Fig. 1.

Patterns of lung nodule calcification

Soft-Tissue Attenuation Nodules

Most soft-tissue attenuation nodules on CT are indeterminate. In the absence of a known malignancy, the vast majority of tiny (<5 mm) solid nodules are benign. The rate of malignancy increases with size. Guidelines exist for the management of incidental small solid nodules. However, they are not applicable to patients with known malignancy. In most cases, if not recently performed, a dedicated non-contrast chest CT is warranted to fully characterize incidental nodules on hybrid imaging.

Fat-Attenuation Nodules

Nodules with macroscopic fat apparent on chest CT often represent pulmonary hamartomas (mesenchymomas). These nodules can be purely fat, primarily soft tissue, or contain coarse “popcorn” calcification. Hamartomas typically show no increased metabolic activity on nuclear imaging, although they can grow slowly over several years.

Diffuse Micronodules

The differential diagnosis of diffuse micronodules (<10 mm diameter) depends on their distribution in the lungs. The spatial resolution of CT technique used in hybrid imaging is typically not sufficient enough to fully characterize the morphology and distribution of diffuse micronodules. However, occasionally, small branching (Y- or V-shaped) opacities (tree-in-bud) may be apparent on hybrid imaging studies. Tree-in-bud opacities are a CT finding of bronchiolitis and nearly always reflect infection. Occasionally, tree-in-bud opacities reflect bronchiolitis from aspiration and may be encountered in patients undergoing hybrid imaging for esophageal carcinoma or head and neck malignancies. Clues to the diagnosis include a gravitationally dependent distribution as well as ancillary findings such as a large hiatus hernia or fluid in the esophagus.

Emphysema

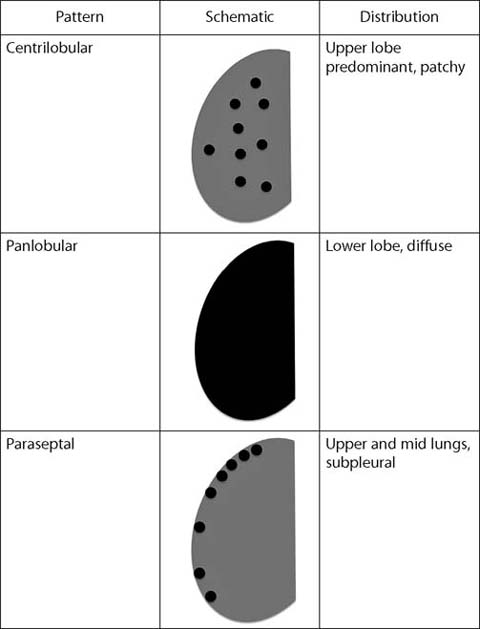

Emphysema (Fig. 2) is the process of airspace expansion and alveolar destruction with minimal fibrosis. Most emphysema is the result of cigarette smoking. Emphysema is frequently encountered in patients undergoing hybrid imaging for lung cancer staging. Emphysema is classified based on its histopathologic morphology, but strong correlation with CT appearances allows for use of the same classification scheme.

Fig. 2.

Patterns of emphysema

Centrilobular Emphysema

Centrilobular emphysema occurs in the central portion of the pulmonary lobule, around the lobular bronchiole and lobular pulmonary artery. It is almost always the result of cigarette smoking and has a predilection for the upper lobes and superior segments of the lower lobes. On CT, centrilobular emphysema appears as round foci of low attenuation. A punctate opacity may be visible within the emphysematous lesion, representing the lobular artery.

Panlobular Emphysema

Panlobular emphysema reflects emphysematous destruction of an entire pulmonary lobule and often affects most if not all of an entire segment or lobe. Panlobular emphysema is most commonly associated with alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency and predominates in the lower lobes. CT shows large foci of low attenuation, hyperinflation, and attenuated pulmonary vasculature.

Paraseptal Emphysema

Paraseptal emphysema occurs in the periphery of the pulmonary lobule and usually develops along pleural spaces. It may occur in isolation but more often in conjunction with centrilobular emphysema. Large (<10 mm) paraseptal emphysematous lesions are termed bullae and can become quite large.

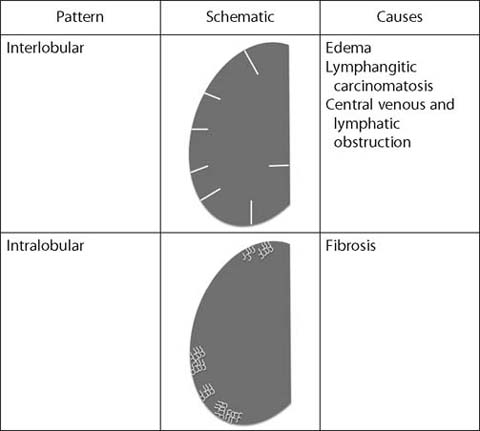

Linear Opacities

Fine linear (or reticular) opacities (Fig. 3) may be identified on CT performed as part of hybrid imaging studies. These opacities can be described as interlobular (or septal) or irregular (intralobular).

Fig. 3.

Fine linear (reticular) opacities

Interlobular Septal Thickening

Interlobular septal thickening occurs when fluid, cells, or fibrosis fill and expand the normal septum that surrounds the pulmonary lobule. It is usually apparent on CT performed in conjunction with PET. Septal thickening most commonly reflects lung edema and may be seen in patients with congestive heart failure or other causes of lung edema. The primary differential diagnosis is lymphangitic carcinomatosis, which occurs when tumor cells invade and obstruct the pulmonary lymphatics. Whereas septal thickening from lung edema is typically bilateral, symmetric, and gravitationally dependent, septal thickening from lymphangitic carcinomatosis is more often randomly distributed. In the setting of a centrally obstructing mass (usually lung carcinoma), septal thickening may be observed in the affected lobe(s) as a result of central lymphatic and venous obstruction.

Intralobular Lines

Intralobular lines occur within a pulmonary lobule and are nearly always the result of pulmonary fibrosis. These irregular lines may be more difficult to detect on attenuation correction CT but can be seen when fibrosis is more extensive. Most pulmonary fibrosis occurs in the lung bases. Other findings associated with pulmonary fibrosis include traction bronchiectasis and honeycomb cysts. Pulmonary fibrosis may be encountered in patients with a history of cigarette smoking and in those with collagen vascular diseases. If clinically appropriate, full characterization can be performed with dedicated noncontrast thin-section chest CT.

Cysts

Lung cysts (Table 1) are low attenuation foci in the lungs surrounded by a thin, smooth wall. Single or a small number of cysts can be found in healthy patients and require no further evaluation. However, some lung diseases can primarily manifest by the development of extensive lung cysts.

Table 1.

Causes of lung cysts

Disease | Distribution | Other features and associationss |

|---|---|---|

Pulmonary Langerhans cell histiocytosis | Upper lungs | Bizarre shapes |

Nodules | ||

Cigarette smoking (>97%) | ||

Lymphoid interstitial pneumonia | Basal predominant | Perivascular |

Nodules (±calcification) | ||

Septal lines | ||

Ground-glass opacity | ||

Collagen-vascular disease (especially Sjögren syndrome) | ||

Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome | Basal predominant | Bilenticular |

Renal neoplasms | ||

Skin lesions on face and upper trunk |

Pulmonary Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis

Pulmonary Langerhans cell histiocytosis (PLCH) occurs almost exclusively in adult smokers and is characterized by the formation of nodules and cysts that predominate in the upper lungs. With progressive disease, the number and size of cysts increase as the profusion of nodules diminishes. Larger cysts may have bizarre shapes. PLCH may be encountered in hybrid imaging in patients being staged for lung cancer and should not be mistaken for metastases.

Lymphoid Interstitial Pneumonia

Lymphoid interstitial pneumonia (LIP) is part of the spectrum of pulmonary lymphoproliferative disorders and is characterized by infiltration and expansion of the pulmonary interstitium by a polyclonal mix of lymphoid cells. In adults, it is most commonly associated with Sjögren syndrome and thus may be encountered on hybrid imaging performed for staging of lymphoma. On CT, LIP is characterized by the presence of basal-predominant cysts, ranging up to approximately 30 mm in diameter. Frequently, a vessel can be observed coursing along the wall of the cyst. Other CT features of LIP include nodules (soft tissue or calcified, the latter often reflecting amyloid deposition), septal lines, and ground-glass opacity.

Birt-Hogg-Dubé Syndrome

This autosomal dominant disease is characterized by the development of soft-tissue lesions on the face and upper trunk (primarily fibrofolliculomas), lung cysts, and renal neoplasms. Many patients report a personal or family history of spontaneous pneumothorax. The lung cysts in Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome have a characteristic bilenticular shape and a predilection for the lower lobes, along the pulmonary fissures, pulmonary veins, and septopleural junction. These cysts may be encountered in patients undergoing hybrid imaging for renal cell carcinoma, and the diagnosis should be suggested given the implications for nephronsparing therapy and the screening of family members.

Lung Consolidation

Lung consolidation (Table 2) is defined as increased attenuation of the lung parenchyma such that the underlying architecture is obscured. CT typically cannot establish the cause of lung consolidation but common causes include infection, hemorrhage, neoplasm, edema, and noninfectious inflammation such as organizing or eosinophilic pneumonia. Typically, obtaining additional clinical information is sufficient to establish a cause for the consolidation.

Table 2.

Causes of lung consolidation

Cause | Other clues |

|---|---|

Hemorrhage | Acute hypoxia and dyspnea |

Hemoptysis (~50%) | |

Infection | Fever |

Leukocytosis | |

Purulent sputum | |

Edema | Other signs of heart or kidney failure |

Pleural effusion | |

Cardiomegaly | |

Neoplasm (lung Slowly progressive adenocarcinoma or lymphoma) | Pseudocavitation (adenocarcinoma) |

Bronchial stretching (adenocarcinoma) | |

Organizing pneumonia (OP) and eosinophilic pneumonia | Peripheral and peribronchial distribution |

Reversed halo sign (OP) | |

Drug reaction (antibiotics and chemotherapeutic agents) | |

Large opacities of pneumoconiosis | Background of small pneumoconiotic nodules |

Upper lung predominant | |

Coalescence of small nodules | |

Lateral margins typically smooth | |

Volume loss in affected lobe(s) |

Lung Carcinoma Presenting as Consolidation

Non-resolving, slowly progressive lung consolidation is an uncommon manifestation of lung carcinoma. Many of these neoplasms are mucinous adenocarcinomas and can grow slowly over several years. It is often the case that patients are initially diagnosed as having recurrent infection. Documenting slow progression across serial examinations usually suggests the diagnosis. Percutaneous or transbronchial biopsy usually confirms the diagnosis. Clues to the diagnosis on CT include lucencies within areas of consolidation (pseudocavitation), small solid and subsolid nodules adjacent to larger areas of consolidation, and distortion (stretching) of the involved bronchi.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree