Tuberculosis

GENERAL PRINCIPLES

Classification

• Active infection can occur with initial exposure to Mycobacterium tuberculosis (MTB) or following reactivation of latent disease.

• Latent infection occurs when the body has suppressed the primary infection but failed to eradicate the mycobacteria, which find an intracellular reservoir within macrophages.

Epidemiology

• Approximately one-third of the world’s population is estimated to carry MTB.1 Most infections are latent. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), highest incidence regions (sub-Saharan Africa, India, Southeast Asia, and Micronesia) have rates from 100/100,000 to over 500/100,000. Worldwide in 2014 there were 9.6 million new cases of TB and 1.5 million TB deaths. HIV patients accounted for 13% of new cases and 27% of deaths.2

• In the United States, 9421 cases (2.96 per 100,000 incidence rate) were reported to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in 2014.1 Two-thirds of these cases occurred in non–US-born individuals.

• Incidence temporarily surged in the early 1990s with the spread of HIV/AIDS and increased immigration from endemic areas but has since been decreasing.3

• Globally, it is estimated that 5% of TB cases in 2014 (about 480,000 cases) were caused by multidrug-resistant (MDR) organisms.4

• In 2013, 1.3% of US cases were MDR-TB.5

Pathophysiology

• Infection is transmitted by deposition of small airborne particles (<5 microns in diameter) containing MTB in an alveolus. Approximately 5% of exposed patients develop primary infection, which is usually self-limited.

Local inflammation forms caseating granulomas with lymphadenopathy.

Local inflammation forms caseating granulomas with lymphadenopathy.

In immunocompromised hosts, hematogenous spread can cause diffuse extrapulmonary disease.

In immunocompromised hosts, hematogenous spread can cause diffuse extrapulmonary disease.

• In a small group of patients, rupture of a subpleural caseous focus causes pleuritis.

Tuberculous proteins trigger a delayed hypersensitivity reaction.

Tuberculous proteins trigger a delayed hypersensitivity reaction.

Pleural fluid cultures are commonly negative.

Pleural fluid cultures are commonly negative.

An untreated, isolated tuberculous effusion typically resolves spontaneously but patients are at higher risk for developing reactivation TB within the next 2 years.

An untreated, isolated tuberculous effusion typically resolves spontaneously but patients are at higher risk for developing reactivation TB within the next 2 years.

• Following primary infection, 5–10% of immunocompetent individuals experience reactivation of disease. Immunocompromised state, drug use, and medical comorbidities increase risk of reactivation.6

Risk Factors

• The most important risk factor is exposure to MTB. Exposure risks include close contacts of those with active infection, foreign-born persons from endemic areas, residents of high-risk congregate settings (such as correctional facilities and homeless shelters), healthcare workers caring for high-risk patients, and illicit drug abusers.6

• Patients with HIV infection, other immunocompromised states (including tumor necrosis factor-α inhibitor use, glucocorticoid use, and posttransplant status), chronic medical illnesses (e.g., diabetes mellitus, silicosis, and chronic kidney disease requiring dialysis), alcoholism, malnutrition, and findings on CXR to suggest previously cleared disease (e.g., granulomas, apical fibronodular changes) are at increased risk for developing active disease once exposed.7,8

• A 2007 metaanalysis suggested that exposure to tobacco smoke is also a modest risk factor.9

Prevention

• Inpatients with suspected pulmonary TB should be placed in negative-pressure isolation until ruled out for disease.

• Patients with exclusively extrapulmonary disease are not contagious. These patients do not need to be placed on airborne precautions unless immunocompromised, in which case they should likewise be ruled out for concurrent active pulmonary TB.

DIAGNOSIS

Clinical Presentation

• Primary infection typically takes the form of a self-limited respiratory illness.

The most common symptoms are chest pain and subacute, low-grade fever.

The most common symptoms are chest pain and subacute, low-grade fever.

Pleuritic pain may represent a tuberculous effusion.

Pleuritic pain may represent a tuberculous effusion.

• Reactivation can have a variable and unimpressive presentation.

The most common history involves productive cough, fatigue, and weight loss for at least 2–3 months.

The most common history involves productive cough, fatigue, and weight loss for at least 2–3 months.

Fever, night sweats, dyspnea, chest pain, and hemoptysis are classic but are each present in less than one-third of patients.

Fever, night sweats, dyspnea, chest pain, and hemoptysis are classic but are each present in less than one-third of patients.

• Chest findings are variable and depend on the nature of disease.

Alveolar infiltrates may manifest as rales.

Alveolar infiltrates may manifest as rales.

Tubular breath sounds may be audible over areas of complete consolidation.

Tubular breath sounds may be audible over areas of complete consolidation.

Dullness to percussion may indicate pleural thickening or effusion.

Dullness to percussion may indicate pleural thickening or effusion.

Breath sounds may be soft or hollow (amphoric) locally over cavities.

Breath sounds may be soft or hollow (amphoric) locally over cavities.

• Examination of the extremities may reveal digital clubbing.

Differential Diagnosis

• TB should be suspected in any individual presenting with cough for >2 weeks and (a) classic symptoms, (b) risk factors for exposure, or (c) immunocompromise.

• High-risk patients with abnormalities on imaging should provide sputum for evaluation even when asymptomatic.

• Consider TB in patients who fail treatment for community-acquired pneumonia (CAP).

• Other relatively common differential diagnostic items for pulmonary TB include fungal infections (see Chapter 15), nontuberculous mycobacterial infections (e.g., M. avium complex, M. kansasii), lung abscess/septic emboli, sarcoidosis, and cancer.

Diagnostic Testing

Tuberculin Skin Test

• The tuberculin skin test (TST) is used to diagnose latent TB infection (LTBI).

• Patients at risk of exposure and those at risk for developing TB if exposed should be tested. Individuals without these risk factors should not be routinely tested because a positive TST is less likely to represent true LTBI. The decision to test implies a de facto decision to treat if the test is positive.

• TST involves intradermal injection of a standardized dose of 5 tuberculin units purified protein derivative. The injected material forms a 5–10-mm wheal immediately.

• The reaction to the TB proteins should be measured 48–72 hours later.

• The area of induration, not erythema, determines a positive or negative test.

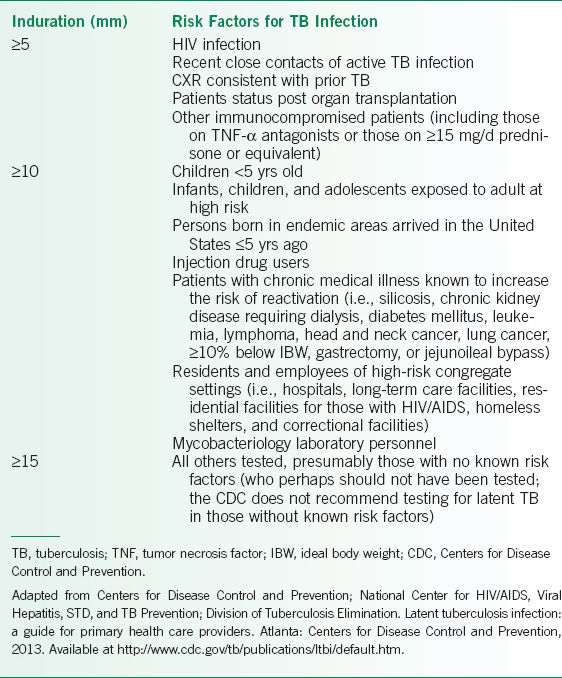

• Interpretation of the skin test is stratified by level of risk (Table 14-1).10,11 Positive tests are defined as:

An area of induration with diameter ≥5 mm in those at highest risk of developing active infection—persons with HIV, immunocompromise, close contact with active TB, or radiographic findings consistent with prior TB.

An area of induration with diameter ≥5 mm in those at highest risk of developing active infection—persons with HIV, immunocompromise, close contact with active TB, or radiographic findings consistent with prior TB.

A reaction ≥10 mm in those at risk of exposure—persons born in endemic areas, injection drug users, healthcare workers, and residents of congregate settings—and those with chronic medical conditions that place them at intermediate risk of progression to active disease, such as diabetes mellitus, renal failure, or silicosis.

A reaction ≥10 mm in those at risk of exposure—persons born in endemic areas, injection drug users, healthcare workers, and residents of congregate settings—and those with chronic medical conditions that place them at intermediate risk of progression to active disease, such as diabetes mellitus, renal failure, or silicosis.

A reaction ≥15 mm for persons without risk factors. In general, the CDC does not recommend screening such individuals, however, administrative constraints sometimes required such testing.

A reaction ≥15 mm for persons without risk factors. In general, the CDC does not recommend screening such individuals, however, administrative constraints sometimes required such testing.

• A positive TST should be followed by CXR. Symptoms or radiographic findings suggestive of active TB should prompt attempts to isolate the organism as described above. If cultures and Gram stain of sputum samples are negative, LTBI is present.

• A false-positive TST can occur when the test is repeated within 1 month of a previous TST in the absence of a new exposure. This so-called booster reaction is due to immunologic stimulation by the first test in those with remote exposure. It should not be interpreted as a new conversion. Two-step testing is recommended only in persons who will be tested periodically, typically healthcare workers at the time of hiring. If either the first or second test (1–3 weeks later) is positive the individual is considered previously infected (i.e., prior to the current employment) and treated appropriately for latent TB.11

• Patients with history of bacille Calmette–Guérin (BCG) vaccination may have a false-positive TST. However, due to the variability of the host response to BCG and the inconsistency of its protection against MTB, these patients should be treated as if the test were positive.11

• False-positive TST may occur with nontuberculous mycobacteria.

• An increase in size of tuberculin reaction >10 mm in the setting of new or ongoing exposure represents conversion.

• Falsely negative TSTs may occur in adults with cutaneous anergy in immunocompromised patients or overwhelming TB infection. As many as a quarter of patients with active TB may have a negative TST.

TABLE 14-1 TUBERCULIN SKIN TEST INTERPRETATION

Laboratories

• In cases of pulmonary parenchymal TB, sputum analysis by acid-fast bacillus stain (AFB) and mycobacterial cultures is paramount. Cultures are necessary to determine drug susceptibility, to differentiate MTB from nontuberculous mycobacteria, and because smears alone miss up to 50% of positive samples.8

With newer laboratory techniques using rapid radiometric culture assays, culture results may finalize within 1–2 weeks.

With newer laboratory techniques using rapid radiometric culture assays, culture results may finalize within 1–2 weeks.

If sputum cannot be obtained or analysis is nondiagnostic, bronchoscopy with bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL), transbronchial lung biopsies, and brushings may facilitate diagnosis either of TB or an alternative process.

If sputum cannot be obtained or analysis is nondiagnostic, bronchoscopy with bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL), transbronchial lung biopsies, and brushings may facilitate diagnosis either of TB or an alternative process.

Caseating granulomas on histopathology are strongly suggestive of TB while cultures are pending.

Caseating granulomas on histopathology are strongly suggestive of TB while cultures are pending.

• The interferon-γ release assay (IGRA) is an alternative test for LTBI that measures the in vitro release of interferon-γ by leukocytes in response to various MTB proteins.

Two products are currently U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved, QuantiFERON-TB Gold In-Tube (QFT-GIT, Qiagen) and T-SPOT (Oxford Diagnostic Laboratories).12,13

Two products are currently U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved, QuantiFERON-TB Gold In-Tube (QFT-GIT, Qiagen) and T-SPOT (Oxford Diagnostic Laboratories).12,13

As with the TST, only those who would benefit from the treatment of latent infection should be tested. And also as with the TST, IGRA cannot distinguish latent from active MTB infection.

As with the TST, only those who would benefit from the treatment of latent infection should be tested. And also as with the TST, IGRA cannot distinguish latent from active MTB infection.

Based on a single blood sample, results are typically available within 24 hours. Shorter turn-around time may make IGRA preferable in patients for whom follow-up is uncertain.

Based on a single blood sample, results are typically available within 24 hours. Shorter turn-around time may make IGRA preferable in patients for whom follow-up is uncertain.

TST can only be positive or negative, while IGRA results may be indeterminate. At present, cut points are not based on pretest risk as they are with the TST.

TST can only be positive or negative, while IGRA results may be indeterminate. At present, cut points are not based on pretest risk as they are with the TST.

The sensitivity of the QFT-GIT is about 80% and the T-SPOT 88% compared with 70% for the TST. The estimated specificity is 97–99%.13,14 Sensitivity is likely less in HIV-infected persons.

The sensitivity of the QFT-GIT is about 80% and the T-SPOT 88% compared with 70% for the TST. The estimated specificity is 97–99%.13,14 Sensitivity is likely less in HIV-infected persons.

A major advantage of the IGRA is that prior history of BCG vaccination will not produce a false-positive result. The genome for BCG does not contain coding for the stimulating proteins.13

A major advantage of the IGRA is that prior history of BCG vaccination will not produce a false-positive result. The genome for BCG does not contain coding for the stimulating proteins.13

Infection with M. marinum or M. kansasii can result in a positive IGRA but most other nontuberculous mycobacteria do not.13,15

Infection with M. marinum or M. kansasii can result in a positive IGRA but most other nontuberculous mycobacteria do not.13,15

As IGRA is an in vitro test there is no possibility of a booster phenomenon.

As IGRA is an in vitro test there is no possibility of a booster phenomenon.

• Nucleic acid amplification (NAA) may facilitate rapid diagnosis of active TB but does not replace AFB smear and culture.16

Specificity is poor when applied to AFB smear-negative specimens but high with smear-positives.

Specificity is poor when applied to AFB smear-negative specimens but high with smear-positives.

NAA can indicate a high likelihood of MTB in conjunction with positive smears but can neither diagnose nor exclude TB in the absence of smear data.

NAA can indicate a high likelihood of MTB in conjunction with positive smears but can neither diagnose nor exclude TB in the absence of smear data.

NAA may detect genetic material from either living or dead organisms, thus cannot be used to track the efficacy of treatment.

NAA may detect genetic material from either living or dead organisms, thus cannot be used to track the efficacy of treatment.

Several next-generation NAA tests are in development.8

Several next-generation NAA tests are in development.8

Imaging

• A positive TST should be followed by CXR.

• CT scanning is more sensitive than CXR for the detection and characterization of the radiographic findings of TB and improves diagnostic accuracy.17

• In primary infection, hilar adenopathy is said to be the most consistent finding but airspace consolidation may also be seen. Pleural effusion is an occasional manifestation of primary TB. Miliary TB occurs in 2–6% of cases. 17

• Reactivation TB presents radiographically most commonly as focal or patchy heterogeneous consolidation in the apical and posterior segments of the upper lobes and the superior segments of the lower lobes. Ill-defined nodules and linear opacities are also fairly common. Cavitation is seen in a significant minority of patients. Lymphadenopathy is not very common (5–10%) and pleural effusion can be seen in 15–20% of cases. A few patients present with mass-like lesions, a tuberculoma.17

• The ability to distinguish primary infection from reactivation by radiographic appearance has been seriously questioned.18

• Atypical radiographic presentations are more common in patients with impaired immunity including lower lung disease, adenopathy, and effusions.18

• In HIV-infected patients with CD4 ≤200/µL more mediastinal and hilar lymphadenopathy and less cavitation may be seen. Extrapulmonary involvement is also more common.17

• In latent or cleared disease, healed parenchymal lesions appear radiographically as calcified nodules (Ghon lesions) and may remain associated with ipsilateral hilar adenopathy (Ranke complex).

TREATMENT

• A joint effort on the part of clinicians and public health workers is required to treat active infection and prevent spread of disease.

• Cases of TB should be reported to local public health authorities to ensure adequate therapy of the individual, to evaluate close contacts, and to track potential outbreaks.

• Several general principles guide treatment:

Duration of therapy is prolonged because MTB is a slow-growing organism.

Duration of therapy is prolonged because MTB is a slow-growing organism.

Multiple agents reduce the development of drug resistance.

Multiple agents reduce the development of drug resistance.

Culture and susceptibility data are followed to ensure drug activity.

Culture and susceptibility data are followed to ensure drug activity.

To improve adherence, the shortest sufficient course of therapy is necessary.

To improve adherence, the shortest sufficient course of therapy is necessary.

Directly observed therapy (DOT) is the preferred method of treatment for most patients and offers the highest chance of successful completion of therapy. While DOT decreases dropout from treatment, it may not improve microbiologic failure, development of resistance, or relapse rate.19,20

Directly observed therapy (DOT) is the preferred method of treatment for most patients and offers the highest chance of successful completion of therapy. While DOT decreases dropout from treatment, it may not improve microbiologic failure, development of resistance, or relapse rate.19,20

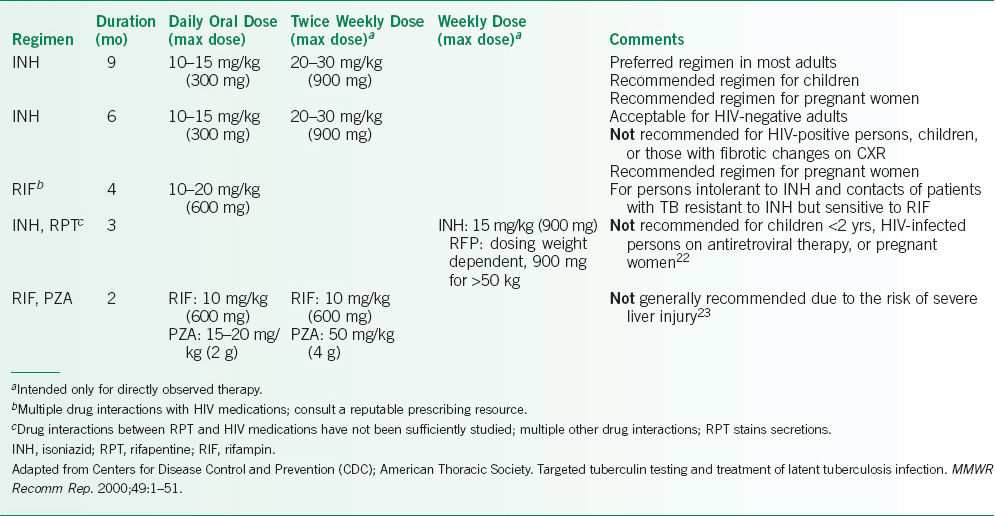

TABLE 14-2 REGIMENS FOR THE TREATMENT OF LATENT TUBERCULOSIS INFECTION

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree