INDICATIONS/CONTRAINDICATIONS

The age distribution of patients with achalasia is a bell-shaped curve ranging from the very young to those of advanced age. The peak age for clinical presentation is 30 to 40 years. There is no cure for achalasia, and there are limited treatment options. The first principle of care, therefore, is to ensure that any treatment for patients with achalasia fits into a lifelong plan for their care. This is especially true for patients presenting at a younger age.

The indications for management of patients with achalasia include dysphagia leading to weight loss, prominent regurgitation especially with associated aspiration pneumonia, and pain from spasm. In general, despite its effectiveness, open surgery is no longer considered the best first-line therapy for achalasia. Treatment plans should proceed from less to more invasive methods. Laparoscopic esophagomyotomy has emerged as the leading primary treatment, especially in younger patients. Still, there is a role for open surgery.

Indications for open myotomy include the following.

Failure of prior laparoscopic esophagomyotomy, especially if the results were initially favorable

Failure of prior laparoscopic esophagomyotomy, especially if the results were initially favorable

Failure of medical therapy such as botulinum toxin injections or pneumostatic dilatation

Failure of medical therapy such as botulinum toxin injections or pneumostatic dilatation

Patients whose esophagus has been perforated during nonopen treatment methods

Patients whose esophagus has been perforated during nonopen treatment methods

Patients who are not candidates for laparoscopic methods due to adhesions or prior surgeries

Patients who are not candidates for laparoscopic methods due to adhesions or prior surgeries

Associated intrathoracic or esophageal pathology such as diverticular disease or associated ipsilateral lung pathology requiring surgery

Associated intrathoracic or esophageal pathology such as diverticular disease or associated ipsilateral lung pathology requiring surgery

Vigorous achalasia

Vigorous achalasia

An irreparable esophagus secondary to size, tortuosity, or injury

An irreparable esophagus secondary to size, tortuosity, or injury

Contraindications for open surgery include the following.

Patient is not a candidate for open surgery due to the risk of surgery from comorbidities

Patient is not a candidate for open surgery due to the risk of surgery from comorbidities

Young patients who have not been evaluated for laparoscopic esophagomyotomy

Young patients who have not been evaluated for laparoscopic esophagomyotomy

Indications for esophageal replacement include the following.

Failed prior surgeries for esophagomyotomy with scarring, stricture, and adhesions

Failed prior surgeries for esophagomyotomy with scarring, stricture, and adhesions

Markedly dilated esophagus (>6 cm diameter), also referred to as megaesophagus, especially when associated with tortuosity

Markedly dilated esophagus (>6 cm diameter), also referred to as megaesophagus, especially when associated with tortuosity

PREOPERATIVE PLANNING

PREOPERATIVE PLANNING

Preoperative preparation involves confirming the diagnosis of achalasia, ruling out or identifying any associated conditions, assessing overall gastrointestinal motility, and assessing the patient’s risk for thoracotomy.

Manometry remains the gold standard for diagnosing achalasia. If this is not available or not tolerated by the patient, video esophagography by an experienced radiologist serves well to confirm the clinical suspicion of achalasia. A standard contrast swallow is less accurate but is sometimes clear in cases of dilated esophagus with a classic bird’s beak narrowing of the lower esophagus at the esophagogastric junction.

Associated esophageal conditions that should be looked for include evidence for spasm, as seen with vigorous achalasia, or diverticular disease. Flexible esophagogastroscopy should be performed to rule out an occult esophageal malignancy presenting as pseudoachalasia. Finally, any other intrathoracic pathology that might need to be managed or evaluated at thoracotomy should be identified before surgery. Computed tomography, though not needed routinely before transthoracic esophagomyotomy, will best define any ipsilateral thoracic pathology if it is suspected.

Rarely a patient is suspected of having achalasia clinically, who in fact has global, severe, gastrointestinal hypomotility. The patient’s dysphagia and regurgitation, a product of pan-gastrointestinal lack of inertia, are falsely interpreted as a primary esophageal disorder. Proceeding with esophagomyotomy in these patients does not solve their clinical problem.

Patients should undergo standard preoperative workup for thoracotomy. The need for a more detailed evaluation of cardiorespiratory status, including detailed cardiac or pulmonary function, depends on a patient’s clinical history and physical findings.

SURGERY

SURGERY

The objectives of transthoracic esophagomyotomy are to relieve lower esophageal obstruction by myotomy, address any associated esophageal pathology if present, and prevent or minimize postoperative gastroesophageal reflux.4 The following procedures will be discussed: (1) esophagomyotomy (Heller procedure), (2) esophagomyotomy with partial fundoplication (“modified Heller procedure”), (3) extended esophagomyotomy for vigorous achalasia, (4) reoperative esophagomyotomy, and (5) esophageal replacement.

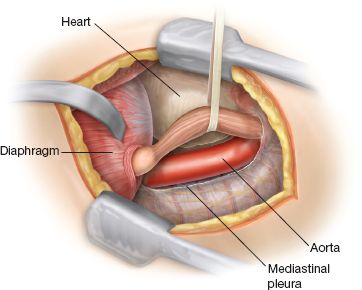

Transthoracic Esophagomyotomy

Double-lumen general endotracheal anesthesia is used. Special attention must be directed toward protection against aspiration during intubation, given the potential for regurgitation of retained esophageal contents in achalasia patients. A nasogastric tube is placed prior to patient positioning to empty the esophagus, facilitate esophageal mobilization, and for postoperative esophagogastric decompression if needed. Patients are then positioned in the right lateral decubitus position. A left lateral thoracotomy through the sixth, seventh, or eighth intercostal space is used. The specific interspace should be individually selected based on the level of the left side of the diaphragm so that optimal exposure of the lower esophagus is obtained. If the incision is too low, the left hemidiaphragm obstructs the operative field. If it is too high, it is extremely difficult to see or reach the lower chest to complete the surgery. The ideal interspace should open just over the dome of the ipsilateral hemidiaphragm (Fig. 15.1). Ellis et al.3,5 are credited with championing the method of esophagomyotomy that is limited to the distal esophagus. The distal esophagus is circumferentially mobilized taking care not to injure the vagus nerves or to disrupt the esophageal hiatal attachments. An encircling 0.25-inch Penrose drain works well to lift the lower esophagus up from the mediastinum. A longitudinal myotomy is performed down to the mucosa that characteristically pouts out (Fig. 15.2). The myotomy extends distally just across the esophagogastric junction onto the stomach for a length of 1 cm or less. Proximally, it is continued for a 5 to 7 cm total length. The cut edges of the muscle are further dissected back to widely free the mucosal lumen and to prevent rehealing of the cut muscle (Fig. 15.3). Adding additional procedures, such as vagotomy, gastric drainage, or fundoplication, according to Ellis,6 “merely complicates an otherwise simple operation.”

The technique of open myotomy that we prefer uses blunt-tipped Metzenbaum scissors to divide the muscle down to the mucosa. This yields a very controlled myotomy with easy muscle layer identification and a minimal chance of mucosal damage. Once the mucosa is identified the myotomy is easily and rapidly extended in either direction. Other methods include using a straight or hooked cautery, or a long-handed knife to divide the muscle. If a knife is used, passing a midsized bougie into the esophagus first can serve as an “anvil” upon which to cut with greater control.

Thoracotomy closure with chest tube drainage is routine.

Figure 15.1 Operative exposure. The narrowed distal esophagus is mobilized in preparation for myotomy.