Chapter 79

Thromboangiitis Obliterans (Buerger’s Disease)

Ahmet Rüçhan Akar, Serkan Durdu

Based on a chapter in the seventh edition by A. Ruchan Akar and Serkan Durdu

Thromboangiitis obliterans (TAO), also known as Buerger’s disease or von Winiwarter–Buerger syndrome, is a chronic, inflammatory, thrombotic, nonatherosclerotic, segmental, obliterative, tobacco-associated vasculopathy primarily involving infrapopliteal and infrabrachial medium-sized and small arteries of predominantly young male smokers. TAO is a clinical diagnosis and often is manifested with distal extremity ischemia in a heavy male smoker before the age of 45 years. On pathologic examination, Buerger’s disease is characterized by a highly cellular arterial thrombus, extensive intimal inflammation, and preserved internal elastic lamina. The disease frequently involves adjacent superficial veins and nerves. Absence of markers of inflammation and autoantibodies is unique for TAO in comparison to other types of vasculitis.

Patients experience periods of acute exacerbation leading to critical limb ischemia associated with smoking, which may result in tissue loss and major amputations. Remissions follow abstinence from tobacco or can occur in the fifth to sixth decades of life. Cerebral, coronary, visceral, ophthalmic, and multisystem arterial involvements have also been described. A number of studies agree that tobacco use has a strong link to the pathogenesis and progression of TAO (see Chapter 27). Indeed, the only fully effective therapy for Buerger’s disease is complete and permanent discontinuation of smoking. Local wound care is also essential in patients with ischemic ulcers. Prostacyclin analogues, distal arterial revascularization, and gene and stem cell–based therapies may help patients with severe limb ischemia.

Brief Historical Review

Reports resembling TAO have appeared in medical writings since the mid-1800s, but the cases were labeled arteriosclerosis obliterans (ASO) or frostbite because of the lack of pathologic confirmation.1 Felix von Winiwarter, a pupil of Theodor Billroth at the University Clinic in Vienna, is credited with the first description of the clinical entity in 1879. He documented the results of an autopsy on a 57-year-old man with a 12-year history of foot pain that eventually progressed to gangrene and limb loss. von Winiwater was the first to suggest the “new growth of tissue from the intima” (termed endarteritis and endophlebitis) in the amputated specimen that was distinct from atherosclerosis.2 In 1908, Leo Buerger (1879-1943), working at Mount Sinai Hospital in New York, provided a detailed and accurate description of the pathologic findings of a new and unusual form of progressive vaso-occlusive disease in 11 limbs amputated from young Polish and Russian immigrant Jews.3 On the basis of his findings, Buerger named the disease thromboangiitis obliterans to distinguish it from arteriosclerosis obliterans. Buerger’s 32-chapter, 628-page monograph entitled The Circulatory Disturbances of the Extremities was published in 1924.4 Four years later, Allen and Brown reported on 200 cases of TAO evaluated at the Mayo Clinic from 1922 to 1926.5 However, between the 1930s and 1960s, numerous investigators expressed skepticism concerning the identity of TAO.6–8 In the early 1960s, several authorities considered TAO a distinct clinical and pathologic entity that should be separated from ASO.9–13 Today, TAO is accepted as a definite vasculopathy with a typical clinical picture, natural history, and histopathology.14–19

Epidemiology

Studies of the epidemiology of TAO have been hampered by the rarity of the disease in central Europe, North America, Latin America, and Africa and by the absence of universally accepted diagnostic criteria. Therefore, many studies have been based on calculations from highly selected series of patients treated at specialized institutions, not from the general population.20

Population Affected

TAO is found worldwide; it affects both sexes and all races,16,17,21,22 but with uneven gender and geographic distribution and probable ethnic predisposition.23 Buerger’s view of the disease as being largely restricted to the Jewish race is no longer valid.4,24 The only risk factor consistently reported is smoking. The strong correlation between tobacco use and the pathogenesis, initiation, and progression of the disease is well established.14,17,21,25–28 There is also a higher incidence of TAO among individuals with cigar and pipe smoking and habitual homemade cigarette smoking (such as bidi smoking in India, Bangladesh, and Ceylon29; kawung smoking in Indonesia30,31; and chewed miang [steamed tea leaves] or khiyo [the homemade raw tobacco in hand-rolled banana leaves] smoking in Thailand) as well as in users of smokeless tobacco and marijuana.17,32–34 In 1969, Kjeldsen and Mozes demonstrated that patients with TAO have greater tobacco consumption and higher carboxyhemoglobin levels than patients with ASO and control subjects without vascular disease.35 There is a higher incidence of TAO among individuals of lower socioeconomic class who smoke homemade cigarettes. Furthermore, Tseng and colleagues demonstrated a close relation between long-term arsenic exposure from artesian well water and endemic blackfoot disease in Taiwan.36,37 In fact, arsenic adulteration of tobacco as a causative agent of TAO has been suggested in populations smoking bidis or kawung.38–41

Prevalence

There is an estimated worldwide prevalence of 5 to 12 per 100,000 population per year, ranging from 0.25 to 693 per 100,000 population per year. The prevalence is higher in the Middle East, South and Southeast Asia, Far East, Mediterranean, and eastern European countries than in central Europe and North America.16,42–45 At the Mayo Clinic, the prevalence rate of patients with the diagnosis of Buerger’s disease has steadily declined from 104 per 100,000 patient registrations in 1947 to 12.6 per 100,000 patient registrations in 1986.15,46 The overall prevalence of TAO ranges from approximately 5 cases per 100,000 persons among the Japanese population to more than 10 per 100,000 persons among populations in the Middle East, Asia, Mediterranean, and eastern European countries. In Latin America and Africa, Buerger’s disease is rarely reported.47 Buerger’s disease accounts for a variable proportion of patients with peripheral vascular disease throughout the world: 0.75% in North America, 0.5% to 5.6% in western Europe,42,48–51 3% to 39% in eastern Europe and the Mediterranean,45,50,52 80% in Israel among Jews of Ashkenazi ancestry,35 16% in Japan,53–55 66% in Korea, and 45% to 63% in India.16 Pooled characteristics of patients with TAO are listed in Table 79-1.

Table 79-1

Pooled Characteristics of Patients with Thromboangiitis Obliterans from Different Regions Globally

| Prevalence | Uncommon |

| Incidence | Declining |

| Involved arterial size | Small and medium |

| Age at diagnosis (years) | 29-42 |

| Age at hospital admission (years) | 42.5 ± 8.4 |

| Male, % | 77-98 |

| Female, % | 2-23 |

| History of smoking, % | 93-94 |

| Intermittent claudication, % | 17-62 |

| Rest pain, % | 46-89 |

| Ischemic ulcers and gangrene, % | 38-85 |

| Upper extremity | 2-21 |

| Lower extremity | 35-93 |

| Both | 16-20 |

| Migratory superficial phlebitis, % | 40-62 |

| Deep venous thrombosis | Unusual |

| Raynaud’s phenomenon, % | 10-45 |

| Sensory findings, % | 69 |

| Abnormal Allen’s test result, % | 63 |

| Joint manifestations, % | 12.5 |

Modified from Olin JW: Thromboangiitis obliterans (Buerger’s disease). N Engl J Med 343:864-869, 2000; Puechal X, et al: Thromboangiitis obliterans or Buerger’s disease: challenges for the rheumatologist. Rheumatology (Oxford) 46:192-199, 2007; and Mills JL Sr: Buerger’s disease in the 21st century: diagnosis, clinical features, and therapy. Semin Vasc Surg 16:179-189, 2003.

The overall incidence of TAO appears to be decreasing in North America, western Europe, South Asia, and Japan.25,55,56 A reduction in smoking among the populations studied as well as adoption of stricter diagnostic criteria may explain the reasons for this decline during the past 4 decades. In 1976, data from the TAO research committee of the Ministry of Health and Welfare of Japan estimated the incidence of TAO to be about 5 per 100,000 population in Japan.57 In 1986, the Epidemiology of Intractable Disease Research Committee of the Ministry of Health and Welfare of Japan estimated that 8858 patients with the disease were treated at various medical institutions (5 per 100,000 population)58 and that the prevalence among manual laborers was not significantly greater than that among other individuals. In 2006, Kobayashi and colleagues reported that the ratio of new patients with TAO to new patients with ASO was 1 : 3 during the 1990s.59 Since 2000, the ratio has declined to 1 : 10 at the vascular outpatient clinic of Nagoya University.59 According to a national survey by Japan Tobacco, 82.3% of Japanese adult men smoked in 1965, 70.2% in 1980, and 58.8% in 1995.59 Although the number of new patients with TAO in Japan has been decreasing, the number of patients under the care of physicians remains almost unchanged owing to frequent recurrences.55

Natural History

TAO is a relatively common cause of peripheral vascular disease in young people and may cause disability in patients of all ages. The adverse effects of environmental tobacco smoke are well established in patients with TAO. Patients with TAO have a significantly diminished quality of life compared with age- and sex-matched controls in several studies.60,61 Of note, most patients with TAO improve with cessation of smoking. Cooper and associates demonstrated that a TAO population and a matched coronary artery disease population had similar degrees of tobacco dependence and Fagerström scores.62

In one study, the life expectancy of patients with TAO was comparable to that of the normal population.11 In contrast, Cooper and colleagues reported that survival among the TAO cohort was significantly lower than that in the matched U.S. population (P < .001 by log-rank test); in the TAO group, the average age at death was 52.2 ± 8.9 years.60 Cumulative survival rates in the series reported by Ohta and colleagues were 97.0% at 5 years, 94.4% at 10 years, 92.4% at 20 years, and 83.8% at 25 years (mean follow-up, 10.6 years).61 These investigators also demonstrated that necrotic lesions rarely occurred or recurred in patients older than 60 years.61 Ateş and coworkers reported similar survival rates: 95.0% at 2 years, 92.4% at 5 years, and 88.4% at 10 years (mean follow-up, 11.6 years).63

Buerger’s Disease in Women

TAO has a striking predominance in men, especially in series reported before 1980. The reported incidence of TAO in women was less than 2% in most published series during that era. Indeed, only 2 of Buerger’s 500 reported cases were women.4 However, TAO is no longer exclusively seen in male patients (see Table 79-1).23,64,65 During the last 3 decades, this apparent gender discrimination for TAO is disappearing, probably as a result of the rising use of tobacco products by young women.25,66 In recent series, 11% to 23% of patients were women.15,25,43,67 Currently, the male-to-female ratio is estimated between 10 : 1 and 5 : 1.17,23,25,43,68 A limited number of pregnancies among patients with active TAO have also been reported.69–72

Pathogenesis

Etiology

The etiology of Buerger’s disease remains unknown.15,16,44,73,74 There has been considerable speculation as to the possible etiologic factors and mechanisms.16,20,44 Autoimmune mechanisms, genetic predisposition, hypercoagulable states, and an oral infection–inflammatory pathway have been suggested as potential etiologic factors (Box 79-1). Smoking is the major contributing risk factor for TAO. Buerger’s disease in nonsmokers has occasionally been reported; however, these sporadic cases are not well documented.16,22,25,28,75,76 Lower socioeconomic status, poor oral hygiene, nutritional deficits, a history of viral or fungal infection, cold injury, abuse of sympathomimetic drugs, and arsenic intoxication are reported as other possible risk factors.30,35,40,49,77–80 An emerging body of evidence demonstrates that ischemia induced by cocaine and cannabis ingestion can closely mimic TAO81–86 or may accelerate TAO onset and presentation.86

Smoking and Immunologically Mediated Injury

The close association of the disease activity with the use of tobacco in any form is beyond debate. In 1945, Silbert reported that TAO develops in individuals who are constitutionally sensitive to tobacco.87 Matsushita and associates, using urinary levels of cotinine, showed a very close relationship between active smoking and the aggravation of Buerger’s disease.88

Several observations implicate an immunologic phenomenon in the etiology of Buerger’s disease. In 1933, Harkavy suggested the possibility of hypersensitivity to tobacco antigens.89 Increased cellular sensitivity to collagen type I,48,90,91 type III,48 and type IV92 have been reported in patients with TAO compared with patients with atherosclerosis and healthy male controls. Circulating immune complexes have been found in the peripheral arteries of some patients with TAO.93–95 It has been suggested that an unidentified antigen possibly related to a constituent of tobacco smoke triggers immunologic damage to the arterial intima.96 Previous data suggest that T cell–mediated cellular immunity and B cell–mediated humoral immunity associated with the activation of macrophages or dendritic cells in the intima play a key role in Buerger’s disease.79

Previous studies showed activation of endothelial cells associated with tumor necrosis factor-α secretion by tissue-infiltrating mononuclear inflammatory cells and expression of intracellular adhesion molecule-1, vascular cellular adhesion molecule-1, and E-selectin on endothelial cells in TAO patients.97 Increased levels of tumor necrosis factor-α and interleukins 1β, 4, 17, and 23 were reported in patients with TAO compared with the controls (P < .005), suggesting an autoimmune pathologic process.98 Furthermore, an experimental study confirmed the key role of high-mobility-group box protein 1 (HMGB1), which may contribute to the pathogenesis of TAO by binding to its receptor RAGE in sodium laurate–induced TAO rats.99 HMGB1 not only induces the production of inflammatory mediators by mononuclear cells but also activates endothelial cells, leading to the upregulation of the adhesion molecules. Recombinant A box (rA box), the antagonist of HMGB1, improved the pathologic condition by inhibiting the release and injury of inflammatory mediators and improving the hypercoagulable state of blood.99 Thus, immunologically mediated inflammation of vessels is thought to be a contributing cause of arterial or venous thrombosis and vascular occlusion in TAO.

A study from Colombia reported the presence of elevated anticardiolipin antibody titers in 3 of 30 TAO patients.47 The prevalence of anticardiolipin antibodies measured by double-antibody sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay was significantly higher in patients with TAO (36%) compared with those with premature atherosclerosis (8%; P = .01) and in healthy individuals (2%; P = .001).100 Patients with TAO and high antibody titers tended to be younger and to have significantly higher rates of major amputations than did those without the antibody (100% vs 17%; P = .003). However, because of the methodologic problems with this study pointed out by Olin,101 further research is needed to confirm this observation. Since then, several case reports have been published indicating a poor prognosis when anticardiolipin autoantibodies are detected in TAO patients.102,103 Of note, the clinical picture of antiphospholipid syndrome in young smokers may mimic that of Buerger’s disease.104

In 27 patients with TAO, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies were detected by indirect immunofluorescence in 55% of patients and by fixed neutrophil enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay in 59%.105 Eichhorn and colleagues showed that 7 patients with active TAO had higher anti–endothelial cell antibody titers than did 30 normal healthy subjects (P < .001) and 21 patients in remission (P < .01).106

Genetic Predisposition

The importance of a genetic predisposition to tobacco sensitivity is not well documented, although some data suggest that an association is present.48,92,107 Tashiro reported that only 1% of TAO cases in Japan consisted of members of the same family.108 However, genes of the major histocompatibility complex, particularly HLA-A9 and HLA-B5, have been linked to TAO in a study from Liverpool, England.109 In Israel, a higher frequency of HLA-DR4 and a significantly lower frequency of HLA-DRW6 antigen were reported.96 In a Japanese population, haplotypes of various HLA groups were associated with Buerger’s disease.110,111 These haplotypes are rare among whites. Mehra and Jaini reported a strong positive association between HLA-DRB1*1501 in north Indian patients and TAO.112

Current concepts suggest that the arterial vasospasm of TAO may be caused by an interaction between smoking and several gene polymorphisms that reduce endogenous nitric oxide, an endothelium-derived vasodilator. Makita and colleagues demonstrated impaired peripheral endothelium-dependent vasorelaxation even in the non-diseased limbs of patients with TAO.113 Glueck and associates demonstrated that mutations associated with arterial vasospasm (5A/6A stromelysin-1, also called matrix metalloproteinase-3, homozygosity) were present in 7 of 21 (33%) TAO cases compared with 5 of 21 (24%) controls (risk ratio, 1.4; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.5 to 3.7).114

Hypercoagulability

Buerger’s disease is characterized by segmental inflammatory cell infiltration of the vessel wall and arterial or venous thrombotic occlusions.75,115 Hypercellular thrombus formation and preserved architecture of vessel walls are well established in TAO. However, most authorities have failed to identify a specific hypercoagulable state in patients with TAO17,116; others have shown one or more abnormalities (see Chapter 38). The role of thrombotic risk factors, such as the presence of factor V Leiden mutation and prothrombin gene mutation G20210A, remains controversial.116,117 One case-control study demonstrated a correlation between TAO and the presence of prothrombin 20210G/A mutation, suggesting that carriers of prothrombin 20210G/A mutation have an eightfold increased risk of TAO.118 Some authors suggest that hyperhomocysteinemia may have a role in the pathogenesis of Buerger’s disease.118–122 Stammler and associates reported increased homocysteine levels 4 hours after methionine loading (0.1 g/kg body weight) in 60% of patients with active TAO (9 of 15) but in none of the 5 age-matched healthy smokers or the 15 nonsmokers (P = .01).118 Mercie and colleagues detected hyperhomocysteinemia in three of their four TAO patients only after methionine loading.119 Increased platelet contractile force has been reported in several diseases associated with abnormal endothelial function and increased thrombotic risk, such as coronary artery disease and diabetes mellitus. Elevated platelet contractile force values were reported in two patients with TAO, despite the use of anticoagulation drugs and the suppression of adenosine diphosphate–mediated platelet aggregation.123 Whether high platelet contractile force plays a role in the pathogenesis of TAO or simply serves as a marker of enhanced platelet function, endothelial dysfunction, or both remains to be elucidated. Another study recently evaluated a panel of prothrombotic risk factors and demonstrated significantly higher median plasma activity of fibrinogen, factor VII, factor VIII, factor XI, and homocysteine in 37 patients with TAO compared with healthy controls.124

Oral Infection–Inflammatory Pathway

Historically, Buerger and then Allen and Brown proposed that infectious foci, including oral and throat infections, might serve as contributory factors in TAO.5 Another line of clinical evidence suggested an oral infection–inflammatory pathway as a possible etiologic link in TAO.125 Using a polymerase chain reaction method, the investigators demonstrated the DNA of oral bacteria (mainly Treponema denticola) in 12 of 14 arterial samples and in all oral samples (dental plaque and saliva) of patients with intermediate- or chronic-stage TAO.125 More recently, a higher prevalence of periodontitis and elevated immunoglobulin G titers against T. denticola, Porphyromonas gingivalis, and Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans were documented in patients with TAO.126

Pathology

The specific pathologic mechanisms in TAO are still unknown. Lesions occur in both the arterial and venous circulations.21 Earlier studies suggested TAO as a thrombotic disorder complicated by vasculitis, namely, transmural neutrophilic infiltration.24,53 Today, there are compelling reasons to believe that the primary event is the activation of antigen-presenting cells after endothelial cell damage induced by an unidentified antigen, possibly tobacco glycoproteins.59,79,96 Cellular and humoral immune reactions leading to thrombotic occlusion of vessels are restricted to the arterial intima, which defines TAO as an endarteritis.59,79 Intimal inflammation followed by T-cell infiltrations might result in early arterial occlusion, which is the pathognomonic finding in TAO.127

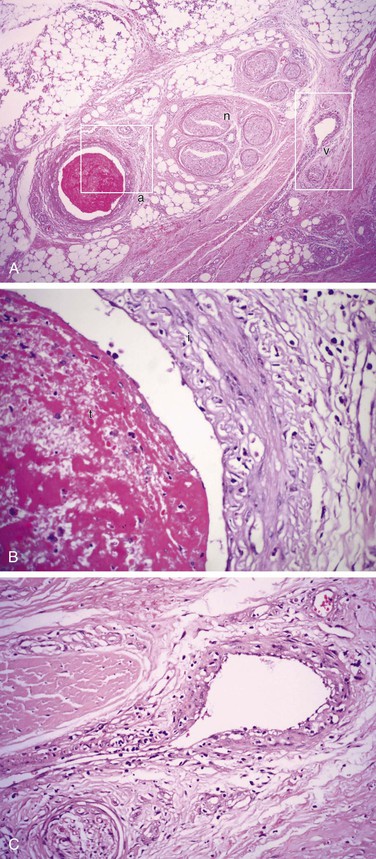

Progression of TAO is often divided into three categories (Box 79-2).24 In the acute phase, a panvasculitis within small and medium-sized (1- to 5-mm diameter) arteries and veins is observed. Primary features of acute-phase TAO are occlusive, highly cellular arterial thrombus; polymorphonuclear leukocytes with karyorrhexis; so-called microabscesses around the periphery of the thrombus; one or more multinucleated giant cells; marked inflammation involving all layers of the vessel wall; intimal thickening; and neutrophilic infiltration of the entire neurovascular bundle.10,28,46 However, most of the infiltrating cells are located in the intima.59 The intense inflammatory infiltration and cellular proliferation seen in acute lesions are distinctive, especially when veins are involved (Fig. 79-1). Multinucleated giant cells can be seen, but fibrinoid necrosis and granulomatous lesions are not observed.79

Figure 79-1 A, Typical subacute thrombotic occlusion of the right digital artery in a 37-year-old male smoker with Buerger’s disease (H&E, ×64). B, High-power view of area a in A demonstrating the digital artery with cellular arterial thrombus (t) and remarkable inflammation in the intima (i) (H&E, ×400). C, High-power view of area v in A demonstrating the adjacent digital vein with phlebitis (H&E, ×400). n, Nerve.

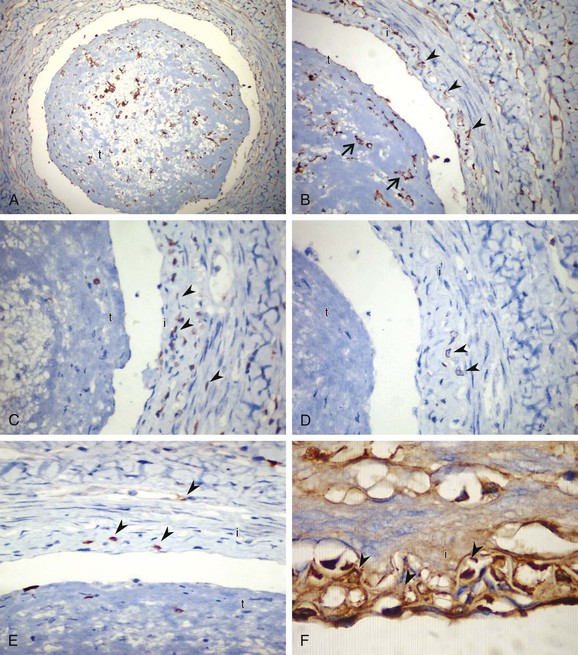

The acute phase is followed by an intermediate or subacute phase in which there is progressive organization of the occlusive thrombus, with partial recanalization and disappearance of the microabscesses.79 Both immunoglobulins and complement factors are deposited in a linear manner along the elastic lamina, which is characteristic of the acute or subacute phase.79 An inflammatory response, including CD3+ pan-T cells, CD4+ T helper-inducer cells, and CD20+ pan-B cells, to the internal elastic lamina of the affected vessels has been shown in detail (Fig. 79-2).79,127,128 Infiltrating cells in acute and subacute lesions are more abundant than in chronic lesions.59 In addition, CD68+ macrophages or S-100+ dendritic cells can be detected, especially in the intima, during the acute and subacute stages.59 Immunoglobulins G, A, and M and complement factors 3d and 4c are deposited in a linear manner along the inner aspect of the internal elastic lamina.79

Figure 79-2 A, Microphotograph of an acute-stage lesion with highly cellular thrombus (t) and inflammatory infiltration along the vessel wall with increased anti-CD68+ (clone: KP1) histiocytes. i, Intima. B, High-power view showing highly cellular thrombus (arrows) and abundant histiocytes in the intimal layer (arrowheads). C–E, Anti-CD3+ (rabbit polyclonal) stained T cells (C), anti-CD4+ (clone: 1F6) T-helper cells (D), and anti-CD8+ (clone: C8/144B) cytotoxic T cells (E) in the intimal layer (arrowheads; brown membrane staining, ×400). F, Deposition of immunoglobulin G (brown, arrowheads) within the interstitial intimal tissue (×600). Immunohistochemistry was performed with a Ventana iVIEW DAB detection system.

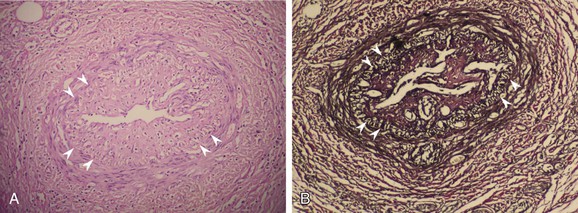

The chronic-phase or end-stage lesion is characterized by organization of the occlusive thrombus with extensive recanalization, prominent vascularization of the media, and perivascular fibrosis.24,28 In TAO, granulomas consisting of palisading epithelioid cells and giant cells may occur in arteries and in superficial and deep veins. They are localized not within the thrombus but in the muscular wall layer. Myointimal cell proliferation in the intima and thrombus may result in a continuous zone of fibrous tissue containing proliferating small blood vessels.115

Regardless of the pathologic stage, the internal elastic lamina and the architecture of the vascular walls are well preserved in TAO, in contrast to atherosclerosis and other types of systemic vasculitis (Fig. 79-3).16,24,28,79,129 Sato and colleagues recently investigated the mechanism of vessel wall preservation and intact internal elastic lamina in Buerger’s disease.130 They showed that plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 is strongly expressed along the internal elastic lamina of the affected arteries in patients with TAO.131 Furthermore, urokinase-type plasminogen activator (u-PA) and matrix metalloproteinase-3 were slightly positive in intima and media, whereas uPA and matrix metalloproteinase-3 were strongly positive in the media of patients with ASO.130 Regarding the plasma levels, however, u-PA, u-PA receptor, and u-PA/plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 complex were significantly greater in patients with TAO than in healthy controls, suggesting the activation of the u-PA system in Buerger’s disease.124

Figure 79-3 A, Microphotograph of a chronic-stage lesion of Buerger’s disease, with recanalized arterial thrombus and striking intimal thickening (H&E, ×200). The internal elastic lamina (arrowheads) and the architecture of the vascular wall are well preserved. B, The same vessel stained with elastic van Gieson (×200).

Inflammatory cell infiltration is found predominantly in the thrombi and the intima.79,128 Kobayashi and colleagues’ series of 33 specimens from nine patients revealed no calcification, atheromatous plaques, or hyaline degeneration in all vessel walls investigated.79 Kurata and associates suggested that the histologic findings, including onion-shaped recanalizing vessels in the occluded arteries, adventitial fibrosis without medial fibrosis, swelling of the endothelium of the vasa vasorum, and edema beneath the external elastic lamina, are characteristic of TAO and helpful in the differential diagnosis.128,131 They speculated that occlusion of the vasa vasorum may have an important role in the development of TAO.131 Lee and associates demonstrated that T-cell infiltration, vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 or inducible nitric oxide synthase expression, and TUNEL (terminal dUTP nick end labeling)–positive cells were located in the intima or adventitia in patients with Buerger’s disease.127

Clinical Presentation

TAO usually is manifested with distal extremity ischemia in a smoker before the age of 45 to 50 years.18,132 The median age at diagnosis is 34 years.17 Characteristically, distal extremity ischemia involves the feet, legs, hands, or arms (Fig. 79-4A and B). As the disease progresses, it may involve more proximal arteries.28 Frequently identified signs and symptoms of TAO are listed in Table 79-1. The most common symptoms are forefoot arch or lower calf claudication as a manifestation of infrapopliteal occlusive disease.28 Foot claudication is particularly characteristic.133 Claudication limited to the calf may occur, but this is unusual because the disease does not commonly progress proximally to involve either the above-knee popliteal or superficial femoral artery. Foot and arch claudication may be misattributed to orthopedic problems. Early symptoms may also include coldness, burning pain in the feet and hands, dependent rubor,134 cyanosis, migratory superficial thrombophlebitis,135 and Raynaud’s phenomenon25,30,47,136 (see Chapter 122).

Figure 79-4 A, Ischemic ulceration of the right second toe with a previously amputated great toe in a 42-year-old man who smoked three packs of cigarettes a day for 15 years. B, Necrosis of the ends of almost all fingers led to autoamputation in the same patient after continued smoking. C, One of the cardinal signs of thromboangiitis obliterans is superficial thrombophlebitis, seen here on the left leg of a 28-year-old smoker. Note the hairless skin distally. D, 34-year-old man presented with infected ischemic ulcer on the dorsum of the left foot involving skin, subcutaneous tissue and tendons. Note the previously amputated left great toe.

Patients with TAO commonly report cold sensitivity, and sensory findings may be one of the earliest manifestations. In the Cleveland Clinic series reported by Olin and colleagues, 69% of cases revealed sensory findings.25 Ischemic neuritis or superficial thrombophlebitis may also produce severe pain.137 Migratory superficial thrombophlebitis may occur as an early sign (Fig. 79-4C) and has been reported in 16% to 65% of TAO patients during the course of the disease135,138 (see Chapter 54). Ascending venography and histologic investigations suggest that 60% of the cases have venous involvement.139 On occasion, superficial thrombophlebitis may extend into the deep venous system. However, deep venous thrombosis in TAO is unusual.140 In the acute phase of the disease, involved vessels are tender and indurated and reflect the local inflammatory reaction. Biopsy of an acute superficial thrombophlebitis often demonstrates the typical histopathologic lesions of acute TAO (see Figs. 79-1 and 79-2).46

Trophic nail changes, ischemic ulcerations, and digital gangrene may be late findings (Fig. 79-4D).17,28,45,56,63,138 Almost all ulcers occur in patients between 20 and 50 years of age.141 Superinfection commonly develops, and the ischemic ulcerations progress toward necrosis and distal gangrene. At this stage, the pain is often excruciating. Ischemic ulcerations appear dry and irregular, with a pale base and various shapes.61,142 Joint manifestations, mainly transient, migratory episodes of arthritis, may occur in approximately 12.5% of patients in the preocclusive phase.143 Subungual splinter hemorrhages may be detected as an early sign.140,144 Coexisting psychological conditions are also common, primarily anxiety, depression, and amputation-related fears.145 No difference in clinical presentation in women compared with men has been detected.25,146

Multiple limb involvement is a common feature of TAO.16,28,33,147 In the series reported by Shionoya, two limbs were affected in 16% of patients, three limbs in 41%, and all four limbs in 43% of patients.147 The Intractable Vasculitis Syndromes Research Group of Japan reported isolated lower extremity involvement in 75%, only upper extremity involvement in 5%, and both upper and lower extremity involvement in 20% of patients with TAO (Table 79-2).148 Therefore, it is recommended that noninvasive imaging of all extremities be performed in patients with suspected Buerger’s disease.16,20 It is common to see angiographic abnormalities consistent with TAO in limbs that are not yet clinically involved.

Table 79-2

Distribution of Arterial Involvement in 825 Patients with Thromboangiitis Obliterans (1650 Upper and 1650 Lower Extremities)

| Lower extremity involvement only | 616 (74.7%) |

| Upper and lower extremity arteries | 167 (20.2%) |

| Upper extremity involvement only | 42 (5.1%) |

| LOWER EXTREMITY (n = 783) | |

| Anterior tibial artery | 683 (41.4%) |

| Posterior tibial artery | 667 (40.4%) |

| Dorsalis pedis artery | 349 (21.2%) |

| Peroneal artery | 304 (18.4%) |

| Popliteal artery | 301 (18.2%) |

| Digital arteries | 180 (10.9%) |

| Plantar arteries | 149 (9.0%) |

| Other | 296 (19.8%) |

| UPPER EXTREMITY (n = 209) | |

| Ulnar artery | 189 (11.5%) |

| Digital arteries | 133 (8.1%) |

| Radial artery | 115 (7.0%) |

| Superficial or deep palmar arch | 75 (4.5%) |

| Brachial artery | 13 (0.8%) |

| Other | 26 (1.6%) |

Modified from Sasaki S, et al: Distribution of arterial involvement in thromboangiitis obliterans (Buerger’s disease): results of a study conducted by the Intractable Vasculitis Syndromes Research Group in Japan. Surg Today 30:600-605, 2000.

Infrequently, TAO has been associated with visceral,149–169 cerebral,170–174 coronary,175–183 and internal thoracic artery161,162 involvement.177,178 Involvement of the cerebral vessels may result in progressive cognitive decline and migraine,184 transient ischemic attack, ischemic stroke, or schizophrenia-like symptoms.170–174 Coronary artery involvement may result in myocardial ischemia or infarction.175–183 Visceral vessel involvement may be manifested as abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, fever, diarrhea, melena, weight loss, and anorexia and result in ileus, ischemic colitis, mesenteric infarction, intestinal perforation, or liver hypoxia.150–155,159,161,166–168 There have also been rare reports of multiple-organ involvement in TAO.185,186 Involved vascular beds exhibit pathologic characteristics similar to vessels in the extremities.

Even rarer are instances of TAO in saphenous vein arterial grafts,187 temporal arteries,188 ophthalmic circulation,189–191 and intrarenal arterial branches192 of smokers. Also uncommon but reported is the occurrence of TAO in pudendal,193,194 testicular, and spermatic arteries and veins, as was originally described by Buerger.4 Rare cases of nephropathy as a result of mesangial immunoglobulin A deposition,195 cutaneous manifestations presenting as painful nodular erythema with livedo reticularis,196 and avascular necrosis of femoral heads197 have also been reported. TAO in unusual locations should be diagnosed only when the histopathologic findings are classic for the acute-phase lesion and the clinical presentation is consistent with the diagnosis of Buerger’s disease.20

A complete vascular examination is critical for the diagnosis. Physical examination reveals involvement of small and medium-sized arteries, with normal brachial and femoral pulses. The radial, ulnar, dorsalis pedis, or posterior tibial pulse may be absent. Digital arteries may be occluded. An abnormal Allen’s test result suggesting ulnar artery occlusion in a young smoker with lower extremity ulcerations is highly suggestive of TAO. Abnormal Allen’s test results occurred in 63% of cases in the Cleveland Clinic series.25 Superficial phlebitis may be another clue to the diagnosis. Calculation of the ankle-brachial index or toe-brachial index at rest and after exercise is recommended as the initial screening test. Seasonal variation, with exacerbation of TAO occurring more frequently in the winter, has been reported198,199; this may be attributed to cold weather and the stimulation of vasospasm and Raynaud’s phenomenon.198

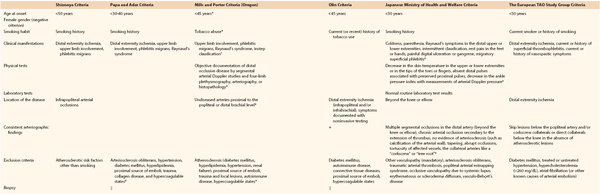

Diagnostic Evaluation

A century after its first description, the major clinical challenge in TAO is the absence of universally accepted diagnostic criteria.14,16,200–202 The traditional diagnosis of TAO is based on Shionoya’s criteria, with all five elements required: (1) smoking history, (2) onset before the age of 50 years, (3) infrapopliteal arterial occlusive lesions, (4) either upper limb involvement or phlebitis migrans, and (5) absence of atherosclerotic risk factors other than smoking.14 In 1992, Papa and Adar proposed various clinical, angiographic, histopathologic, and exclusionary criteria, and in a second report they proposed a point-based scoring system to improve the diagnostic certainty.203 Mills and Porter developed more rigid major and minor supportive criteria based on the analysis of a cohort of patients in Oregon.204 The diagnostic classification schemes are summarized in Table 79-3. All investigators accepted the exclusion of atherosclerotic risk factors other than smoking as part of the diagnostic algorithm. Therefore, TAO is a clinical diagnosis, and the diagnosis requires investigations aimed at exclusion of other possible diagnoses. A biopsy is rarely needed unless the patient presents with unusual characteristics, such as large-artery involvement or age older than 45 years.16 Kroger suggested that the exclusion of arteriosclerosis should be considered only if TAO is manifested in young patients aged 20 to 30 years.202

Table 79-3

Comparison of Suggested Diagnostic Criteria for Thromboangiitis Obliterans

* Major criteria.

† Minor criteria support the diagnosis.

‡ Mandatory; at least one or two.

§ Adar et al suggested the establishment of a consensus on hypercoagulable states.

‖ Indicated only for patients with an unusual characteristic not well matched with Buerger’s disease.

Data from references 16, 17, 20, 25, 27, 138, 148, 201, 203, 233.

Noninvasive Testing

Four-limb segmental arterial pressure measurements and pulse volume recordings are usually normal above the knee and markedly reduced distally.74 Abnormal digital plethysmographic patterns in both lower and upper extremities would objectively document distal occlusive disease in a patient meeting the clinical criteria for TAO.17,49,73,205,206 Calcification of the involved arterial wall is almost always absent on plain radiography.21 Arterial duplex scanning is used not only to exclude proximal atherosclerotic lesions and to demonstrate distal arterial occlusive disease (see Chapter 16) but also to visualize and functionally evaluate the corkscrew collaterals (“snake” sign and “dot” sign) by continuous wave Doppler ultrasound (Fig. 79-5).207,208 In a study from Poland, Doppler spectral waveform analysis in 40 TAO patients and 40 healthy subjects revealed a reduction of reversed diastolic flow amplitude, with no significant decrease in peak systolic amplitude, in patients with TAO.209 The authors concluded that decreased vascular resistance might develop as a result of increased collateral blood flow and low-resistance cutaneous arteries; thus, resistance index can be a useful Doppler parameter in the early diagnosis of TAO and probably in monitoring of disease progression. Another study confirmed that flow-mediated vasodilatation was augmented in a corkscrew collateral artery but impaired in a native artery in patients with TAO.210 These findings indicate selective impairment of vascular endothelium but not of smooth muscle cells in native arteries in patients with Buerger’s disease.210 Transcutaneous oxygen pressure can be used to confirm the ankle-toe gradient and the severity of ischemia.

Figure 79-5 Color-flow Doppler studies demonstrating triphasic flow within the right (A) and left (B) anterior tibial arteries, monophasic flow within the left dorsalis pedis artery (C), and the “dot” sign as a result of continuous flow within corkscrew collaterals at the toe level (D and E).

Emboli as a cause of distal ischemia should be ruled out as the signs and symptoms of embolic occlusions can mimic those of TAO. Cardiac investigations, including electrocardiography, rhythm monitoring, and echocardiography, are recommended to rule out cardiac and thoracic aortic sources of emboli to the involved extremity (see Chapter 164). Abdominal ultrasonography may be considered to rule out a proximal source of emboli from an abdominal aortic aneurysm or atherosclerotic aorta. Furthermore, ischemic ulcerations with signs and symptoms of secondary infection should be evaluated by conventional radiography and magnetic resonance imaging to determine the presence of osteomyelitis.211

Angiography

Digital subtraction angiography plays an important role in both supporting the diagnosis of TAO and ruling out other causes of ischemia (see Chapter 19). Arteriographic findings in TAO may be suggestive but not pathognomonic. Thus, this method is not a “gold standard” for diagnosis. Segmental occlusive lesions (diseased arteries interspersed with normal-appearing arteries), more severe disease distally, involvement of digital arteries,49 normal proximal arteries without evidence of atherosclerosis, and collateralization around areas of occlusion with corkscrew-shaped collaterals (Martorell’s sign, also described as “tree root” or “spider leg” collaterals) are the common features of TAO (Fig. 79-6).212,213 The infrapopliteal and infrabrachial arteries are the most common sites of occlusion. Small corkscrew patterns are associated with a higher prevalence of ischemic ulcers compared with large corkscrew collaterals.214 Although corkscrew collaterals, which represent widened vasa vasorum, suggest TAO to many clinicians,212 this finding alone is not pathognomonic. Corkscrew collaterals can be seen in connective tissue diseases such as scleroderma, CREST syndrome (calcinosis, Raynaud’s phenomenon, esophageal disease, sclerodactyly, telangiectasia), systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid vasculitis, and antiphospholipid antibody syndrome.16 Furthermore, cocaine, amphetamine, or cannabis addiction can cause Buerger’s-like clinical and angiographic signs.39,82–85,140,215 Angiographic features that support a diagnosis of TAO are listed in Box 79-3. A study from Japan determined the distribution of arterial involvement in TAO on the basis of a nationwide survey in 1993 by the Intractable Vasculitis Syndromes Research Group (see Table 79-2).149

Figure 79-6 A and B, Abrupt right tibial vessel occlusion with corkscrew collaterals (arrows) in a 34-year-old man detected with 64-slice multidetector computed tomographic angiography.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree