Transmetatarsal Amputation

ANNA ELIASSEN and DAWN M. COLEMAN

Presentation

A 70-year-old man with a history of hypertension, hyperlipidemia, insulin-dependent diabetes, and tobacco abuse presents with nonhealing, painful lower extremity tissue loss. He describes ulceration affecting the distal aspects of his left toes of approximately 4-month duration despite careful wound care. He denies history of antecedent trauma. He denies fever. Exam reveals palpable femoral and absent dorsalis pedis (DP) pulses bilaterally. There is a dry eschar affecting all toes on the left with demarcated tissue that appears healthy just proximal to his metatarsals (Fig. 1).

FIGURE 1 Pedal photograph revealing dry eschar affecting all toes and demarcation of healthy proximal tissue.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis for nonhealing lower extremity ulcer and tissue loss includes ischemia (i.e., atherosclerosis and arteritis), venous insufficiency, diabetic neuropathy, pressure, and malignancy. Additionally, it is critical that any associated necrotizing soft tissue infection (i.e., wet gangrene) complicating a lower extremity ulcer is promptly recognized such that treatment with broad-spectrum parenteral antibiotics and surgical source control are not delayed.

Ulcer location and appearance will help identify wound etiology. Ischemic ulcers often accompany symptoms of rest pain. These ulcers are generally located over prominent bony areas that may result in pressure points for skin shear (i.e., toe tips, phalangeal heads, lateral malleolus, etc.) and typically appear even and sharply demarcated with punched-out wound margins. Tissue necrosis, cellulitis, and dry necrotic eschar may be present. Additionally, the surrounding skin is often blanched or purpuric, appearing at times shiny or “tight” with associated hair loss of the foot and ankle.

Ulcers of venous insufficiency typically spare the feet and toes, but rather occupy a location between the knee and ankle—most commonly these wounds affect the medial malleolus, but the lateral malleolus can also be affected. Surrounding skin will likely demonstrate additional findings consistent with advanced chronic venous insufficiency including eczematous changes, scaling, weeping, crusting, dermatitis, pruritus, hyperpigmentation, or lipodermatosclerosis. Diabetic neuropathic ulcers result from multiple factors that include neuropathy, autonomic dysfunction, and microvascular insufficiency. These ulcers are located at areas of repeated pressure-induced trauma (i.e., plantar metatarsal heads or dorsal interphalangeal joints) and are associated with an overgrowth of hyperkeratotic tissue (i.e., corn or callus) and signs of neuropathy on physical exam. These ulcers demonstrate undermined borders.

The patient in the above scenario presents with multiple risk factors for atherosclerotic occlusive disease. Additionally, the lesion location is highly suspicious for ischemic ulceration.

Workup

Additional clinical history should elicit symptoms of claudication or rest pain, lower extremity venous insufficiency (i.e., heaviness, aching, swelling), and diabetic neuropathy. Previous wounds and attempts at wound therapy should be documented. A complete lower extremity vascular exam that assesses for capillary refill, skin atrophy, hypertrophic nails, and hair loss in addition to pulses is necessary. Additionally, the wounds should be further qualified, specifically noting location, dimensions, presence of exposed tendon or bone, appearance of wound bed, and any associated cellulitis, drainage, and induration.

Noninvasive vascular lab studies including ankle-brachial index (ABI), duplex ultrasound, segmental blood pressures, and plethysmography will help confirm ischemic etiology and localize level of disease. In diabetics, the tibial vessels are often heavily calcified lending to noncompressibility and artificial elevation of the ABI. In these clinical situations, toe-brachial index (TBI) should be considered. Blood should be sent to assess for any leukocytosis; additionally, inflammatory markers (i.e., C-reactive protein) may be elevated in the setting of osteomyelitis. If there is any concern for bone infection, a bone scan or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may be considered for radiographic confirmation. Finally, computed tomography (CT) angiography and traditional angiogram are both adjuncts that will further identify arterial anatomy; angiography offers the benefit of simultaneous intervention if clinically appropriate.

On clinical exam, this patient has no sign of exposed bone, exposed tendon, or active cellulitis. While the toes have dry gangrene, the plantar surface is intact. There is hair loss about the ankle, palpable bilateral femoral pulses, and nonpalpable pedal pulses. Bilateral ABIs are 1.2, but tibial vessels are noted to be noncompressible. The right great toe has a TBI = 0.5, and the left DP and posterior tibial (PT) arterial waveforms are biphasic. MRI reveals osteomyelitis affecting the distal toes. Diagnostic arteriogram reveals preserved and regular inflow through the popliteal artery, peroneal occlusion at the midcalf, and preserved two-vessel outflow to the foot by way of diseased but patent anterior tibial and posterior tibial arteries.

Diagnosis and Treatment

This patient has nonhealing wounds of arterial insufficiency affecting multiple toes and associated with underlying osteomyelitis. Treatment options should consider the need for revascularization to ensure healing while identifying the indication for amputation and optimal level for such.

In situations of chronic critical limb ischemia, amputation is indicated for unreconstructable arterial disease, failed attempts at revascularization, patient comorbidities that prohibit candidacy for revascularization, and extensive tissue loss complicated by gangrene and/or infection (including pedal sepsis).

Given the dry gangrenous changes described and associated osteomyelitis, this patient requires amputation. While individual toe amputations may suffice, in clinical situations that require the removal of multiple toes, TMA offers a functional benefit; additionally, TMA is indicated for source control of extensive soft tissue infection of the forefoot.

While there is no definitive independent predictor of transmetatarsal healing when considering preoperative patient factors, skin temperature measurements, radioisotope scans, and skin perfusion pressure, a toe pressure of less than 38 mm Hg has been associated with failure of “minor amputations” in diabetic patients. This patient’s biphasic waveform suggests the ability for TMA healing.

Surgical Approach

While it is likely that this patient will heal a TMA based on the above discussion, there are additional more proximal amputations that warrant discussion including the Lisfranc and Chopart amputations. Lisfranc’s amputation results in a disarticulation of the first, third, fourth, and fifth tarsometatarsal joints, while the second metatarsal is divided up to two centimeters distal to the medial cuneiform. Chopart’s amputation is performed through the talocalcaneonavicular joint and the calcaneocuboid joint. Both of these amputations result in a dramatic alteration in the biomechanics of the normal foot; additionally, comfortable and functional prosthetic fitting is challenging. Most authors suggest below-knee amputation (BKA) over the Lisfranc or Chopart amputations in clinical settings of tissue malperfusion that will not permit TMA healing in an effort to avoid altered ambulatory biomechanics and favor the more functional prosthetic limbs available to BKA patients.

The leg should be circumferentially prepped and draped; efforts at preserving a clean (albeit contaminated field in the setting of active tissue loss) should be maintained with occlusive dressings applied to any open wounds prior to skin preparation. A skin incision is made allowing for a plantar flap by constructing the transverse dorsal incision at the level of the midmetatarsal shafts from a point medial to the first metatarsal head to the opposing lateral side of the fifth metatarsal head. The incision is extended at right angles and along the metatarsophalangeal crease of the plantar aspect of the foot. The extensor tendons are divided proximal to the metatarsal heads, and each metatarsal shaft is divided using a power saw. It is important at this step to divide the bones approximately 1 cm proximal to the edge of the dorsal skin incision. The plantar tissues are then separated from the metatarsal shafts and dissected to excise exposed flexor tendons. The plantar flap is then extended over the dorsal aspect of the foot for closure. Ensure adequate hemostasis and consider pulse irrigation of the surgical bed prior to closure, especially in settings of active tissue loss. The flap should be closed in two layers with interrupted absorbable sutures reapproximating the fascia and a nonabsorbable suture by vertical mattress technique versus the use of staples reapproximating the skin to allow for minimal tension on the incision.

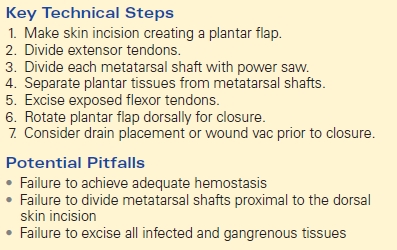

Potential pitfalls might result in a necessity for early reoperation, a delay in wound healing, or impaired prosthetic function and/or comfort. It is important to achieve adequate hemostasis prior to flap closure to avoid hematoma formation. Avoid unnecessary or overly restrictive compression bandages (i.e., ACE wrap) that may compromise skin flap viability. Ensure that the metatarsal shafts are divided 1cm proximal to the dorsal skin incision (as emphasized above) as this will prevent sharp bony protrusion into the incision and subsequent skin erosion in addition to minimizing the risk for potential future pressure points. Lastly, failure to excise all gangrenous or infected tissue will predictably result in worsening infection leading to nonhealing requiring subsequent reamputation, or possibly systemic spread and sepsis. In clinical scenarios of infected tissue loss, consider sending proximal bone samples for culture as this will guide postoperative antibiotic therapy selection and duration (Table 1).

TABLE 1. Transmetatarsal Amputation