Valvular Disorders

AORTIC INSUFFICIENCY

Aortic insufficiency by itself occurs most commonly in men. When associated with mitral valve disease, however, it’s more common in women. This disorder may also be associated with Marfan syndrome, ankylosing spondylitis, syphilis, essential hypertension, and a ventricular septal defect, even after surgical closure.

Pathophysiology

In patients with aortic insufficiency (also called aortic regurgitation), blood flows back into the left ventricle during diastole. The ventricle becomes overloaded, dilated, and eventually hypertrophies. The excess fluid volume also overloads the left atrium and, eventually, the pulmonary system.

Aortic insufficiency results from rheumatic fever, syphilis, hypertension, endocarditis, or trauma. In some patients, it may be idiopathic.

Complications

Left-sided heart failure

Fatal pulmonary edema resulting from fever, infection, or cardiac arrhythmia

Myocardial ischemia (left ventricular dilation and elevated left ventricular systolic pressure alter myocardial oxygen requirements)

Assessment findings

A patient with chronic severe aortic insufficiency may report that he has an uncomfortable awareness of his heartbeat, especially when lying down on his left side.

He may report palpitations along with a pounding head.

The patient may experience exertional dyspnea and paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea with diaphoresis, orthopnea, and cough.

He may become fatigued and syncopal with exertion or emotion.

He may also have a history of angina unrelieved by sublingual nitroglycerin.

On inspection, you may note that each heartbeat seems to jar the patient’s entire body and that his head bobs with each systole.

Inspection of arterial pulsations shows a rapidly rising pulse that collapses suddenly as arterial pressure falls late in systole.

The patient’s nail beds may appear to be pulsating. If you apply pressure at the nail tip, the root will alternately flush and pale.

Inspection of the chest may reveal a visible apical pulse.

If the patient has left-sided heart failure, he may have ankle edema and ascites.

When palpating the peripheral pulses, you may note rapidly rising and collapsing pulses (called pulsus biferiens). If the patient has cardiac arrhythmias, pulses may be irregular. You’ll be able to feel the apical impulse. (The apex is displaced laterally and inferiorly.) A diastolic thrill probably is palpable along the left sternal border, and you may be able to feel a prominent systolic thrill in the jugular notch and along the carotid arteries.

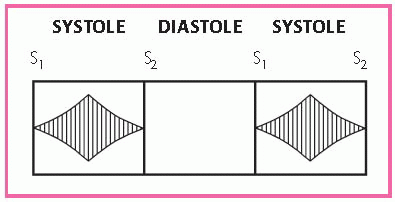

Auscultation may reveal an S3, occasionally an S4, and a loud systolic ejection sound. A high-pitched, blowing, decrescendo diastolic murmur is best heard at the left sternal border, at the third intercostal space. Use the diaphragm of the stethoscope to hear it, and have the patient sit up, lean forward, and hold his breath in forced expiration. (See Identifying the murmur of aortic insufficiency.)

You may also hear a grade 5 or 6 midsystolic ejection murmur at the base of the heart, typically higher pitched, shorter, and less rasping than the murmur heard in aortic stenosis.

Another murmur that may occur is a soft, low-pitched, rumbling, middiastolic or presystolic bruit; this murmur is best heard at the base of the heart.

Place the stethoscope lightly over the femoral artery to hear a booming, pistol-shot sound and a to-and-fro murmur.

Arterial pulse pressure is widened.

Auscultating blood pressure may be difficult because you can hear the patient’s pulse after you inflate the cuff. To determine systolic pressure, note when Korotkoff sounds begin to muffle.

Diagnostic test results

Cardiac catheterization shows reduced arterial diastolic pressures, aortic insufficiency, other valvular abnormalities, and increased left ventricular end-diastolic pressure.

Chest X-rays display left ventricular enlargement and pulmonary vein congestion.

Echocardiography reveals left ventricular enlargement, dilation of the aortic annulus and left atrium, and thickening of the aortic valve. It also reveals a rapid, high-frequency fluttering of the anterior mitral leaflet that results from the impact of aortic insufficiency.

Electrocardiography shows sinus tachycardia, left ventricular hypertrophy, and left atrial hypertrophy in patients with severe disease. ST-segment depressions and T-wave inversions appear in leads I, aVL, V5, and V6 and indicate left ventricular strain.

Treatment

Valve replacement is the treatment of choice and should be performed before significant ventricular dysfunction occurs. This may be impossible, however, because signs and symptoms seldom occur until after myocardial dysfunction develops.

A cardiac glycoside, a low-sodium diet, a diuretic, a vasodilator and, especially, an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor are used to treat patients with left-sided heart failure. For acute episodes, supplemental oxygen may be necessary.

Nursing interventions

If the patient needs bed rest, stress its importance. Assist with bathing if necessary. Provide a bedside commode because using a

commode puts less stress on the heart than using a bedpan. Offer the patient diversionary, physically undemanding activities.

Alternate periods of activity with periods of rest to prevent extreme fatigue and dyspnea.

To reduce anxiety, allow the patient to express his concerns about the effects of activity restrictions on his responsibilities and routines. Reassure him that the restrictions are temporary.

Keep the patient’s legs elevated while he sits in a chair to improve venous return to the heart.

Place the patient in an upright position to relieve dyspnea, if necessary, and administer oxygen to prevent tissue hypoxia.

Keep the patient on a low-sodium diet. Consult a dietitian to ensure that the patient receives foods that he likes while adhering to diet restrictions. (See Teaching the patient with aortic insufficiency.)

Monitor the patient for signs of heart failure, pulmonary edema, and adverse reactions to drug therapy.

Monitor his vital signs, arterial blood gas level, intake and output, daily weight, blood chemistry results, chest X-ray, and pulmonary artery catheter readings.

DISCHARGE TEACHING

TEACHING THE PATIENT WITH AORTIC INSUFFICIENCY

TEACHING THE PATIENT WITH AORTIC INSUFFICIENCY

Advise the patient to plan for periodic rest in his daily routine to prevent undue fatigue.

Teach the patient about diet restrictions, drugs, signs and symptoms that should be reported, and the importance of consistent follow-up care.

Tell the patient to elevate his legs whenever he sits.

RED FLAG

RED FLAGIf the patient undergoes surgery, watch for hypotension, arrhythmias, and thrombus formation.

AORTIC STENOSIS

Aortic stenosis is hardening of the aortic valve or of the aorta itself. About 80% of patients with aortic stenosis are male.

Pathophysiology

In aortic stenosis, the opening of the aortic valve narrows, and the left ventricle exerts increased pressure to drive blood through the opening. The added workload increases the demand for oxygen, and diminished cardiac output reduces coronary artery perfusion, causes ischemia of the left ventricle, and leads to heart failure.

Aortic stenosis may result from congenital aortic bicuspid valve (from coarctation of the aorta), congenital stenosis of pulmonic valve cusps, rheumatic fever or, in elderly patients, atherosclerosis.

Complications

Left-sided heart failure, usually after age 70, within 4 years after the onset of signs and symptoms; fatal in up to two-thirds of patients

Sudden death, usually around age 60, in 20% of patients, possibly caused by an arrhythmia

Assessment findings

Even with severe aortic stenosis (narrowing to about one-third of the normal opening), the patient may be asymptomatic.

The patient may complain of exertional dyspnea, fatigue, exertional syncope, angina, and palpitations.

If left-sided heart failure develops, the patient may complain of orthopnea and paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea.

Inspection may reveal peripheral edema if the patient has left-sided heart failure.

Palpation may detect diminished carotid pulses and alternating pulses. If the patient has left-sided heart failure, the apex of the heart may be displaced inferiorly and laterally. If the patient has pulmonary hypertension, you may be able to palpate a systolic thrill at the base of the heart, at the jugular notch, and along the carotid arteries. Occasionally, it may be palpable only during expiration and when the patient leans forward.

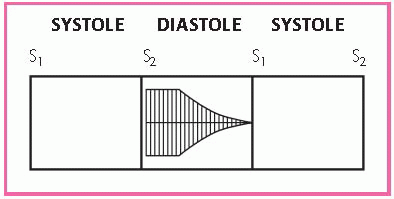

Auscultation may uncover an early systolic ejection murmur in children and adolescents who have noncalcified valves. The murmur begins shortly after S1 and increases in intensity to reach a peak toward the middle of the ejection period. It diminishes just before the aortic valve closes. (See Identifying the murmur of aortic stenosis.)

The murmur is low-pitched, rough, and rasping and is loudest at the base at the second intercostal space. In patients with stenosis, the murmur is at least grade 3 or 4. It disappears when the valve calcifies. A split S2 develops as aortic stenosis becomes more severe. An S4 reflects left ventricular hypertrophy and may be heard at the apex in patients with severe aortic stenosis.

Diagnostic test results

Cardiac catheterization reveals the pressure gradient across the valve (indicating the severity of the obstruction), increased left ventricular end-diastolic pressures (indicating left ventricular function), and the location of the left ventricular outflow obstruction.

Chest X-rays show valvular calcification, left ventricular enlargement, pulmonary vein congestion and, in later stages, left atrial, pulmonary arterial, right atrial, and right ventricular enlargement.

Echocardiography demonstrates a thickened aortic valve and left ventricular wall and, possibly, coexistent mitral valve stenosis.

Electrocardiography reveals left ventricular hypertrophy. In advanced stages, the patient exhibits ST-segment depression and T-wave inversion in standard leads I and aVL and in the left precordial leads. Up to 10% of patients have atrioventricular and intraventricular conduction defects.

Treatment

A cardiac glycoside, a low-sodium diet, a diuretic and, for acute cases, oxygen are used to treat patients with heart failure. Nitroglycerin helps to relieve angina.

AGE AWARE

AGE AWAREFor children who don’t have calcified valves, simple commissurotomy under direct visualization is usually effective.

Adults with calcified valves need valve replacement when they become symptomatic or are at risk for developing left-sided heart failure.

Percutaneous balloon aortic valvuloplasty is useful in a child or young adult with congenital aortic stenosis and in an elderly patient with severe calcifications. This procedure may improve left ventricular function so the patient can tolerate valve replacement surgery.

A Ross procedure is usually performed in patients younger than age 55. During this procedure, the pulmonic valve is used to replace the aortic valve, and the pulmonic valve of a cadaver is inserted. This allows longer valve life and makes anticoagulant therapy unnecessary.

Nursing interventions

If the patient needs bed rest, stress its importance. Assist the patient with bathing if necessary; provide a bedside commode because using a commode puts less stress on the heart than using a bedpan. Offer the patient diversionary, physically undemanding activities.

Alternate periods of activity with periods of rest to prevent extreme fatigue and dyspnea.

To reduce anxiety, allow the patient to express his concerns about the effects of activity restrictions on his responsibilities and routines. Reassure him that the restrictions are temporary.

Keep the patient’s legs elevated while he sits in a chair to improve venous return to the heart.

Place the patient in an upright position to relieve dyspnea, if needed. Administer oxygen to prevent tissue hypoxia, as needed.

Keep the patient on a low-sodium diet. Consult with a dietitian to ensure that the patient receives foods that he likes while adhering to diet restrictions. (See Teaching the patient with aortic stenosis.)

Monitor the patient for signs of heart failure, pulmonary edema, and adverse reactions to drug therapy.

Allow the patient to express his fears and concerns about the disorder, its impact on his life, and any upcoming surgery. Reassure him as needed.

After cardiac catheterization, apply firm pressure to the catheter insertion site, usually in the groin. Monitor the site every 15 minutes for at least 6 hours for signs of bleeding. If the site bleeds, remove the pressure dressing and apply firm pressure.

Notify the practitioner of any changes in peripheral pulses distal to the insertion site, changes in cardiac rhythm and vital signs, and complaints of chest pain.

Monitor vital signs, arterial blood gas levels, intake and output, daily weight, blood chemistry results, chest X-rays, and pulmonary artery catheter readings.

DISCHARGE TEACHING

TEACHING THE PATIENT WITH AORTIC STENOSIS

TEACHING THE PATIENT WITH AORTIC STENOSIS

Advise the patient to plan for periodic rest in his daily routine to prevent undue fatigue.

Teach the patient about diet restrictions, drugs, signs and symptoms that should be reported, and the importance of consistent follow-up care.

Tell the patient to elevate his legs whenever he sits.

RED FLAG

RED FLAGIf the patient has surgery, watch for hypotension, arrhythmias, and thrombus formation.

MITRAL INSUFFICIENCY

Mitral insufficiency—also known as mitral regurgitation—occurs when a damaged mitral valve allows blood from the left ventricle to flow back into the left atrium during systole.

Pathophysiology

In mitral insufficiency, blood from the left ventricle flows back into the left atrium during systole. As a result, the atrium enlarges to accommodate the backflow. The left ventricle also dilates to accommodate the increased volume of blood from the atrium and to compensate for diminishing cardiac output.

Mitral insufficiency tends to be progressive because left ventricular dilation increases the insufficiency, which further enlarges the left atrium and ventricle, which further increases the insufficiency.

Damage to the mitral valve can result from rheumatic fever, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, mitral valve prolapse, a myocardial infarction, severe left-sided heart failure, or ruptured chordae tendineae.

In older patients, mitral insufficiency may occur because the mitral annulus has become calcified. The cause is unknown, but it may

be linked to a degenerative process. Mitral insufficiency is sometimes associated with congenital anomalies such as transposition of the great arteries.

be linked to a degenerative process. Mitral insufficiency is sometimes associated with congenital anomalies such as transposition of the great arteries.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

AGE AWARE

AGE AWARE