Treatment of Femoral and Popliteal Artery Aneurysms

Patrick J. O’Hara

Definition and Natural History

Aneurysms involving the femoro-popliteal arterial segment are the most common of the peripheral aneurysms. Nevertheless, controversy still persists regarding the optimal management of these lesions, particularly those that are asymptomatic at the time of their discovery. Natural history data are inconclusive for asymptomatic aneurysms, particularly if they are small, in part because of problems with definition. While it is agreed that a focal enlargement in artery diameter of at least 50%, when compared to the expected normal diameter of the artery, is an aneurysm, in practice, the diagnosis of small aneurysms may be unclear because the normal arterial diameters may vary with age and gender. Furthermore, the extent of the dilatation and the presence of mural thrombus may influence the natural history of these lesions. Clearly, the surgical treatment of arteriomegaly, involving the entire femoropopliteal segment, is more involved than that required for repair of a discrete lesion of the femoral or popliteal artery.

On histologic examination, true aneurysms exhibit dilatation of all three layers of the arterial wall and are best considered degenerative aneurysms. In contrast, the wall of a pseudoaneurysm does not contain all three microscopic layers, and the pulsatile mass is the result of mechanical disruption of the arterial wall resulting from trauma, infection, or disruption of an arterial anastomosis. The preponderance of popliteal aneurysms is of the true, or degenerative, variety, whereas most femoral aneurysms encountered in current clinical practice are pseudoaneurysms.

There is a strong association between the presence of true aneurysms involving the femoral or popliteal arteries and the presence of aneurysmal disease involving the contralateral extremity or other arterial segments. For example, about one third to one half of those patients presenting with femoro-popliteal aneurysms will be found to have aneurysms involving the infrarenal, aorto-iliac segment. Conversely, a patient initially presenting with an aneurysm involving the aorto-iliac segment is also more likely to have an associated femoral or popliteal aneurysm, an observation that mandates careful evaluation of these patients for associated aneurysms.

The natural history of degenerative femoral aneurysms is not known with certainty because these aneurysms are unusual lesions and often come to clinical attention only when they have become symptomatic or are discovered as incidental findings on imaging studies done for other purposes. These aneurysms are thought to be relatively benign lesions that rarely rupture, but they can occasionally become limb threatening as a source of embolic material. If they are large, however, they can be associated with leg swelling or pain from compression of the neighboring femoral vein or femoral nerve irritation. Conversely, femoral artery pseudoaneurysms are more common lesions and are also thought to be more threatening because of their propensity for expansion, rupture, thrombosis, or embolization. Popliteal aneurysms, in contrast, are usually degenerative aneurysms and rarely rupture. However, they are associated with the development of limb-threatening ischemia in from 30% to 40% of patients because of either thrombosis of the aneurysm or occlusion of the distal arterial outflow bed resulting from emboli that originate from the aneurysm. This propensity, furthermore, is not thought to be related to the size of the popliteal aneurysm but merely to its presence. Large popliteal aneurysms can also cause pain or edema from their mass effect; an important issue is planning operative strategy.

Diagnostic Considerations

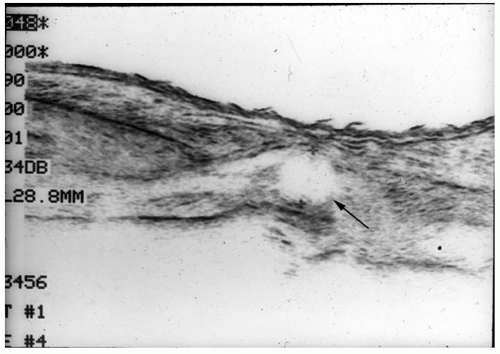

The diagnosis of femoral or popliteal aneurysms can often be made based upon a careful history and physical examination, if the index of suspicion is sufficiently high. Because the popliteal artery is surrounded by the calf muscles, the diagnosis of popliteal aneurysm is often more difficult than that of femoral aneurysm, especially if the patient is obese. Nevertheless, the detection of a large, pulsatile mass in the groin or popliteal space, especially if the patient is known to have an aorto-iliac aneurysm, warrants objective imaging to evaluate the femoral or popliteal arteries. On occasion, a cystic lesion that transmits the arterial pulse, such as a lymphocele in the groin or a Baker cyst in the popliteal space, may be mistaken for an aneurysm. The diagnosis is usually confirmed by imaging studies, which are most useful to gauge the size and extent of the aneurysm. Duplex ultrasonography is the most useful preliminary imaging modality (Fig. 24-1), while magnetic resonance (MR) and computerized axial tomographic (CAT) scans are also useful methods in determining the size and extent of the aneurysms (Fig. 24-2). Arteriography is useful in planning surgical treatment, because it can define the extent of associated inflow and outflow occlusive disease; however, it is of only

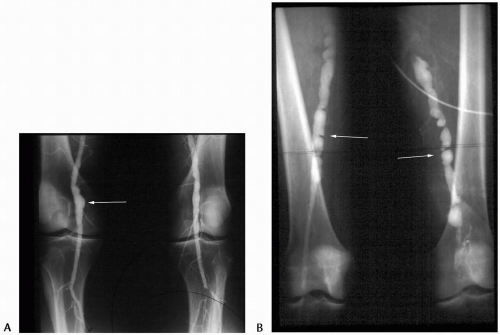

limited use in determining the size of the aneurysm because of the presence of mural thrombus lining the aneurysm sac. Especially in the presence of multiple aneurysms or generalized arteriomegaly, it is important to assess the extent of the involved arterial segment that will require repair in order to plan effective operative strategy. Focal lesions may be approached segmentally, with shorter arterial grafts than those required for extensive, diffuse disease that may require bypass of the entire femoro-popliteal arterial segment (Fig. 24-3). In the latter circumstance, it may also be necessary to repair co-existing femoral and popliteal aneurysms simultaneously.

limited use in determining the size of the aneurysm because of the presence of mural thrombus lining the aneurysm sac. Especially in the presence of multiple aneurysms or generalized arteriomegaly, it is important to assess the extent of the involved arterial segment that will require repair in order to plan effective operative strategy. Focal lesions may be approached segmentally, with shorter arterial grafts than those required for extensive, diffuse disease that may require bypass of the entire femoro-popliteal arterial segment (Fig. 24-3). In the latter circumstance, it may also be necessary to repair co-existing femoral and popliteal aneurysms simultaneously.

Figure 24-2. Computerized axial tomographic (CAT) scan of a left common femoral aneurysm (arrow). Multiple slices are used to delineate the proximal and distal extent of the aneurysm. |

Principles of Treatment

The four fundamental principles in the treatment of femoral and popliteal aneurysms are:

To eliminate the aneurysm as a potential source of embolic material or as a source of hemorrhage from rupture

To eliminate the mass effect if the aneurysm is large and compressing other structures

To maintain distal perfusion in a durable fashion

To minimize the risk of recurrence

In the presence of multiple aneurysms, the decision to treat them simultaneously or segmentally depends upon prioritization of the most threatening lesion, the extent of the lesions, and the condition of the patient. In general, it is better to treat the lesions segmentally, if the anatomy permits, and begin with the symptomatic or most threatening lesion. Other factors important in the long-term success of reconstructions that are performed to repair femoral and popliteal aneurysms are the choice of graft material, the length of the bypass graft required, and the state of the distal runoff bed. In general, short grafts are preferable and, while autogenous conduits of adequate saphenous vein are preferable in the popliteal region, short synthetic grafts function well in the femoral position.

Indications for Treatment

Femoral Aneurysms

There is consensus that treatment is required for all symptomatic femoral aneurysms, regardless of their etiology. Prompt repair is required for those patients

presenting with limb-threatening ischemia, hemorrhage, or local symptoms of pain or compression. For asymptomatic, true femoral aneurysms, the indications to intervene are somewhat controversial, because the natural history of these lesions is thought to be relatively benign. Most would agree that asymptomatic true femoral aneurysms larger than 2.5 cm at presentation, or demonstrating enlargement on serial imaging studies, should be repaired, especially if the patient is a good surgical candidate with a reasonable life expectancy. It may also be necessary to repair a small, asymptomatic femoral aneurysm in order to provide a platform for a more distal bypass that is required to repair a popliteal aneurysm. Similarly, femoral aneurysm repair is required when a more proximally based bypass graft is brought to the femoral region in a patient with a femoral aneurysm, because the development of a subsequent anastomotic pseudoaneurysm is likely if the graft limb is implanted directly into the aneurysmal femoral artery. In contrast, femoral artery pseudoaneurysms, especially anastomotic pseudoaneurysms, are probably more threatening, and an aggressive approach to management of these lesions is warranted, regardless of the presence of symptoms, unless the patient is a poor surgical risk with a limited life expectancy.

presenting with limb-threatening ischemia, hemorrhage, or local symptoms of pain or compression. For asymptomatic, true femoral aneurysms, the indications to intervene are somewhat controversial, because the natural history of these lesions is thought to be relatively benign. Most would agree that asymptomatic true femoral aneurysms larger than 2.5 cm at presentation, or demonstrating enlargement on serial imaging studies, should be repaired, especially if the patient is a good surgical candidate with a reasonable life expectancy. It may also be necessary to repair a small, asymptomatic femoral aneurysm in order to provide a platform for a more distal bypass that is required to repair a popliteal aneurysm. Similarly, femoral aneurysm repair is required when a more proximally based bypass graft is brought to the femoral region in a patient with a femoral aneurysm, because the development of a subsequent anastomotic pseudoaneurysm is likely if the graft limb is implanted directly into the aneurysmal femoral artery. In contrast, femoral artery pseudoaneurysms, especially anastomotic pseudoaneurysms, are probably more threatening, and an aggressive approach to management of these lesions is warranted, regardless of the presence of symptoms, unless the patient is a poor surgical risk with a limited life expectancy.

Popliteal Aneurysms

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree