Tricuspid/Pulmonary Valve Disease

Theodore J. Kolias

USUAL CAUSES

Primary tricuspid and pulmonary valve disease occurs less often than disease of the mitral or aortic valve. This may be related to the decreased hemodynamic stress experienced by the valves on the right side of the heart, which are exposed to lower pressures than the left-sided heart valves. Lesions of the right-sided heart valves can be divided into regurgitant lesions and stenotic lesions.

The most common lesion encountered is tricuspid regurgitation. It should be emphasized that minimal tricuspid regurgitation is frequently found in normal patients and should not be considered pathologic in the absence of any other cardiac disease (1). Tricuspid regurgitation can be classified as either functional or organic. Functional tricuspid regurgitation results from dilation or distortion of the tricuspid annulus or displacement of the papillary muscles, whereas organic tricuspid regurgitation occurs as a result of intrinsic disease of the tricuspid valve leaflets or supporting apparatus. Causes of functional tricuspid regurgitation include any conditions that lead to right ventricular dilatation. Examples include right ventricular infarction and left-sided heart diseases, such as mitral stenosis or congestive heart failure, leading to pulmonary hypertension and subsequent right ventricular dilatation. Other diseases resulting in pulmonary hypertension such as pulmonary emboli or primary pulmonary hypertension may also lead to right ventricular dilatation and subsequent tricuspid regurgitation.

One cause of intrinsic tricuspid valve disease resulting in tricuspid regurgitation is rheumatic heart disease (2); this also is the most common etiology of tricuspid stenosis (3). Rheumatic heart disease most commonly affects the mitral valve (4) and often involves the aortic valve as well. As such, isolated tricuspid stenosis or regurgitation secondary to rheumatic disease in the absence of mitral or aortic valve involvement is quite rare.

In adults, the pulmonic valve is the least commonly diseased valve of all the cardiac valves. Pulmonic stenosis is usually congenital in etiology. Most frequently, it is caused by congenital fusion of the valve cusps (5). In contrast, pulmonic regurgitation is usually caused by dilation of the pulmonic valve annulus as a result of pulmonary hypertension or other conditions that dilate the pulmonary artery, such as connective tissue disease.

PRESENTING SYMPTOMS AND SIGNS

The presenting symptoms and signs of right-sided heart valve lesions are related to their etiology, their effect on venous pressure and right ventricular function, and associated conditions such as mitral stenosis or pulmonary hypertension. Typically, the clinical findings of right-sided heart valve lesions are present only in advanced cases and are commonly overshadowed by left-sided heart disease.

Tricuspid regurgitation, when severe and progressive, typically causes signs and symptoms of right-sided heart failure, such

as elevation of the jugular venous pressure, hepatomegaly, abdominal distention with ascites, edema, and congestive hepatopathy, with occasional anasarca in severe advanced cases. These patients often experience fatigue and weakness, and they may experience weight loss and cachexia. Examination of their jugular veins frequently reveals a large V wave corresponding to the regurgitant flow from ventricular contraction, as well as a steep Y descent corresponding to brisk early diastolic filling of the right ventricle. These patients may feel throbbing pulsations in their necks, corresponding with the V waves. Auscultation of the heart reveals a holosystolic murmur in the third and fourth intercostal spaces at the left sternal border. The murmur is accentuated by inspiration, a finding known as the Rivera-Carvallo sign (6). If concomitant right ventricular failure is present, then a right-sided precordial heave may be palpated, and a right-sided S3 and S4 may also be heard. If the tricuspid regurgitation is the result of pulmonary hypertension, then an accentuated pulmonic component of S2 may also be auscultated, and a diastolic murmur of pulmonic regurgitation may also be heard in the second and third intercostal spaces at the left sternal border (the Graham Steel murmur) (4,7).

as elevation of the jugular venous pressure, hepatomegaly, abdominal distention with ascites, edema, and congestive hepatopathy, with occasional anasarca in severe advanced cases. These patients often experience fatigue and weakness, and they may experience weight loss and cachexia. Examination of their jugular veins frequently reveals a large V wave corresponding to the regurgitant flow from ventricular contraction, as well as a steep Y descent corresponding to brisk early diastolic filling of the right ventricle. These patients may feel throbbing pulsations in their necks, corresponding with the V waves. Auscultation of the heart reveals a holosystolic murmur in the third and fourth intercostal spaces at the left sternal border. The murmur is accentuated by inspiration, a finding known as the Rivera-Carvallo sign (6). If concomitant right ventricular failure is present, then a right-sided precordial heave may be palpated, and a right-sided S3 and S4 may also be heard. If the tricuspid regurgitation is the result of pulmonary hypertension, then an accentuated pulmonic component of S2 may also be auscultated, and a diastolic murmur of pulmonic regurgitation may also be heard in the second and third intercostal spaces at the left sternal border (the Graham Steel murmur) (4,7).

Tricuspid stenosis may also appear with signs and symptoms of right-sided heart failure. Evaluation of the jugular venous pulse reveals a large A wave known as a “cannon A” wave corresponding to atrial contraction against a stenotic orifice. Elevation of the jugular venous pressure is usually present. Auscultation reveals a tricuspid opening snap in diastole followed by a rumbling diastolic murmur in the third and fourth intercostal spaces at the left sternal border. If the valve is mobile, then a prominent S1 may also be heard. In contrast to the murmur of mitral stenosis, both the murmur of tricuspid stenosis and the opening snap are increased in intensity with inspiration (the Rivera-Carvallo sign) (6). Because tricuspid stenosis is usually the result of rheumatic heart disease, it is almost always accompanied by rheumatic disease of left-sided heart valves, in particular the mitral valve, and as such, its manifestations may be overshadowed by those of the left-sided lesion.

Isolated disease of the pulmonic valve is quite uncommon, and when it occurs rarely causes significant symptoms (with the exception of severe congenital pulmonic stenosis). Because pulmonic regurgitation most often occurs as the result of pulmonary hypertension, its manifestations are often overshadowed by those of the pulmonary hypertension itself. Only rarely does pulmonic regurgitation itself cause clinical manifestations; when they occur, they are related to right ventricular failure from a right ventricular volume overload. On physical examination, pulmonic regurgitation is characterized by a diastolic murmur best heard in the second and third intercostal spaces at the left sternal border. If associated pulmonary hypertension is present, then the intensity of the pulmonic component of S2 may be increased. Signs of right ventricular failure also may be present, such as a prominent right ventricular heave and right-sided S3 and S4 heart sounds (6).

Pulmonic stenosis is characterized by a midsystolic crescendo murmur best heard in the second left intercostal space at the left sternal border. Often an ejection click precedes the murmur, and, in contrast to other right-sided cardiac murmurs, the intensity of the ejection click decreases with inspiration (7). Associated findings may include a right-sided S4 and a right ventricular heave. Symptoms typically develop when the stenosis is severe, and they include fatigue, dyspnea, exercise intolerance, lightheadedness, syncope, angina, and manifestations of right ventricular failure.

HELPFUL TESTS

The electrocardiogram may be useful in the evaluation of patients with tricuspid or pulmonic valve disease. In patients with pulmonic stenosis, the electrocardiogram often reveals evidence of right ventricular hypertrophy, particularly if the pulmonic stenosis is severe. In patients with isolated tricuspid stenosis, the electrocardiogram may reveal

evidence of right atrial enlargement, with a notable absence of right ventricular hypertrophy. If concomitant mitral stenosis is found, then evidence of left atrial enlargement may also be apparent. Atrial fibrillation is also commonly seen.

evidence of right atrial enlargement, with a notable absence of right ventricular hypertrophy. If concomitant mitral stenosis is found, then evidence of left atrial enlargement may also be apparent. Atrial fibrillation is also commonly seen.

The electrocardiographic findings in patients with tricuspid or pulmonic regurgitation depend on the etiology of the lesion. In cases of regurgitation secondary to pulmonary hypertension, evidence of right ventricular hypertrophy may exist. If right ventricular enlargement has occurred, then a complete or incomplete right bundle-branch block may be present. If severe right atrial enlargement has also occurred, then Q waves may be noted in leads V1 and V2 that may mimic an anteroseptal myocardial infarction.

The radiographic findings of right-sided heart valve lesions are fairly nonspecific. Tricuspid and pulmonic regurgitation frequently lead to cardiomegaly from right ventricular enlargement. Both tricuspid regurgitation and tricuspid stenosis may lead to right atrial enlargement and prominence of the right heart border of the cardiac silhouette (4). In the absence of concomitant mitral valve disease, most striking is the absence of radiographic signs of pulmonary edema, despite the clinical signs and symptoms of right-sided heart failure.

The mainstay of diagnostic testing in patients with tricuspid or pulmonic valve disease is echocardiography. This technique allows direct visualization of the tricuspid and pulmonic valves, thus providing evidence of the etiology of the valve lesion. In addition, the mitral and aortic valves can be evaluated, as can the right atrial and right ventricular size and function. Color Doppler imaging can be used to determine the amount of tricuspid or pulmonic regurgitation. Spectral Doppler can be used to measure velocities and to determine pressure gradients across the tricuspid and pulmonic valves, thus allowing the grading of the severity of tricuspid or pulmonic stenosis. Finally, echocardiography can be used to identify other conditions mimicking or causing valvular heart disease, such as atrial tumors or endocarditis.

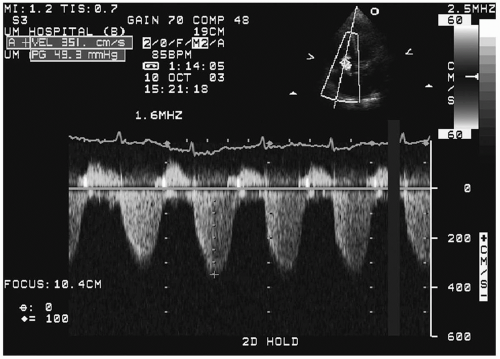

The echocardiographic determination of the severity of tricuspid regurgitation is based on a number of parameters, including the regurgitant jet area, the size of the convergence zone, and the presence or absence of flow reversal in the inferior vena cava or hepatic veins. Ancillary information such as the presence of a right ventricular volume-overload pattern (flattening of the interventricular septum during diastole) can also provide additional evidence of significant tricuspid or pulmonic regurgitation. In addition, spectral Doppler can be used to measure the velocity of the tricuspid regurgitation jet; this velocity can then be used to determine the right ventricular systolic pressure (Fig. 25.1). In the absence of pulmonic stenosis, the right ventricular systolic pressure can be used as a surrogate for the pulmonary artery systolic pressure, thus allowing pulmonary hypertension to be diagnosed (1).

Invasive cardiac catheterization of patients with tricuspid or pulmonic valve disease may be helpful in cases in which direct measurement of the pulmonary artery pressure is necessary, particularly if the Doppler signal on the tricuspid regurgitation jet is insufficient to allow accurate measurement of the right ventricular systolic pressure gradient. In addition, cardiac catheterization is indicated in patients with pulmonic stenosis with a peak pressure gradient greater than 36 mm Hg who are being considered for balloon valvuloplasty (5).

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Tricuspid Stenosis

The most common cause of tricuspid stenosis is rheumatic heart disease. In one series evaluating the etiology of operatively excised stenotic tricuspid valves, rheumatic heart disease accounted for 93% of all excised valves (3). As mentioned previously, isolated tricuspid stenosis secondary to rheumatic heart disease is quite uncommon, however, and is usually accompanied by rheumatic mitral disease and often aortic disease as well. Other causes of tricuspid

stenosis include carcinoid heart disease (8,9), Loffler (eosinophilic) endocarditis (6), and prosthetic tricuspid valve malfunction (Table 25.1).

stenosis include carcinoid heart disease (8,9), Loffler (eosinophilic) endocarditis (6), and prosthetic tricuspid valve malfunction (Table 25.1).

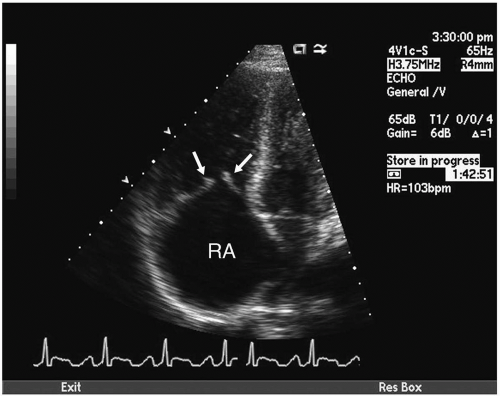

Carcinoid heart disease is caused by a carcinoid tumor, which is a rare malignancy that secretes vasoactive substances including serotonin, bradykinin, and histamines (6). Patients with carcinoid typically are first seen with flushing, diarrhea, and bronchospasm, and they have elevated urinary levels of the serotonin metabolite 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid (8). The tumor frequently originates in the appendix, ileum, small intestine, or rectum (6). It is thought that the vasoactive substances secreted by the tumor cause endothelial damage on the right side of the heart, particularly on the right-sided heart valves. The result is fibrosis and thickening of the right-sided heart valves, most commonly the tricuspid valve (Fig. 25.2). Because these vasoactive substances are metabolized by the lung, left-sided valvular disease is very uncommon and is thought to occur only in the presence of lung metastases or a lesion allowing right-to-left shunting (6).

TABLE 25.1. Causes of tricuspid stenosis | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Loffler endocarditis may also cause tricuspid stenosis through formation of plaques on the right side of the heart, including on the tricuspid valve. The right ventricular plaques seen in this disease are frequently covered with thrombi (6). Other conditions that can

mimic tricuspid stenosis by causing obstruction of flow across the tricuspid valve include tumors such as renal cell carcinoma or right atrial myxoma, and tricuspid valve endocarditis with very large vegetations causing obstruction of blood flow.

mimic tricuspid stenosis by causing obstruction of flow across the tricuspid valve include tumors such as renal cell carcinoma or right atrial myxoma, and tricuspid valve endocarditis with very large vegetations causing obstruction of blood flow.

Tricuspid Regurgitation

Diseases causing tricuspid regurgitation can be divided into two categories: conditions causing organic tricuspid valve disease, and conditions causing functional (nonorganic) tricuspid valve disease (Table 25.2). Organic tricuspid valve disease is the less common of the two, and it has numerous etiologies. These include rheumatic heart disease, carcinoid heart disease, and Loffler (eosinophilic) endocarditis, all of which can also cause tricuspid stenosis, as described earlier. Other causes include tricuspid valve prolapse, endocarditis, trauma, Marfan disease (2), radiation valve disease (2), prosthetic valve malfunction, pacemaker wire interference, and congenital abnormalities, the most common of which is Ebstein anomaly. Ebstein anomaly consists of displacement of the septal and posterior leaflets of the tricuspid valve apically into the right ventricle (10). As a result, abnormal coaptation of the valve leaflets of the tricuspid valve result in various amounts of tricuspid regurgitation. This abnormality is easily detected with echocardiography.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree