Chapter 44 Thromboangiitis Obliterans (Buerger’s Disease)

Thromboangiitis obliterans (TAO) describes a segmental nonatherosclerotic inflammatory disorder that primarily involves the small and medium arteries, veins, and nerves of the extremities.1–3 Although TAO was initially thought to be a disease confined exclusively to men, recent epidemiological studies demonstrate a growing population of women with the disorder. Also known as Buerger’s disease, TAO has an extremely strong pathophysiological relationship with tobacco use, usually in the form of heavy cigarette smoking.

In 1879, von Winiwarter provided the first description of a patient with TAO. He presented the case of a 57-year-old man who had reported pain in his feet for 12 years. Histopathological examination of an amputation specimen from this patient demonstrated intimal proliferation, luminal thrombosis, and fibrosis; von Winiwarter hypothesized that the endarteritis and endophlebitis observed were distinct from atherosclerosis.4 In his landmark paper 29 years later,5 Leo Buerger published a detailed report of the pathological findings of 11 amputated limbs from patients with the disease and coined the term thromboangiitis obliterans to describe the characteristic observations of endarteritis and endophlebitis. Similar to von Winiwarter, Buerger made a point to distinguish the clinical and pathological findings of TAO from those of atherosclerosis.

In 1928, Allen and Brown described the clinical and pathological characteristics of 200 cases of TAO seen at the Mayo Clinic from 1922 to 1926.6 The majority of cases occurred among Jewish men, and all patients were heavy smokers. The pathological findings in this report were virtually identical to those described in Buerger’s original paper.

Epidemiology

Although it is observed worldwide, TAO is more prevalent in the Middle East and Far East than North America and Western Europe.7,8 Prior to the late 1960s, overdiagnosis of TAO was frequent. Of 205 cases originally diagnosed as TAO at Mount Sinai Hospital from 1933 to 1963, only 33 were later believed to be compatible with the diagnosis, 28 were considered questionable, and 144 were determined incorrect.9

Adoption of stricter diagnostic criteria and a reduction in tobacco use have caused the reported number of new patients diagnosed with TAO in the United States and Europe to decline. Overall incidence of TAO is higher in regions of the world where consumption of tobacco is greater. At the Mayo Clinic over a 40-year period, the prevalence rate of patients with the diagnosis of TAO has decreased from 104 per 100,000 patient registrations in 1947 to 13 per 100,000 patient registrations in 1986.7 The prevalence rate of TAO in patients with peripheral artery disease (PAD) varies across Europe and Asia: 1% to 3% in Switzerland, 0.5% to 5% in West Germany, 1.2% to 5.6% in France, 4% in Belgium, 0.5% in Italy, 0.25% in the United Kingdom, 3.3% in Poland, 6.7% in East Germany, 11.5% in Czechoslovakia, 39% in Yugoslavia, 80% in Israel (among Ashkenazi Jews), 45% to 53% in India, and 16% to 66% in Japan and Korea.10 In Asia, a greater proportion of patients with limb ischemia has been attributed to TAO than in the United States and Europe.

Overall incidence of TAO also appears to be declining in South Asia and Japan.11,12 During the 1990s, the ratio of new patients with TAO to new patients with atherosclerotic PAD was reported to be 1:3 in a vascular outpatient clinic in Japan.13 Since 2000, the ratio has declined to 1:10.13

Thromboangiitis obliterans has been associated with manual labor and lower socioeconomic status in some series. In particular areas of Southeast Asia, including India, TAO has been associated with lower socioeconomic class and smoking unrefined homemade tobacco cigarettes called bidi. In a study of 28 cases of TAO from Korea, 23 patients were farmers or manual laborers and belonged to the lowest socioeconomic class.14 In another analysis of 106 patients with TAO in Java, Indonesia, the majority of patients were from the lowest socioeconomic class.15 However, in a study of 8858 Japanese patients with the disease, there was no significantly greater prevalence among manual laborers.16

Although it has been considered a disease of young men, TAO also occurs in women. Reported incidence was less than 2% in the majority of published case series before 1970. More recent studies have demonstrated a much higher prevalence, ranging from 11% to 23%.17–20 The increasing prevalence of TAO among women has been attributed to rising consumption of tobacco products.

Etiology and Pathogenesis

Tobacco

Exposure to tobacco is critical to initiation, maintenance, and progression of TAO. Although smoking tobacco is by far the most frequent precipitating factor, chewing tobacco and using snuff21 or marijuana have also been implicated in its development.22,23 The association between heavy tobacco use and TAO is so strong, it is typically considered a sine qua non for the diagnosis.17,24 Patients with TAO have higher tobacco consumption and carboxyhemoglobin levels than those with atherosclerotic vascular disease or healthy controls.25 It has been hypothesized that some patients develop an immunological reaction to a constituent of tobacco that triggers small-vessel occlusive disease.26,27 Because only a small proportion of smokers worldwide eventually develop TAO, other factors are believed to play a contributory role in disease pathogenesis.

As noted earlier, in South Asia, a large proportion of patients diagnosed with TAO belong to the lowest socioeconomic class and smoke bidi. Bidi smoking is believed to account for the higher incidence of TAO in the Indian population. A case-control study from Bangladesh reported that 35% of patients with TAO were cigarette smokers and 65% were bidi smokers, compared with 69.9% and 30.1%, respectively, of controls.28 After adjusting for confounding factors and using 10-per-day smoking frequency as a reference, the study found that smoking 11 to 20 bidi per day was associated with a seven fold increased risk of developing TAO, and smoking over 20 bidi per day led to a 35-fold increased risk. The authors concluded that bidi smoking carried greater risk than cigarette smoking for consequent TAO.28

In addition to its role in disease initiation, tobacco use is a critical factor in disease progression and continued symptoms associated with TAO.2 Although second-hand or passive smoking has not been associated with TAO onset, it may play an important role in continuation of the disease process. In a study of 40 patients with TAO, cotinine, the major metabolite of nicotine, was used as a measure of exposure to tobacco smoke. Urinary cotinine levels were measured to classify them as smokers (cotinine levels >50 ng/mg creatinine), passive smokers (cotinine levels 10-50 ng/mg creatinine), and nonsmokers who did not experience noticeable passive smoking (cotinine levels <10 ng/mg creatinine).29 Using these criteria, 10 patients were classified as smokers, 9 as passive smokers, and 21 as nonsmokers. Seven of the 10 smokers, none of the 9 passive smokers, and 4 of the 21 nonsmokers experienced disease exacerbation. Of the four nonsmokers who experienced disease exacerbation, three had continued to smoke and one had been exposed to second-hand tobacco smoke in the workplace at the time of relapse. Among active smokers, the seven whose conditions had worsened showed significantly higher urinary cotinine levels than the three remaining patients who remained in remission.

Genetic Predisposition

Several studies have suggested there may be a genetic predisposition to developing TAO. Although there appears to be an association between certain human lymphocyte antigen (HLA) haplotypes and development of TAO, no consistent pattern has been identified across patient populations. In the United Kingdom, HLA-A9 and HLA-B5 are particularly prevalent in patients with TAO.30 In a U.S. study, HLA testing was performed in 11 patients with TAO, and no specific pattern could be identified.18 Lack of consistency in HLA haplotype predominance among various populations with TAO is likely due to genetic diversity and methodological differences in each of the studies.31

Polymorphisms of CD14, a main receptor for bacterial lipopolysaccharide, (37.4% vs. 24.2%; P = 0.008; odds ratio [OR] = 1.87; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.18-2.97), HLA-DRB1 (34.4% vs. 13.2%; P < 0.001; OR = 3.44; 95% CI, 2.06-5.73), and HLA-DPB1 (79.4% vs. 55.1%; P < 0.001; OR = 3.14; 95% CI, 1.93-5.11) have been observed to have a significantly higher frequency in patients with TAO than in controls.32 Stratification analyses of these polymorphisms suggested synergistic roles with ORs that ranged from 4.72 to 12.57 in individuals carrying any two of these three markers. These data suggest that susceptibility to TAO may be controlled in part by genes involved in innate and adaptive immunity.

In a study comparing 21 TAO patients with healthy age-, gender-, and race-matched controls, frequency of mutations associated with arterial vasospasm (stromelysin-1 5A/6A, endothelial nitric oxide synthase [eNOS] T-786 C) was evaluated.33 Homozygosity for 5A/6A stromelysin-1 was present in 7 of 21 (33%) TAO cases, compared with 5 of 21 (24%) controls (risk ratio 1.4; 95% CI, 0.5-3.7). Homozygosity for eNOS T-786 C was present in 3 of 21 (14%) TAO cases, compared with 1 of 21 (5%) controls (risk ratio 3.0; 95% CI, 0.3-26.6).

In another recent study, eNOS 894 G→T and endothelin-1 (ET-1) 8000 T→C polymorphisms were assessed to determine whether either played a role in development of TAO.34 Investigators found that the T allele of the eNOS 894 G→T polymorphism was protective against TAO.

Hypercoagulable States

The role of hypercoagulable states in TAO pathogenesis remains unclear; studies have failed to demonstrate a consistent pattern of association. In a comparison of patients with TAO and healthy controls, levels of urokinase-plasminogen activator (uPA) were twofold higher, and free plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1) were 40% lower, in patients with the disease.35 During venous occlusion, tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) antigen concentrations increased to a greater extent in controls while PAI-1 levels were lower in patients with TAO. Patients with TAO also appear to have an enhanced platelet response to serotonin36 and higher platelet contractile force.37

In one case-control study, the frequencies of factor V Leiden and prothrombin gene 20210A mutations were similar in patients with TAO and healthy subjects.38 However, in another case-control study, OR for the prothrombin 20210 A allele compared with the G allele was 7.98 (95% CI, 2.45-25.93) in patients with TAO.39 Elevated plasma homocysteine levels have been reported in patients with TAO and may be associated with a higher amputation rate.40

Increased levels of anticardiolipin antibodies have been reported in patients with TAO.40–42 In one study, anticardiolipin antibodies were measured in 47 patients with TAO, 48 patients with premature atherosclerosis, and 48 otherwise healthy individuals.42 Prevalence of anticardiolipin antibodies was significantly higher in patients with TAO (36%) compared with those with premature atherosclerosis (8%; P = 0.01) and healthy controls (2%; P < 0.001). Compared with those without detectable autoantibodies, patients with TAO and elevated anticardiolipin antibody titers were younger at age of onset and had increased rates of major amputation. A smaller study, however, did not demonstrate increased amputation rates in TAO patients with elevated anticardiolipin antibodies.40

Immunological Mechanisms

Abnormalities in immunoreactivity are believed to play a critical role in the inflammatory process that characterizes TAO. In a study of 39 patients with TAO, cellular and humoral immune responses to native human collagen type I and type III were evaluated.43 Cell-mediated sensitivity to these collagens as measured by an antigen-sensitive thymidine incorporation assay was significantly higher in patients with TAO than in patients with atherosclerosis or in healthy male controls. Lymphocytes from 77% of the patients with TAO demonstrated cellular sensitivity to type I or type III collagens or both. In 17 of 39 serum samples (44%) from the patients with TAO, a low but significant level of anticollagen antibody activity was detected, whereas no antibody activity was observed in serum samples from controls. Circulating immune complexes found in peripheral arteries of patients with TAO provide further evidence for an immunological basis for this disease.44,45

In a study of nine patients with TAO, immunohistochemical analysis was performed on 33 specimens.46 Architecture of blood vessel walls was well preserved regardless of the stage of disease, but cell infiltration involving the thrombus and intima was observed. Among infiltrating cells, CD3+ T cells greatly outnumbered CD20+ B cells, and CD68+ macrophages or S-100+ dendritic cells were detected in the intima during acute and subacute phases. Deposits of immunoglobulins (Ig)G, IgA, and IgM and complement factors 3d and 4c were noted along the internal elastic lamina. These data indicate that TAO represents an endarteritis characterized by both T cell– (cellular) and B cell–mediated (humoral) immunity in association with activation of antigen-presenting cells in the intima.

Immunohistochemical and TUNEL (terminal dUTP nick end labeling) studies were conducted on arterial walls obtained from eight patients with TAO to phenotype infiltrating cells with CD4+ (helper T cell), CD8+ (cytotoxic T cell), CD56 (natural killer cell), and CD68 (macrophage) to (1) identify cell activation with vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1) and inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS), (2) determine the presence of cell death with TUNEL analysis, and (3) detect inflammatory cytokines with reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR).47 T cells were identified mainly in the thrombus, intima, and adventitia. Among infiltrating cells, CD4+ T cells greatly outnumbered CD8+ cells. VCAM-1 and iNOS were expressed in endothelial cells (ECs) around the intima in patent segments or in vaso vasorum in occluded segments. These findings suggest that a T cell–mediated immune response may play an important role in development of TAO.

An immunohistochemistry study compared 58 amputated lower extremities from patients with TAO to 5 autopsy controls.48 In patients with a definite diagnosis of TAO, as determined by clinical criteria, linear arrangement of macrophages, B lymphocytes, and T lymphocytes along vascular elastic fibers was found to be a predictable and specific inflammatory response to the internal elastic lamina of affected vessels. This finding indicates that elastic fibers are important immunogens in TAO pathogenesis.

Endothelial Dysfunction

Abnormalities of endothelial function also appear to contribute to TAO pathogenesis. Although various autoantibodies commonly observed in vasculitides are typically absent, elevations in antiendothelial cell antibody titers have been documented in patients with active TAO.49 In one study, seven patients with active TAO had antiendothelial cell antibody titers of 1857 ± 450 arbitrary units (AU), compared with 461 ± 41 AU in 21 patients in remission (P < 0.01) and 126 ± 15 AU in 30 control subjects (P < 0.001).49 If these findings can be confirmed, measurement of antiendothelial cell antibody titers may serve as a useful tool in following disease activity.

Patients with TAO also demonstrate impairment of endothelium-dependent vasodilation in the peripheral vasculature. Changes in forearm blood flow induced by the endothelium-dependent vasodilator acetylcholine, the endothelium-independent vasodilator sodium nitroprusside, and occlusion-induced reactive hyperemia were measured plethysmographically in the nondiseased limb in eight patients with TAO and in eight healthy controls matched for age and smoking status.50 The increase in forearm blood flow response to intraarterial acetylcholine infusion was diminished in patients with TAO compared with healthy controls (22.9 ± 2.9 vs. 14.1 ± 2.8 mL/min per dL of tissue volume; P < 0.01). In contrast, there was no significant difference in the increase in forearm blood flow response to sodium nitroprusside infusion and reactive hyperemia between the two study groups. These data suggest that peripheral endothelium-dependent vasodilation is impaired even in the nondiseased limbs of patients with TAO.

In a study designed to evaluate the role of circulating progenitor cells in endothelial function in patients with TAO and atherosclerosis obliterans, investigators measured flow-mediated vasodilation, nitroglycerin-induced vasodilation, and circulating progenitor cells in 30 patients with TAO, 30 age- and sex-matched healthy subjects, and 40 patients with atherosclerosis obliterans.51 Flow-mediated vasodilation was decreased in both the TAO group and atherosclerosis obliterans group compared with controls (6.6% ± 2.7%, 5.7% ± 3.3% vs. 9.5 ± 3.1%, P < 0.0001, respectively). However, there was no significant difference in flow-mediated vasodilation between the TAO group and atherosclerosis obliterans group. Nitroglycerin-induced vasodilation was similar in the three groups. The number and migration of circulating progenitor cells were similar in the TAO group and control group, but were significantly decreased in the atherosclerosis obliterans group. There was a significant relationship between the number and migration of circulating progenitor cells and flow-mediated vasodilation (r = 0.43 and r = 0.40, P < 0.0001, respectively). Flow-mediated vasodilation was impaired in patients with TAO and patients with atherosclerosis obliterans compared with control subjects, but the number and function of circulating progenitor cells were not decreased in patients with TAO.

In a study of surgical biopsies obtained from femoral and iliac arteries of patients with TAO, expression of intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1), VCAM-1, and E-selectin was increased on endothelial and inflammatory cells in the thickened intima.52 Immunohistochemistry demonstrated contacts between mononuclear cells and morphologically activated ECs expressing ICAM-1 and E-selectin. These findings provide evidence for EC activation, tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α secretion by tissue-infiltrating inflammatory cells, ICAM-1, VCAM-1 and E-selectin expression on ECs, and leukocyte adhesion in TAO.

Infection

Chronic anaerobic periodontal infection may represent an additional risk factor for development of TAO.53 Nearly two thirds of patients with TAO have severe periodontal disease. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis demonstrated deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) fragments from anaerobic bacteria, in particular Treponema denticola, in both arterial lesions and oral cavities of patients with TAO, but not in arterial samples from healthy control subjects. However, the higher prevalence of periodontal infection in TAO may simply be a marker of lower socioeconomic status in patients who develop the disease, rather than a pathogenic correlate.

Pathology

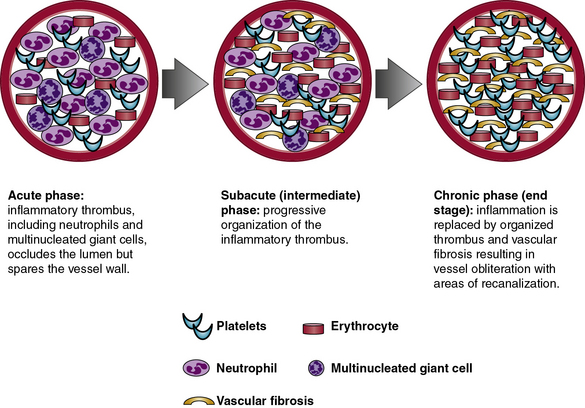

Pathologically, TAO is distinguished by inflammatory thrombus that affects small- and medium-sized arteries and veins. Histopathology of involved blood vessels varies according to the stage at which the tissue sample is obtained. Thromboangiitis obliterans involves three phases: acute, subacute, and chronic (Fig. 44-1). Histopathology is most likely to be diagnostic of TAO in samples obtained during the acute phase of the disease. As the disease progresses from the subacute to chronic phases, the histopathology of TAO becomes virtually indistinguishable from other obstructive vascular diseases that result in fibrosis of the blood vessels in their end stage. Because the histological appearance can vary from patient to patient and depends upon the stage of the disease, a pathological diagnosis of TAO may be challenging in some cases.54 Furthermore, pathological diagnosis may be inconclusive if only amputated specimens or occluded arteries and veins are examined. Subacute and chronic phase lesions have far fewer characteristic features and therefore are rarely diagnostic for TAO.

Acute Phase

The acute phase of TAO consists of an occlusive, highly cellular, inflammatory thrombus. Polymorphonuclear neutrophils, microabscesses, and multinucleated giant cells are often present around the periphery of the thrombus (Fig. 44-2). Presence of multinucleated giant cells is characteristic of but not specific for TAO.55

Inflammatory thrombus is observed with greatest frequency in biopsies of areas demonstrating acute superficial thrombophlebitis taken from patients with TAO. It is unclear whether the vascular lesions of TAO are primarily thrombotic or inflammatory, but the pattern of intense inflammatory cell infiltration and cellular proliferation observed in the acute phase of the disease is particularly distinctive. Acute phlebitis without thrombosis, acute phlebitis with thrombosis, and acute phlebitis with thrombus containing microabscesses and giant cells may coexist in different segments of the same affected vein if it is biopsied at an early stage. These lesions correspond with the clinical finding of thrombophlebitis migrans.56

Subacute (Intermediate) Phase

During the subacute or intermediate phase, progressive organization of the inflammatory thrombus takes place in affected arteries and veins. Although some degree of inflammatory infiltrate remains within the thrombus, the vessel wall is generally spared. Partial recanalization of the vessel and disappearance of microabscesses may also be observed in the subacute phase.46

Immunohistochemical Features

Studies focusing on immunohistochemistry have provided limited understanding of the role of the cytoskeleton and other cellular elements in TAO.44–48,52,57 Soon after the inflammatory thrombus has occluded the vessel lumen, spindle cells migrate from the media through fenestrations in the internal elastic lamina into the intima to populate the periphery of the thrombus. These spindle cells express vimentin and α1-actin and originate from smooth muscle cells (SMCs) of the media. Capillaries appear along thrombus margins. Endothelial cells express factor VIII–related antigen and Ulex europaeus agglutinin.

Clinical Presentation

The typical patient with TAO is a young man with a history of heavy tobacco smoking who presents with onset of ischemic symptoms of the extremities before age 45 years. However, patients should be questioned about chewing tobacco as well as snuff and marijuana use, especially if they deny smoking and present with a history compatible with TAO. Ischemic symptoms result from stenosis or occlusion of the distal small arteries and veins. Thromboangiitis obliterans frequently progresses proximally and involves multiple limbs. Large-artery involvement is atypical and rarely occurs in the absence of small-vessel occlusive disease.58 The most common symptoms result from arterial occlusive disease, secondary vasospasm, and superficial thrombophlebitis (Table 44-1).

Table 44-1 Presenting Symptoms and Signs in 112 patients with Thromboangiitis Obliterans Evaluated at Cleveland Clinic Between 1970 and 1987*

| Clinical Finding | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Intermittent claudication | 70 (63) |

| Rest pain | 91 (81) |

| Ischemic ulcerations: Upper extremity Lower extremity Both | 85 (76) 24 (28) 39 (46) 22 (26) |

| Thrombophlebitis | 43 (38) |

| Raynaud phenomenon | 49 (44) |

| Sensory findings | 77 (69) |

| Abnormal Allen test | 71 (63) |

* Data from Olin JW, Young JR, Graor RA, et al: The changing clinical spectrum of thromboangiitis obliterans (Buerger’s disease). Circulation 82:3–8, 1990.

Arterial Occlusive Disease

Arterial occlusive disease due to TAO most often presents as intermittent claudication of the feet, legs, hands, or arms. In a study of 112 patients with TAO evaluated at the Cleveland Clinic from 1970 to 1987, intermittent claudication occurred in 70 patients (63%).17 In a retrospective study of 344 patients treated surgically for TAO in Turkey, major complaints included foot coldness in 312 (90.6%) patients, color changes in 290 (84.3%), rest pain in 160 (46.5%), claudication in 166 (48.2%), and necrotic ulcers in 185 (53.1%).59 Foot or arch claudication may be a presenting symptom and is frequently attributed to an orthopedic problem, resulting in diagnostic delay. As lower-extremity disease progresses proximally, patients with TAO may report classic calf claudication.

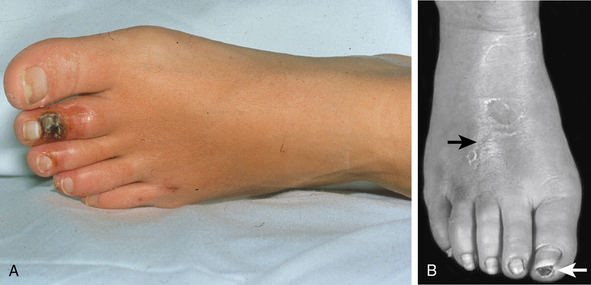

Symptoms and signs of critical limb ischemia, including rest pain, ulcerations, and digital gangrene, occur with advanced arterial occlusive disease. At the time of presentation, 76% of patients have ischemic ulcerations (Fig. 44-3A and Fig. 44-4).17 With early recognition of symptoms and signs of TAO, many patients can be identified and treated before critical limb ischemia develops.

Although only one limb may be affected clinically, arterial occlusive disease always involves two or more extremities on angiographic evaluation. In one series of patients with TAO, two limbs were affected in 16% of patients, three limbs in 41%, and all four limbs in 43%.60 The Intractable Vasculitis Syndromes Research Group of Japan reported isolated lower limb involvement in 75%, isolated upper limb involvement in 5%, and both upper and lower limb involvement in 20% of patients with TAO.61

Raynaud Phenomenon

A common complaint in TAO, cold sensitivity may represent one of the earliest manifestations of the disease. Indeed, presentations of TAO appear to be more common in the winter.62 Cold sensitivity likely results from ischemia or markedly increased muscle sympathetic nerve activity, which has been demonstrated in TAO patients compared with controls.63 Raynaud phenomenon is present in over 40% of patients with TAO and may be asymmetrical.2 The extremities, particularly the digits, may be characterized by either rubor or cyanosis. This discoloration has been termed Buerger’s color.64

Superficial Thrombophlebitis

Although it may also be observed in Behçet disease, superficial thrombophlebitis differentiates TAO from other vasculitides and atherosclerotic vascular disease (see Fig. 44-3B). Superficial thrombophlebitis occurs in approximately 40% of patients with TAO.17 Superficial thrombophlebitis may predate the onset of ischemic symptoms caused by arterial occlusive disease56 and may parallel disease activity.65 Some patients may describe a migratory pattern of tender nodules that follow a venous distribution (thrombophlebitis migrans).56

Neurological Findings

Sensory abnormalities are common in TAO and were observed in up to 70% of cases in a series from the Cleveland Clinic.17 Sensory findings are most likely due to ischemic neuropathy, a late finding in the course of TAO. Sensory findings may also be due to primary involvement of the nerves themselves, since earlier studies have suggested that inflammatory cell infiltrate may surround the nerves.5

Unusual Presentations

Thromboangiitis obliterans of large elastic arteries such as the pulmonary66 and iliac arteries58 has been rarely documented. Visceral involvement may present as abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, melena, hematochezia, weight loss, and anorexia and result in mesenteric ischemia or infarction.67–72 Cerebrovascular involvement may manifest as transient ischemic attack (TIA), ischemic stroke, and psychotic disorders.73–77

Coronary artery involvement may present as myocardial ischemia or infarction.78–82 Thromboangiitis obliterans affecting the intrarenal arterial branches has been reported.83 Rarely, TAO may involve the pelvic vessels, including the pudendal arteries and veins, resulting in erectile dysfunction.84 Thromboangiitis obliterans involving the temporal and ophthalmic arteries may mimic giant cell arteritis (GCA).85,86

Involvement of saphenous vein bypass grafts in patients with TAO is a truly rare occurrence.87

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree