The 2013 American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association guidelines recommend combined isosorbide dinitrate (ISDN) and hydralazine to reduce mortality and morbidity for African-Americans with symptomatic heart failure (HF) and reduced ejection fraction, currently receiving optimal medical therapy (class I, level A). Nitrates can alleviate HF symptoms, but continuous use is limited by tolerance. Hydralazine may mitigate nitrate tolerance, and the ISDN–hydralazine combination in the Vasodilators in Heart Failure Trial (V-HeFT) I improved survival and exercise tolerance in men with dilated cardiomyopathy or HF with reduced ejection fraction, most notably in self-identified black participants. In the subsequent V-HeFT II, survival was greater with enalapril than with ISDN–hydralazine in the overall cohort, but mortality rate was similar in the enalapril and ISDN–hydralazine groups in the self-identified black patients. Consequently, in the African-American Heart Failure Trial (A-HeFT) in self-identified black patients with symptomatic HF, adding a fixed-dose combination ISDN–hydralazine to modern guideline-based care improved outcomes versus placebo, including all-cause mortality, and led to early trial termination. Hypertension underlies HF, especially in African-Americans; the A-HeFT and its substudies demonstrated not only improvements in echocardiographic parameters, morbidity, and mortality but also a decrease in hospitalizations, potentially affecting burgeoning HF health-care costs. Genetic characteristics may, therefore, determine response to ISDN–hydralazine, and the Genetic Risk Assessment in Heart Failure substudy demonstrated important hypothesis-generating pharmacogenetic data.

The 2013 American College of Cardiology Foundation and American Heart Association (AHA) guidelines recommend the combination of isosorbide dinitrate (ISDN) and hydralazine to reduce mortality and morbidity for African-Americans with New York Heart Association class III or IV heart failure (HF) and HF with reduced ejection fraction (EF) who are currently receiving optimal medical therapy with angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and β blockers (class I, level A). The guidelines also state that the combination of ISDN and hydralazine can be useful to reduce morbidity and mortality in patients with current or previous symptomatic HF who are not able to take angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin II receptor blockers (class IIa, level B). Nevertheless, African-Americans remain more likely than whites to die from diseases of the heart ( Figure 1 ), and many patients who may benefit from ISDN–hydralazine are not receiving it. This review details the rationale for using ISDN–hydralazine in African-Americans with HF as discussed at a roundtable meeting of cardiologists in November 2012. As HF is the primary diagnosis in >1 million hospitalizations annually and annual costs related to HF in the United States exceed $40 billion, advances in the treatment of HF would have significant economic benefits.

Rationale for the Study of Isosorbide Dinitrate and Hydralazine in Patients With HF

Organic nitrates, including ISDN, activate the intracellular enzyme soluble guanylyl cyclase and subsequently elevate cyclic guanosine 3′,5′-monophosphate levels. The elevated cyclic guanosine 3′,5′-monophosphate level leads to activation of cyclic guanosine 3′,5′-monophosphate–dependent protein kinase, which in turn mediates vasorelaxation by phosphorylating proteins that regulate intracellular calcium mobilization. However, within several hours of sustained exposure, nitrates (including ISDN) lose efficacy quickly as tolerance develops, leading to marked attenuation of hemodynamic effects.

Hydralazine prevents and reverses nitrate tolerance—preserving its capacity to reduce venous pressure—probably by reducing superoxide production in vascular tissues and possibly also by scavenging reactive oxygen species to mitigate both vascular tolerance and cross-tolerance.

Nitric oxide (NO) is an endogenous vasodilator that also directly affects the myocardium to modulate contractility, diastolic distensibility, mitochondrial respiration, substrate metabolism, ion channel function, cell growth (hypertrophy), and postinfarction remodeling. In the presence of superoxide and other reactive oxygen species, NO is converted to peroxynitrite, reducing its capacity to relax the endothelium. Peroxynitrite itself can interact with proteins and genes to damage the endothelium and elicit endothelial dysfunction.

Data from animal models and clinical studies suggest that correction of NO bioavailability and/or signaling capacity or reduction in oxidative stress favorably alters HF end points. This hypothesis was tested using the combination of ISDN and hydralazine in patients with HF and HF with reduced EF in the Vasodilators in Heart Failure Trial (V-HeFT) I and V-HeFT II.

Isosorbide Dinitrate and Hydralazine in Heart Failure

Compared with placebo, treatment with ISDN and hydralazine reduced the relative risk of death by 36% after 3 years with minimal background therapy (digoxin and diuretics) in V-HeFT I. Furthermore, ISDN and hydralazine improved survival in black or African-American patients, although the effect was not significant in white patients ( Figure 2 ). In V-HeFT II, treatment with ISDN and hydralazine did not improve survival compared with enalapril, although the effects on all-cause mortality were equivalent to those of enalapril in black patients and inferior to enalapril in white patients.

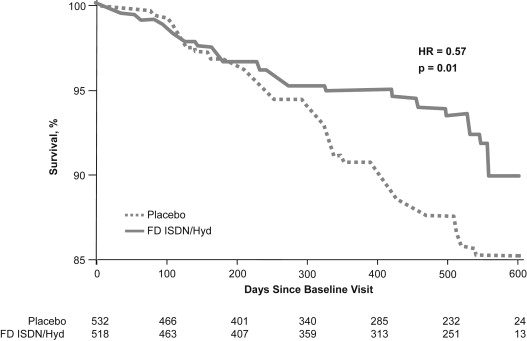

These findings led to the design of an outcomes study with fixed-dose (FD) ISDN–hydralazine (BiDil; Arbor Pharmaceuticals, Inc, Atlanta, Georgia) in self-identified black patients. The African-American Heart Failure Trial (A-HeFT) enrolled 1,050 patients with New York Heart Association class III or IV HF receiving guideline-based care, including β blockers, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, and/or angiotensin II receptor blockers. The primary outcome of A-HeFT was a composite score of mortality, hospitalization, and quality of life (QOL), and the clear survival benefit of FD ISDN–hydralazine over placebo led to termination of the study after 3 years ( Figure 3 ). With a median follow-up period of 10 months, FD ISDN–hydralazine in combination with neurohormonal blockade reduced mortality by 43%. In addition, in A-HeFT, adding FD ISDN–hydralazine to standard therapy decreased the number of hospitalizations and reduced length of hospital stay compared with standard therapy alone. The relative risk of an HF-related hospitalization during the first 2 years of treatment was equal to placebo in V-HeFT I and to enalapril in V-HeFT II. In A-HeFT, improvements in functional parameters included EF, left ventricular (LV) remodeling, and significant reduction in B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP). Additionally, based on the Minnesota Living with Heart Failure questionnaire, patients in A-HeFT reported improved QOL with FD ISDN–hydralazine.

The first hospitalization for HF was a component of the primary composite score in A-HeFT. With a mean follow-up of 10 months (range 0 to 18), 130 patients (24.4%) in the placebo group and 85 (16.4%) in the FD ISDN–hydralazine group (p = 0.001) were hospitalized. Relative risk of first HF hospitalization was reduced by 39% with FD ISDN–hydralazine compared with placebo (hazard ratio 0.61, 95% confidence interval 0.46 to 0.80, p <0.001; Figure 4 ). The treatment effect appeared early, approximately 50 days after starting treatment, and remained significant throughout the study. A similar beneficial effect of FD ISDN–hydralazine was observed in all the subgroups analyzed, including age (< or >65 years), gender, ischemic HF etiology, baseline blood pressure (BP; systolic BP >126 mm Hg), presence of diabetes mellitus, history of chronic renal insufficiency, and baseline medication usage. Nevertheless, race is a social construct and not a physiologic concept and is an imprecise surrogate for genetic-related differences among subjects. Results of A-HeFT, therefore, will be clarified with continued genetic-based research, and clinicians should recognize the significant heterogeneity among prespecified groups, with perhaps greater genetic differences within than between certain racial or ethnic groups.

Combined treatment with ISDN and hydralazine has shown good tolerability. In V-HeFT I, discontinuation rates were identical for ISDN and hydralazine versus placebo (22% in both groups). The main adverse events leading to discontinuation of ISDN and hydralazine were headache (12%), dizziness (6%), gastrointestinal effects (4%), and nervous system effects (4%); 3 patients (2%) discontinued because of arthralgia and 3 because of possible lupus. Headache was the only adverse event observed more frequently with ISDN and hydralazine than with enalapril in V-HeFT II (73% vs 54% of patients, p <0.05). In A-HeFT, in which patients had been receiving standard HF therapy for 3 months, headache and dizziness were significantly more frequent in the ISDN plus hydralazine group, whereas exacerbations of congestive HF (both moderate and severe) were significantly more frequent in the placebo group. Potential adverse events associated with FD ISDN–hydralazine that may require specific attention include hypotension and lupus-like syndrome.

Isosorbide Dinitrate and Hydralazine in Heart Failure

Compared with placebo, treatment with ISDN and hydralazine reduced the relative risk of death by 36% after 3 years with minimal background therapy (digoxin and diuretics) in V-HeFT I. Furthermore, ISDN and hydralazine improved survival in black or African-American patients, although the effect was not significant in white patients ( Figure 2 ). In V-HeFT II, treatment with ISDN and hydralazine did not improve survival compared with enalapril, although the effects on all-cause mortality were equivalent to those of enalapril in black patients and inferior to enalapril in white patients.

These findings led to the design of an outcomes study with fixed-dose (FD) ISDN–hydralazine (BiDil; Arbor Pharmaceuticals, Inc, Atlanta, Georgia) in self-identified black patients. The African-American Heart Failure Trial (A-HeFT) enrolled 1,050 patients with New York Heart Association class III or IV HF receiving guideline-based care, including β blockers, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, and/or angiotensin II receptor blockers. The primary outcome of A-HeFT was a composite score of mortality, hospitalization, and quality of life (QOL), and the clear survival benefit of FD ISDN–hydralazine over placebo led to termination of the study after 3 years ( Figure 3 ). With a median follow-up period of 10 months, FD ISDN–hydralazine in combination with neurohormonal blockade reduced mortality by 43%. In addition, in A-HeFT, adding FD ISDN–hydralazine to standard therapy decreased the number of hospitalizations and reduced length of hospital stay compared with standard therapy alone. The relative risk of an HF-related hospitalization during the first 2 years of treatment was equal to placebo in V-HeFT I and to enalapril in V-HeFT II. In A-HeFT, improvements in functional parameters included EF, left ventricular (LV) remodeling, and significant reduction in B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP). Additionally, based on the Minnesota Living with Heart Failure questionnaire, patients in A-HeFT reported improved QOL with FD ISDN–hydralazine.

The first hospitalization for HF was a component of the primary composite score in A-HeFT. With a mean follow-up of 10 months (range 0 to 18), 130 patients (24.4%) in the placebo group and 85 (16.4%) in the FD ISDN–hydralazine group (p = 0.001) were hospitalized. Relative risk of first HF hospitalization was reduced by 39% with FD ISDN–hydralazine compared with placebo (hazard ratio 0.61, 95% confidence interval 0.46 to 0.80, p <0.001; Figure 4 ). The treatment effect appeared early, approximately 50 days after starting treatment, and remained significant throughout the study. A similar beneficial effect of FD ISDN–hydralazine was observed in all the subgroups analyzed, including age (< or >65 years), gender, ischemic HF etiology, baseline blood pressure (BP; systolic BP >126 mm Hg), presence of diabetes mellitus, history of chronic renal insufficiency, and baseline medication usage. Nevertheless, race is a social construct and not a physiologic concept and is an imprecise surrogate for genetic-related differences among subjects. Results of A-HeFT, therefore, will be clarified with continued genetic-based research, and clinicians should recognize the significant heterogeneity among prespecified groups, with perhaps greater genetic differences within than between certain racial or ethnic groups.

Combined treatment with ISDN and hydralazine has shown good tolerability. In V-HeFT I, discontinuation rates were identical for ISDN and hydralazine versus placebo (22% in both groups). The main adverse events leading to discontinuation of ISDN and hydralazine were headache (12%), dizziness (6%), gastrointestinal effects (4%), and nervous system effects (4%); 3 patients (2%) discontinued because of arthralgia and 3 because of possible lupus. Headache was the only adverse event observed more frequently with ISDN and hydralazine than with enalapril in V-HeFT II (73% vs 54% of patients, p <0.05). In A-HeFT, in which patients had been receiving standard HF therapy for 3 months, headache and dizziness were significantly more frequent in the ISDN plus hydralazine group, whereas exacerbations of congestive HF (both moderate and severe) were significantly more frequent in the placebo group. Potential adverse events associated with FD ISDN–hydralazine that may require specific attention include hypotension and lupus-like syndrome.

Isosorbide Dinitrate and Hydralazine: Individual Agents Versus Combination Product

Different ISDN and hydralazine preparations were used for V-HeFT I, V-HeFT II, and A-HeFT, and it has been postulated that differences in the efficacy results might be related to pharmacokinetic differences among the drug formulations. To evaluate the different formulations, a 3-arm bioequivalence study was conducted in 56 healthy volunteers who were slow acetylators. Subjects were randomized to receive a single oral dose (10 mg/37.5 mg) of ISDN tablet plus hydralazine capsule, ISDN tablet plus hydralazine tablet, or a FD ISDN–hydralazine tablet (10 mg/37.5 mg, which differs from the A-HeFT formulation 20-mg/37.5-mg tablet in current clinical use ). The maximum concentration (C max ) and area under the curve were similar for ISDN in all 3 arms. However, the hydralazine tablet produced a lower C max (28.2 ± 15.8 ng/ml) and area under the curve (23.3 ± 15.1 ng·h/ml) compared with the hydralazine capsule (65.9 ± 53.9 ng/ml; 32.6 ± 13.4 ng·h/ml) or the FD ISDN–hydralazine tablet (51.5 ± 54.3 ng/ml; 32.6 ± 18.5 ng·h/ml), indicating that the formulations are not bioequivalent. These pharmacokinetic differences could help explain differences in efficacy between V-HeFT I and V-HeFT II. However, as these are pharmacokinetic results from healthy volunteers and no head-to-head study comparing administration of ISDN and hydralazine as individual agents versus the FD ISDN–hydralazine tablet has been conducted, no firm conclusions can be drawn.

It has been assumed that generic ISDN and hydralazine are a less expensive alternative than FD ISDN–hydralazine without any disadvantages in terms of compliance. However, it is reasonable to consider the differences in the pharmacokinetics among the formulations when prescribing a treatment regimen. A once- or twice-daily combination might have both pharmacokinetic and compliance benefits compared with the current thrice-daily regimen.

Hypertension and HF in Patients of African Ancestry

There is compelling evidence that controlling hypertension is key to preventing and/or managing overall cardiovascular disease morbidity and mortality, including HF. Although epicardial coronary artery disease is the most common cause of HF in most large clinical trials (predominately in white patients), hypertension is the most common cause of HF in African-Americans. In native Africans, the relation between HF and hypertension was observed in The Sub-Saharan Africa Survey of Heart Failure, which enrolled >1,000 patients with acute HF from 9 African countries over a 3-year period: approximately 50% of the cases of acute HF were attributed to hypertension. Hypertension is often more severe in African-American patients than in whites, with earlier onset and greater average systolic and diastolic pressures. Accordingly, in the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults longitudinal study that evaluated 5,115 subjects from the United States, black participants were more likely to develop HF by 50 years of age than whites.

Patients with moderate or severe hypertension are 2 to 3 times more likely than those with normal BP to develop HF after 15 years, and patients with hypertension are more likely to have evidence of endothelial damage and dysfunction compared with those without hypertension. A recent study compared echocardiographic and hemodynamic findings between 187 African-American patients with hypertension and 132 normotensive African-Americans. Impaired flow-mediated dilation was found to be inversely related to BP (r = −0.40, p <0.0001), and a negative association between flow-mediated dilation and LV mass index (β = −0.26, p <0.01) was most marked in patients with concentric LV hypertrophy. Further evaluation with myocardial contrast echocardiography revealed abnormal myocardial flow reserve, consistent with microvascular dysfunction and subendocardial ischemia. These data support the progression from hypertension to HF in African-American patients. The earlier onset of hypertension and poorer BP control in many African-Americans may accelerate the onset of HF in blacks in the United States compared with whites and other patients with hypertension. However, the time lag between the development of hypertension and the onset of HF is still several decades in African-American patients.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree