Treatment of Combined Symptomatic Carotid and Subclavian Artery Atherosclerosis

JAMES M. ESTES

Presentation

A 65-year-old woman presents with a 3-week history of intermittent right hand numbness, dizziness, and flashing colored lights in both eyes. The episodes last a few minutes and then completely subside. Her past medical history includes type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and hypothyroidism. Physical examination reveals bilateral cervical bruits and an absent brachial pulse in the left arm.

Differential Diagnosis

This patient’s neurologic symptoms are consistent with both vertebrobasilar and hemispheric ischemia. The flashing colored lights in a binocular distribution suggest involvement of the visual cortex in the posterior cerebrum, and the dizziness may be related to ischemia of other hindbrain structures. These symptoms are indicative of symptomatic subclavian steal.

Evidence of subclavian artery disease is occasionally discovered on routine physical examination in older patients with atherosclerotic risk factors. However, surgical reconstruction for this condition is unusual and represents less than 5% of arterial cases in busy academic centers, according to Evans and Shepard. The Joint Study of Extracranial Arterial Occlusion found associated subclavian or innominate disease in 17% of patients undergoing arteriography for suspected carotid disease, according to Fields and Lemak.

The true incidence of severe subclavian artery disease is largely unknown, because most patients are asymptomatic and are discovered incidentally after finding either decreased pulses or a lower blood pressure in one arm. Symptoms generally reflect vertebrobasilar insufficiency and typically include dizziness, visual symptoms, and syncope. The classic symptoms of vertebrobasilar insufficiency induced by arm exercise are uncommon, and in most cases, the symptoms are provoked by orthostatic maneuvers or excessive dosages of antihypertensives. Arm claudication may be present as well, but overt arm or hand ischemia is uncommon and usually indicates multilevel occlusive disease. The presence of hemispheric or monocular symptoms suggests coexisting carotid bifurcation disease.

A subset of patients who have had coronary bypass using the left internal mammary artery (LIMA) may present with recurrent angina due to hemodynamically limiting subclavian disease proximal to the LIMA origin. This condition is referred to as coronary steal syndrome.

The hand and arm numbness suggest ischemia in the distribution of the middle cerebral artery, implicating a critical carotid lesion as a cause, most likely from a hemodynamic and not embolic etiology in this case. An angiogram is ordered.

Workup

Arch Aortogram

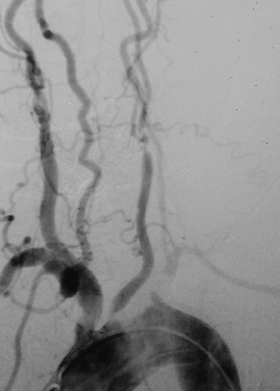

Arch aortogram demonstrates severe proximal left subclavian artery disease, a moderately severe lesion in the proximal left common carotid artery, and severe left carotid bifurcation disease (Fig. 1).

FIGURE 1 Arch aortogram revealing stenosis at the origin of the left common carotid artery, stenosis at the left carotid bifurcation, and occlusion of the left subclavian artery.

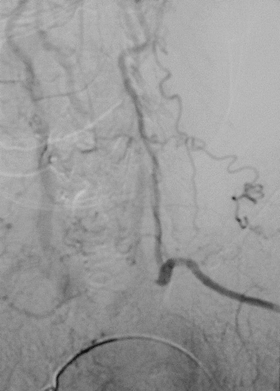

Delayed arteriographic sequence demonstrates retrograde left vertebral flow and filling of the subclavian artery distal to the occlusive lesion (Fig. 2).

FIGURE 2 Delayed imaging demonstrating collateral filling of the left subclavian artery via retrograde flow in the left vertebral artery. These findings are characteristic of subclavian steal syndrome.

Diagnosis and Treatment

Symptomatic left subclavian steal and carotid atherosclerosis.

Left carotid endarterectomy, intraoperative retrograde angioplasty/stenting of the proximal left common carotid artery, carotid-to-subclavian bypass using 8-mm PTFE.

The initial diagnostic test of choice is duplex ultrasound imaging. Often the subclavian lesion can be identified, and the presence of retrograde vertebral flow confirms the diagnosis of subclavian steal. It is also crucial to assess the carotid bifurcations, because significant coexisting disease is common and should be considered for contemporaneous treatment. Arteriography is the definitive test because it provides a dynamic and more detailed view of overall anatomy, particularly the origins of the great vessels, which are difficult to identify with ultrasonography.

Treatment is indicated when symptoms of cerebral or arm ischemia are present. The most common surgical procedures performed are carotid-subclavian bypass and subclavian-carotid transposition. Our preference is bypass using a short 8-mm polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) graft, because the transposition requires much more proximal dissection of the subclavian artery, putting the thoracic duct, phrenic nerve, and vertebral artery at greater risk of injury.

If the ipsilateral carotid artery is not suitable for inflow, extra-anatomic configurations such as axillo-axillary, subclavian-subclavian, and even femoro-subclavian bypasses can be constructed. However, direct great vessel reconstruction is preferred in these circumstances, using a graft off the ascending aorta in patients medically fit enough to tolerate median sternotomy.

Endovascular treatment of subclavian disease is also an important therapeutic option. In general, long-term patency is modestly reduced compared with surgical reconstruction. Yet, this approach may be more desirable for patients with more significant comorbidity or active myocardial ischemia from coronary steal.

Surgical Approach

This patient has both symptomatic subclavian steal and ipsilateral carotid bifurcation disease. Surgical management is complicated by the moderate focal stenosis of the left common carotid origin, which renders it disadvantageous as inflow for a carotid subclavian bypass. You elect to perform a carotid-to-subclavian bypass and carotid endarterectomy with endovascular treatment of the common carotid artery disease, because the lesion is focal and the remainder of the artery is normal. The alternatives of aortocarotid/subclavian bypass or extra-anatomic reconstruction are less desirable for this patient because of her comorbidities.

The patient is positioned for carotid endarterectomy, with the neck extended and rotated to the right. The subclavian and proximal carotid arteries are dissected out through a medial supraclavicular incision. The clavicular head and a portion of the sternal head of the sternocleidomastoid muscle are divided. The phrenic nerve is gently retracted medially and the anterior scalene muscle divided, exposing the subclavian artery. A second incision is made along the upper anterior border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle, providing the typical exposure required for carotid endarterectomy.

Via the supraclavicular incision, a tunnel is made posterior to the jugular vein for the bypass, avoiding injury to the vagus nerve. The common carotid anastomosis is performed first to an 8-mm externally supported PTFE graft, which facilitates positioning of the graft on the lateral aspect of the vessel for a favorable lie. Prior to completing the anterior wall of the anastomosis, a short 9-French sheath is advanced through the arteriotomy retrograde down the common carotid artery and then controlled with a Rummel tourniquet. Using road-mapped angiographic imaging, an 8-mm self-expanding stent is placed across the lesion, followed by an 8-mm angioplasty balloon. The stent is positioned to flare slightly into the aortic lumen. Completion angiography is performed. At this time, the sheath is removed and the anastomosis completed. The graft is tunneled behind the jugular vein, and the subclavian anastomosis is performed.

After deployment of the stent, the vessel is vigorously flushed prior to completion of the bypass. Carotid endarterectomy is then performed using a Dacron patch and routine shunting as the last step to minimize the development of stasis thrombi on the fresh patch and neointima during clamping of the common carotid artery for the bypass and stent. A closed suction drain is placed in the supraclavicular incision.

Intraoperative Angiography Report

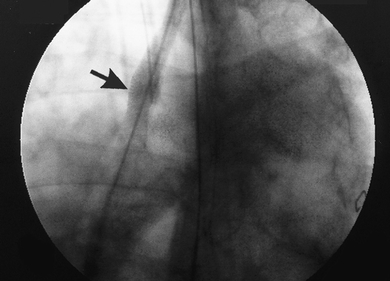

Intraoperative completion arteriogram following primary stenting and touch-up angioplasty of the proximal common carotid artery reveals no residual stenosis (Fig. 3; arrow indicates the treated area of the vessel).

FIGURE 3 Completion angiogram following primary stenting of the origin of the left common carotid artery (arrow).