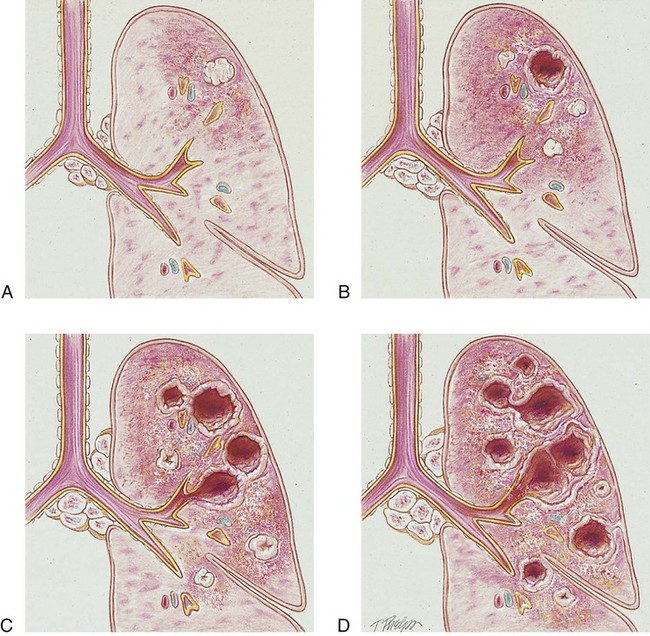

After reading this chapter, you will be able to: • List the anatomic alterations of the lungs associated with tuberculosis. • Describe the causes of tuberculosis. • List the cardiopulmonary clinical manifestations associated with tuberculosis. • Describe the general management of tuberculosis. • Describe the clinical strategies and rationales of the SOAP presented in the case study. • Define key terms and complete self-assessment questions at the end of the chapter and on Evolve. Primary TB (also called the primary infection stage) follows the patient’s first exposure to the TB pathogen, Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Primary TB begins when the inhaled bacilli implant in the alveoli. As the bacilli multiply over a 3- to 4-week period, the initial response of the lungs is an inflammatory reaction that is similar to any acute pneumonia (see Figure 15-1). In other words, a large influx of polymorphonuclear leukocytes and macrophages moves into the infected area to engulf—but not fully kill—the bacilli. This action also causes the pulmonary capillaries to dilate, the interstitium to fill with fluid, and the alveolar epithelium to swell from the edema fluid. Eventually the alveoli become consolidated (i.e., filled with fluid, polymorphonuclear leukocytes, and macrophages). Clinically, this phase of TB coincides with a positive tuberculin reaction—a positive purified protein derivative (PPD) skin test result (see discussion of diagnosis later in this chapter). Unlike pneumonia, however, the lung tissue that surrounds the infected area slowly produces a protective cell wall called a tubercle, or granuloma. In essence, the tubercles work to encapsulate—that is, put in a nutshell-like structure—the TB bacilli (see Figure 17-1, A). Although the initial lung lesions may be difficult to identify on a chest radiograph, the lesions may be seen as small, sharply defined opacities. When detected on a chest radiograph, these initial lung lesions are called Ghon nodules. As the disease progresses, the combination of tubercles and the involvement of the lymph nodes in the hilar region is known as the Ghon complex. Structurally, a tubercle consists of a central core containing TB bacilli. The central core also has enlarged macrophages with an outer wall composed of fibroblasts, lymphocytes, and neutrophils. A tubercle takes about 2 to 10 weeks to form. The function of the tubercle is to contain the TB bacilli, thus preventing the further spread of infectious TB organisms. Unfortunately, the central core of the tubercle has the potential to break down from time to time, especially in a patient with a depressed immune system. When this happens, the center of the tubercle fills with necrotic tissue that resembles dry cottage cheese. During this stage the tubercle is called a caseous lesion or caseous granuloma (see Figure 17-1, B). The patient is potentially contagious at this stage. In most cases, however, the TB bacilli are effectively contained within the tubercles. • People in institutional housing (e.g., nursing homes, prisons, homeless shelters) • People living in overcrowded conditions • Immunosuppressed patients (e.g., organ transplant patients, cancer patients) • Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)–infected patients (TB is a leading cause of death in HIV patients) If the TB infection is uncontrolled, cavitation of the caseous granuloma tubercle develops. The patient progressively experiences more severe symptoms, including violent cough episodes, greenish or bloody sputum, low-grade fever, anorexia, weight loss, extreme fatigue, night sweats, and chest pain. It is this gradual wasting of the body that provided the basis for the earlier name for TB—consumption. The patient is highly contagious at this stage. In severe cases a deep tubercle cavity may rupture and allow air and infected material to flow into the pleural space or the tracheobronchial tree. Pleural complications are common in TB (see Figure 17-1, C).

Tuberculosis

Anatomic Alterations of the Lungs

Primary Tuberculosis

Postprimary Tuberculosis

Thoracic Key

Fastest Thoracic Insight Engine