Chapter 73 Urologic Surgery

Urologic Anatomy For The General Surgeon

It is essential for the general abdominal surgeon to be intimately familiar with genitourinary anatomy to complete standard general surgical procedures, avoid iatrogenic injury, and deal with abnormal anatomy.1 Examples of particular areas of risk or challenge include the renal vasculature in major vascular and retroperitoneal tumor surgery, ureteral mobilization and injury avoidance in complex colonic procedures, urethral and prostatic relationship to the rectum, and spermatic cord and scrotal contents in complex inguinal hernia surgery.

Groin, Genitalia, and Perineum

Inguinal anatomy is well known to all general surgeons. The relevant urologic issues in this anatomic region relate to the spermatic cord and male genitalia. The detailed anatomy of the scrotal contents is beyond the scope of this discussion; suffice it to say that the testis lies within a mesothelial envelope, the tunica vaginalis. The vascular and genital ductal structures leave the testis from the mediastinum in the posterosuperior portion and travel via the scrotal neck into the inguinal canal. The spermatic cord is invested by the internal spermatic fascia, derived from the transversalis fascia. The cremaster muscle is derived from the internal oblique. The external spermatic fascia, derived from the external oblique aponeurosis, joins the cord below the external ring. The cord is susceptible to injury during inguinal dissection for hernia repair, especially in redo cases, when it may be encased in fibrosis and injured without recognition. Significant injury to the cord may put the viability of the testis at risk, even though the testis is supported by three collateral blood supply sources—external spermatic artery from the external iliac, internal spermatic or gonadal artery from the aorta, and vasal artery from the internal iliac branches. The vas deferens itself may also be injured anywhere along its course, from the midscrotal level to the inguinal canal to its intrapelvic portion. When inguinal herniorrhaphy is performed, care must be taken to avoid excessive tightening at the internal ring level, because compression of the cord at this level can result in venous, lymphatic, or arterial obstruction. In addition, the common use of nonabsorbable mesh materials in hernia repair, whether performed through an open inguinal or laparoscopic approach, may result in fibrotic and inflammatory changes involving the vas deferens, which can cause late occlusion and potentially azoospermia and infertility. This phenomenon has been well-documented in the literature; patients in their reproductive years should be counseled about this risk of groin surgery.2

The evaluation of the acute scrotum requires a sophisticated knowledge of genital structure and normal anatomy, as well as extensive clinical experience, for accurate diagnosis. The epididymis is located posteriorly and slightly lateral position to the testis; distinguishing acute epididymitis or epididymo-orchitis from testicular torsion or trauma is a commonly encountered clinical challenge. Scrotal ultrasound may be a helpful adjunct to history and physical examination in the rapid assessment of patients,3 because it is critical to rule out testicular torsion promptly to avoid permanent ischemic injury.

Urologic Infectious Disease

Complicated Urinary Tract Infection

Complicated urinary infection occurs in the setting of underlying abnormalities of the physiology or anatomy of the genitourinary system or in the presence of an immunocompromised host.4 Patients who recently have been catheterized or have undergone hospitalization and/or urologic or nonurologic surgery also fall into the category of patients with complicated urinary infection, because they may be experiencing transient functional or anatomic problems or may have acquired a nosocomial infection by resistant or atypical organism. Certain specific infections of the genitourinary system may require the surgeon’s involvement in the operative or critical care support setting. Patients with relapsing infection— that is, recurrent infection with the same organism following standard treatment for which eradication should be expected—should undergo urologic evaluation to determine whether there is a complicating factor preventing the infection from fully responding to standard treatment (e.g., unrecognized obstructed kidney or ureter, chronic abscess, impaired bladder emptying, foreign body in the urinary tract, ischemic state, urinary fistula).

A patient who is sick enough to warrant hospitalization for a febrile urinary infection, particularly if there are lateralizing signs potentially indicative of an upper tract inflammatory process (e.g., flank pain, tenderness, swelling, erythema), should have upper tract imaging performed urgently (ultrasound or CT). This should be done to ensure there is no undrained infection in an obstructed upper tract. I teach our residents that “the sun should never set on the obstructed, infected urinary tract”; these patients may deteriorate rapidly, despite antibiotic therapy, hydration, and supportive care, if prompt drainage is not instituted.5 I have witnessed deaths that might have been preventable when a patient was hospitalized for presumed pyelonephritis, but without upper tract imaging, which would have demonstrated an obstructing ureteral calculus with proximal pyonephrosis.

In achieving retrograde ureteral stent insertion, the urologist may choose a double-J internalized stent or an externally draining open-ended catheter, which is typically tied to a Foley catheter with sutures, similar to the approach used when a ureteral catheter is placed prior to pelvic or retroperitoneal surgery to aid in ureteral identification. Internal stents have the advantage of being less prone to dislodgment, and may be more comfortable for longer indwelling times, but the externally draining catheter has the advantage of being available for continuous monitoring of urine output and irrigation if it becomes clogged with pus, debris, or blood clots. Externally draining ureteral catheters generally are not left in place for more than a few days at a time. With internal stents, it is important to document their presence and discuss with the patient and family, when they could be reasonably expected to comprehend and recall the discussion, the temporary nature of the stent and importance of follow-up and removal to avoid late encrustation, occlusion, infection, obstruction, and potential loss of kidney function.6 This is an important medicolegal issue in the critical care and trauma settings that has been the source of litigation.

Specific Complicated Genitourinary Infectious States

Emphysematous Infection and Infections in the Diabetic Patient

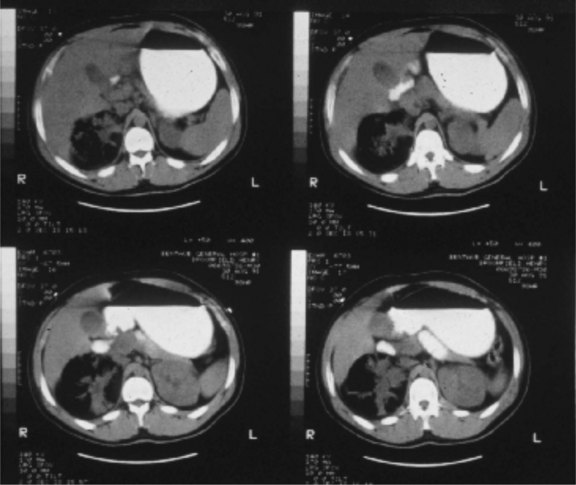

Gas-forming or emphysematous infection of the urinary tract is usually seen in the poorly controlled diabetic patient. Emphysematous pyelonephritis typically presents as a fulminant infection involving the renal parenchyma, which may progress to involve the perinephric space7 (Fig. 73-1). A lesser form of this process, emphysematous pyelitis, results in gas within the renal collecting system but not within the parenchyma. The causative agent most commonly is E. coli, which produces gas through a facultative anaerobic or fermentative process. Significant soft tissue destruction may result and a picture consistent with urosepsis is common. Control of the metabolic abnormalities and aggressive antibiotic and supportive therapy in a critical care setting are essential. If there is upper tract obstruction present, it should be relieved promptly with retrograde or antegrade tube drainage. If discrete purulent collections are present based on computed tomography (CT) imaging, percutaneous drainage may be attempted while the sepsis is being controlled medically. These patients often require urgent nephrectomy, although if the overall clinical status is improving with medical treatment, there may be an advantage to delaying surgical intervention until the patient is more stable. At times, the process may be focal or segmental and may respond solely to medical therapy and indicated drainage procedures.

Acute papillary necrosis is also most commonly seen in the diabetic patient.8 Often, there is an underlying ischemic state involving the renal papillae, which progresses to frank necrosis and passage of the sloughed papilla into the collecting system and ureter, causing obstruction and, if concomitant infection is present, often progresses to urosepsis. These patients require urgent drainage of the obstructed upper tract and, after their infection is resolved, endoscopic evacuation of the necrotic tissue. This process may present as a fulminant infectious illness or as a chronically progressive process.

Xanthogranulomatous Pyelonephritis

Xanthogranulomatous pyelonephritis (XGP) is a specific clinical and histologic entity that involves the presence of a foamy, lipid-laden, macrophage infiltrate in the renal parenchyma, with extensive inflammation, fibrosis, and loss of function. It is thought to result from chronic bacterial infection, usually in the presence of stones and chronic obstruction.9 The kidney is typically nonfunctional or poorly functioning and may be a source of chronic disease, pain, persistent infection, and sometimes fistulization to the flank or adjacent organs. Nephrectomy is usually indicated. Radiographically, by CT, there may be an apparent collecting system dilation; however, drainage attempts often are unproductive because the material is often solid or too viscous to drain. Patients may present with active infection and require a cooling off period with antibiotics and supportive care to be readied for surgery. The general surgeon may become involved in such cases because of this lesion’s propensity to become densely adherent to surrounding structures, particularly the diaphragm, pancreas, duodenum, great vessels, iliac vessels, and flank wall. The risk of iatrogenic adjacent organ injury is high in these nephrectomies. Often, the renal hilum is so inflamed and fibrotic that the renal vessels cannot be individually dissected; in these cases, placement of a vascular pedicle clamp with renal excision and oversewing the pedicle is necessary.

Epididymitis, Epididymo-Orchitis, Without and With abscess

The topic of the acute scrotum is important to urologists and general surgeons because the differential diagnosis can be challenging and an accurate diagnosis may only be achievable surgically.10 The epididymis, located posterolateral to the testis, becomes infected through ascending infection from the urinary tract down the vas deferens into the scrotum. When infection is advanced, the entire scrotal contents ipsilaterally become involved, with overlying skin fixation and edema. It may be difficult to distinguish this entity from late torsion, incarcerated inguinal hernia, or testicular tumor with necrosis and inflammation. Scrotal ultrasound is useful diagnostically, especially to rule out associated abscess. Cultures should be obtained and patients should be treated with broad-spectrum antibiotics. If abscess is present, surgical drainage and often orchiectomy is indicated. If improvement is seen with medical therapy, rest, and scrotal elevation, continued observation may result in eventual, although often slow, resolution with medical therapy alone. If there is persistent pain and mass, or signs of testicular ischemia are noted by repeat Doppler imaging, exploration and orchiectomy may still be necessary to resolve the process.

Fournier’s Gangrene

Gas-forming and necrotizing soft tissue infections are covered in detail elsewhere in this text. When the genitalia are involved, patients typically present with significant pain and tenderness, scrotal and genital swelling, discoloration or frank necrosis, crepitus and, at times, foul-smelling discharge (Fig. 73-2). Bacteriologically, these infections are usually polymicrobial, with aerobes, anaerobes, gram-positive, and gram-negative organisms. Necrotizing soft tissue infections of the genitalia, as in other anatomic regions, require aggressive broad-spectrum antibiotic treatment, supportive care, and urgent surgical drainage with aggressive débridement of the necrotic tissue.11 The magnitude of the débridement depends entirely on the degree of progression of the process. It is rare for the process to involve the testicles or deep tissues of the penis, so these structures should be preserved, if possible. I prefer to separate the parietal tunica vaginalis of the testes from the overlying necrotic dartos and skin and preserve the tunical compartment intact, which helps with wound care and patient comfort. If the penile skin is necrotic, it can be débrided down to but not through the Buck’s fascial layer. It is uncommon for the urethra to be involved although, occasionally, a defined urinary tract source may be evident, such as a urethral stricture with perforation and local infection. Suprapubic tube diversion is generally not necessary; urethral catheter drainage is generally sufficient. Wound vacuum-assisted closure (VAC) device placement after purulence has resolved results in rapid wound size reduction and fluid evacuation. Grafting large defects with meshed split-thickness grafts for the scrotum and nonmeshed thick split-thickness grafts for the penile shaft yields favorable results.

Genitourinary Fungal and Tuberculous Infections

Fungal infections of the urinary tract are most often seen in diabetics, immunocompromised patients, and those who have had extensive nosocomial and antibiotic exposure. These infections vary markedly, from superficial candidal infections of the groins and genitalia, treatable with standard topical agents, to invasive fungal infections of the bladder or kidneys that may cause urosepsis and be life-threatening.12 Fungal infections are addressed in general terms elsewhere in this text. Specific issues related to the urinary tract include the occasional need for antifungal bladder irrigation, potential for fungal deposits (fungus balls) forming in the renal colleting system requiring direct irrigation or occasionally endoscopic removal, and complex cutaneous involvement of the genitalia. Infectious disease consultation and support are valuable in such cases because the organisms may be resistant and atypical, and selection of treatment agents may not be straightforward.

Genitourinary (GU) tuberculosis may be manifested as an isolated GU infection (e.g., tuberculous cystitis, epididymitis) or as part of a systemic infection.13 Urine cultures from the first morning void are most effective in detecting infection. Current references should be consulted to address specific anti-infective therapy agent selection. Upper urinary tract tuberculosis infection may cause ureteral strictures, which may progress even with therapy and result in silent obstruction and renal loss if not promptly detected. These patients should be regularly monitored by ultrasound to assure adequate upper tract drainage. Tuberculous epididymitis should be suspected if chronic epididymitis results in cutaneous fistula formation; following adequate medical therapy, epididymectomy or orchiectomy may be indicated for residual mass, pain, or fistula. Renal nonfunction following diagnosis and treatment may occasionally require partial or total nephrectomy. As a general principle, atypical infections of the genitourinary system should prompt testing for an immunocompromised state, including testing for HIV status, because varied urologic manifestations of such viral infections may be observed.14

Voiding Dysfunction, Bladder Outlet Obstruction, Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia, And Incontinence

Urinary Incontinence

Urge incontinence is most commonly caused by overactive bladder or detrusor instability. This may be age-related, caused by a specific anatomic bladder irritative focus, or be neurologic in origin. Urologic consultation may be necessary to determine the cause; anticholinergic or antimuscarinic medication therapy is the mainstay of treatment once critical underlying issues (e.g., bladder tumor, carcinoma in situ, obstruction) are excluded. There is a burgeoning variety of overactive bladder medications on the market. They generally have predictable side effects, including dry mouth, constipation, and often confusion in older adults, and should be avoided in patients with a history of narrow-angle glaucoma; an ophthalmologist’s approval should be sought for these patients. These drugs will decrease urgency and episodes of urge incontinence in most patients and are typically safe for long-term use. Refractory cases may require more complex interventions, including nerve stimulator devices, intravesical botulinum toxin injections and, rarely, surgical bladder augmentation.15

It is common for incontinence to be mixed—that is, to have elements of stress and urgency. Urodynamic testing is important in such cases to distinguish obstruction from detrusor dysfunction and to plan therapy.16 In general, the medical component (e.g., bladder control medicine for urgency) is treated first, with surgical intervention reserved for patients in whom medical management is not effective or does not address a critical underlying problem, such as high-grade outlet obstruction.

Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia and Bladder Outlet and Urethral Obstruction

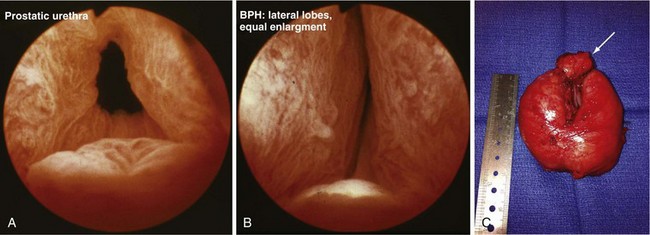

BPH may result in LUTS (lower urinary tract symptoms) and BOO (bladder outlet obstruction). The process involves hypertrophy and hyperplasia, with increased glandular and stromal elements of the prostate in varying amounts. There is little correlation between the measured volume of the prostate and degree of symptomatology that results. In addition, the degree of BOO does not necessarily correlate with the severity of LUTS. Symptoms may be mild and manageable just with watchful waiting, or may be more significant, requiring long-term medical therapy and, at times, surgical intervention. Complications of BPH may include bladder damage and loss of function from chronic distention, upper tract deterioration, troublesome hematuria, bladder stone formation, and recurrent urinary infection. Practice guidelines for BPH have been produced by the American Urologic Association to guide providers in the diagnosis and management of BPH.17 The basic evaluation involves history and physical examination, digital rectal examination, urinalysis, prostate-specific antigen (PSA) level testing (in select patients), other interventions to rule out prostate cancer and, at times, other tests to rule out other significant urologic pathology (e.g., urine cytology, upper tract imaging, cystoscopy). A quantitative symptom score may be useful. Checking PVR urine volume may be valuable as well. After the basic assessment, patients are directed toward some therapeutic approach, such as watchful waiting, medical therapy, or minimally invasive or standard surgical intervention. The management selection reflects patient preferences and the presence of complicating factors.

When medical therapy is ineffective and symptoms remain bothersome, or when there is an objective surgical indication (e.g., severe obstruction based on urodynamic data, recurrent hematuria or infection, urinary tract anatomic deterioration from obstruction), surgical intervention is considered. The standard approaches include minimally invasive options (e.g., laser procedures, thermotherapy, microwave procedure), TURP or, when the adenomatous growth is particularly large, open simple prostatectomy to enucleate the adenoma surgically (Fig. 73-3). Complications of these surgical procedures include persistent bleeding, prostatic capsular perforation, or perforation into periprostatic venous sinuses, with fluid absorption, which may result in hyponatremia because of the glycine irrigation typically used (newer electroresection systems use normal saline with a bipolar electrode, eliminating the hyponatremia risk) and, rarely, injury of an adjacent structure (e.g., rectal injury with TURP or open prostatectomy).

Male Reproductive And Sexual Dysfunction

An area of practice to which urologists devote significant attention is male infertility and sexual dysfunction.18 Diagnostic evaluation, medical treatment, and surgical therapy represent sophisticated aspects of urologic care; general surgeons should have a basic familiarity with the management of these disorders. They may at times be called on to participate in the treatment of surgical complications of genital surgery and prosthetic implant surgery; the patient’s history of having undergone these procedures may affect the precautions and challenges of nonurologic pelvic and groin procedures.

Male Infertility: Evaluation and Treatment

The standard male factor evaluation involves a detailed history, physical examination, and basic laboratory and imaging evaluation. The history should include a discussion regarding sexual and reproductive history, including potential gonadotoxic exposure, urologic and sexually transmitted infections, trauma and prior surgery involving the pelvis, groin, and genitalia, and family history of infertility. Physical assessment should include a general evaluation of masculinization, genital findings, including normal meatal location, testicular size and, consistently, presence and normalcy of the epididymis and vas deferens, and possible presence of a varicocele (Fig. 73-4). Perineal and rectal examinations are routine parts of this assessment.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree