Chapter 12 Thromboembolic Disease

Historical Background and Epidemiology of Acute Venous Thromboembolic Disease

The incidence of deep venous thrombosis (DVT) ranges from 5 to 9 per 10,000 person-years in the general population, and the incidence of venous thromboembolism (DVT and pulmonary embolism [PE] combined) (VTE) is about 14 per 10,000 person-years.1,2 This equates to more than 275,000 new cases of VTE per year in the United States.3 The number of identifiable risk factors that predispose to the development of VTE has steadily grown. This information has allowed physicians to provide more effective thromboembolism prophylaxis that is evidence-based and stratified according to the number of risk factors present. In patients with established DVT and PE, there has been a relatively recent emphasis evaluating the rate of recurrence and the clinical factors that predispose to recurrent VTE. In turn, the type and duration of long-term anticoagulation also continue to be stratified, based on the number of risk factors for recurrence.

Etiology and Natural History of Acute Venous Thromboembolism

Etiology

Venous thrombosis may develop as a result of endothelial damage, hypercoagulability, and venous stasis (Virchow triad). Of these risk factors, relative hypercoagulability appears most important in most cases of spontaneous DVT, whereas stasis and endothelial damage play a greater role in secondary DVT following immobilization, surgery, or trauma. Identifiable risk factors for VTE may be classified as inherited, acquired, and those with a mixed etiology (Table 12-1).

![]() TABLE 12–1 Common Inherited and Acquired Risk Factors for Venous Thrombosis

TABLE 12–1 Common Inherited and Acquired Risk Factors for Venous Thrombosis

| Acquired | Inherited |

| Mixed Etiology | |

APC, Activated protein C; HRT, hormone replacement therapy; OCP, oral contraceptives; VTE, venous thromboembolism.

When multiple inherited and acquired risk factors are present in the same patient, a synergistic effect may occur. Clinically manifest thrombosis most often occurs with the convergence of multiple genetic and acquired risk factors.4 Hospitalized patients have an average of 1.5 risk factors per patient, with 26% having three or more risk factors.5 Multiple risk factors often act synergistically to increase risk dramatically above the sum of individual risk factors. For example, patients who are heterozygous for factor V Leiden are at only moderately increased risk for VTE (4- to 8-fold). However, when combined with the additional risk of oral contraceptive use, the risk for VTE increases to approximately 35-fold, the same order of magnitude as for someone who is homozygous for factor V Leiden. The concomitant presence of obesity, advancing age, and factor V Leiden increases the thrombosis risk associated with hormone replacement therapy alone. In symptomatic outpatients, the odds ratio for an objectively documented DVT increases from 1.26 for one risk factor to 3.88 for three or more risk factors.6

Natural History

Overt venous injury appears to be neither a necessary nor sufficient condition for thrombosis, although the role of biologic injury to the endothelium is increasingly apparent. Under conditions favoring thrombosis, the normally antithrombogenic endothelium may become prothrombotic, producing tissue factor, von Willebrand factor, and fibronectin. Stasis alone is probably also an inadequate stimulus in the absence of low levels of activated coagulation factors.7

Diagnosis and Imaging

Imaging

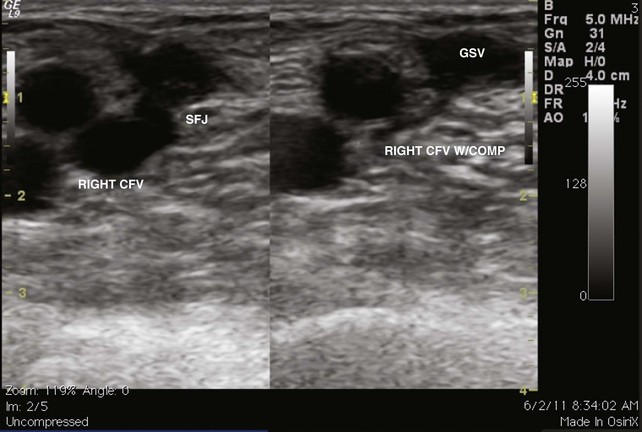

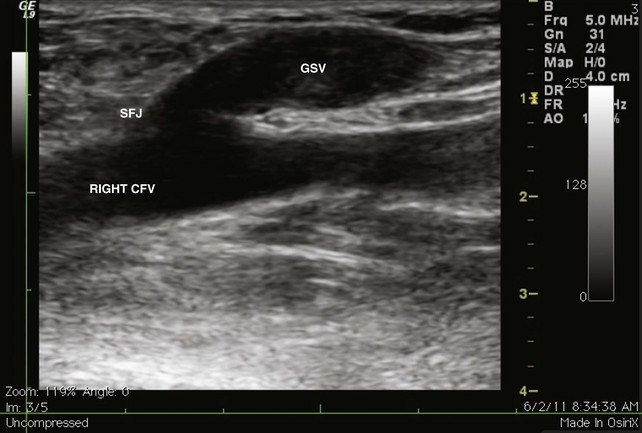

The venous duplex scan is the most commonly performed test for the detection of infrainguinal DVT, both above and below the knee, with sensitivity and specificity of greater than 95% in symptomatic patients. In a venous duplex examination performed with the patient supine, spontaneous flow, variation of flow with respiration, and response of flow to the Valsalva maneuver, all are assessed. Continued improvements in ultrasound technology also have improved the ability to visualize color flow within the tibial veins. However, the primary method of detecting DVT with ultrasound is demonstration of the lack of compressibility of the vein with probe pressure on B-mode imaging. Normally, in transverse section, the vein walls should coapt with pressure (Figs. 12-1 and 12-2). Lack of coaptation indicates thrombus.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree