Figure 7.1

The patient receives general anesthesia and is intubated with a modified double-lumen endotracheal tube. To facilitate custom resizing of the airway, the tracheal lumen of a double-lumen tube is shaved off with a scalpel before intubation. This procedure allows a very thin tube to be placed within the airway with minimal distention or distortion and avoids using the longer cuff, which might herniate or be pierced by a suture if a single-lumen tube is used and simply advanced to a left mainstem bronchus position. A standard right posterolateral thoracotomy is used. For postoperative analgesia for this incision, an epidural catheter is placed preoperatively. The azygous vein is ligated, and the pleura overlying the posterior membranous trachea is dissected from the thoracic inlet to the mainstem bronchi. Care is taken to avoid damage to the vagus nerves or either recurrent laryngeal nerve during the course of the dissection. Dissection of the lateral walls of the airway also is avoided to preserve the segmental blood supply of the trachea. The right mainstem bronchus and bronchus intermedius are dissected free to the level of the superior segment bronchial takeoff. The left mainstem bronchus is retracted from the mediastinum as dissection continues down to the level of the bifurcation of upper and lower lobes, if possible. Although malacia may predominate in a more localized portion of the airway, most cases requiring TBP are diffuse and severe, requiring this extensive exposure for repair. Following exposure, the transverse diameter is measured at the proximal trachea, distal trachea, mainstem bronchi, and bronchus intermedius

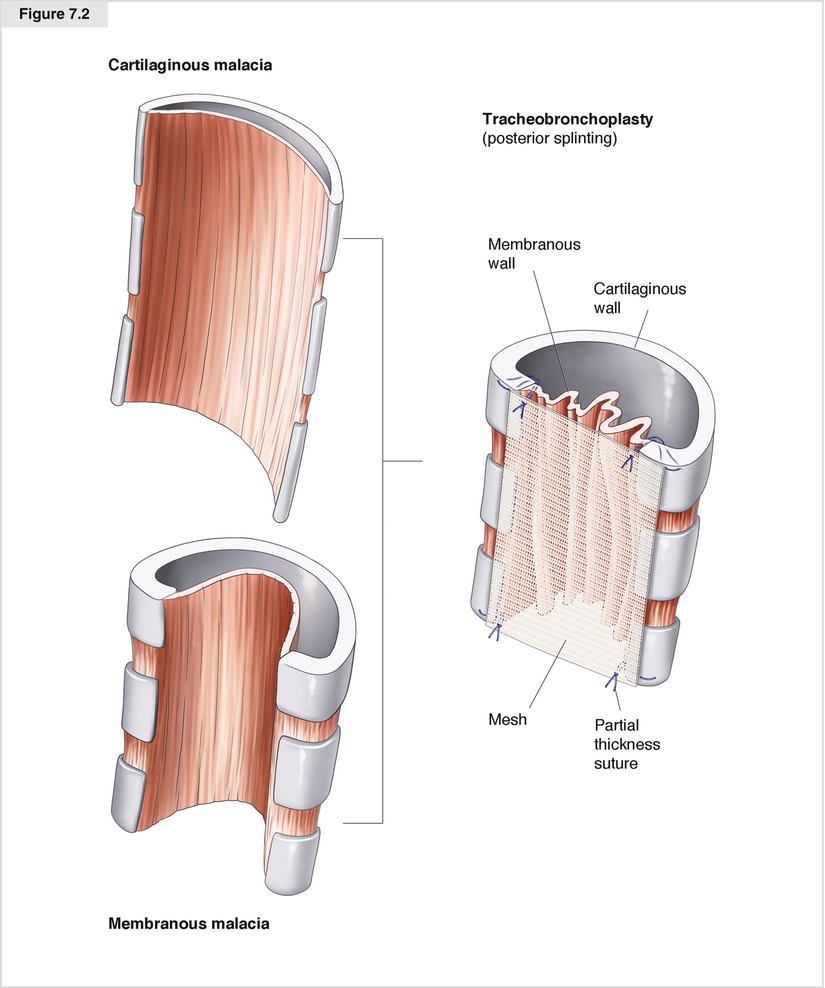

Figure 7.2

The principle of TBP is to stabilize the posterior membrane of the malacic airway with a polypropylene mesh, which is affixed in rows of polypropylene sutures placed in partial-thickness fashion through the airway wall. Airways with malacia ranging from primarily cartilaginous to primarily membranous are all candidates for the procedure. Depending on the degree of cartilaginous bowing of the airways, varying degrees of mesh “cinching” (creation of medial tension on the cartilaginous ends) are used. In general, a 30–40 % reduction in the transverse diameter is achieved, but in small airways with dynamic membranous intrusion alone, much less airway narrowing may be desirable

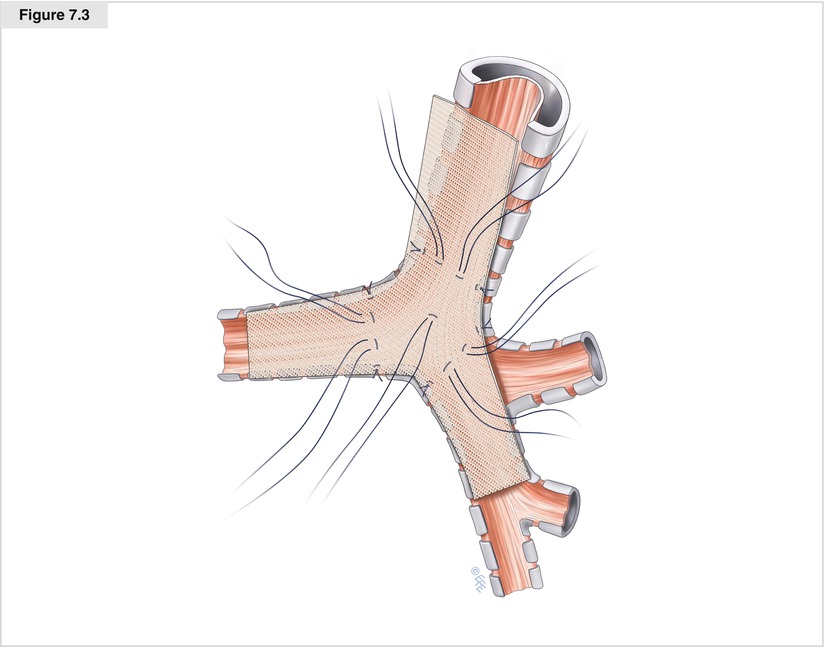

Figure 7.3

Although some groups favor the use of three separate pieces of mesh to splint the trachea and bilateral bronchi (Wright et al. 2005), we use a single Y-shaped piece of mesh (Majid et al. 2008). Once the degree of downsizing of the transverse diameter is determined, the mesh is cut with a 0.5-cm border around it to avoid having to suture the very edge of the mesh, which may fray. The initial suture rows are placed in the carinal region in a triangle—one row across the distal trachea, one across the proximal right mainstem bronchus, and one across the proximal left mainstem bronchus—and a single suture is placed in the membranous wall in the center of this triangle. Rows of four sutures are used, with the two lateral sutures placed in the cartilaginous–membranous junctions and the two membranous wall sutures placed one third and two thirds the way across the membranous wall. The sutures are placed in partial-thickness mattress fashion, with each row’s sutures placed in order from one cartilaginous–membranous junction to the two membranous wall sutures to the contralateral cartilaginous–membranous junction so that minor adjustments in spacing may be made from row to row. Once the carinal triangle is completed, the mesh is parachuted into place and the sutures of each row are tied, first the cartilaginous–membranous sutures of each side then the two membranous wall sutures. Suture placement near the endotracheal tube balloon is facilitated by periods of apnea and partial withdrawal of the tube

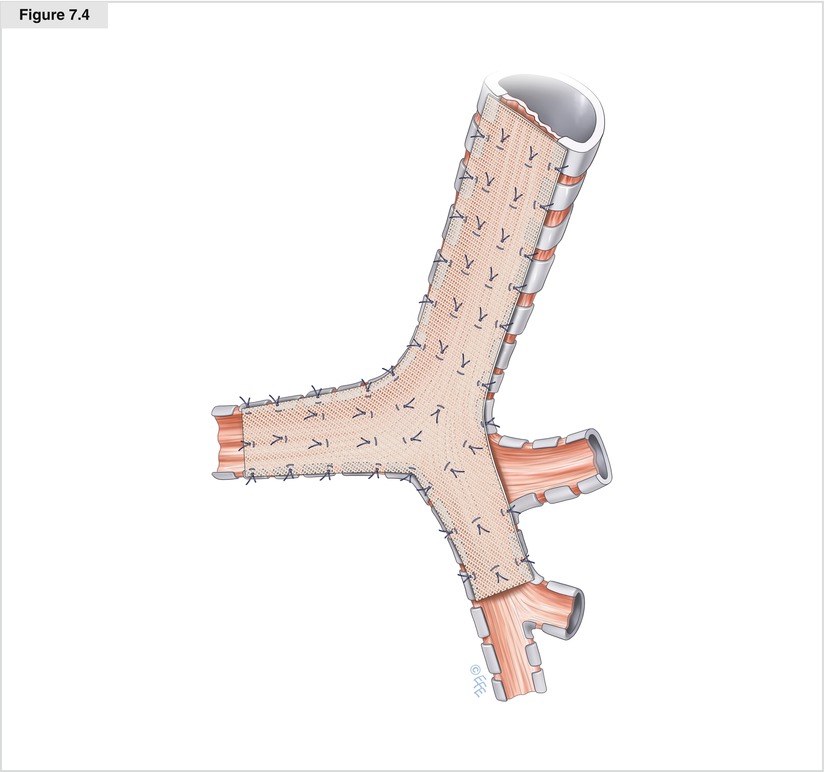

Figure 7.4

With the mesh affixed to the carinal triangle, the tracheal splinting is completed, with the rows progressing distally to proximally on the airway. Each row is spaced 5–7 mm from the last as the entire thoracic trachea is stabilized, all the way up to the inlet. One centimeter of extra mesh is tucked into the inlet above the level of the highest row of sutures. The right mainstem bronchus and bronchus intermedius are completed next. As the airway narrows distally, rows of three sutures may be used. Excessive narrowing of the smaller airways is avoided. In addition, undue axial compression at the level of the right upper lobe takeoff must be avoided so that the lobar orifice is not obstructed. The left mainstem bronchus requires careful retraction of the esophagus posteriorly and rightward retraction of the airway to allow the splinting to continue to the distal aspect of the bronchus. At the completion of the procedure, but prior to chest closure, bronchoscopy is performed to assess the appearance of the repair and assure that no obstruction was created. It is normal to see some bulging or quilting of the membranous wall as the redundancy is taken up by the mesh. If inadvertently intraluminal sutures are detected, they may be removed at this time to prevent contamination of the mesh from bacteria tracking extraluminally along the suture. The chest is irrigated and the airway inspected for any sign of air leak. A chest drain is placed, and the thoracotomy is closed in the standard fashion (Gangadharan et al. 2011)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree