Chapter 8 Treatment of Perforating Veins

Historical Background

Although the role of perforator veins (PVs) in the development of signs and symptoms remains unclear, the number of incompetent PVs and the size of both competent and incompetent PVs have been shown to increase with worsening chronic venous disease (CVD).1–4 Furthermore, it was recently reported that the duration of outward flow in these veins was longer in patients with ulcers compared with those in lower classes of CVD.2

Etiology and Natural History of Disease

Reflux in PVs is defined as outward flow from the deep to the superficial veins. It has been suggested that high flow from the deep veins during muscular contraction eventually renders the PVs incompetent.5 The etiology of venous reflux in superficial veins and PVs is unknown. The most predominant theory is that the weakening of the venous wall eventually leads to valve failure.6 During early stages of the disease, reflux is most prevalent in the superficial veins.7–9 Others have also suggested that reflux in the PVs is caused by volume overload at the reentry points of incompetent superficial veins.10,11 However, direct evidence for both of these theories is lacking because most investigations have been cross-sectional population studies without sufficient longitudinal study regarding disease progression.

Labropoulos et al.11 identified two other patterns by which previously competent PVs become incompetent—these were ascending development and new sites becoming incompetent. The ascending development of reflux into PVs from previously competent segments of superficial veins was more prevalent. A smaller number of incompetent PVs were detected in new locations that previously did not have reflux in any system PV reflux was always associated with reflux in an adjacent superficial vein and underscores the important role of superficial vein reflux in the development of PV incompetence. Because most limbs in the early stages of CVD exhibit reflux in the superficial veins only, it can be assumed that one of the mechanisms for development of PV insufficiency involves the presence of reflux in an adjacent superficial vein segment that acts as a capacitor for the refluxing PV. As local hemodynamic conditions change and as intravenous pressure increases, the diameter of the PV increases, and the PV valve becomes incompetent. This may be in combination with or separate from primary venous wall disease.

Deep vein reflux is not required for development of PV incompetence in primary venous disease. Rather, deep vein reflux can develop as a result of increased flow from the incompetent superficial veins through the PV, the diameter of which has increased. Labropoulos et al.11 showed that only five new incompetent PVs were seen in association with juxtaposed reflux in the deep vein. At all five sites, deep vein reflux was not present at the time of the initial duplex study, when the adjacent PV was still competent; the deep venous incompetence developed simultaneously with PV incompetence. Superficial vein reflux was present at all sites.

Finally, this study also suggested that the development of reflux in previously normal PVs was seen in association with worsening of the clinical stage of CVD in 40% of limbs. Although the worsening of the clinical stage cannot be attributed to extension of reflux in the PVs alone, one can assume that the natural history of long-standing reflux in the superficial veins is that of progressive deterioration, with extension of reflux to other previously competent segments of the superficial veins and their associated PVs.12

Patient Selection

In general, PVs should be reserved for specific situations:

Endovascular Instrumentation

A 16-gauge angiocath (for a 600-µm laser fiber) or a 21-gauge micropuncture needle (for a 400-µm laser fiber) can be used for laser ablation.

A 16-gauge angiocath (for a 600-µm laser fiber) or a 21-gauge micropuncture needle (for a 400-µm laser fiber) can be used for laser ablation.Operative Steps

Percutaneous ablation of perforators (PAPs) was coined by Elias and Peden.12 The basic method involves (1) ultrasound-guided intraluminal access; (2) introduction of some ablative element (chemical or thermal); (3) confirmation of initial treatment success; and (4) follow-up of treatment success. Thus far, the techniques used have been either chemical (sodium tetradecyl sulfate [STS], aethoxysclerol, or sodium morrhuate)13,14 or thermal (radiofrequency [RF] or laser).15–17

PAPs Technique: Chemical Ablation

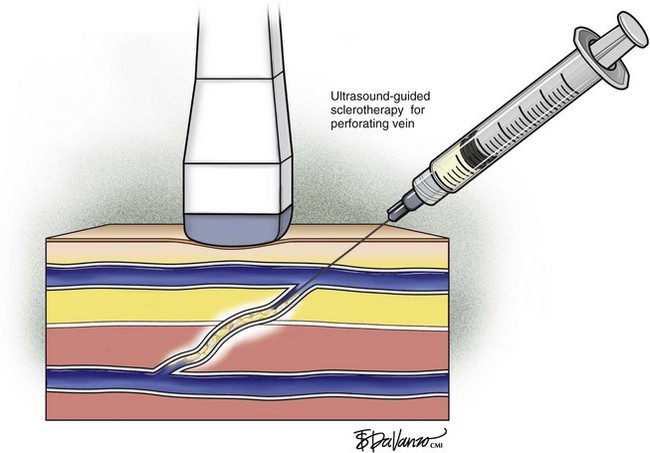

Ultrasound-guided sclerotherapy (UGS) (Fig. 8-1) is an effective and durable method of eliminating incompetent PVs and results in significant reduction of symptoms and signs as determined by venous clinical scores. As an alternative to open interruption or SEPS, UGS may lead to fewer skin and wound-healing complications. Little has been published regarding the outcomes following UGS for PVs.

In a series by Masuda et al.,13 patients primarily had isolated perforator disease (83%) without concomitant axial reflux from the thigh to the calf in the saphenous or deep systems. Clinical improvement following UGS was suggested by improvement of the Venous Clinical Severity Score (VCSS) and Venous Disease Severity (VDS) and lack of perforator recurrence with a mean follow-up of 20 months. In this study, successful obliteration of PVs with no recurrent symptoms was 75%. Perforator recurrence occurs particularly in those with ulcerations, and therefore surveillance duplex scanning after UGS and repeat injections may be needed. This study suggests that patients with perforator disease without axial reflux appear to benefit from injection sclerotherapy.

In 1992, Thibault and Lewis17 reported their early experience with injection of incompetent PVs by using ultrasound guidance and showed that PVs remained successfully obliterated in 84% at 6 months after treatment. In 2000 at the Pacific Vascular Symposium in Hawaii, Jerome Guex18 from France reported his experience with direct perforator treatment with ultrasound guidance. The sclerosing agent used was sodium tetradecyl sulphate (Sotradecol) (3%) (Bioniche Life Sciences Inc., Belleville, Ontario, Canada) or polidocanol (3%) for veins larger than 4 mm, and a more dilute solution was used for veins smaller than 4 mm. He estimated that 90% of PVs could be eliminated after one to three sessions of injections.

This method also involves ultrasound-guided access and confirmation with aspiration of blood. Many types of sclerosants have been used: sodium morrhuate, STS, and aethoxysclerol. Some advocates use the sclerosant in a liquid state. More recently, foam sclerotherapy has been advocated as being more efficacious. Most studies use STS 3% in the liquid form, injecting 0.5 to 1 ml of sclerosant or sodium morrhuate 5% in a similar manner, with care being taken not to inject the accompanying artery.14,19 After infusion of the sclerosant, compression is applied with wraps or stockings and direct pressure over the treated PV.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree