Vascular Disorders

Vascular disorders can affect the arteries, the veins, or both types of vessels. Arterial disorders include aneurysms, which result from a weakening of the arterial wall; arterial occlusive disease, which commonly results from atherosclerotic narrowing of the artery’s lumen; and Raynaud’s disease, which may be linked to immunologic dysfunction. Thrombophlebitis, a venous disorder, results from inflammation or occlusion of the affected vessel.

ABDOMINAL AORTIC ANEURYSM

Abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA), an abnormal dilation in the arterial wall, generally occurs in the aorta between the renal arteries and iliac branches. Rupture, in which the aneurysm breaks open, resulting in profuse bleeding, is a common complication that occurs in larger aneurysm. Dissection occurs when the artery’s lining tears and blood leaks into the walls.

AAA is four times more common in men than in women and is most prevalent in whites ages 40 to 70. Less than half of people with a ruptured AAA survive.

Pathophysiology

Aortic aneurysms develop slowly. First, a focal weakness in the muscular layer of the aorta (tunica media), caused by degenerative changes, allows the inner layer (tunica intima) and outer layer (tunica adventitia) to stretch outward. Blood pressure within the aorta progressively weakens the vessel walls and enlarges the aneurysm.

Nearly all AAAs are fusiform, which causes the arterial walls to balloon on all sides. The resulting sac fills with necrotic debris and thrombi.

About 95% of abdominal aneurysms result from arteriosclerosis or atherosclerosis; the rest, from cystic medial necrosis, trauma, hypertension, blunt abdominal injury, syphilis, and other infections.

Complications

Rupture

Obstruction of blood flow to other organs

Embolization to a peripheral artery

Diminished blood supply to vital organs resulting in organ failure (with rupture)

Assessment findings

Most patients with abdominal aneurysms are asymptomatic until the aneurysm enlarges and compresses surrounding tissue.

A large aneurysm may produce signs and symptoms that mimic renal calculi, lumbar disk disease, and duodenal compression.

The patient may complain of gnawing, generalized, steady abdominal pain or low back pain that’s unaffected by movement. He may have a sensation of gastric or abdominal fullness caused by pressure on the GI structures.

RED FLAG

RED FLAGSudden onset of severe abdominal pain or lumbar pain that radiates to the flank and groin from pressure on lumbar nerves may signify enlargement and imminent rupture. If the aneurysm ruptures into the peritoneal cavity, severe and persistent abdominal and back pain, mimicking renal or ureteral colic, occurs. If it ruptures into the duodenum, GI bleeding occurs with massive hematemesis and melena.

The patient may have a syncopal episode when an aneurysm ruptures, causing hypovolemia and a subsequent drop in blood pressure. Once a clot forms and the bleeding stops, he may again be asymptomatic or have abdominal pain because of bleeding into the peritoneum.

Inspection of the patient with an intact abdominal aneurysm usually reveals no significant findings. However, if the patient isn’t obese, you may notice a pulsating mass in the periumbilical area.

If the aneurysm has ruptured, you may notice signs of hypovolemic shock, such as skin mottling, decreased level of consciousness (LOC), diaphoresis, and oliguria.

The abdomen may appear distended, and an ecchymosis or hematoma may be present in the abdominal, flank, or groin area.

Paraplegia may occur if the aneurysm rupture reduces blood flow to the spine.

Auscultation of the abdomen may reveal a systolic bruit over the aorta caused by turbulent blood flow in the widened arterial segment. Hypotension occurs with aneurysm rupture.

Palpation of the abdomen may disclose some tenderness over the affected area. A pulsatile mass may be felt; however, avoid deep palpation to locate the mass because this may cause the aneurysm to rupture.

Palpation of the peripheral pulses may reveal absent pulses distal to a ruptured aneurysm.

Diagnostic test results

Because an abdominal aneurysm seldom produces symptoms, it’s typically detected accidentally on an X-ray or during a routine physical examination.

Several tests can confirm suspected abdominal aneurysm:

Abdominal ultrasonography or echocardiography can help determine the size, shape, and location of the aneurysm.

Anteroposterior and lateral X-rays of the abdomen can be used to detect aortic calcification, which outlines the mass, at least 75% of the time.

A computed tomography scan can be used to visualize the aneurysm’s effect on nearby organs, particularly the position of the renal arteries in relation to the aneurysm.

Aortography shows the condition of vessels proximal and distal to the aneurysm and the extent of the aneurysm, but the diameter of the aneurysm may be underestimated because aortography shows only the flow channel and not the surrounding clot.

Magnetic resonance imagining can be used as an alternative to aortography.

Treatment

Usually, abdominal aneurysm requires resection of the aneurysm and Dacron graft replacement of the aortic section. If the aneurysm is small and produces no symptoms, surgery may be delayed; however, small aneurysms can rupture. A beta-adrenergic receptor blocker may be given to decrease the rate of growth of the aneurysm. Regular physical examination and ultrasound checks help monitor progression of the aneurysm. Large aneurysms or those that produce symptoms risk rupture and require immediate repair. In asymptomatic patients, surgery is advised when the aneurysm is 5 to 6 cm in diameter. In symptomatic patients, repair is indicated regardless of size. In patients with

poor perfusion distal to the aneurysm, external grafting may be done. (See Repairing abdominal aortic aneurysms with endovascular grafting.)

poor perfusion distal to the aneurysm, external grafting may be done. (See Repairing abdominal aortic aneurysms with endovascular grafting.)

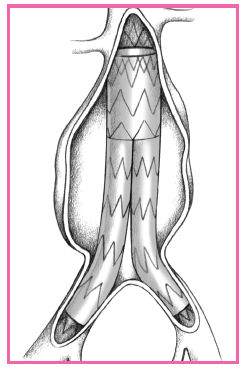

REPAIRING ABDOMINAL AORTIC ANEURYSMS WITH ENDOVASCULAR GRAFTING

Endovascular grafting is a minimally invasive procedure used to repair abdominal aortic aneurysms. Such grafting reinforces the walls of the aorta to prevent rupture and prevents expansion of the aneurysm.

The procedure is performed with fluoroscopic guidance, with a delivery catheter with an attached compressed graft inserted through a small incision into the femoral or iliac artery over a guide wire. The delivery catheter is advanced into the aorta, where it’s positioned across the aneurysm. A balloon on the catheter expands the graft and affixes it to the vessel wall. The procedure generally takes 2 to 3 hours to perform. Patients are instructed to walk the first day after surgery and are discharged from the facility in 1 to 3 days.

|

For patients with acute dissection, emergency treatment before surgery includes resuscitation with fluid and blood replacement, I.V. propranolol (Inderal) to reduce myocardial contractility, I.V. nitroprusside (Nitropress) to reduce and maintain blood pressure to 100 to 120 mm Hg systolic, and an analgesic to relieve pain. An arterial line and indwelling urinary catheter are inserted to monitor the patient’s condition.

Nursing interventions

IN A NONACUTE SITUATION

Allow the patient to express his fears and concerns. Help him identify effective coping strategies as he attempts to deal with his diagnosis.

Offer the patient and his family psychological support. Answer all questions honestly and provide reassurance.

Before elective surgery, weigh the patient, insert an indwelling urinary catheter and an I.V. line, and assist with insertion of the arterial line and pulmonary artery catheter to monitor hemodynamic balance.

Give a prophylactic antibiotic as ordered.

IN AN ACUTE SITUATION

Monitor the patient’s vital signs on his admission to the intensive care unit (ICU).

Insert an I.V. line with at least a 18G needle to facilitate blood replacement.

Obtain blood samples for kidney function tests (such as blood urea nitrogen, creatinine, and electrolyte levels), a complete blood count with differential, blood typing and crossmatching, and arterial blood gas (ABG) levels.

Monitor the patient’s cardiac rhythm strip. Insert an arterial line to allow for continuous blood pressure monitoring. Assist with insertion of a pulmonary artery line to monitor for hemodynamic balance.

Give drugs, such as an antihypertensive and a beta-adrenergic receptor blocker to control aneurysm progression and an analgesic to relieve pain.

Look for signs of rupture, which may be immediately fatal. Watch closely for signs of acute blood loss (such as decreasing blood pressure, increasing pulse and respiratory rates, restlessness, decreased sensorium, and cool, clammy skin).

If rupture occurs, get the patient to surgery immediately. Medical antishock trousers may be used while transporting him to surgery.

AFTER SURGERY

With the patient in the ICU, closely monitor vital signs, intake and hourly output, neurologic status (such as LOC, pupil size, and sensation in arms and legs), and ABG levels.

Assess fluid status, and replace fluids as needed to ensure adequate hydration.

Watch for signs of bleeding (such as increased pulse and respiratory rates, and hypotension), which may occur retroperitoneally from the graft site.

Check abdominal dressings for excessive bleeding or drainage. Assess the wound site for evidence of infection. Be alert for temperature elevations and other signs of infection. Use sterile technique to change dressings.

DISCHARGE TEACHING

TEACHING THE PATIENT WITH AN ABDOMINAL AORTIC ANEURYSM

TEACHING THE PATIENT WITH AN ABDOMINAL AORTIC ANEURYSM

Review incisional care.

Instruct the patient to look at his incision daily and report any signs or symptoms of infection to the surgeon.

Make sure the patient knows when to see the surgeon for follow-up care.

Instruct the patient to take all drugs as prescribed and to carry a list of drugs at all times, in case of an emergency.

Tell the patient not to push, pull, or lift heavy objects until the practitioner indicates that it’s okay to do so.

After nasogastric intubation for intestinal decompression, irrigate the tube frequently to ensure patency. Record the amount and type of drainage.

Large amounts of blood may be needed during the resuscitative period to replace blood loss. Thus, renal failure due to ischemia is a major postoperative complication, possibly requiring hemodialysis.

RED FLAG

RED FLAGAssess for return of severe back pain, which can indicate that the graft is tearing.

Mechanical ventilation is required after surgery. Assess the depth, rate, and character of respirations and breath sounds at least every hour. Have the patient cough, or suction the endotracheal tube, as needed, to maintain a clear airway. If the patient can breathe unassisted and has good breath sounds and adequate ABG levels, tidal volume, and vital capacity 24 hours after surgery, he will be extubated and will require oxygen by mask.

Weigh the patient daily to evaluate fluid balance.

Provide frequent turning, and help the patient walk as soon as he’s able (generally the second day after surgery). (See Teaching the patient with an abdominal aortic aneurysm.)

FEMORAL AND POPLITEAL ANEURYSMS

Because femoral and popliteal aneurysms occur in the two major peripheral arteries, they’re also known as peripheral arterial aneurysms.

This condition is most common in men older than age 50. Elective surgery before complications arise greatly improves the prognosis.

Causes

Femoral and popliteal aneurysms may be fusiform (spindle-shaped) or saccular (pouchlike). Fusiform types are three times more common. Aneurysms may be singular or multiple segmental lesions, in many instances affecting both legs, and may accompany other arterial aneurysms located in the abdominal aorta or iliac arteries.

Femoral and popliteal aneurysms usually result from progressive atherosclerotic changes in the arterial walls (medial layer). Rarely, they result from congenital weakness in the arterial wall. They may also result from blunt or penetrating trauma, bacterial infection, or peripheral vascular reconstructive surgery (which causes pseudoaneurysms, also called false aneurysms, where a blood clot forms a second lumen).

Complications

Thrombosis

Emboli

Gangrene

Poor tissue perfusion to areas distal to the aneurysm may require amputation

Assessment findings

The patient may report pain in the popliteal space when a popliteal aneurysm is large enough to compress the medial popliteal nerve.

Inspection may reveal edema and venous distention if the vein is compressed.

Femoral and popliteal aneurysms can produce signs and symptoms of severe ischemia in the leg or foot resulting from acute thrombosis within the aneurysmal sac, embolization of mural thrombus fragments and, rarely, rupture.

A patient with acute aneurysmal thrombosis may report severe pain.

Inspection may reveal distal petechial hemorrhages from aneurysmal emboli. The affected leg or foot may show loss of color.

Palpation of the affected leg or foot may indicate coldness and a loss of pulse. Gangrene may develop.

Bilateral palpation that reveals a pulsating mass above or below the inguinal ligament in femoral aneurysm and behind the knee in popliteal aneurysm usually confirms the diagnosis. When thrombosis has occurred, palpation detects a firm, nonpulsating mass.

DISCHARGE TEACHING

TEACHING THE PATIENT WITH FEMORAL AND POPLITEAL ANEURYSM

TEACHING THE PATIENT WITH FEMORAL AND POPLITEAL ANEURYSM

Tell the patient to report recurrence of symptoms immediately because the saphenous vein graft replacement can fail or another aneurysm may develop.

Explain to the patient with popliteal artery resection that swelling may persist for some time. If using antiembolism stockings, make sure they fit properly, and teach the patient how to apply them. Warn against wearing constrictive apparel.

If the patient is receiving an anticoagulant, suggest measures to prevent accidental bleeding such as using an electric razor. Tell the patient to report signs of bleeding immediately (for example, bleeding gums, tarry stools, and easy bruising). Explain the importance of follow-up blood studies to monitor anticoagulant therapy. Warn the patient to avoid trauma, tobacco, and aspirin.

Diagnostic test results

Arteriography or ultrasonography may help resolve doubtful situations. Arteriography may also detect associated aneurysms, especially those in the abdominal aorta and the iliac arteries.

Ultrasonography may also help determine the size of the femoral or popliteal artery.

Treatment

Femoral and popliteal aneurysms require surgical bypass and reconstruction of the artery, usually with an autogenous saphenous vein graft replacement. Arterial occlusion that causes severe ischemia and gangrene may require leg amputation.

Nursing interventions

BEFORE ARTERIAL SURGERY

Assess and record the patient’s circulatory status, noting the location and quality of peripheral pulses in the affected leg.

Give a prophylactic antibiotic or anticoagulant.

Discuss expected postoperative procedures, review the explanation of the surgery, and answer the patient’s questions.

AFTER ARTERIAL SURGERY

Carefully monitor the patient for early signs and symptoms of thrombosis or graft occlusion (such as loss of pulse, decreased skin temperature and sensation, and severe pain) and infection (such as fever).

Palpate distal pulses at least every hour for the first 24 hours and then as often as ordered. Correlate these findings with the preoper-ative circulatory assessment. Mark the sites on the patient’s skin where pulses are palpable to facilitate repeated checks.

Help the patient walk soon after surgery to prevent venous stasis and, possibly, thrombus formation. (See Teaching the patient with femoral and popliteal aneurysm.)

PERIPHERAL ARTERIAL OCCLUSIVE DISEASE

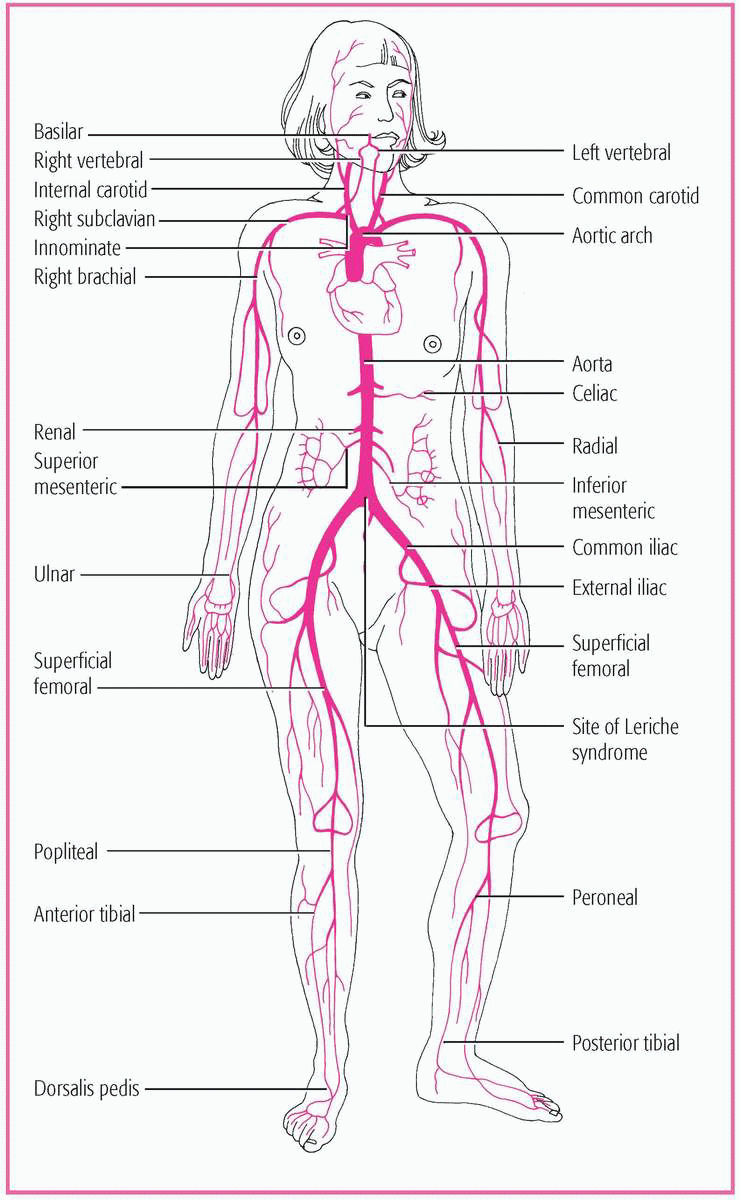

Peripheral arterial occlusive disease is an obstruction or narrowing of the lumen of the aorta and its major branches, which interrupts blood flow, usually to the legs and feet. Arterial occlusive disease may affect the carotid, vertebral, innominate, subclavian, mesenteric, and celiac arteries. (See Possible sites of major artery occlusion, page 452.)

Peripheral arterial occlusive disease is more common in men than in women. The prognosis depends on the location of the occlusion, the development of collateral circulation to counteract reduced blood flow and, in patients with acute disease, the time elapsed between the development of the occlusion and its removal.

Pathophysiology

Peripheral arterial occlusive disease is almost always the result of atherosclerosis in which fatty, fibrous plaques narrow the lumen of blood vessels. This occlusion can occur acutely or progressively over 20 to 40 years, with areas of vessel branching, or bifurcation, being the most common sites. The narrowing of the lumens reduces the blood volume that can flow through them, causing arterial insufficiency to the affected area. Ischemia usually occurs after the vessel lumens have narrowed by at least 50%, reducing blood flow to levels which no longer meet the needs of tissues and nerves.

Arterial occlusive disease is a common complication of atherosclerosis. The occlusive mechanisms may be endogenous, due to emboli formation or thrombosis, or exogenous, due to trauma or fracture. (See What causes acute arterial occlusion? page 453.)

Predisposing factors include smoking; aging; conditions such as hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and diabetes mellitus; and family history of vascular disorders, myocardial infarction, or stroke.

AGE AWARE

AGE AWAREAging causes sclerotic changes in blood vessels, which leads to decreased elasticity and narrowing of the lumen, further contributing to the development of peripheral arterial occlusive disease. In people older than age 70, the prevalence of the disease is estimated to be 10% to 18%.

WHAT CAUSES ACUTE ARTERIAL OCCLUSION?

The most common cause of acute arterial occlusion is obstruction of a major artery by a clot. The occlusive mechanism may be endogenous, resulting from emboli formation, thrombosis, or plaques, or exogenous, resulting from trauma or fracture.

Embolism

Often the obstruction results from an embolus originating in the heart. Emboli typically lodge in the arms and legs, where blood vessels narrow or branch. In the arms, emboli usually lodge in the brachial artery but may occlude the subclavian or axillary arteries. Common leg sites include the iliac, femoral, and popliteal arteries. Emboli originating in the heart can cause neurologic damage if they enter the cerebral circulation.

Thrombosis

In a patient with atherosclerosis and marked arterial narrowing, thrombosis may cause acute intrinsic arterial occlusion. This complication typically arises in areas with severely stenotic vessels, especially in a patient who also has heart failure, hypovolemia, polycythemia, or traumatic injury.

Plaques

Atheromatous debris (plaques) from proximal arterial lesions may also intermittently obstruct small vessels (usually in the hands or feet). These plaques may also develop in the brachiocephalic vessels and travel to the cerebral circulation, where they may lead to transient cerebral ischemia or infarction.

Exogenous causes

Acute arterial occlusion may stem from insertion of an indwelling arterial catheter or intra-arterial drug abuse.

Extrinsic arterial occlusion can also result from direct blunt or penetrating trauma to the artery.

Complications

Severe ischemia and necrosis

Skin ulceration

Gangrene, which can lead to limb amputation

Impaired nail and hair growth

Stroke or transient ischemic attack

Peripheral or systemic embolism

Assessment findings

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree