Daniel J. Lenihan, Syed Wamique Yusuf

Tumors Affecting the Cardiovascular System

Cardiac masses frequently present significant diagnostic and therapeutic clinical challenges. In many cases a cardiac mass is detected as an incidental finding and the resultant evaluation may culminate in confirmation of a cardiac tumor; however, this is generally an uncommon event because other cardiac masses, such as thrombus or vegetation, are generally much more common. This chapter begins by describing the initial symptoms and signs that may indicate a cardiac tumor, followed by an explanation of a typical evaluation process that depends heavily on current sophisticated imaging techniques. Once a cardiac tumor is suspected, the ultimate diagnosis is usually confirmed by biopsy or surgery because histologic diagnosis has a direct bearing on further treatment planning. The remainder of the chapter then focuses on delineation and potential management of cardiac tumors and the overall anticipated outcomes. It should be pointed out that this is an inexact science because of the relatively rare occurrence of cardiac tumors. Furthermore, the final pathologic diagnosis is typically confirmed after the bulk of decisions regarding treatment were made in advance of obtaining the final diagnosis.

Clinical Manifestations of Cardiac Tumors

Initial Decision Making

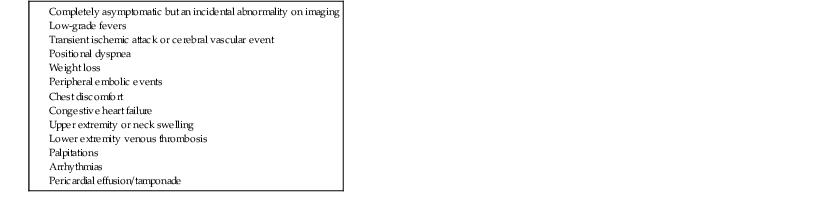

It is interesting to note that patients with cardiac tumors may initially have no symptoms or physical findings but exhibit abnormalities on imaging. Alternatively, there may be a host of nonspecific symptoms or findings on physical examination, and of course, there may be very specific and detailed symptoms or signs that should alert physicians to the possibility of a cardiac tumor (Table 85-1). The most important consideration in confirming the presence of a cardiac tumor is a high index of suspicion and integration of the symptoms, findings on physical examination, and imaging characteristics in a logical way to establish a clinically reasonable plan of action.

TABLE 85-1

Range of Clinical Findings That May Indicate a Cardiac Tumor

The initial evaluation is typically an imaging test such as two-dimensional echocardiography1 or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)2,3 in which a mass is identified. Depending on the characteristics of this mass and the known comorbid conditions of the patient, additional imaging may be undertaken, including three-dimensional echocardiography with contrast enhancement,4 MRI with gadolinium,5,6 coronary angiography to define the presence of coronary artery disease,7 position emission tomography (PET) to provide staging for cancer,7 or computed tomography (CT) to clarify intrathoracic structures.8,9 Transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) can also provide very specific anatomic information that is critical to planning treatment (Table 85-2).7

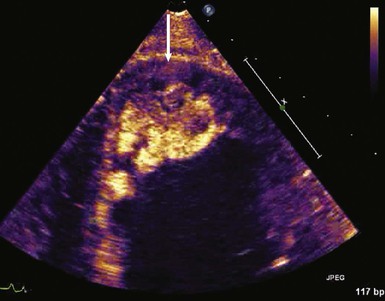

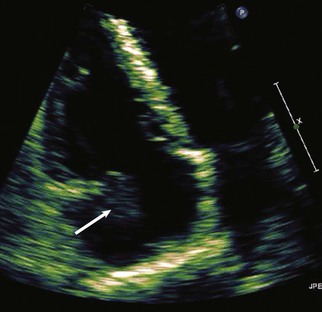

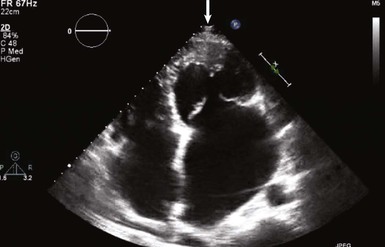

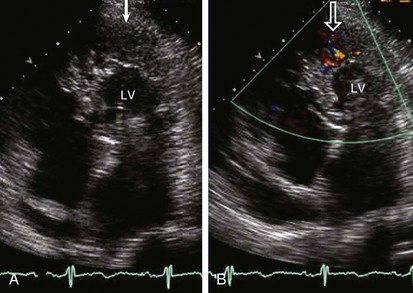

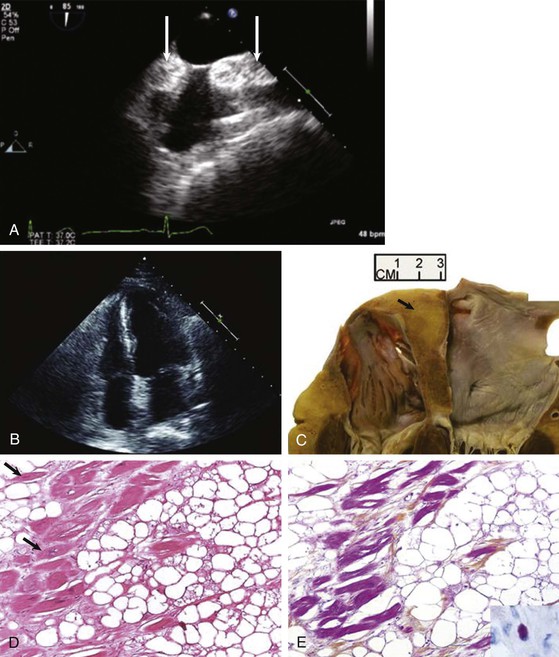

When assessing a cardiac mass as initial evaluation for a cardiac tumor, the clinical context in which the image was obtained is critical because the differential diagnosis of a cardiac mass is broad and includes tumors, thrombi, infection, and artifacts (Table 85-3). For example, if two-dimensional echocardiography shows an apical mass in a patient with new-onset heart failure, a cardiac tumor is less likely.10 The presence of a severe wall motion abnormality, as well as the fact that the mass may appear distinct from the myocardial wall and is lobulated, strongly suggests that the mass is much more likely to be a thrombus than a tumor (Fig. 85-1). Another scenario involves a patient with a history of melanoma that is metastatic to other organs and on routine cardiac imaging a solid mass is seen in an unusual location. Because there is no wall motion abnormality and no significant valvular disease or clinical signs suggestive of infective endocarditis, this mass is very likely to be a metastatic lesion to the heart (Fig. 85-2). A common consideration that may suggest a tumor, in regard to imaging, is movement of the mass and related structures during a motion image. If a tumor is infiltrating the myocardium, the involved myocardial area will not contract in normal fashion. A left ventricular myocardial apical mass contracting similar to that of surrounding tissue is likely to be either focal hypertrophy (Fig. 85-3) or left ventricular noncompaction11,12 (Fig. 85-4) as opposed to a cardiac tumor (Fig. 85-5). Furthermore, progression of an image over time may also indicate the pathologic process. If a cardiac mass changes in size from one image to the next, suspicion of a cardiac tumor is much higher. However, if an apical mass is stable for months or years, it is very unlikely to be a cardiac tumor. Of course, the exact nature and location of a mass are critical in determining whether it is likely to be a tumor.13 A classic example of this principle is lipomatous hypertrophy of the intra-atrial septum (Fig. 85-6A, B). The initial suspicion might be a myxoma or other tumor, but TEE revealing specific characteristics that are a hallmark of lipomatous hypertrophy will confirm the diagnosis.14

Classification of Cardiac Tumors

Cardiac tumors are divided into primary and secondary tumors. Primary cardiac tumors are very rare, with an autopsy incidence of 0.001% to 0.03%,15 and include benign or malignant neoplasms that may arise from any tissue of the heart. Secondary, or metastatic, cardiac tumors are 30 times more common than primary neoplasms, with an autopsy incidence of 1.7% to 14%.16 Table 85-4 summarizes some of the pathologic descriptions of cardiac tumors that have been reported but is not an exhaustive list in that there have been many very specific pathologic descriptions reported and it can be difficult to adequately categorize them. Thus general categories will be discussed in the remainder of this chapter.

Benign Primary Cardiac Tumors

Most (>80%) primary cardiac tumors are benign, and myxoma is by far the most common.15,17 Myxoma constitutes about 50% of all benign cardiac tumors in adults, but only a small percentage of such tumors in children.18 Rhabdomyoma is the most common benign tumor in children and accounts for 40% to 60% of cases.17 Other benign cardiac tumors that have been described include fibromas, lipomas, hemangiomas, papillary fibroelastomas, cystic tumors of the atrioventricular node, and paragangliomas. The remaining 20% of primary cardiac tumors are malignant and usually described pathologically as sarcomas.19–21

Common Clinical Manifestations

Patients are commonly asymptomatic and the tumor is found as an incidental finding on two-dimensional echocardiography. When symptoms are present, dyspnea, especially dyspnea that is worse while lying on the left side, should alert an astute clinician to the possibility of a myxoma. Most signs and symptoms related to myxoma result from obstruction of the mitral valve (syncope, dyspnea, and pulmonary edema), followed by embolic manifestations.20 Patients may also have nonspecific symptoms such as fatigue, cough, low-grade fever, arthralgia, myalgia, weight loss, and erythematous rash, as well as laboratory findings of anemia, increased erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and increased C-reactive protein and gamma globulin levels. Less commonly they may have thrombocytopenia, clubbing, cyanosis, or the Raynaud phenomenon. Findings on physical examination can reveal a systolic murmur or a diastolic murmur suggestive of mitral stenosis. A tumor plop may also be present (a low-pitched diastolic sound heard as the tumor prolapses into the left ventricle).20 In one study a cardiac auscultation abnormality was detected in 64% of the patients22; the most common abnormal auscultation findings are a systolic murmur (in 50% of cases), followed by a loud first heart sound, an opening snap, and a diastolic murmur. A systolic murmur may be caused by damage to the valves, failure of the leaflets to coapt, or narrowing of the outflow tract by the tumor. A diastolic murmur is due to obstruction of the mitral valve by the myxoma. Tumor plop may be confused with a mitral opening snap or a third heart sound and can be detected in up to 15% of cases.22 Chest examination may reveal fine crepitations consistent with pulmonary edema. Examination of the extremities may also reveal signs of an embolic phenomenon. The signs vary depending on the vascular territory involved. Involvement of the cerebral vessels results in neurologic signs, involvement of the coronary arteries may result in an acute coronary syndrome, intestinal arterial obstruction may result in an ischemic bowel, and peripheral arterial obstruction can result in limb-threatening ischemia.

Useful Investigations

Abnormal results on laboratory tests that can be useful may include anemia, elevated serum gamma globulin, elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and increased serum C-reactive protein. No electrocardiographic (ECG) findings are specific for myxoma. Chest radiographic findings are also nonspecific but include signs of congestive heart failure, cardiomegaly, and left atrial enlargement. In some cases the tumor itself may be visible because of calcification.22 Two-dimensional echocardiography should usually demonstrate a mass in the atrium with the stalk attached to the intra-atrial septum (see Fig. 85-8). TEE provides specific delineation of the tumor, including its size and origin. CT and MRI provide better delineation of the intracardiac mass, the extent of tumor in relation to extracardiac structures, and anatomic definition for preoperative planning.

Myxomas

Most myxomas (>80%) are found in the left atrium and in decreasing frequencies in the right atrium, right ventricle, and left ventricle. The incidence of cardiac myxoma peaks at 40 to 60 years of age, with a female-to-male ratio of approximately 3:1.20 Most myxomas occur sporadically but may be familial, and occasionally they have been described in relation to a particular syndrome called the Carney complex, an autosomal dominant condition associated with cardiac myxomas, myxomas in other regions (cutaneous or mammary), hyperpigmented skin lesions, hyperactivity of the adrenal or testicular glands, and pituitary tumors. The Carney complex occurs at a younger age and should be considered when cardiac myxomas are discovered in atypical locations in the heart.19

Cause and Pathophysiology

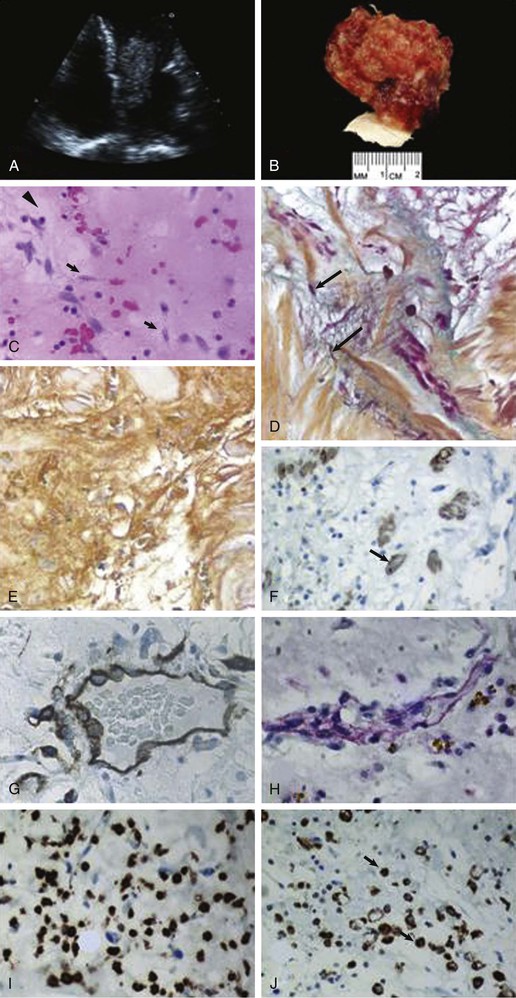

The exact origin of myxoma cells remains uncertain, but they are thought to arise from remnants of subendocardial cells or from multipotential mesenchymal cells in the region of the fossa ovalis that can differentiate along a variety of cell lines. The hypothesis is that cardiac myxoma originates from a pluripotential stem cell and the myxoma cells express a variety of antigens and other endothelial markers. Myxomas typically form a pedunculated mass with a short broad base (85% of myxomas), but sessile forms can also occur.15 Classically, myxomas appear yellowish, white, or brownish and are frequently covered with thrombus (Fig. 85-7). Tumor size can range from 1 cm to larger than 10 cm, and the surface is smooth in most cases (Figs. 85-8 and 85-9). Myxomas may have a surface that consists of multiple fine or very fine villous, gelatinous, and fragile extensions that have a tendency to fragment.15 Histologically, myxomas are composed of spindle- and stellate-shaped cells with myxoid stroma that may also contain endothelial cells, smooth muscle cells, and other elements surrounded by an acid mucopolysaccharide substance. Calcifications may also be seen in some cases.15

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree