Treatment of Carotid Body Tumors

Elliot L. Chaikof

Diagnostic Considerations

Carotid body tumors (CBTs) occur with an incidence of approximately one in 30,000, primarily in the fifth decade of life, and are observed with roughly equal frequency in male and female patients. However, CBT have been noted in patients as young as 12 years old, and among populations residing at high altitudes, female patients appear to be more likely than males to develop CBT. Cases are most commonly sporadic, but 10% to 20% appear to be familial. Familial CBTs are often bilateral, occurring in synchronous or metachronous fashion, and may be associated with other paragangliomas. Although familial CBTs are infrequent, their presence offers an opportunity to screen family members, leading to early diagnosis and treatment. Although an autosomal dominant mode of genetic transmission with complete penetrance is commonly accepted for familial CBTs, a paternally derived gene for multiple paraganglioma syndrome has recently been reported.

A CBT typically presents as a palpable and painless mass in the anterior triangle of the neck in the absence of associated thrill or bruit. The differential diagnosis includes cervical lymphadenopathy, carotid artery aneurysm, branchial cleft cyst, laryngeal carcinoma, and metastatic tumor. A CBT can usually be displaced laterally but not vertically. Moreover, lateral displacement results in movement of the common carotid pulse in the same direction as the tumor. This finding has been referred to as Fontaine’s sign and may assist in differentiating a CBT from other lesions by physical examination. In tumors larger than 5 cm, cranial nerve palsy may be observed and most often involves the vagus and hypoglossal nerves.

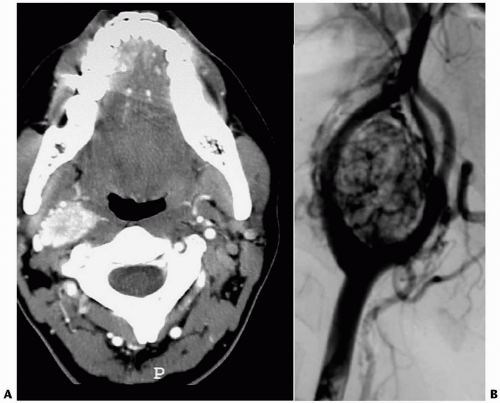

The most characteristic histologic feature of these lesions is the uniform nesting arrangement of the cells, most of which are chief cells containing neurosecretory granules, with sustentacular cells and a vascular stroma comprising the remainder of the tumor. Most CBT appear to be nonsecreting. The performance of a pre-operative biopsy is to be avoided because of the vascular nature of the tumor. Duplex and CT imaging are the diagnostic procedures of choice (Fig. 31-1).

Pathogenesis

Tumors that develop at the bifurcation of the common carotid artery are the most common form of cervicocranial paragangliomas. These neoplasms originate from neuroectodermal paraganglion cells, distributed from the skull base down the aortic arch. Characteristically, paraganglion cells of the carotid body are chemoreceptor cells and detect change in pO2, pCO2, and pH. As such, CBTs have been reported to be more prevalent in individuals who live at high altitudes and who are subjected to chronic hypoxia as a stimulant for carotid body cell hyperplasia. Although paraganglion cells are part of the neuroendocrine amine precursor uptake and decarboxylation system, the secretion of catecholamines by these tumors is unusual. In the sporadic form, fewer than 5% of patients have bilateral tumors, but 30% with the familial form will eventually develop bilateral tumors. Of note, CBT grow very slowly. Metastases have been noted in 5% to 10% of patients and may develop many years after original tumor resection. Most commonly, tumor spread occurs to the local lymph nodes and infrequently to the liver or lungs. Long survival times with disseminated disease have been reported.

Indications and Contraindications

Although generally benign, CBT may metastasize, and their growth is relentless. Moreover, large tumors frequently involve the vagus and hypoglossal nerves and thereby increase the risk of peri-operative injury to cranial nerves. Thus, early diagnosis of small tumors in the presence of nonatherosclerotic carotid vessels facilitates definitive surgical treatment with the least potential for significant morbidity and the best possibility for cure. Overall, surgical resection is recommended for all patients. However, observation may be appropriate for elderly patients in poor health with asymptomatic tumors or perhaps for those patients with bilateral tumors who develop cranial nerve dysfunction after resection of one tumor.

Pre-operative Assessment

While duplex scanning is helpful in detecting the presence of a CBT, a combination of CT scanning followed by angiography is our recommended set of imaging studies, both for diagnosis and pre-operative planning. CT scanning is especially helpful in determining the size and extent of the tumor and can identify the presence of contralateral tumors. Contrast angiography generally shows a highly vascular mass at the carotid bifurcation and is especially helpful for pre-operative planning in the treatment of tumors that are larger than 5 cm. Specifically, test occlusion of the common carotid artery may predict the need for shunting, should carotid clamping be necessary, or the need for direct revascularization, if resection of the internal carotid is required.

Moreover, in rare instances when direct reconstruction of the internal carotid artery may not be feasible, initial external carotidinternal carotid (EC-IC) bypass followed by internal carotid artery occlusion may provide a reasonable option for the management of the difficult tumor. In general, the presence of significant carotid atherosclerotic disease is unusual in this patient population.

Moreover, in rare instances when direct reconstruction of the internal carotid artery may not be feasible, initial external carotidinternal carotid (EC-IC) bypass followed by internal carotid artery occlusion may provide a reasonable option for the management of the difficult tumor. In general, the presence of significant carotid atherosclerotic disease is unusual in this patient population.

In some institutions, pre-operative tumor embolization has been advocated in order to minimize operative blood loss, particularly for carotid body tumors greater than 3 to 5 cm in diameter. However, we have generally not found this to be an especially helpful adjunct. Embolization may itself carry some risk of an adverse event; blood loss is often not significantly reduced, and a peritumor inflammatory response due to the embolization procedure may paradoxically increase the difficulty associated with tumor dissection.

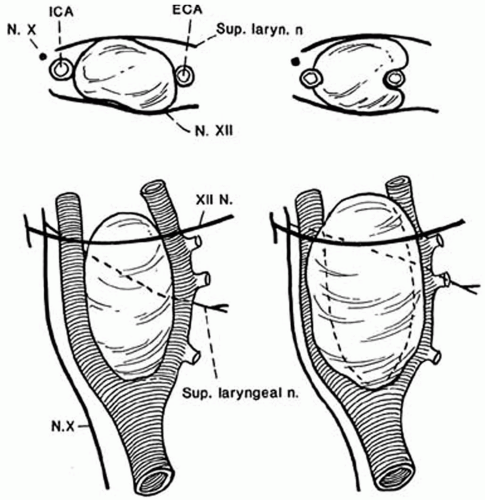

Anatomic Considerations

The Shamblin classification remains a useful approach for categorizing the extent of the CBT and does provide some insight into the overall risk of associated cranial nerve deficit and the potential necessity for reconstruction or ligation of the extracranial carotid artery (Fig. 31-2). Using CT images, the Shamblin tumor type is classified as Type I: small tumor, easily resectable; Type II: large tumor, adherent to and partially encircling the carotid vessels; or Type III: tumor completely surrounding the internal carotid artery and potentially encasing adjacent cranial nerves. In general, tumors greater than 4 cm in diameter are most commonly Shamblin Type 2 or 3. As a final note, the primary blood supply for CBT arises from the external carotid artery and its branches. These highly vascular tumors carry more blood flow per gram than any other tumor.

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|