Figure 31.1

Thymus anatomy. Because there is a debate concerning the role of thymectomy in myasthenia gravis and, if indicated, what operative technique best accomplishes this goal, it is important to understand the anatomy of the thymus. This knowledge is critical to both choosing an operative procedure and accomplishing the goal of removing all thymic tissue that may be contributing to the myasthenia, as well as to understanding comparative studies of different techniques. The thymus in toto is not a separate encapsulated organ but rather a collection of large and small thymic rests, with one predominant centrally located collection. Detailed surgical–anatomic studies have demonstrated that the thymus usually consists of multiple lobes in both the neck and mediastinum, often separately encapsulated, and that these may not be contiguous. In addition, unencapsulated lobules of thymus and microscopic foci of thymus may be distributed widely in the pretracheal and anterior mediastinal fat from the level of the thyroid to the diaphragm, behind the thyroid to as high as the hyoid cartilage, and bilaterally beyond each phrenic nerve. Microscopic foci of thymus also have been found in subcarinal fat, as well in separate aortopulmonary (A-P) window tissue and in the pleural and pericardial tissue planes. Critical to complete and safe execution of the procedure is a thorough knowledge of the course of the phrenic and recurrent laryngeal nerves in the chest and neck. Given the symptoms of myasthenia, injury to any of these nerves may cause significant short- and long-term consequences

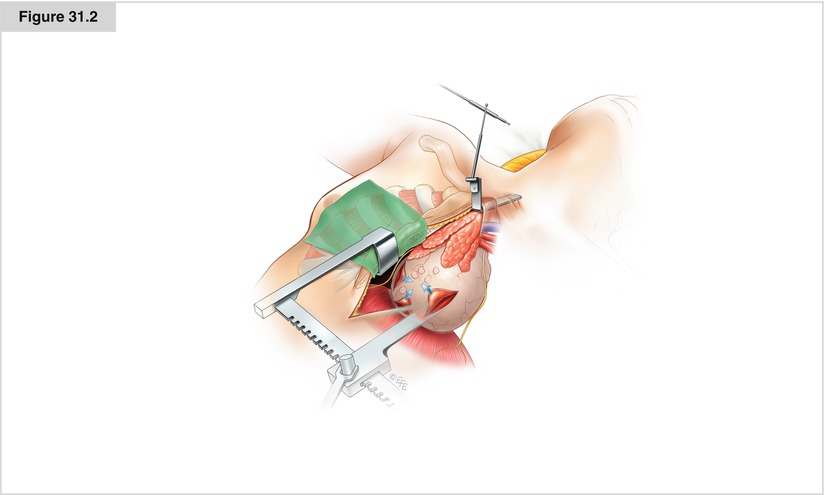

Figure 31.2

Sternotomy approach and initial dissection. Single-lumen intubation may be used; low tidal volumes and moistened large laparotomy pads are used to retract the lungs from the field. Median sternotomy is performed via a skin incision centered in the lower midline so patients can wear V-neck dresses or open-collar shirts. In women, the incision usually can be placed below the cleavage line, and the dissection begins by mobilizing the mammary tissue on top of the greater pectoral muscle to allow the incision to be mobile. A small pediatric sternal retractor is used for the sternal retraction, and a superior thin-blade (Thompson) retractor (Thompson Surgical Instruments, Traverse City, MI) is placed on the table and used to improve visualization of the neck. The dissection is started by releasing the mediastianal pleura from the sternal edges with all fat intact up to the internal mammary artery and vein from the first rib to the diaphragm. Small vessels from the internal mammary artery and vein may require clipping; the vessels are kept intact for future use if needed. Both phrenic nerves are visualized in their entire course, and pericardial retraction sutures are placed medial to the nerves on each side to help retract the nerves into the field during dissection of each respective side. En block resection of the thymic complex then begins with sharp dissection at the pericardiophrenic sulcus bilaterally and at the diaphragm. Sharp dissection may be used to remove all the mediastinal tissue and diaphragm in a single sheet starting from the diaphragm and proceeding cephalad. With sharp dissection, a fine plane can be developed and all tissue removed from the pericardium, which has been found to encompass rests of thymic tissue. As dissection proceeds cephalad on each side, the en block material is released from the phrenic nerves bilaterally under direct vision. Electrocautery is discouraged, and small vessels extending medially from the phrenic nerve are clipped carefully. Care should be taken to preserve the phrenic blood supply, as the nerves may become compromised if devascularized

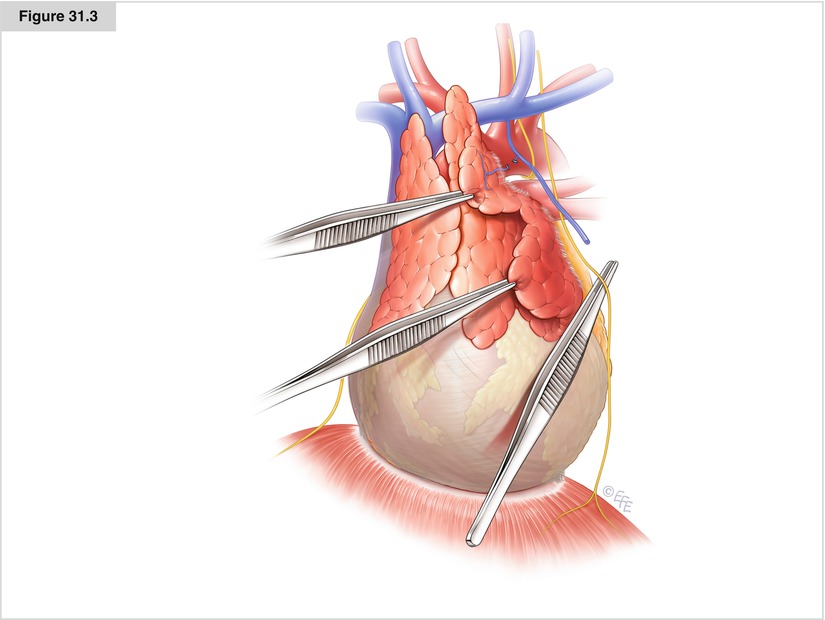

Figure 31.3

Dissection of the phrenic nerves, A-P window, and innominate vein. En block dissection continues by releasing any thymic tissue adjacent or lateral to the phrenic nerves. On the left side, thymic tissue frequently has a tongue of tissue extending under the phrenic toward the A-P window. This tissue is removed en bloc with the primary specimen by carefully elevating the phrenic nerve in this section and moving all the thymic tissue and fat medially. After this has been performed, proper dissection of the A-P window is accomplished, and this tissue is sent separately. Care must be taken in this region to avoid injury to the recurrent laryngeal nerve as it leaves the vagal sheath and passes under and around the aortic arch. Dissection continues cephalad, and all tissue medial to the phrenic nerves, including the thymo-fatty tissue lying in the sulcus between the cava and the aorta, is included in the specimen. The cephalad dissection, just medial to the phrenic nerves, leads to the junctions of the internal mammary veins and innominate veins bilaterally. Thymo-fatty tissue frequently lies in the posterior recess of the veins in this area and should be included in the specimen. Next, the thymus is separated from the innominate vein by sharp dissection, and the thymic veins, both inferiorly and superiorly, are clipped and divided. Any tissue lying posterior to the vein and anterior to the arterial branches of the aorta should be included in the specimen. The mediastinal dissection above the innominate artery is completed by identifying the carotid arteries bilaterally and the anterior trachea and by removing all the thymo-fatty tissue in this region. If one keeps the dissection plane anterior to the trachea and medial to the carotid sheaths, direct injury or traction injury to the recurrent nerves should be avoided

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree