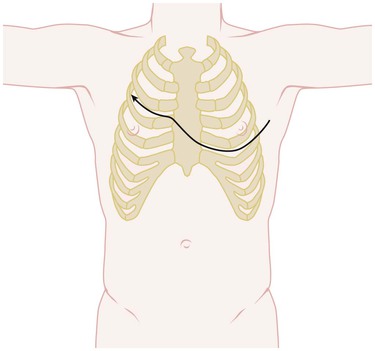

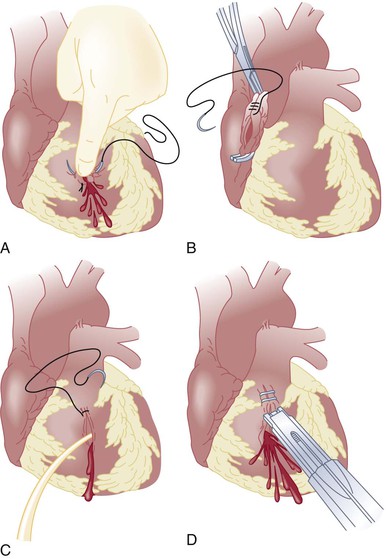

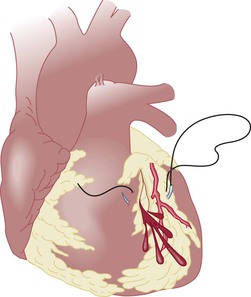

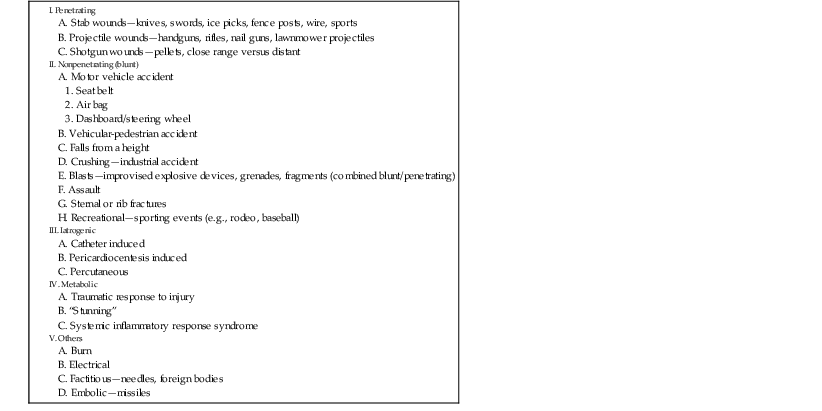

Peter I. Tsai, Matthew J. Wall Jr.,, Kenneth L. Mattox Thoracic trauma is responsible for 25% of the deaths from vehicular accidents, 10% to 70% of which may have been the result of blunt cardiac rupture. Twelve lethal injuries from thoracic trauma include airway obstruction, tension pneumothorax, open pneumothorax, massive hemothorax, flail chest, thoracic aortic disruption, cardiac tamponade, blunt cardiac injury, tracheobronchial disruption, traumatic diaphragmatic tear, esophageal disruption, and pulmonary contusion.1 The overall mortality associated with penetrating cardiac trauma has not changed significantly in the major trauma centers, thus suggesting such trauma to be highly lethal with relatively few victims surviving long enough to reach the hospital. Our own institutional data demonstrate that transport times of less than 5 minutes with up to 9 minutes of prehospital cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) and successful endotracheal intubation are positive factors for survival when the patient suffers a pulseless cardiac injury in the field. This also correlates with a higher survival rate if emergency thoracotomy is performed to address the injuries (75%) versus a lower survival rate (25%) if emergency thoracotomy is to be performed in the emergency department, an observation suggestive of the dire nature of the injury.2 Traumatic heart disease can be categorized on the basis of the mechanism of injury (Table 72-1). Knowledge of the various types of cardiac injury, the methods available to facilitate rapid diagnosis, and familiarity with the techniques for surgical repair are no longer an academic exercise but a life saving necessity.3 This chapter deals primarily with the features, evaluation, and treatment of penetrating, nonpenetrating, and miscellaneous cardiac injuries. TABLE 72-1 Causes of Traumatic Heart Diseases Penetrating trauma is the most common cause of significant cardiac injury seen in the hospital setting, with the predominant cause being firearms and knives.4,5 The location of injury to the heart often correlates with the location of injury on the chest wall. Because of their anterior location, the anatomic chambers at greatest risk for injury are the right and left ventricles. Our group to date has published the most comprehensive review consisting of 711 patients with penetrating cardiac trauma—54% by stab wounds versus 42% by gunshot wounds. Both the right and left ventricles were each injured in 40% of the cases, the right atrium in 24%, and the left atrium in 3%. A third of the cardiac injuries involved multiple cardiac structures.4 Significant complex cardiac injuries involved the coronary arteries (5%), valvular apparatus (mitral) (0.3%), and intracardiac fistulas (i.e., ventricular septal defects [VSDs]) (2%). Only 2% of patients surviving the initial injury and undergoing surgery required reoperation for a residual defect, and most of these repairs were performed on a semielective basis.4 Thus, most injuries involve the myocardium and are readily managed by a general/trauma or acute care surgeon. Wounds involving the epigastrium and precordium should raise suspicion for cardiac injury. Stab wounds are characterized by a more predictable path of injury than gunshot wounds are. Patients with cardiac injury can have a clinical spectrum ranging from full cardiac arrest with no vital signs to asymptomatic status with normal vital signs. Up to 80% of stab wounds that injure the heart eventually result in tamponade. The weapon injures the pericardium and heart, but as the weapon is removed, the pericardium may not allow the blood to escape. As pericardial fluid accumulates, a decrease in ventricular filling occurs and leads to a decrease in stroke volume. A compensatory rise in catecholamines causes tachycardia and increased right-heart filling pressure. The limits of distensibility are reached as the pericardium is filled with blood, and the septum shifts toward the left side, thereby further compromising left ventricular function. If this cycle persists, ventricular output can continue to deteriorate and result in irreversible shock. As little as 60 to 100 mL of blood in the pericardial sac can produce the clinical picture of tamponade.6 The rate of accumulation depends on the location of the wound. Because it has a thicker wall, wounds involving the right ventricle seal themselves more readily than do wounds involving the right atrium. Patients with injuries penetrating the coronary arteries have a rapid onset of tamponade combined with cardiac ischemia. The classic findings of the Beck triad (muffled heart sounds, hypotension, and distended neck veins) are seen in only 10% of trauma patients. Pulsus paradoxus (a substantial fall in systolic blood pressure during inspiration) and the Kussmaul sign (increase in jugular venous distention on inspiration) may be present but are not reliable signs. A valuable and reproducible sign of pericardial tamponade is narrowing of the pulse pressure. In contrast to stab wounds, gunshot wounds involving the heart are more frequently associated with hemorrhage than with tamponade. Twenty percent of gunshot wounds to the heart are manifested as tamponade. With firearms, the kinetic energy is greater and wounds to the heart and pericardium are frequently larger. Thus these patients are more often initially seen with exsanguination into a pleural cavity and arrest. Evaluation of suspected heart injury differs, depending on whether the patient is clinically stable or in extremis. The diagnosis of heart injury requires a high index of suspicion. On initial arrival at the emergency center, airway, breathing, and circulation (ABCs) according to the advanced trauma life support protocol are evaluated and established.7 Intravenous access is obtained, and blood is typed and crossmatched. The patient undergoes chest radiography, followed by focused abdominal sonography for trauma (FAST),8 and can be examined for the Beck triad of muffled heart sounds, hypotension, and distended neck veins, as well as for pulsus paradoxus and the Kussmaul sign. These findings suggest cardiac injury but are present in only 10% of patients with cardiac tamponade. If the FAST examination demonstrates pericardial fluid in an unstable patient (systemic blood pressure <90 mm Hg), transfer to the operating room to address the injury is recommended. Patients in extremis often require emergency thoracotomy for resuscitation. Clear indications for emergency department thoracotomy by surgical personnel include the following9: If vital signs are regained after resuscitative thoracotomy, the patient is transferred to the operating room for definitive repair. Patients with confirmed pericardial fluid by FAST along with normal vital signs (systemic blood pressure >90 mm Hg) may undergo a thorough evaluation to identify associated injuries before open exploration to exclude cardiac injury. In the absence of known causes of pericardial fluid (malignant pericardial effusion), a missed cardiac injury can lead to delayed bleeding, deterioration, or death. Surgeons are increasingly performing ultrasonography for thoracic trauma, similar to the use of ultrasonography for blunt abdominal trauma. Ultrasonography is safe, portable, and expeditious and can be repeated as indicated. If performed by a trained surgeon, the FAST examination has a sensitivity of 97% to 100%.8 As the use of FAST evolves, the most universally agreed indication is evaluation for pericardial blood. Chest radiography is nonspecific, but it can identify hemothorax or pneumothorax. Other possibly indicated examinations include computed tomography (CT) for determination of the trajectory, endoscopy for detection of esophageal injury, and bronchoscopy for identification of airway injury (see Chapters 15 to 18). Definitive treatment involves surgical exposure through an anterior thoracotomy or median sternotomy. The goals of treatment are relief of tamponade and control of hemorrhage. Concomitantly, correction of acidosis and hypothermia and reestablishment of effective coronary perfusion are addressed by appropriate resuscitation. Exposure of the heart is accomplished via a left anterolateral thoracotomy (Fig. 72-1), which allows access to the pericardium and heart and exposure for aortic crossclamping if necessary. This incision can be extended across the sternum to gain access to the right side of the chest and for better exposure of the right atrium or right ventricle. Once the left pleural space is entered, the lung is retracted medially to expose the descending thoracic aorta for crossclamping. The amount of blood present in the left side of the chest indicates whether one is dealing with hemorrhage or tamponade. The pericardium anterior to the phrenic nerve is opened, injuries are identified rapidly, and repair is performed. In selected cases, particularly stab wounds involving the precordium, median sternotomy can be performed. This incision allows excellent exposure to the anterior structures of the heart, but difficulty with access to the posterior mediastinal structures and descending thoracic aorta for crossclamping may be encountered. Cardiorrhaphy should be performed carefully. Poor technique can result in enlargement of the lacerations or injury to the coronary arteries. If the initial treating physician is uncomfortable with the suturing technique, digital pressure can be applied until a more experienced surgeon arrives. Other techniques that have been described include the use of a Foley balloon catheter and a skin stapler (Fig. 72-2). Injuries adjacent to the coronary arteries can be managed by placing the sutures deep to the artery (Fig. 72-3). Mechanical support is not often required in the acute setting.

Traumatic Heart Disease

Incidence

Penetrating Cardiac Injury

Cause

Clinical Features and Pathophysiology

Evaluation

Treatment

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Traumatic Heart Disease

72