Upper-extremity Effort-induced Thrombosis

John K. Karwowski

Cornelius Olcott IV

There are two categories of subclavian vein thrombosis (SVT). One, effort-induced thrombosis, which is covered in this chapter, is also known as primary SVT or Paget-von Schrotter syndrome. This form occurs in young, active men and women who are otherwise healthy. Secondary SVT includes those cases that result from radiation, trauma, cannulation, or manipulation, such as occurs with large central vein catheters and pacemaker wires. Although there is no consensus as to the optimum management for primary SVT, there is no question that left untreated, symptomatic patients will suffer chronic disability secondary to venous obstruction. In addition, there is a small but definite incidence (10% to 15%) of pulmonary emboli in untreated cases of effort-induced thrombosis.

We believe the best management for patients with effort-induced SVT involves a multidisciplinary approach that includes venography, catheter-directed thrombolytic therapy, anticoagulation, thoracic outlet decompression when indicated, and occasional venous angioplasty.

Diagnostic Considerations and Nonoperative Management

Primary SVT typically occurs in young, active men and women. The average age in our series was 29. It is frequently associated with repetitive use of the arm, which occurs, for example, in baseball pitchers and weight lifters or people who carry heavy backpacks or shoulder bags, which may increase compression of the subclavian vein. SVT is the leading vascular disorder in professional and amateur athletes.

Patients with SVT characteristically present with sudden onset of arm swelling, pain, and cyanotic discoloration. Arterial examination is normal. The diagnosis is confirmed by duplex ultrasound.

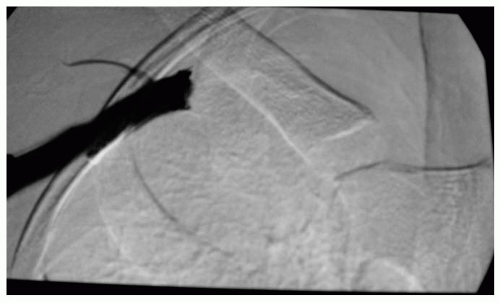

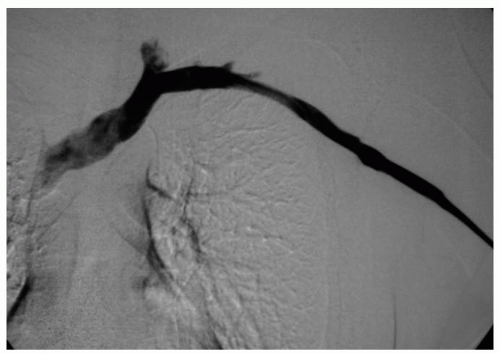

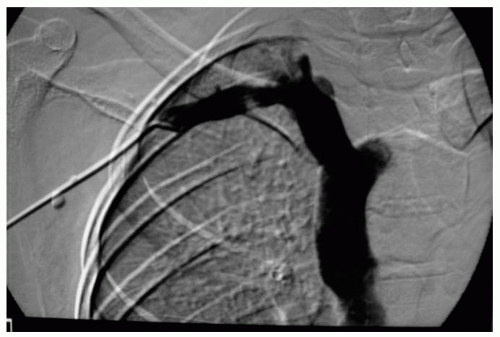

Patients with a positive ultrasound should undergo prompt venography to ascertain the extent of obstruction and the status of collaterals. Venograms should be performed in both the neutral position and with the involved arm in abduction and external rotation (Figs. 70-1, 70-2, and 70-3). The latter view demonstrates the extent of compression of the subclavian vein and the collateral veins. It is our practice to initiate lytic therapy at the time of venography if it is positive. The benefit of lytic therapy is twofold. First, it removes the thrombus from the vein and thereby improves venous return from the arm. Second, after the clot is removed, venography gives a better idea of the actual site of obstruction and the extent of external compression on the subclavian vein and its collaterals.

Most authors agree that the sooner lytic therapy is initiated, the greater the chance for success. However, in our series some patients did benefit from thrombolytic therapy even with delays of up to 1 month. Hence, we are aggressive about using lytic therapy even in those cases where there has been a delay in getting to us for treatment. Lytic agents that we have used include urokinase, tPA, and TNK. The lytic agent is infused via a multisidehole catheter directly into the area of thrombosis. Infusion is continued for 24 to 72 hours. Heparin is administered simultaneously to prevent clotting around the catheter. Success of thrombolysis is assessed by serial venograms performed every 12 to 24 hours. Thrombolysis is discontinued when one or more of the following conditions are met:

No interval change in the appearance of the vein on two sequential venograms

Bleeding complications occur

Evidence of disseminated intravascular coagulopathy or systemic fibrinolysis

72 hours of continuous infusion completed

In addition to chemical thrombolysis, mechanical thrombolysis may be of value. There are several mechanical devices in

various stages of development, and some are already on the market. Even though our experience is small, we believe there may be a role for these devices in those patients that do not respond adequately to thrombolytic agents or who have a contraindication to chemical thrombolysis.

various stages of development, and some are already on the market. Even though our experience is small, we believe there may be a role for these devices in those patients that do not respond adequately to thrombolytic agents or who have a contraindication to chemical thrombolysis.

Figure 70-3. Same patient as in Figure 70-2 with arm abducted. Note significant compression of subclavian vein at the thoracic outlet. |

As discussed above, we believe positional venography should be repeated after maximum clot lysis to better demonstrate the pathology, e.g., site and extent of obstruction and the status of collaterals, as well as the extent of extrinsic compression of the subclavian vein and its collaterals (Figs. 70-4 and 70-5). Once the clot is cleared, it is much easier to determine the cause of the original thrombosis. In cases of primary SVT, the obstruction is at the thoracic outlet (Figs. 70-1 and 70-3).

The differential diagnosis of effort-induced SVT includes: secondary SVT, thrombosis/obstruction of a more proximal vein (e.g., by tumor), lymphedema, and trauma.

Pathogenesis

Primary SVT occurs in a vein that is injured as a result of repetitive strenuous activity in a patient with anatomic abnormalities that predispose the vein to extrinsic compression in the costoclavicular space. This repetitive injury leads to thickening and stenosis of the vein, which, if unrecognized, may eventually lead to sudden and complete thrombosis of the subclavian vein and its collaterals. The structures that can compress the subclavian vein include the first rib, the clavicle, the anterior scalene and subclavius muscles, and abnormal fibrous bands and scarring.

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|