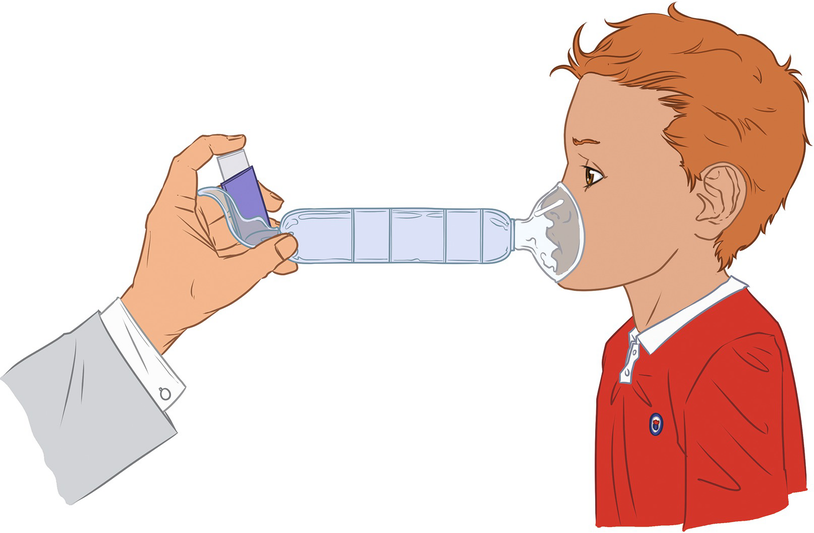

Inhalation technique using salbutamol (MDI) and spacer with mouthpiece

MDI and spacer with mask inhalation technique. The spacer must be placed in the child’s face in such a way that it covers mouth and nose. The MDI device is shaken well and then activated, waiting for the child’s spontaneous breathing, at least three times.

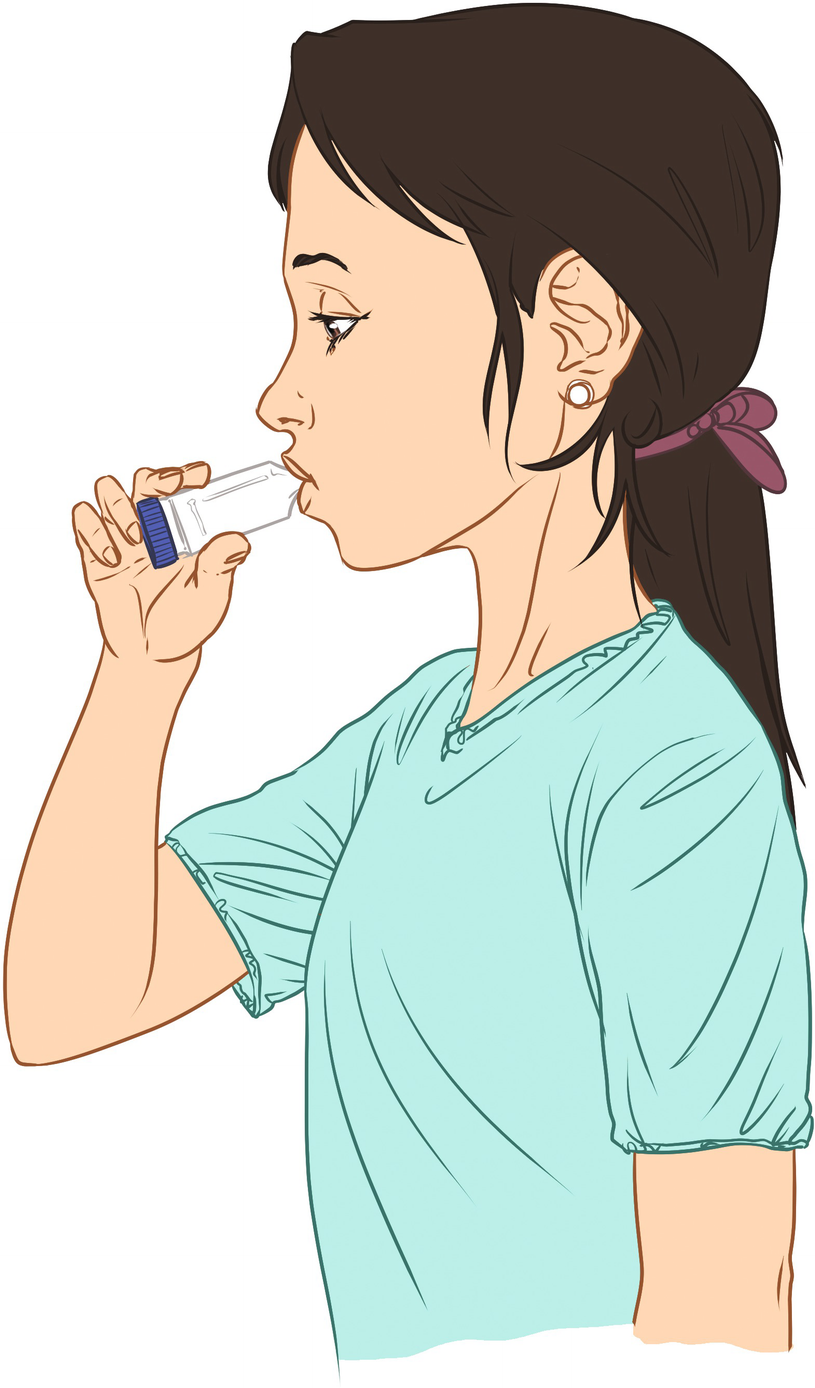

Inhalation technique with a DPI. The dry powder inhaler (DPI) must be active according to the manufacturer’s recommendation, because its use technique may vary. A deep inhalation is done with the device placed in the mouth, then the breath must be held, followed by a normal exhalation. It is recommended to rinse the mouth after the inhalation.

Pharmacological Treatment

Treatment of Acute Asthma Exacerbations

Evaluation of asthma exacerbation

Parameter | Mild | Moderate | Severe |

|---|---|---|---|

Dyspnea | When walking; it can also be present when lying down | When speaking, prefers to be sitting Crying low and short in infants, has difficulties when feeding. | When resting, the infant cannot be fed |

Speaks in | Long sentences | Short sentences | Isolated words |

Consciousness | Patient can be agitated | Usually agitated | Usually agitated |

Respiratory frequency | Increased | Increased | Very increased |

<2 min: <60 | |||

2–12 min: <50 | |||

1–5 to <40 | |||

6–8 to <30 | |||

Heart rate | <100 bpm | 100–120 bpm | >120 bpm |

2–12 min: <160 bpm | |||

1–2 to <120 bpm | |||

2–8 to <110 bpm | |||

Accessory muscles | No use, generally | Yes | Yes |

Wheezing | Moderated: only at the end of exhalation | Intense | Usually intense |

Pulsus paradoxus | Absent: <10 mmHg | May be 10–25 mmHg | Present 20–40 mmHg |

PEF post β2a | >80% | 60–80% | <60% |

SaO2 (FiO2: 21%) | >95% | 91–95% | <90% |

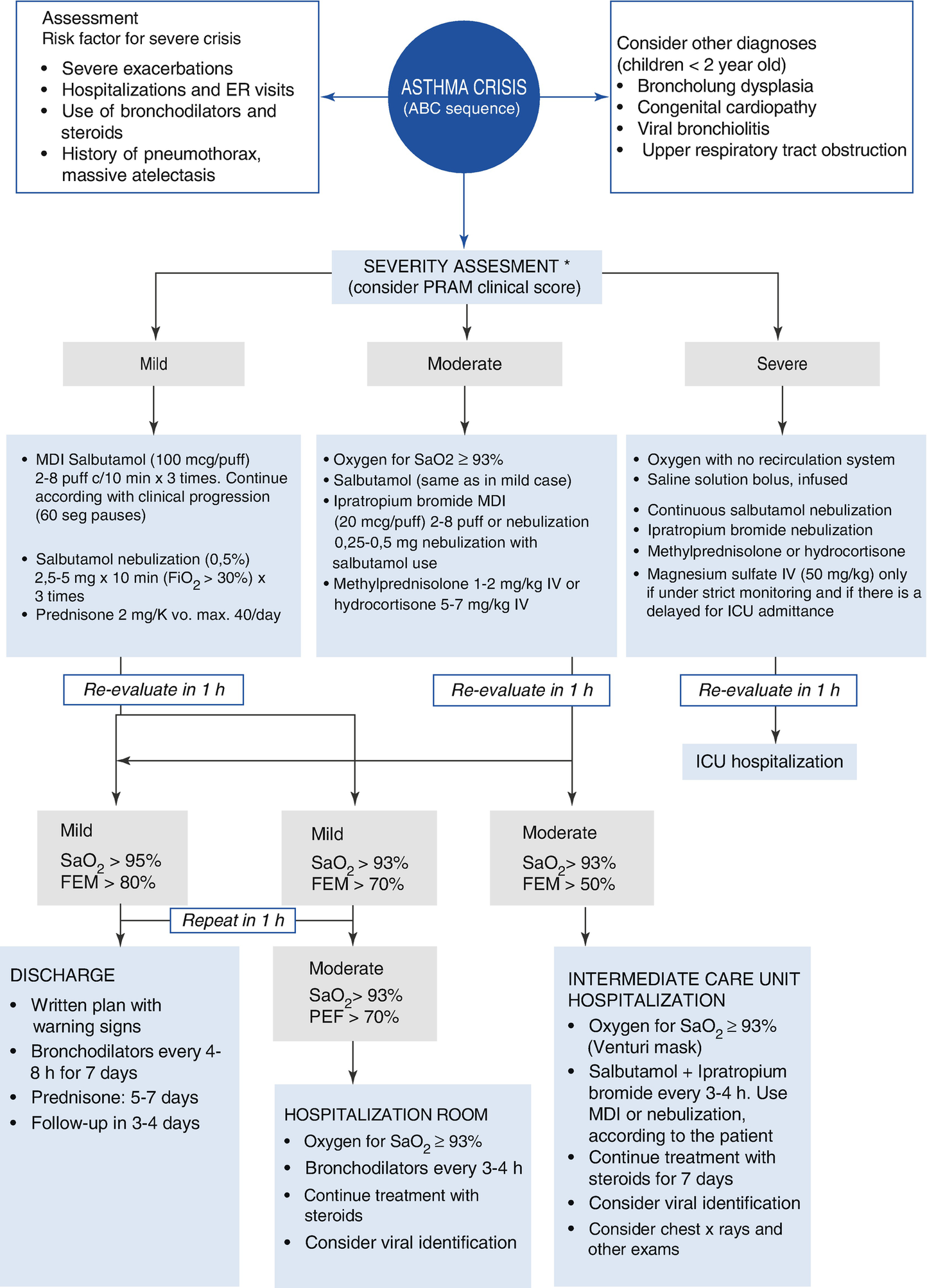

Treatment algorithm for asthma crises

Oxygen

The administration of oxygen is the easiest and most efficient intervention to reduce hypoxemia during an acute asthma exacerbation. It can completely correct respiratory insufficiency in most patients, only excepting those with severe hypoventilation. Oxygen is administered through a nasal tube, non-rebreathing mask, or Venturi mask system, according to the need and tolerance of each patient.

Medical oxygen is a dry gas that must be humidified to avoid problems related to drying of the respiratory mucosa when high flow is used. The objective of oxygen administration is to avoid hypoxemia, which can be indirectly measured through pulse oximetry (SpO2), aiming for a value >93% (Evidence C). Those patients requiring supplementary oxygen at the time they are evaluated in the emergency room should be hospitalized. Patients with a moderate score or those who have respiratory distress when they seek medical attention should be evaluated again after 24–48 h, even if they responded adequately to the treatment used in the first hours of the medical visit, especially those patients who are difficult to follow up, have poor treatment adherence, or have a previous history of hospitalizations caused by asthma.

Bronchodilators

Short-acting beta-2 agonists (SABA) inhaled bronchodilators, such as salbutamol, fenoterol, and terbutaline, are the first-line treatments for acute asthma exacerbation (Evidence A). Administration of inhaled salbutamol (MDI) with a spacer with valve is just as effective as the nebulization of the same drug, and saves time and reduces the need of professional supervision in the emergency room. Additionally, the use of inhaled salbutamol with a spacer causes fewer adverse effects. Salbutamol should be administered proportionally to the seriousness of the crisis, and the clinical effect should be closely monitored and recorded. It is recommended to perform two to eight inhalations each time, and repeat them during the first hour of treatment until the desired clinical response has been achieved. Salbutamol administered in frequent intervals is more efficient, although it is important to assess for adverse effects, which also allows us to guide the adequate doses and frequency for each patient. For those patients with high oxygen requirements (FiO2 > 30%) the administration of nebulized bronchodilators should be considered. In these cases, it is recommended to use a dose of 2.5–5 mg (standard dose) each time, using the same principle of dosage titling. For serious crises, continuous nebulization has been described as a more effective way of bronchodilator treatment until a clinical response is achieved.

Anticholinergic bronchodilators (ipratropium bromide) in repeated doses add their effect to those of beta-2 agonists in the treatment of moderate and severe exacerbations (Evidence B). Combination with SABA has been associated with a lower risk of hospitalization. They are available combined for both inhalation and nebulization.

Steroids

Systemic steroids are the preferred antiinflammatory treatment for acute asthma exacerbations (Evidence A). Early use is recommended to reduce the risk of hospitalization. The treatment should be administered over 3 to 5 days, which in most cases is enough to control the crisis. Oral administration of steroids is as effective as their intravenous administration, and therefore the oral option is recommended for its availability and reduced cost. The only exceptions are those patients who must receive the intravenous drug because their condition is serious. Every patient with moderate or severe asthma exacerbations must receive systemic steroids within the first hour of treatment in the emergency room. Those patients with a mild crisis and who have used bronchodilators, but with a poor response, should also receive steroids as a central part of their treatment.

The administration of inhaled or nebulized steroids for the acute asthma crisis is still being evaluated when they are used in combination with bronchodilators. Systematic reviews have shown that the therapeutic effect would be comparable to using oral steroids; nevertheless, its use must be part of a supervised treatment plan to avoid confusion or abuse of the drug. Currently, there is no strong recommendation about this issue.

Other Therapies

Nebulized magnesium sulfate could reduce the hospitalization risk in patients who have serious acute asthma exacerbations that do not respond to bronchodilators. There is no strong evidence to recommend its use in mild to moderate crises (Evidence A). IV magnesium sulfate may be considered for serious asthma crises, when the patient is hospitalized in the intensive care unit (Evidence B), as this medication must be supervised by specialists in intensive care.

Aminophylline and salbutamol can be used in the management of severe and acute exacerbations, but under strict supervision in critical patients as an additional therapy. The effects of both treatments have been compared, and no differences have been found in their clinical efficacy (Evidence B).

In severe and acute exacerbations, helium in different concentrations mixed with oxygen can be used to gain some time while other measures are being placed to avoid the progression of respiratory distress. Even so, there is no high-quality evidence to recommend its use (Evidence B).

There is no clinical evidence to use IV leukotriene inhibitors in the treatment of acute asthma exacerbations.

There is no evidence to recommend the use of chest physiotherapy during acute asthma exacerbations, and some maneuvers, such as chest percussion or forced compressions, are contraindicated.

In the same way, antibiotics , as well as antihistamines, sedatives, and mucolytic drugs, have no role in the treatment and their use is discouraged.

Mechanical Ventilation

Mechanical ventilation is an alternative in patients with a severe asthma exacerbation in respiratory failure. Indications for its use are based on clinical criteria, although there are absolute indications, such as severe hypoxemia, compromise of consciousness, and cardiopulmonary failure. Preliminary evidence suggests the use of noninvasive ventilation for patients who can cooperate to avoid development of muscular fatigue. This therapy is not an alternative to invasive ventilation; it is only a previous step aiming to avoid endotracheal intubation. In those patients requiring ventilation support, pressure-limited delivery and low flow volumes should be used. The suggested baseline parameters are tidal volume (TV) 8–12 ml/kg, inspiratory time (TI) 0.7–1.5 s, and maximum inspiratory pressure (MIP) 40 cm H2O. Alveolar ventilation should be optimized with an increase in the time constant, but at the same time favoring prolonged exhalation times to avoid auto-positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP).

Mechanical ventilation in patients with asthma exacerbation is a therapy that can trigger some complications arising from the high pressures required, such as barotrauma and hemodynamic alterations. If it is necessary to sedate patients undergoing mechanical ventilation, use of morphine and muscle blockers is discouraged.

Hospitalization Criteria

Progressive dyspnea and/or increased work of breathing

Signs and symptoms of moderate or severe exacerbations

Poor response to treatment after 2 h

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree