Two leaflets: anterior leaflet (is in fibrous continuity with aortic valve annulus) and posterior leaflet—competency depends on large-zone coaptation—supported by annulus, posteromedial and anterolateral papillary muscles coming off left ventricle (LV) free wall and septum, and tendinae chordae: changes in any of above can result in mitral regurgitation (MR).

The posterior leaflet is divided into three segments by scallops; the anterior leaflet not scalloped—segments are based on which parts are opposite the posterior scallops, and each commissure is a segment, so P2 refers to the middle scallop of the posterior leaflet.

The posteromedial papillary muscle is supplied by the circumflex or posterior descending coronary artery and is most prone to ischaemic rupture, causing flail posterior leaflet (compared to the anterolateral papillary muscle which has a dual supply).

Posterior regurgitant jet is caused by posterior leaflet restriction (common) or anterior leaflet prolapse (unusual), and an anteriorly directed jet is due to posterior leaflet prolapse (most common) or anterior leaflet restriction (unusual). Central leaks come from annular dilatatation. Eccentric jets often lead to commissural prolapse.

Trileaflet valve (right and left coronary cusps based on the location of the coronary ostia, and non-coronary cusp), with small-zone coaptation.

Increase in size of annulus, sinuses, sinotubular junction, or leaflet destruction can result in aortic insufficiency (AI).

Conduction tissue runs between the right and non-coronary cusp.

Three leaflets (septal, anterior and posterior) with a moderate zone of coaptation. The posterior and anterior annulus are most prone to dilatation.

Atrioventricular (AV) node tissue is located just below the anteroseptal commissure.

<1:1000 in developed countries; 10:1000 schoolchildren in developing countries. It is rarer, but still accounts for half of cardiac disease in the developing world.

Declining incidence is due to improved economic standards and housing, decreased crowding, and access to medical care and antimicrobials.

Typically affects children aged 5-15 years from lower socio-economic class living in crowded conditions; 20% of cases are in adults. Incidence is higher in native Hawaiians and Maoris despite antibiotic prophylaxis.

No sex difference but chorea and mitral stenosis (MS) are more common in females.

Typically occurs several weeks after a streptococcal pharyngitis. Usually group A beta haemolytic streptococci: Streptococcus pyogenes serotype M. Antigenic mimicry is implicated—antibodies to carbohydrate in cell wall (anti-M antibodies) of group A Streptococcus cross-react with protein in cardiac valves.

Delay from acute infection to onset of rheumatic fever (RF) is usually 3-4 weeks. RF is thought to complicate up to 3% of untreated streptococcal sore throats. Previous episodes of RF predispose to further events (up to 50% of streptococcal sore throat is complicated by RF if there has been a previous episode). Other areas of crossreactivity may explain other signs (e.g. involvement of connective tissue in joints—arthritis, caudate nucleus in brain—Sydenham’s chorea).

Commonly causes a pancarditis. Pericarditis can cause haemodynamic instability or constriction. Myocarditis may cause acute heart failure and arrhythmias. Endocarditis affects the mitral valve (65-70%), aortic valve (25%), and tricuspid valve (10%, never in isolation) causing acute regurgitation and heart failure, and eventually chronic stenosis.

Pericardium, perivascular regions of myocardium, and endocardium develop perivascular foci of eosinophilic collagen surrounded by lymphocytes, plasma cells, and macrophages called Aschoff bodies.

Sore throat 1-5 weeks earlier is reported in two-thirds of cases.

Fever, abdominal pain, and epistaxis.

Migratory large-joint polyarthritis starting in the lower limbs in 75% of cases. Duration less than 4 weeks at each site. Severe pain and tenderness in contrast to degree of joint swelling.

Pancarditis in 50% of cases with features of acute heart failure, mitral and aortic regurgitation, an apical, mid-diastolic flow murmur (Carey Coombs murmur), and pericarditis.

Chorea in 10-30%, usually 1-6 months after the index pharyngitis. Difficulty writing and speaking, generalized weakness, choreiform movements, and emotional lability. Joints hyperextended with hypotonia, diminished tendon reflexes, tongue fasciculation, and a

relapsing grip (alternate increases/decreases in tension). Recovery 2-3 months.

Erythema marginatum is an evanescent rash with serpiginous outlines and central clearings on the trunk and proximal limbs. Seen in 5-13% of cases. Begins as erythematous, non-pruritic papules or macules that spread outwards. Fades and reappears in hours and persists.

Subcutaneous nodules in 0-8% of cases several weeks after the onset of severe pancarditis. Mainly over bony surfaces or prominences and tendons. Commonly involves the elbows, knees, wrists, ankles, Achilles tendons, occiput, and vertebral spinous processes. Duration 1-2 weeks.

There is a danger of overdiagnosing RF in children admitted with fever, soft murmurs, and arthralgia, all of which are common in childhood.

Table 3.1 Treatment of rheumatic fever | ||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Determined by level of cardiac involvement and antibiotic prophylaxis (5 years or until 21 years old if no carditis, 10 years or well into adulthood if carditis but no valve disease, 10 years or until 40 years old if valves affected and for all dental and surgical procedures).

Acute phase duration about 3 months in 80% of cases. Mortality 1-10% in developing countries.

Recurrence rates are high. Chronic valve disease occurs in one-third without and two-thirds with recurrent infections.

Murmurs resolve in 50% of cases up to 5 years after index infection.

Dyspnoea on exertion, orthopnoea, paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnoea.

Acute pulmonary oedema may be precipitated by uncontrolled AF, exercise, chest infection, anaesthesia, and pregnancy.

AF increases the risk of thromboembolism. Systemic embolism occurs in 20-30% and usually originates in the dilated LA and LA appendage.

Fatigue is due to reduced cardiac output reserve and is common in mild-moderate stenosis.

Haemoptysis can occur for a variety of reasons: alveolar capillary rupture (pink frothy pulmonary oedema); bronchial vein rupture (larger haemorrhage); blood-stained sputum of chronic bronchitis; pulmonary infarction (low CO, immobile patients).

Chest pain similar to angina may occur in patients with pulmonary hypertension and RV hypertrophy, even with normal coronaries.

Rarely, the enlarging LA may compress surrounding structures producing a hoarse voice (left recurrent laryngeal nerve compression— Ortner’s syndrome), dysphagia (oesophageal compression), left lung collapse (left main bronchus compression).

Electrocardiography (ECG): P mitrale—bifid P wave (if in sinus rhythm) due to LA enlargement most prominent in lead II. Tall and peaked P waves in pulmonary hypertension. AF is frequent. Right-axis deviation and RV hypertrophy.

Chest X-ray (CXR): Straightening of the left heart border, prominent upper lobe veins, pulmonary artery enlargement, Kerley B lines—interstitial oedema. Large LA visible as a double shadow.

Radiographic features of mitral stenosis

PA film

Lateral film

• Straight or convex L heart border

• Valvular calcification frequent

• Splaying of carina (>90°)—rare

• Dilated upper lobe veins

• LA calcification seen rarely (McCallum’s patch)

• Prominent pulmonary conus

• Oesophageal indentation on barium swallow

• Pulmonary haemosiderosis

Transthoracic ECHO (TTE): Parasternal long-axis view (LAX) shows enlarged LA and doming of the valve leaflets due to commissural fusion. In short-axis view (SAX), the mitral valve orifice can be calculated by planimetry. Calcification can be visualized. M-mode imaging—restricted valve leaflet separation due to commissural fusion. Continuous wave (CW) Doppler can be used to estimate the valve area and transvalvular gradient (see p. 15). Valve ECHO score can be calculated (based on leaflet mobility, leaflet thickening, subvalvular thickening, and calcification).

p. 15). Valve ECHO score can be calculated (based on leaflet mobility, leaflet thickening, subvalvular thickening, and calcification).

Transoesophageal echocardiography (TOE): Provides better anatomic detail, can visualize small vegetations and thrombi in the LA.

Cardiac catheterization: Increased pulmonary capillary wedge pressure (PCWP). Increased PCWP to LV end-diastolic pressure gradient. If the mean mitral gradient is low at rest, get the patient to perform exercise on the cath-lab table (e.g. straight-leg raising) to calculate gradient again. Assessment of co-existing coronary and valvular lesions.

Mild symptoms: salt intake restriction and oral diuretics (cautious).

In AF: digoxin, β-blocker, or calcium-channel blocker for rate control. Restoration of sinus rhythm may be attempted if appropriate.

Anticoagulation: recommended for those with AF, prior thromboembolism, or LA thrombus. Patients with low-output states, right heart failure, or LA dimension ≥55 mm by echocardiography should also be anticoagulated. There is no proven benefit if the patient is in sinus rhythm.

Endocarditis prophylaxis is no longer recommended.1

Suitable for patients with pliable valves with minimal MR, no subvalvular distortion, and without heavy calcification (ideal if valve score ≤8).

Contraindicated in moderate or severe MR or atrial thrombus.

A guide wire is placed in the LA after trans-septal puncture, and a balloon (Inoue balloon) is directed across the valve and inflated at the orifice.

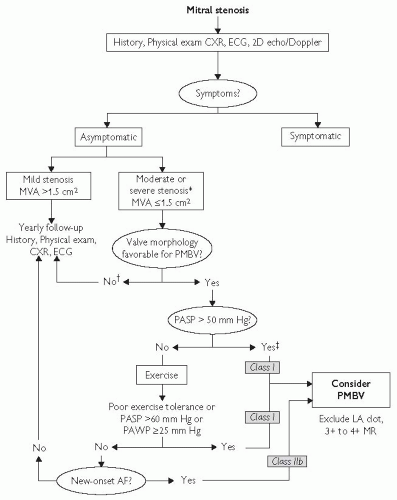

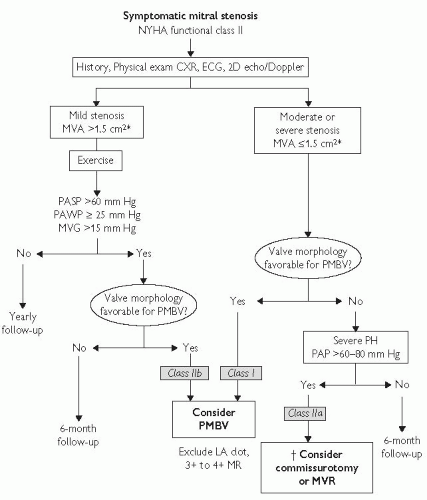

Indicated when morphology is not conducive to percutaneous balloon valvotomy (see algorithms in Figs 3.2 and 3.3).

Closed valvotomy: fused cusps separated by a dilator introduced through LV apex. No longer recommended.

Open valvotomy with cardiopulmonary bypass is preferred to closed valvotomy. Cusps are separated under direct vision. Any fusion of subvalvular apparatus is loosened.

Mitral repair is occasionally possible in advanced rheumatic stenosis using pericardium to augment leaflets, but durability is 5-10 years.

Mitral valve replacement if repair is not possible:

2-4% annual risk of major thromboembolic or haemorrhagic event, including stroke with mechanical valve (so very high lifetime risk in young patients), and small risk of reoperation for non-structural valve dysfunction

third-generation bioprosthetic valves’ durability is dependent on age of patient—around 80% freedom from structural valve degeneration at 10 years in 40-50 year olds, versus over 90% freedom at 10 years in >65 year olds

Risk of surgery: 1-2% mortality and stroke in 65-year-old patient with no other major morbidity and good LV function.

Fig. 3.2 Management strategy for patients with mitral stenosis. *The writing committee recognizes that there may be variability in the measurement of mitral valve area (MVA) and that the mean transmitral gradients, pulmonary artery wedge pressure (PAWP), and pulmonary artery systolic pressure (PASP) should also be taken into consideration. †There is controversy as to whether patients with severe mitral stenosis (MVA less than 1.0 cm2) and severe pulmonary hypertension (pulmonary artery pressure greater than 60 mm Hg) should undergo percutaneous mitral balloon valvotomy (PMBV) or mitral valve replacement to prevent right ventricular failure. ‡Assuming no other cause for pulmonary hypertension is present. AF indicates atrial fibrillation; CXR, chest X-ray; ECG, electrocardiogram; echo, echocardiography; LA, left atrial; MR, mitral regurgitation; and 2D, 2-dimensional. Reproduced with permission from Journal of the American College of Cardiology, Vol 48, No.3, 2006. August 1, 2006:e1-148. Bonow et al, AHA/ACC Best Practice Guidelines. |

Fig. 3.3 Management strategy for patients with mitral stenosis and mild symptoms. *The committee recognizes that there may be variability in the measurement of mitral valve area (MVA) and that the mean transmitral gradient, pulmonary artery wedge pressure (PAWP), and pulmonary artery systolic pressure (PASP) should also be taken into consideration. †There is controversy as to whether patients with severe mitral stenosis (MVA less than 1.0 cm2) and severe pulmonary hypertension (PH; PASP greater than 60 to 80 mm Hg) should undergo percutaneous mitral balloon valvotomy (PMBV) or mitral valve replacement (MVR) to prevent right ventricular failure. CXR indicates chest X-ray; ECG, electrocardiogram; echo, echocardiography; LA, left atrial; MR, mitral regurgitation; MVG, mean mitral valve pressure gradient; NYHA, New York Heart Association; PAP, pulmonary artery pressure; and 2D, 2-dimensional. Reproduced with permission from Journal of the American College of Cardiology, Vol 48, No.3, 2006. August 1, 2006:e1-148. Bonow et al, AHA/ACC Best Practice Guidelines. |

Essentially there is a spectrum of myxomatous degenerative disease from single-segment prolapse in small valves (fibroelastic deficiency) to multisegment prolapse in large valves (Barlow’s disease).

Mitral regurgitation (MR) can be classified by mechanism according to Carpentier’s classification:

type I—normal leaflet motion, e.g. dilated annulus from dilated cardiomyopathy, leaflet perforation due to endocarditis

type II—leaflet prolapse, e.g. myxomatous degeneration

type IIIa—restricted leaflet opening, e.g. rheumatic disease

type IIIb—restricted leaflet closing, e.g. ischaemic dilated cardiomyopathy (functional).

In acute MR:

there is little enlargement of the LA due to normal compliance. This results in raised LA pressure and can result in pulmonary oedema

In longstanding severe MR, there is enlargement of the LA, which accommodates the volume overload with minimal rise in LA pressure. The LV dilates, and large stroke volume compensates for regurgitation, maintaining the forward EF. LV failure results from longstanding volume overload. The low-pressure regurgitant pathway masks LV failure: EF is often normal even when LV is very impaired.

p. 728.

p. 728.

ECG: LA enlargement, left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH), RA enlargement in pulmonary hypertension. AF common in chronic MR.

CXR: Cardiomegaly, LA and LV enlargement, and pulmonary venous congestion. Calcified mitral annulus may be seen.

TTE: Demonstrates MV anatomy (lesion and type of MR). Colour Doppler to detect and quantify the MR (Table 3.3). Assessment of LV function from EF, end-systolic dimension and end-diastolic dimension (Note: In compensated MR, EF is always overestimated because of the low-resistance retrograde pathway).

TOE: Shows the anatomy in greater detail and allows accurate assessment of the feasibility of valve repair. Should be performed pre- or intra-operatively.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree