurysms or occlusions of the visceral arteries, not due to arteriosclerosis, fibromuscular dysplasia, or other noninflammatory causes |

| 10. Biopsy of small or medium-sized artery containing PMN | Histologic changes showing the presence of granulocytes or granulocytes and mononuclear leukocytes in the artery wall |

* For classification purposes, a patient shall be said to have polyarteritis nodosa if at least 3 of the 10 listed criteria are present.

BP, Blood pressure; BUN, blood urea nitrogen; PMN, polymorphonuclear neutrophils.

Lightfoot RW, Jr, et al: The American College of Rheumatology 1990 criteria for the classification of polyarteritis nodosa. Arthritis Rheum 33:1088-1093, 1990.

Epidemiology.

PAN is a rare disease with an annual incidence in Europe that ranges from 4.4 to 9.7 per million population.46 It can affect individuals of any age and is more common in men, occurring mainly between the age of 40 and 60 years.47,48 The incidence of PAN appears to be declining, likely related to a decrease in the prevalence of HBV infection.48

Pathogenesis.

In most cases of PAN, the cause is unknown. However, in about a third of cases, PAN is the consequence of HBV infection.49 In a recent series of HBV-related PAN, the mean time between the diagnoses of hepatitis and PAN was approximately 7 months.48 Other viruses, including human immunodeficiency virus, have been implicated in disease pathogenesis.50 Some cases of PAN may occur as a paraneoplastic process related to hematologic malignancies, particularly hairy-cell leukemia.51 The histologic lesion seen in PAN is a focal, segmental necrotizing vasculitis that predominantly affects medium-sized arteries. The arterial wall inflammation is characterized by fibrinoid necrosis of the media and a cellular infiltrate primarily composed of neutrophils and lymphocytes. Active necrotizing lesions are frequently seen with concurrent healed or fibrotic lesions. Localized thromboses can occur at the site of inflammation, and arterial aneurysms may form as a result of the weakening of the vessel wall by the necrotizing process, ultimately leading to end organ injury from ischemia, infarct, and hemorrhage.44,52

Little is known about the underlying pathogenetic mechanisms in PAN. In patients with HBV-related PAN, deposition of viral antigen-antibody complexes can lead to activation of the complement cascade, which in turn, results in neutrophil attraction and activation.53 Although antiendothelial cell antibodies have been detected in patients with PAN, it is unclear whether they are of pathogenic significance.54 T cells, particularly the CD8+ subset, have been identified in inflammatory infiltrates and may be involved in disease pathogenesis.55

Clinical Presentation.

Patients with PAN typically present with constitutional symptoms such as fever and weight loss in the setting of multiorgan dysfunction. Neurologic involvement occurs in up to 70% of patients with PAN and usually manifests as a mononeuritis multiplex or sensorimotor peripheral neuropathy.56 Abdominal pain is a common presenting feature suggesting gastrointestinal (GI) involvement. GI manifestations occur in 40% to 60% of patients with PAN and may include mesenteric ischemia, GI hemorrhage, bowel perforation, and pancreatitis.57,58 Severe GI involvement is a major cause of death in patients with PAN.59 Renal involvement with glomerular ischemia and infarction frequently leads to variable degrees of renal insufficiency and hypertension. Microaneurysms of renal artery branches can occasionally rupture and cause renal hematomas.60 Myalgias due to skeletal muscle involvement and large-joint arthralgias are common.61 Testicular pain due to testicular artery ischemia is a characteristic disease manifestation, but this only occurs in about 20% of patients. Skin manifestations of PAN may include livedo reticularis, tender subcutaneous nodules, and skin ulcerations. Peripheral arterial occlusions can result in ischemia and gangrene of toes or fingers and may mimic atheroembolic disease. Central nervous system and cardiac involvement (cardiomyopathy, coronary vasculitis) are uncommon but indicate a poor prognosis if present.59,62,63 The clinical features of HBV-related PAN are overall similar to those of idiopathic PAN. Localized PAN involving a single organ (e.g., appendix, gallbladder) is occasionally identified on histopathologic examination of surgical specimens. This form of PAN is frequently cured by surgical resection alone and carries a good prognosis.44 PAN typically does not affect the lungs, a feature that is often helpful in distinguishing this condition from the ANCA-associated vasculitides, which often involve the pulmonary capillaries.

Diagnostic Evaluation.

In addition to the clinical evaluation, laboratory studies are often helpful in reaching a diagnosis and determining disease severity. Markers of systemic inflammation, such as the ESR and CRP, are elevated in the majority of patients with PAN; anemia and leukocytosis are also common. Blood work should include serum creatinine, muscle enzyme concentrations, liver function tests, and hepatitis serologies. However, there is no diagnostic laboratory test for PAN, and ANCA tests are typically negative. Indeed, some investigators have proposed that ANCA positivity should be considered a criterion for excluding the diagnosis of PAN.44 Urinalysis may reveal proteinuria and perhaps modest hematuria, but active urinary sediment is usually absent. Computed tomography of the abdomen can be useful in detecting organ infarcts and/or bowel-wall thickening. Characteristic findings on conventional angiography such as multiple microaneurysms of the celiac, mesenteric, and renal artery branches are often diagnostic of PAN.64,65 Depending on the pattern of clinical involvement, muscle, nerve, or deep-skin biopsies for histopathologic confirmation of vasculitis may be required in some patients. Surgical specimens from patients with visceral involvement (e.g., small intestine) can also provide the diagnosis.

Medical Treatment.

Although untreated PAN is associated with a poor prognosis, excellent 5-year survival rates of over 80% can be achieved with appropriate immunosuppressive therapy.66 Treatment of PAN should be tailored to disease severity. Approximately 50% of PAN cases can be cured with glucocorticoid treatment alone (prednisone 1 mg/kg per day for 4 weeks with subsequent taper), usually in courses lasting a total of 9 to 12 months.67 This regimen is appropriate for patients with mild disease and avoids the risks associated with more intense immunosuppressive therapy. Patients with PAN who have poor prognostic indicators (e.g., renal insufficiency or gastrointestinal, cardiac, or neurologic involvement) require glucocorticoids combined with cyclophosphamide to induce disease remission.68,69 Cyclophosphamide is usually given orally at a dose of 1.5 to 2 mg/kg/day or by monthly intravenous infusion (600 to 750 mg/m2).70 The dose should be carefully adjusted, depending on response to therapy, renal function, and hematologic parameters. Treatment with cyclophosphamide should be continued for at least 6 months, after which it can be replaced with less toxic agents such as methotrexate or azathioprine, for a total treatment duration of 12 to 18 months. PAN has low relapse rates and therefore typically does not require long-term maintenance therapy. Strategies to limit treatment-related comorbidities are essential and should include measures to prevent bone loss and opportunistic infections, such as Pneumocystis pneumonia. Hypertension is common in patients with PAN, and angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors are often effective in this setting. However, ACE inhibitors may worsen renal function, and creatinine levels should be monitored closely.

In HBV-related PAN, a combination of antiviral therapy (such as lamivudine or entecavir) and limited immunosuppressive therapy is typically employed.71 A brief course of glucocorticoids (2 weeks) is given initially to contain the inflammatory component of the vasculitis, and an antiviral agent is started concurrently. Prolonged glucocorticoid therapy and cyclophosphamide should be avoided to allow immunologic clearance of HBV-infected hepatocytes. Plasma exchange for removal of immune complexes can be considered for patients with HBV-related PAN and severe manifestations of vasculitis. In a French series of patients with HBV-related PAN, treatment with 2 weeks of steroids followed by an antiviral agent combined with plasma exchange resulted in a remission rate of 81% and 5-year survival of 73%.48

Kawasaki Disease

Kawasaki disease (KD) is an acute vasculitis involving small and medium-sized arteries, particularly the coronary arteries. Most patients are younger than 5 years old, and boys are affected 1.5 times more often than girls. The incidence of KD in the United States ranges from 9.1 to 16.9 cases per 100,000 children younger than 5 years old. Coronary arterial dilatation or aneurysmal formation can occur in up to 25% of untreated patients, and the main cause of death in KD is myocardial infarction. Other cardiac manifestations may include valvular heart disease, myocarditis, and pericarditis. Less commonly, systemic artery involvement in KD may result in aneurysms of the iliac, axillary, or renal arteries. Treatment with aspirin and intravenous immune globulin is effective and reduces the incidence of coronary artery aneurysms.72–74

Small-Vessel Vasculitis

Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis, Microscopic Polyangiitis, and Eosinophilic Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis

Granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA; also known as Wegener’s granulomatosis), microscopic polyangiitis (MPA), and eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (EGPA; also called Churg-Strauss syndrome) are primary systemic vasculitides that involve mainly small vessels. Patients with these three conditions often have circulating ANCA; therefore GPA, MPA, and EGPA are also collectively known as the ANCA-associated vasculitides (AAV).75 A revised nomenclature of vasculitides was published recently.76

Epidemiology.

The overall incidence of AAV is approximately 10 to 20 per million population per year. GPA is the most common form of AAV (incidence of 8-10/million, followed by MPA (2-6/million) and EGPA (1-4/million). These conditions occur more frequently in older adults with a peak onset in the 65- to 70-year-old age group and affect men and women equally. AAV is more prevalent in whites compared with other populations.46,75,77

Pathogenesis.

As with other forms of vasculitis, the etiology of AAV remains unknown. Genetic and environmental factors, including infections, are thought to play a role in disease pathogenesis. ANCA are present in most patients with small-vessel vasculitis and are specific for antigens in neutrophil granules and monocyte lysosomes. These antibodies can be detected by immunofluorescent techniques, which produce two major staining patterns: cytoplasmic ANCA (c-ANCA) and perinuclear ANCA (p-ANCA). About 90% of patients with GPA are c-ANCA positive, and the target antigen recognized by ANCA is typically proteinase-3 (PR-3). Most patients with MPA and EGPA are p-ANCA positive, owing to reactivity with myeloperoxidase (MPO). There is a growing body of literature based on clinical, in vitro, and experimental animal observations suggesting that ANCA have an important pathogenic role in the development of AAV.75,78

Histologically, GPA is characterized by a necrotizing granulomatous vasculitis. Necrotizing granulomatous inflammation is also seen in EGPA. However, asthma and eosinophilia are prominent features in EGPA that are not seen in GPA. MPA is characterized by necrotizing small-vessel vasculitis without pathologic evidence of granulomatous inflammation, which helps to distinguish this condition from GPA.75,76

Clinical Presentation.

Most patients with AAV present with constitutional symptoms, including fever and weight loss, in addition to symptoms related to variable involvement of the internal organs. GPA classically involves the kidneys and the upper and lower respiratory tract. Clinical manifestations may include symptoms of sinusitis or otitis, in addition to oral and nasal ulcers. Necrosis of the nasal septum with perforation may occur. Tracheal inflammation can present with stridor and respiratory distress. Pulmonary involvement may present as pulmonary nodules/masses, whereas alveolar capillaritis causes pulmonary hemorrhage and lung infiltrates. Massive pulmonary hemorrhage can be a life-threatening manifestation of AAV. Approximately 80% of patients with GPA develop glomerulonephritis and rapidly progressive renal failure. Other manifestations of the disease may include ocular inflammation, skin vasculitis, peripheral neuropathy, arthritis, and gastrointestinal vasculitis.79

Renal involvement with rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis occurs in almost all cases of MPA. Alveolar hemorrhage is a common pulmonary manifestation. Other clinical features that can be seen in MPA include cutaneous vasculitis, peripheral neuropathy, and vasculitis of the gastrointestinal tract, among others.80 About 75% of patients with MPA are p-ANCA (MPO) positive.

EGPA typically has three main features: allergic rhinitis and asthma; eosinophilic infiltrative disease, such as eosinophilic pneumonia; and systemic small-vessel vasculitis. EGPA involves the lungs, peripheral nerves, skin, and, less frequently, the heart and gastrointestinal tract. Compared with GPA and MPA, EGPA typically causes less renal disease, but cardiac involvement is a frequent cause of morbidity and mortality. All patients with EGPA have eosinophilia (>10% eosinophils in the blood) and about 40% are p-ANCA (MPO) positive.81,82

Diagnostic Evaluation.

The diagnosis of AAV requires an integration of clinical, laboratory, and histopathologic findings. Laboratory assessment for inflammatory markers (ESR, CRP), liver and renal function, ANCA, antinuclear antibodies, complement, cryoglobulins, hepatitis serologies, rheumatoid factor, and urinalysis should be obtained. ANCA testing is helpful in reaching a diagnosis of AAV, but it should be recognized that a subset of patients with small-vessel vasculitis is ANCA negative. In addition, serial measurements of ANCA over time do not correlate well with disease activity or risk of relapse and therefore cannot be used to guide immunosuppressive therapy.83

Patients should undergo chest imaging for assessment of pulmonary involvement and, when indicated, nerve-conduction studies to evaluate for peripheral neuropathy. Pathologic examination of involved tissue, such as skin, muscle, nerve, lung, or kidney, is often necessary to document small-vessel vasculitis. A prompt diagnosis of AAV is essential, because life-threatening injury to internal organs progresses rapidly and can be attenuated with appropriate therapy.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree