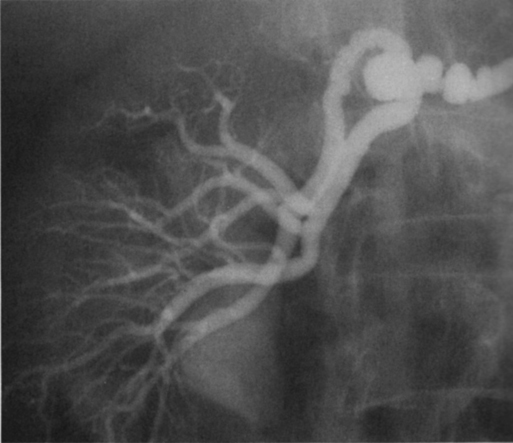

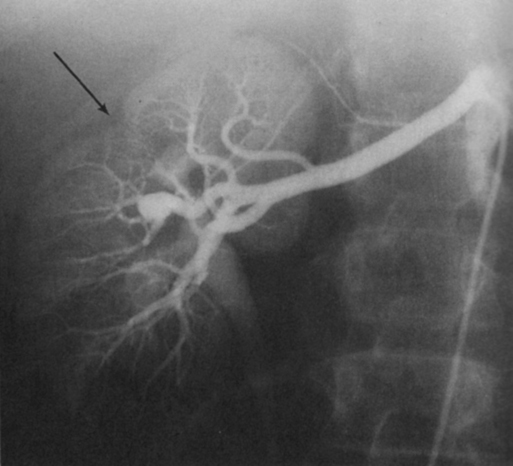

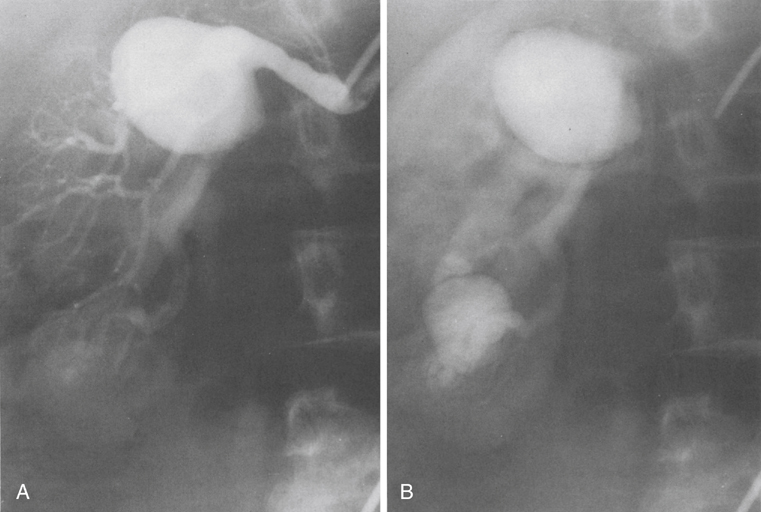

Renal artery aneurysms represent an unusual vascular disease that has been encountered with increasing regularity in clinical practice. In part, this reflects their frequent incidental recognition as a consequence of the proliferation of noninvasive imaging for nonvascular diseases. The incidence of true renal artery aneurysms approaches 0.1%, a figure derived from the 0.09% incidence of these lesions in approximately 8500 patients subjected to arteriographic studies for nonrenal disease. Women are slightly more likely than men to have renal artery aneurysms. Most renal artery aneurysms are saccular (Figure 1). Seventy-five percent are located at first- or second-order renal artery bifurcations. Intraparenchymal aneurysms occur in less than 10% of cases. Two distinct histologic categories of aneurysms are recognized. The first is related to congenital defects, and the second is associated with arteriosclerosis. Arteriosclerotic changes are considered a secondary event rather than a primary cause of most aneurysms, but they likely cause a further loss of the vessel wall’s integrity. Most renal artery aneurysms are a consequence of preexisting congenital defects with internal elastic lamina defects or deficiencies of medial smooth muscle that can exist at bifurcations, causing the vessel wall to become functionally inadequate at withstanding normal arterial pressure with development of saccular macroaneurysms at these sites. Arterial fibrodysplasia can contribute to other aneurysms (Figure 2). Elevated blood pressures, which occur in nearly 80% of patients with renal artery aneurysms, certainly enhance the evolution of these aneurysms, but the hypertension is actually an uncommon consequence of the aneurysm itself. Most renal artery aneurysms are asymptomatic. An ill-defined relationship exists between renal artery aneurysms and elevated arterial blood pressure. In an occasional patient, an aneurysmal thrombus embolizes or propagates and occludes a distal artery, thereby producing renal ischemia and renovascular hypertension (Figure 3). Computational modeling suggests that deformation of branches adjacent to aneurysms at bifurcations can produce a pressure gradient and also cause renovascular hypertension. It has also been hypothesized that energy dissipation in large aneurysms can cause a similar drop in renal blood pressure and result in systematic blood pressure increases as a result of renin release. No direct evidence of this has been documented in the literature. Intrinsic stenotic disease adjacent to an aneurysm, not always evident on preoperative arteriograms, is a more likely cause of secondary hypertension in other patients, especially those with renal arterial fibrodysplasia. Rupture occurs in less than 3% of true renal artery aneurysms. It has been suggested that aneurysms less than 1.5 cm in diameter, calcified aneurysms, and those occurring in normotensive patients are not likely to rupture, but this has not proved to be the case. Rupture may be overt into the retroperitoneal and abdominal cavity or covert into an adjacent renal vein (Figure 4).

Treatment of Renal Artery Aneurysms

Pathogenesis

Clinical Presentation

Thoracic Key

Fastest Thoracic Insight Engine